Jock Macdonald was a trailblazer in Canadian art from the 1930s to 1960. He was the first painter to exhibit abstract art in Vancouver, and throughout his life he championed Canadian avant-garde artists at home and abroad. His career path reflected the times: despite his commitment to his artistic practice, he earned his living as a teacher, becoming a mentor to several generations of artists. As a strong supporter of artists’ organizations, he was a founding member of both the Canadian Group of Painters and Painters Eleven, and was instrumental in establishing the Calgary Group.

Early Years

James Williamson Galloway Macdonald (1897–1960) was born in Thurso, Scotland—the most northerly town on the British mainland. Family members were noted for their achievements in architecture and the arts. His twin sister, Isobel, an accomplished musician, remembered that the young Jock, as he was called, was always drawing. After he graduated from high school, he decided to follow his father’s career path as an architect and began apprenticing as a draftsman in Edinburgh. The First World War intervened and, like so many of his generation, Macdonald enlisted, serving as a Lewis gunner in the Fourteenth Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. He was wounded in France and spent a year convalescing in hospital before he was posted to Ireland.

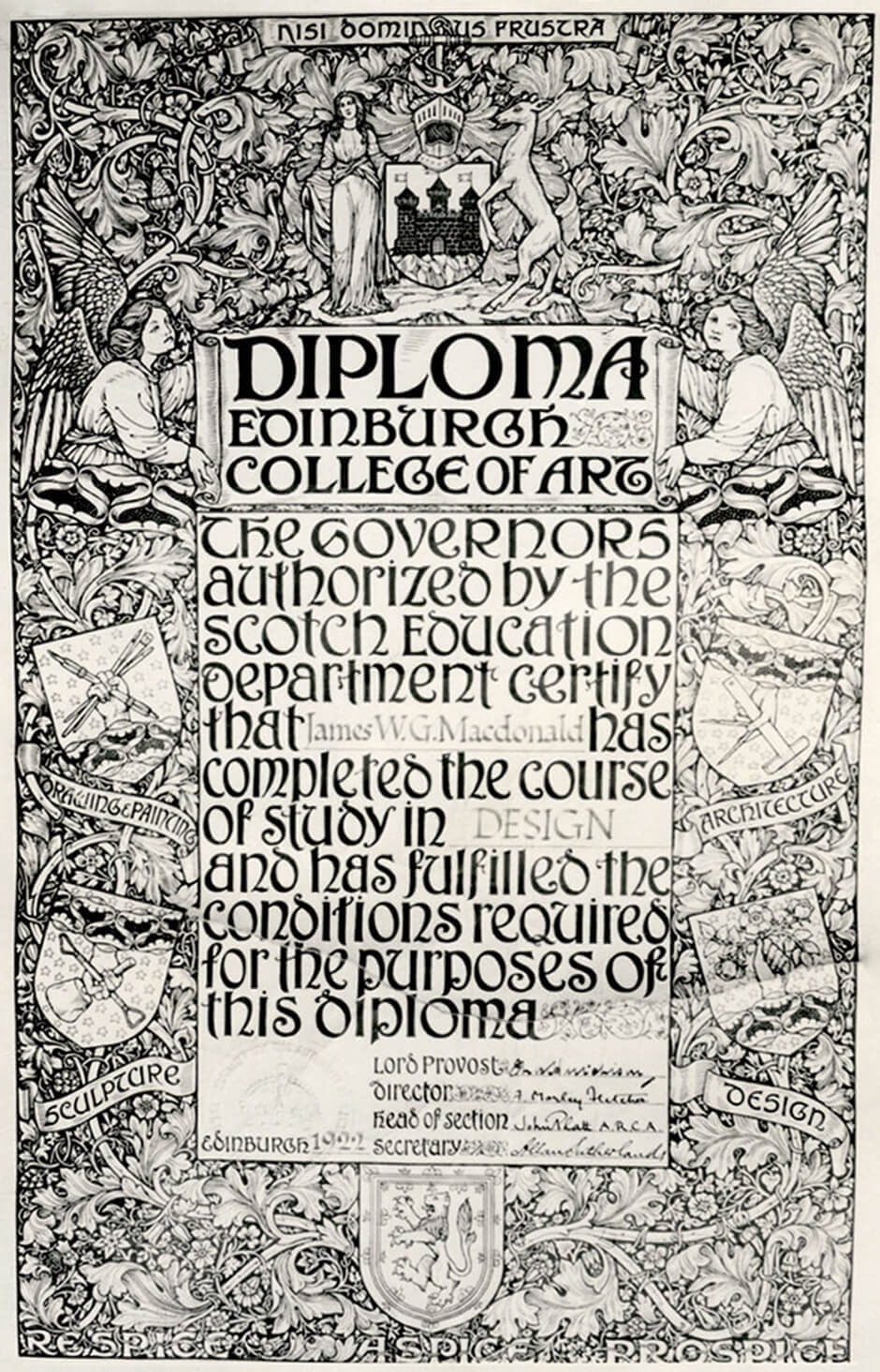

In 1919 Macdonald entered the Edinburgh College of Art and decided to major in design. There he followed the traditional art-school curriculum of drawing from plaster casts, life drawing, painting, sculpture, design, and architecture. He particularly enjoyed field trips to London, where he drew objects in the Victoria and Albert Museum with the other students and visited art galleries on his own. Macdonald also registered in the national teacher-training program. In 1922, when he graduated with a diploma in design from the Edinburgh College of Art and an art specialist’s teaching certificate from the Scottish Education Authority, he was awarded the design travelling scholarship as well as the prize in woodcarving.

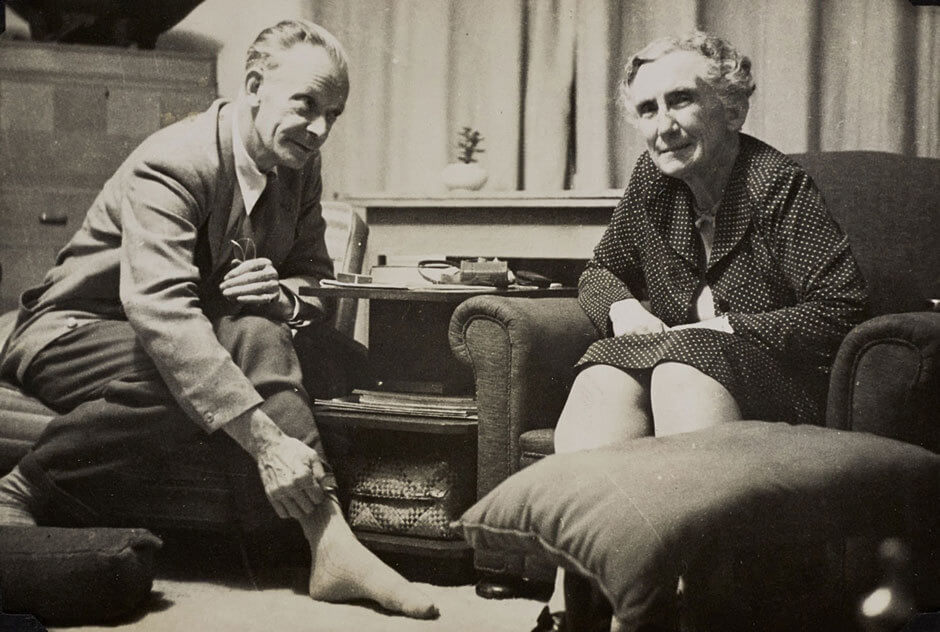

That same year, Macdonald married Barbara Niece, a fellow student who had majored in painting. Although she never pursued a professional career, she became his best critic and strongest supporter.

Design and Teaching

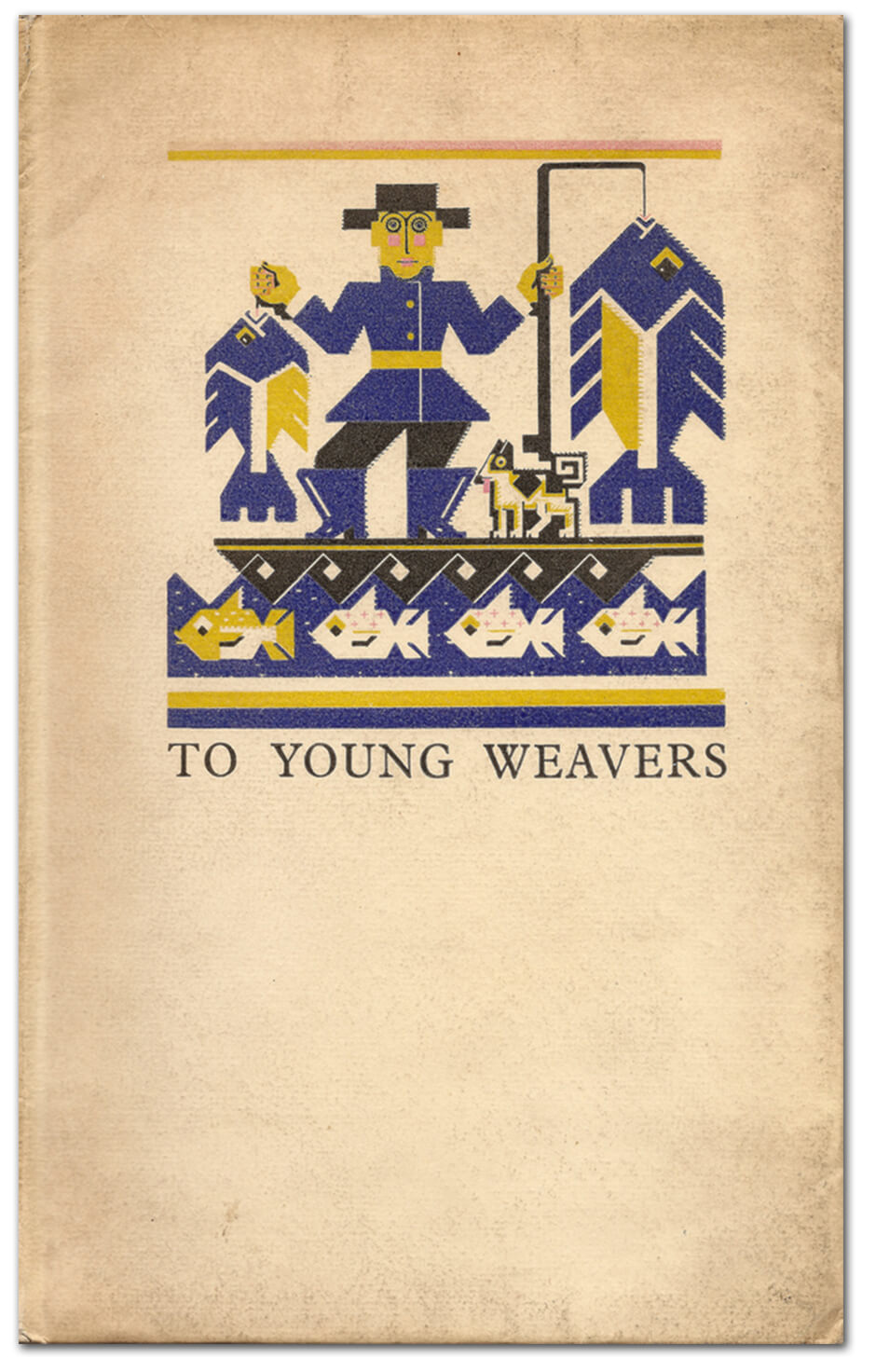

While still a student, Macdonald did freelance design work for the Edinburgh office of Morton Sundour Fabrics. The company included Liberty of London and Holyrood Palace among its clients. On graduation, Macdonald was appointed staff designer at Morton Sundour’s head office in Carlisle, England, where he created designs for every type of fabric—textiles, tapestries, and carpets. He remained at the firm for more than three years and became director of the handloom rug-weaving department. He remembered the job as incredibly demanding: “I found myself clocking in at 8 a.m. at the factory gates…. They wanted hundreds of [designs] … new, effective, full of vitality, interesting and withal simple, not forgetting the cost of production.”

In 1925 Macdonald left Morton Sundour to become head of design at the Lincoln School of Art in England. A year later, excited by the idea of new opportunities, he successfully applied for the position of head of design at the recently established Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts (now the Emily Carr University of Art + Design). He arrived in Vancouver in September 1926—and for the rest of his life he would teach as well as paint.

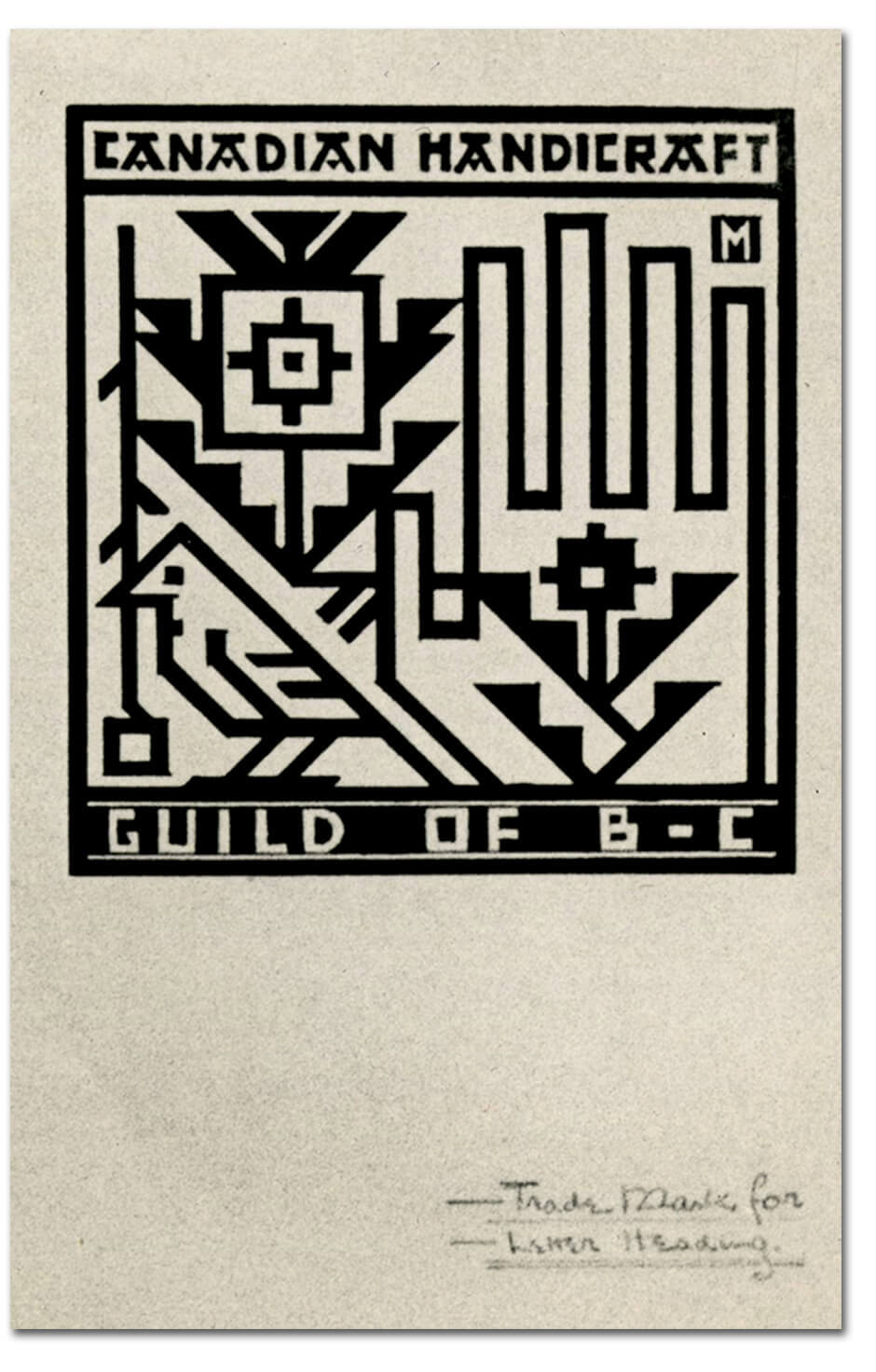

Although Macdonald was very busy with his teaching and administrative duties at the school, he also found time to do some design work. He created one of his first West Coast landscapes, the Art Deco Burnaby Lake, c. 1929, for a poster competition sponsored by the B.C. Electric Company.

New Aesthetic Expressions: Vancouver

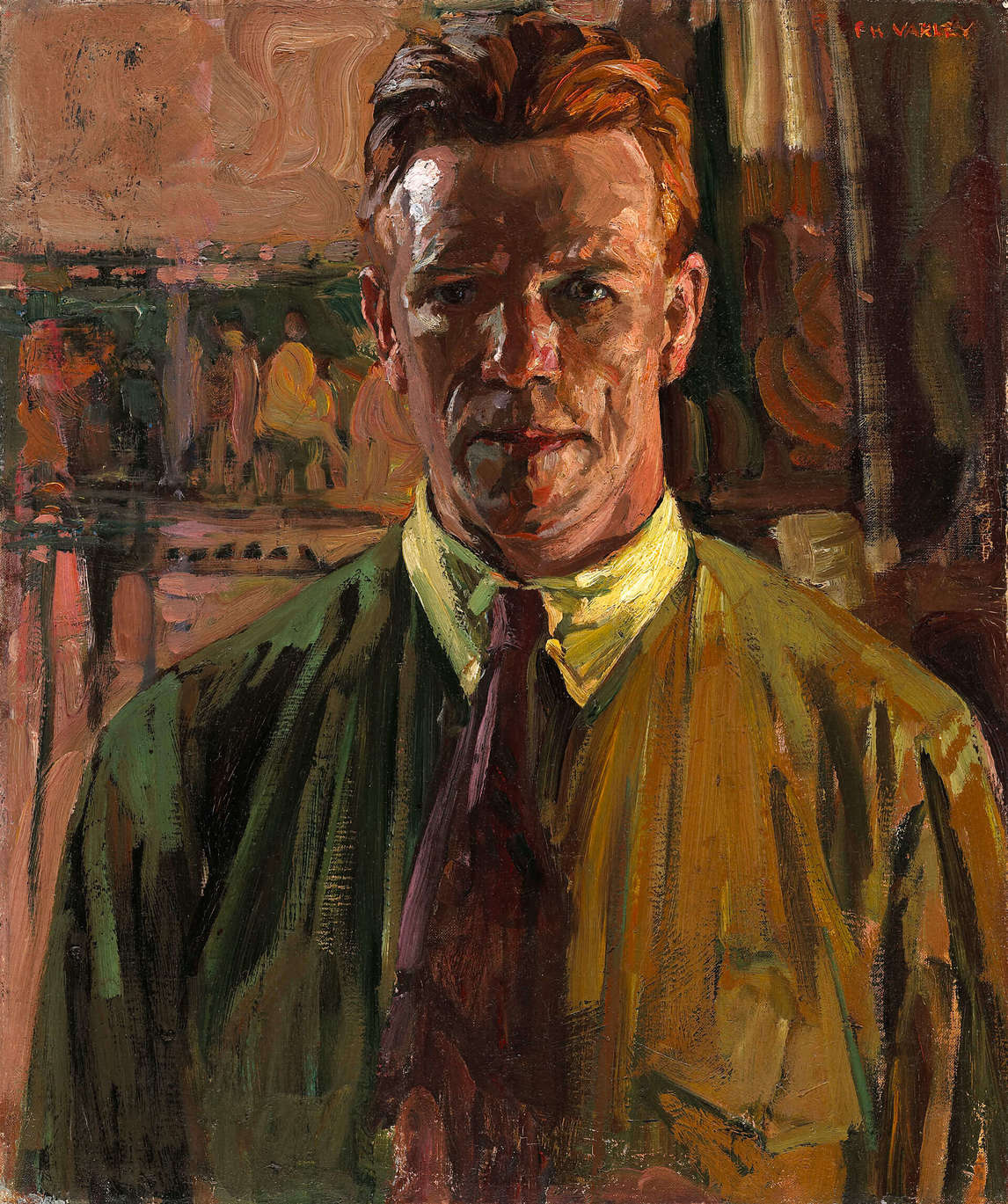

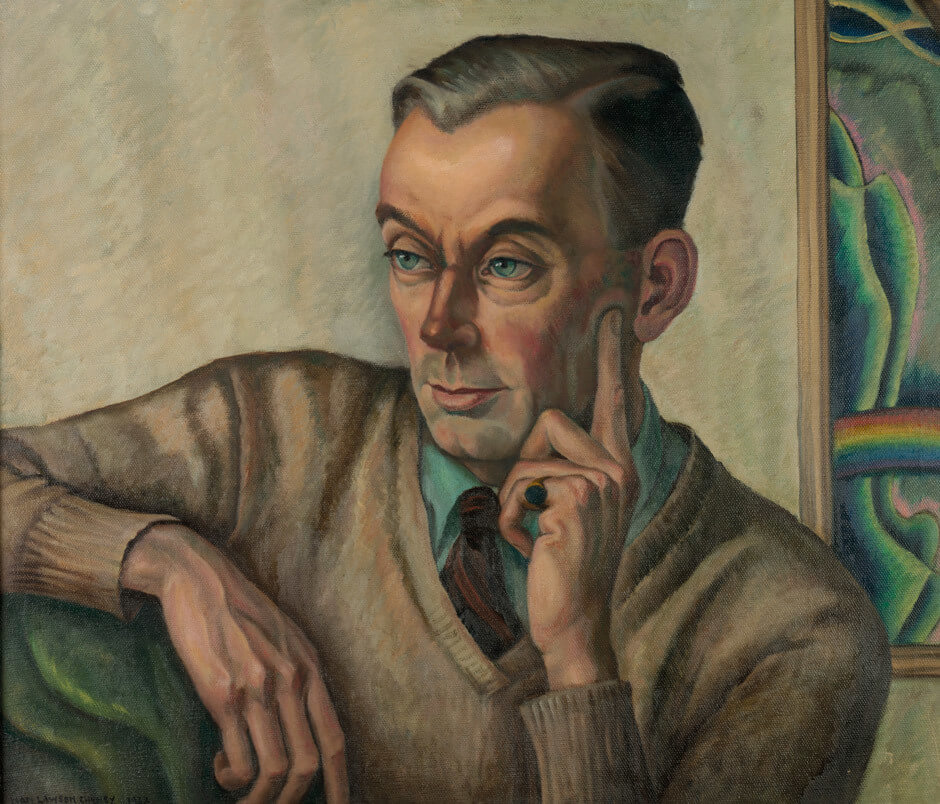

The late 1920s was an exciting time in Vancouver—a dramatic change from the staid Victorian art scene that had discouraged Emily Carr (1871–1945) in 1913 when she abandoned painting for over a decade. The creation of the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts (VSDAA) was central to the shift, as was the arrival in the city of two men: Fred Varley (1881–1969), the renowned Group of Seven landscape and portrait painter who was the first head of drawing, painting, and composition at the school; and John Vanderpant (1884–1939), an internationally recognized photographer. Both were to have a profound influence on Jock Macdonald.

Varley fell in love with the British Columbia landscape and organized sketching trips for his colleagues and students. Macdonald began to focus on painting and shared a studio with Varley, who became his mentor. Recognizing that the grandeur of the landscape required a stronger medium than the watercolour and tempera of his earlier work, Macdonald began to paint in oil (Lytton Church, B.C., 1930; The Black Tusk, Garibaldi Park, B.C., 1932; Table Mountain, Garibaldi Park, B.C., 1934). The powerful connection he made with the rugged B.C. scenery, his spiritual identification with nature, and his determination to capture the experience of the landscape in paint set him on the quest that would shape his painting for the rest of his life.

In 1926 Vanderpant and Harold Mortimer-Lamb (1872–1970) opened the Vanderpant Galleries, which exhibited contemporary art and photography and promoted B.C. artists. The gallery soon became a force for modernist art in Vancouver and, between 1928 and 1939, a gathering place for the city’s intellectual and artistic communities.

Although Vancouver remained a conservative city culturally, an increasing number of residents were attracted to new ideas, and particularly to Eastern thought and spiritual concepts. In April 1929 a crowd filled the Vancouver Theatre to capacity, and thousands more stood in line to hear the poet-philosopher Rabindranath Tagore, who “carried the audience into the realm of pure aesthetics.” For the artistic community, the Vancouver scene in the late 1920s and early 1930s might be summed up in Fred Varley’s advice to his students to “forget anything not mystical.” In 1932 Macdonald painted In the White Forest—an image that represents a distinct shift in his work and the beginning of his lifelong search for the spiritual aspect of nature in art.

These heady days were not to last. With the onslaught of the Depression, the VSDAA cut faculty salaries drastically. When Macdonald and Varley realized that the burden was not shared fairly, they were outraged and in early 1933 resigned in protest.

The British Columbia College of Arts

Almost immediately, Macdonald and Fred Varley (1881–1969) announced that they would open a new school, the British Columbia College of Arts, in September that same year. The college’s educational philosophy, steeped in contemporary European modernist art and aesthetic theory and based on the anthroposophical beliefs of the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925), was designed to bring all the arts together. Ambitious to “develop a new art movement,” its multidisciplinary curriculum drew “from the east and the west the powerful forces of the art world, welding them together on the B.C. Coast.”

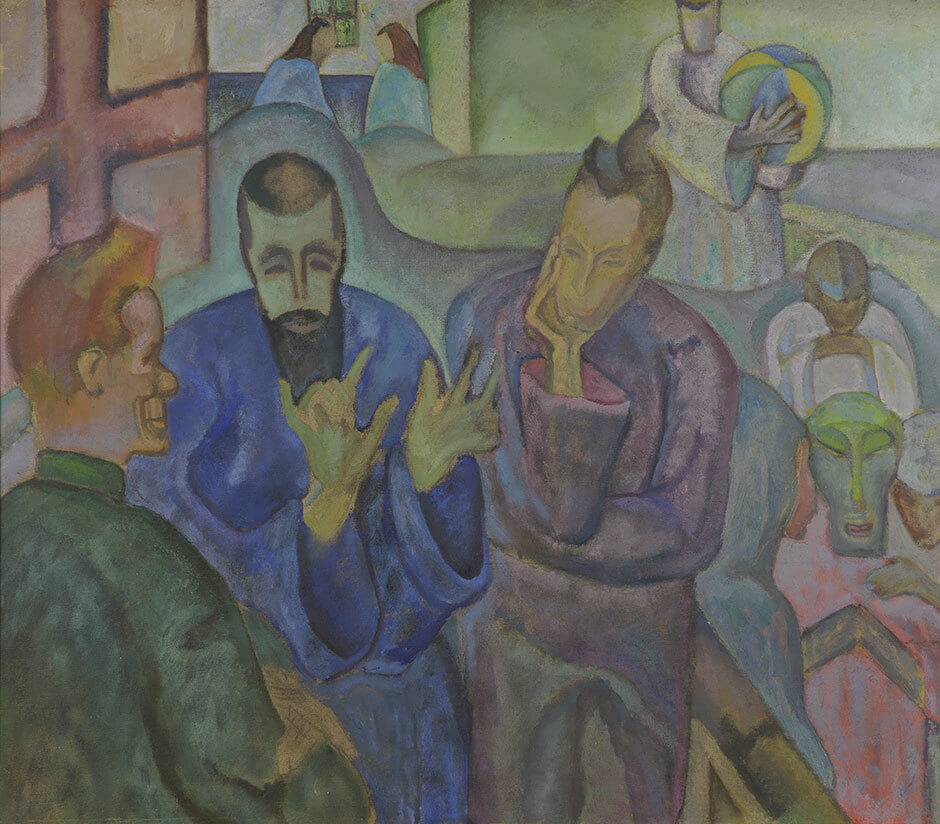

The college was housed in a former automobile showroom. Varley, the college’s president, taught drawing, painting, portraiture, mural decoration, and book illustration; Macdonald, the first vice-president, oversaw industrial design, commercial advertising, colour theory, woodcarving, and children’s art classes; and Harry Täuber, a European stage and costume designer who had recently arrived in Vancouver, was second vice-president and taught architecture, film, theatre arts, and art and metaphysics. Steeped in this experimental milieu, Macdonald painted Formative Colour Activity, 1934—his first semi-abstract painting, a visual analogue for the ideas that began to obsess him.

Though the college was a great academic success, tuition fees and limited private funding were not enough to support its operations. In 1935 the college closed, and Varley and Macdonald went their separate ways. The always-scrupulous Macdonald assumed responsibility for shutting it down in an orderly way and covering the outstanding debts from his own limited funds, so it would not leave a “bad odour.” Bitterly disappointed, and with no teaching prospects in sight, he sought a fresh start.

Nootka: The First Breakthrough

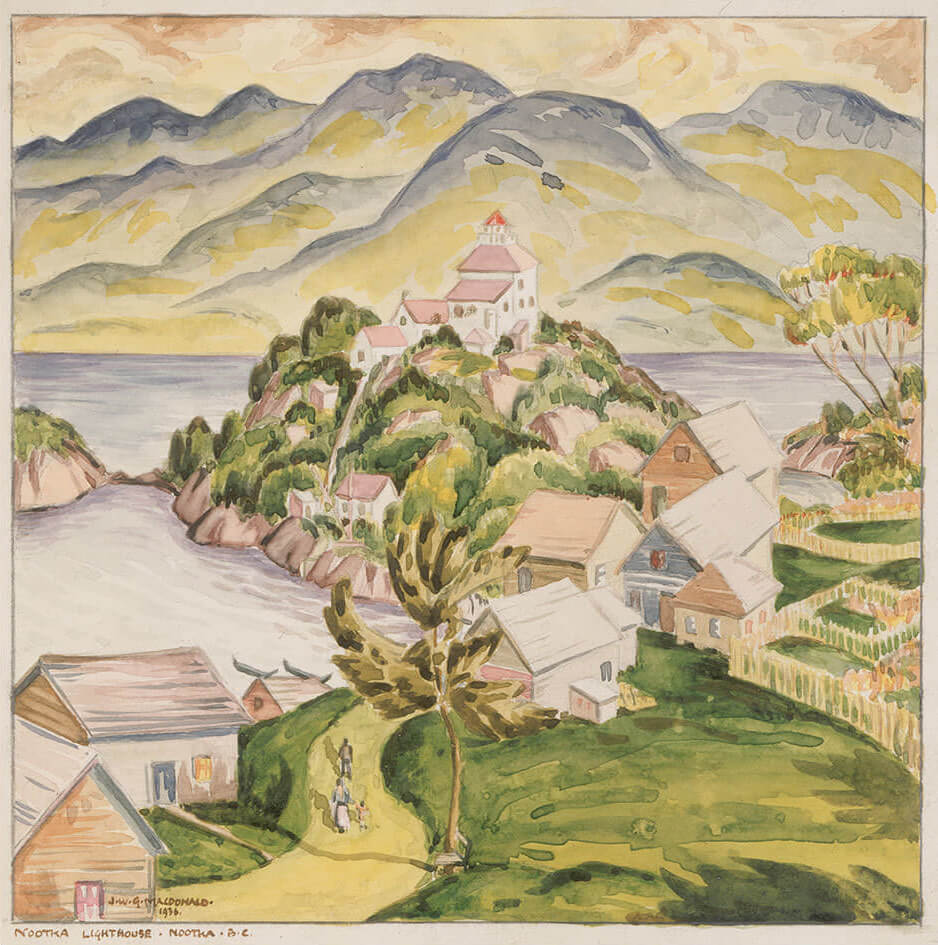

On June 19, 1935, Macdonald, his wife, Barbara, and their seven-year-old daughter, Fiona, along with Harry Täuber and his lover Leslie Planta, boarded the SS Maquinna. Their destination was Friendly Cove (Yuquot), a Nuu-chah-nulth (Mowachaht) village on Nootka Island off the west coast of Vancouver Island—the site of the first sustained contact between Europeans and the First Nations people of British Columbia.

Macdonald envisioned this sojourn as a time when he would work closely with nature in his art, in the hope of finding a “spiritual expression.” But he also had another purpose in mind—the creation of an artists’ colony. Before leaving, he had asked the land surveyor’s office which properties in the Nootka Sound area were available for purchase. The group landed with living and building materials, art supplies, and extensive reading materials.

Macdonald spent the first few months engaged in hard physical labour, chopping wood, and fishing for food. Searching for a suitable piece of land, he travelled by boat through rough seas and made his way through dense growth on shore. Evenings offered a respite—a time for reading, study, listening to music, and communal discussions. But the opportunity for camaraderie proved short-lived. Täuber preferred to read than to do practical work, and in December he and Planta left the makeshift settlement.

Unable to locate a suitable piece of land, Macdonald settled with his family in an abandoned cabin. Desperately needing money, he wrote in his diary, “I painted and sketched as much as I could during this time, in the hope that I might sell a sketch + have some funds again.” In December he sent his dealer, Harry Hood at the Vancouver Art Emporium, nine oil-on-board sketches as well as Friendly Cove, Nootka Sound, B.C., 1935, the only work on canvas he completed during his sojourn in the Yuquot area, and Formative Colour Activity, 1934, which he asked to have forwarded to the first Canadian Group of Painters exhibition in Toronto. The sale of Friendly Cove for $350 to the Clegg family solved his cash crunch over the winter, but the challenges of the harsh conditions continued.

Two paintings reflect Macdonald’s complicated relationship with the ocean, on which he and his family depended for food and transport. Graveyard of the Pacific, 1935, captures the tremendous power and “fury” of the ocean—“The sea is … 20 feet high + thundering up the beach,” he wrote. “The horizon is a mass of foam + high rolling waves.” Pacific Ocean Experience (also titled Myself in a Nine Foot Boat), c. 1935, represents a very different perspective on the ocean. Safely contained within a protective mandorla, the artist seems at one with the swelling seas as two whales cavort around him. The smallness of the figure emphasizes its isolation, but the strange vantage point emphasizes that he is protected in the womb of nature.

In March 1936 the Macdonalds were joined by artist John Varley (1912–1969), the son of their former colleague, but he stayed only seven months. During that time, Macdonald injured his back, and he despaired of staying on with only his family over another winter. “We might as well starve beside friends,” he wrote, in deciding to return to Vancouver.

The realization that they would soon be leaving seems to have stimulated Macdonald to focus on his original artistic objective for going to Nootka—the search for a new abstract artistic expression based on a spiritual relationship with nature. On October 5, 1936, he made the breakthrough that shaped his aesthetic quest over the next decade. In just three weeks he experienced a series of revelations, each of which led to a new work. He was, finally, creating something unique, “an expression all [his] own.” Many of the ideas came in the evening as he sketched, and he worked his drawings into paintings the next day. In the oil-on-board works Departing Day, 1936, and Etheric Form, 1936, he portrayed his concept of the solar system in richly vibrating imagery. Though Macdonald described this breakthrough as spontaneous, it was the result of years of reading, study, and contemplation.

On October 24 Macdonald wrote in his diary that he had received an offer of a part-time job at the Canadian Institute of Associated Arts, a private vocational school. “Here is hope at long last,” he wrote. “I feel that I have work to do in Vancouver + I intend on sailing right in.” On November 27, after nearly eighteen months, the Macdonalds left Nootka. The discoveries from this last intensive period of exploring an abstraction derived from nature—what Macdonald called his “thought forms in nature” or “modalities”—would become his major focus for the next decade.

Vancouver Again, 1936–46

The challenges of teaching in a trying environment and continuing financial pressures took their toll, and in the spring of 1937 Macdonald was confined to bed—the result, he wrote, of “undernourishment together with over-exertion … during physical duties on the West Coast.” He continued: “Things are … so difficult … it appears likely that I will leave Canada for further south—for a time.” That fall, after completing the requirements for a B.C. teaching certificate, he finally obtained a full-time teaching post with the Vancouver School Board, at Templeton Junior High. The following year he moved to the Vancouver Technical Secondary School, but he was continually exasperated by conservative school administrators and frustrated by the constraints on his teaching. He remained in this “purgatory” for seven years.

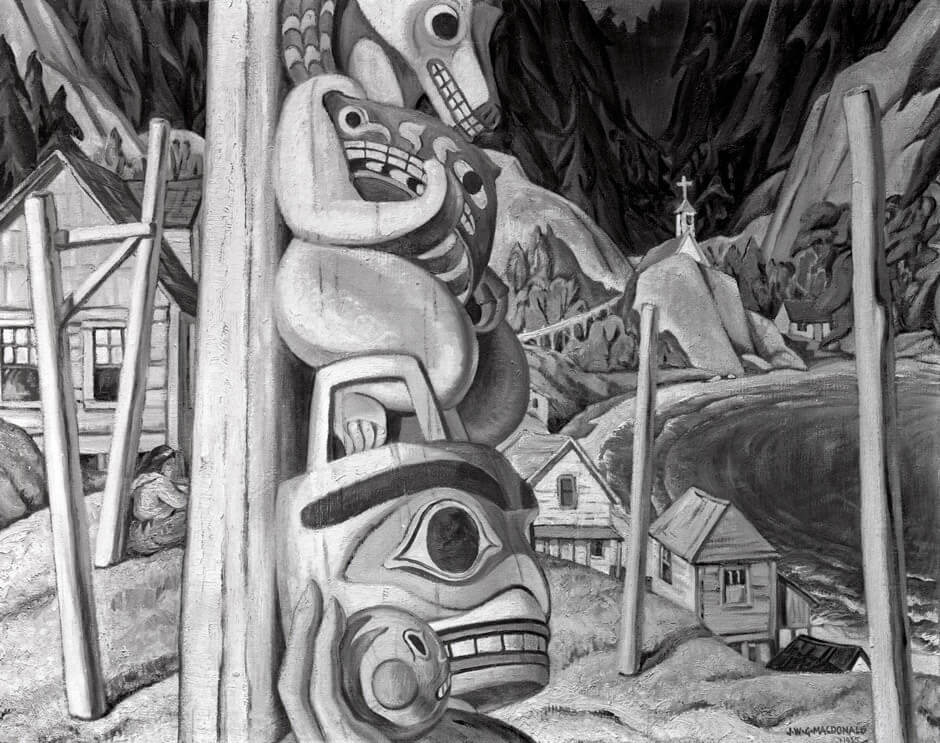

Macdonald was, however, able to find meaning in his painting, and he began working on several major canvases, derived from sketches he had made on Nootka Island, including Indian Burial, Nootka, 1937. Its purchase by the Vancouver Art Gallery provided him much-needed financial relief.

By May 1938 he had almost completed the brilliant Drying Herring Roe, 1938—a work he described as “typically West Coast … pure in colour and direct in composition.” This painting, along with the more abstract Pilgrimage, 1937, was selected by the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa for the Century of Canadian Art exhibition that the gallery was organizing for the Tate Gallery in London. In 1939 Macdonald undertook a large mural (now destroyed), also drawn from the Nootka landscape, which was commissioned for the dining room of the new Hotel Vancouver. Macdonald later wrote of this work: “I am sure [it was] one of the first semi-abstract murals done in Canada, if not the first.”

In the summer of 1939 the Macdonald family set out in a borrowed car for California. Macdonald found the art exhibition at San Francisco’s Golden Gate International Exposition “simply excellent, quite the finest collection of work I have ever seen—a fine collection of original Van Goghs, two Gauguin, several Braque (an amazing aesthetic artist—in design and colour), Matisse, Picasso, Léger, Marc, Kandinsky and every other notable.” In Los Angeles he saw Guernica, 1937, by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), where it was exhibited to raise funds for Spanish refugees. The Macdonalds arrived home at the end of August “full of cosmic vibrations.”

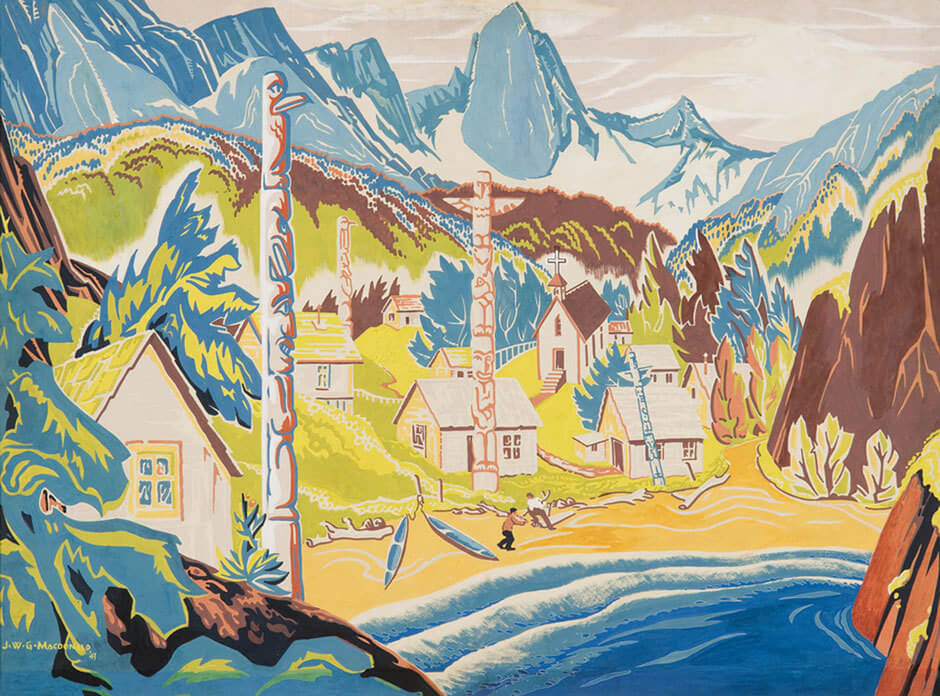

In 1943 Macdonald would return to the subject of the Nootka community and landscape once again with his composite image B.C. Indian Village, having been invited to participate in the National Gallery’s wartime silkscreen project. The gallery’s partnership with the printing and design firm Sampson-Matthews has been described as “an incalculable service to the armed service,” one that would “greatly aid in spreading an understanding and appreciation of Canadian art.” The prints were distributed to military bases across Canada and abroad, and later to schools in every province.

On his return to Vancouver in late 1936, Macdonald had continued his explorations of the semi-abstracts he had begun during his last intensive weeks on Nootka. Considering them works in progress, he initially kept them a secret from almost everyone in Vancouver except his old friend John Vanderpant (1884–1939), who had experimented with abstraction drawn from nature in his photographs and had inspired Macdonald’s own work. For Macdonald, these modalities, which were “by far the most advanced painting being produced in British Columbia” at the time, were “much more exciting than the landscapes.”

In April 1938 Macdonald exhibited four of these semi-abstract paintings, including Rain, 1938, with the British Columbia Society of Fine Arts at the Vancouver Art Gallery. He reported to H.O. McCurry, director of the National Gallery, that they “stimulated a surprising number of visitors to the studio—demanding private views and numerous requests for purchases,” and that he hoped to have a “complete one-man show in Eastern Canada or the U.S.” Describing the spiritual power of these works, he wrote: “My enthusiasm for expression in the semi-abstract—or my ‘modalities’ … lift me out of the earthliness, the material mire of our civilization.”

Macdonald also shared his experiments in abstraction with Emily Carr (1871–1945), whose work he had long admired. Describing her as “the first artist in the country and a genius without question,” he strongly urged the National Gallery to acquire her paintings. “The deep inner significance of this artist is tremendous,” he wrote. He purchased her Young Pines in Light, c. 1935, for his own collection.

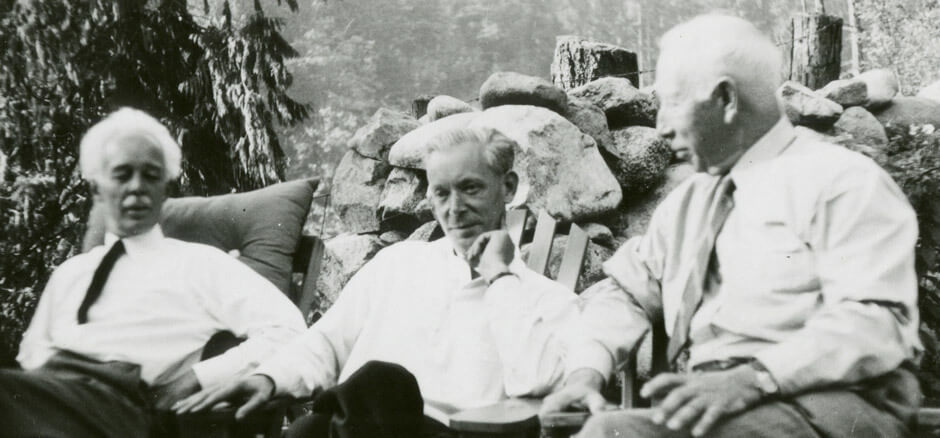

When Lawren Harris (1885–1970) moved to Vancouver in 1940, Macdonald once again had an artist-confidant with whom he could share his passion for the land and his commitment to abstraction. They enjoyed going on sketching expeditions together. Macdonald had read Harris’s writings on the spiritual in art in The Canadian Theosophist and the 1928–29 Yearbook of the Arts in Canada and shared with him the belief that nature represented a spiritual source for artists. Indeed, Macdonald had admired Harris’s work, particularly his powerful northern landscapes, since he was introduced to it in the late 1920s. In 1938 Macdonald had advised the National Gallery to include Harris’s abstractions in the exhibition it was organizing for the Tate Gallery in London: “They … hold a significant meaning in creative thought.”

In February 1940 Macdonald gave a seminal lecture at the Vancouver Art Gallery, entitled “Art in Relation to Nature,” in which he explained his artistic philosophy. Based on his knowledge of contemporary mathematical, scientific, and artistic theories, it outlined the philosophy that guided him as an artist and his commitment to making art that reflected the truth of the time in which he lived. The following year he was elected president of the British Columbia Society of Fine Arts and represented the province at the landmark Kingston Conference, the first national gathering of Canadian artists.

Renewal: The Automatics

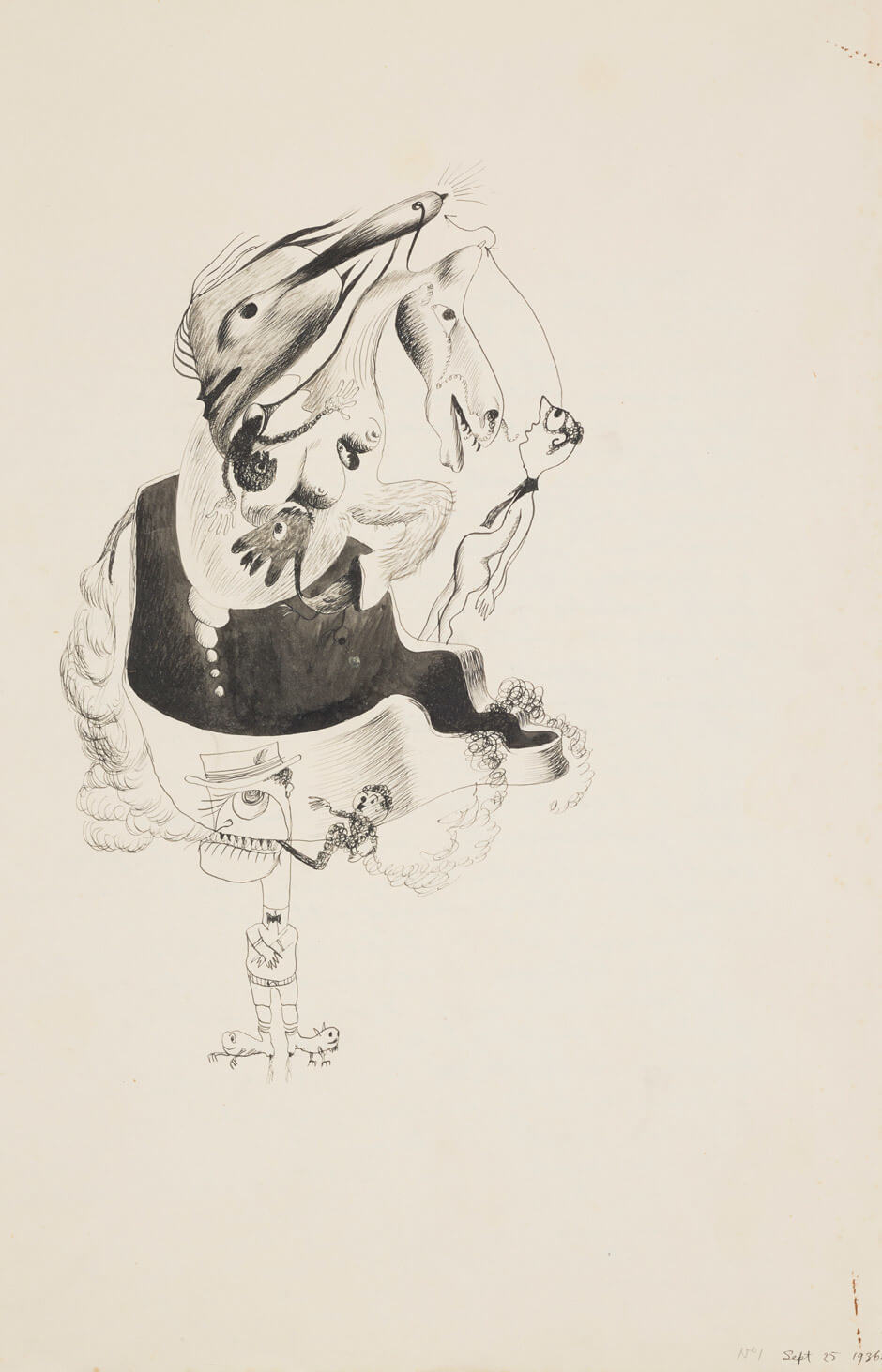

In the mid-1940s Macdonald met the British Surrealist artist and psychiatrist Dr. Grace Pailthorpe (1883–1971) and her colleague, artist-poet Reuben Mednikoff (1906–1972), who lived in Vancouver for four years while Pailthorpe was on staff at the provincial psychiatric hospital, Essondale. Their theory of automatic painting would radically change Macdonald’s approach to painting and shape his art for the rest of his life. André Breton (1896–1966), the leader of the Surrealist movement, had hailed Pailthorpe’s and Mednikoff’s work in 1936 as “the best and most truly surrealist.”

In April 1944 Pailthorpe gave a lecture on Surrealism at the Vancouver Art Gallery to an overflow audience and in June the gallery mounted a two-person exhibition of her and Mednikoff’s work. In November Macdonald participated in her lecture-demonstration on automatic art for the Vancouver chapter of the Federation of Canadian Artists. Pailthorpe asked the audience to respond “very quickly, and without hesitation” to an automatic work and to write down what the picture conveyed. She described automatic imagery as “hieroglyphic inscriptions of memories buried deep in the unconscious mind.”

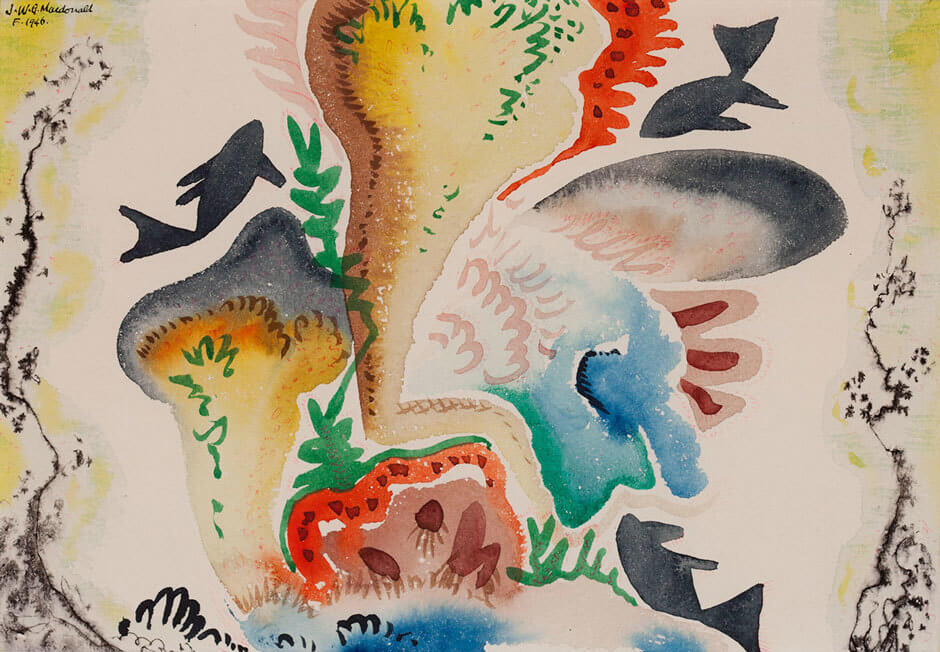

In the fall of 1945 Macdonald spent three months in intensive study of the automatic process with Pailthorpe and Mednikoff. The sessions offered the next critical stepping stone in his search for a fully realized abstract expression. Over the following seven years, in works such as Russian Fantasy, 1946, he produced a series of automatic watercolour paintings that received much praise. His art became freer and more open, and he experienced a joy he had not known before in his painting. Lawren Harris (1885–1970) considered these paintings “simply magnificent.”

In 1946 the Vancouver Art Gallery held an exhibition of Macdonald’s automatic watercolours. Grace Morley, the director of the San Francisco Museum of Art (now the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art), saw it and, declaring there was “nothing like this form of automatic statement anywhere in the world,” arranged a solo exhibition of forty-eight of these works at her gallery in 1947. She told him, “Your glorious color makes me drunk, your design work is altogether satisfying and superb.” In November the same exhibition was mounted at the Hart House Gallery at the University of Toronto.

Pailthorpe became a lifelong mentor and confidant for Macdonald, even after she returned to England in 1946. He corresponded with her and Mednikoff regularly about the progress of his work and his career, and to them he was a star student. He wrote:

I feel that I so greatly need your friendship and advice that I would undoubtedly be isolated and alone without it. Never can you know how indebted I am to both of you for the awakening and releasing of my inner consciousness. Your coming to this distant outpost has been an initiation for me, into the higher plane of creative understanding—one of the most marvelous enrichments in my life.

Despite his stimulating friendships and the fulfillment of his artwork in Vancouver, Macdonald remained frustrated and despairing about his teaching situation. In 1946 he learned of an opportunity as head of the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art in Calgary and decided to apply. When he heard he had been appointed, he exulted to Pailthorpe: “I am out of prison at last, after seven years.”

The art critic for The Vancouver Daily Province wrote that Macdonald’s departure meant “a distinct loss for the Art world of British Columbia. [His] paintings … have been much admired through Canada and overseas. [His] active co-operation with our leading Art organizations has not only furthered Art in this province, but made for his many friends who will greatly regret his absence.”

Out on a Limb in Calgary

Macdonald soon discovered that the situation in Calgary had its own challenges. “Since coming to the art department … I have been in one big fight,” he wrote. “The understanding of art + appreciation of art is dreadfully low in the city. Never have the art conscious people been even slightly introduced to 20th century expressions…. There is work for us to do here and that is quite stimulating.”

Encouraged by the response he received after a lecture he gave at the Calgary Sketch Club, Macdonald enthused, “When eventually we get [proper accommodation], we can gather in our new friends, listen to good music, and paint again.” Among these friends was the architect-artist Maxwell Bates (1906–1980), with whom he enjoyed a rich, lifelong correspondence. Invited to speak to the Alberta Society of Artists, Macdonald predicted that his talk on present-day trends in art would eat “into the old fashioned doctrines worshipped here.” After a few months, he gave up on the existing artists’ organizations and founded the progressive Calgary Group.

At the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art in Calgary, Macdonald revised the curriculum, introducing a “general course + an experimental course…. No longer were we to be an insane asylum.” The result was a significant increase in enrolments, the large majority of them veterans wanting a quick course in commercial art. At the same time, he determined, “they will get the creative + experimental work I can push into them.”

Macdonald’s first year of teaching bore immediate fruit: “Everyone admitted that [the graduating class exhibition] was the finest art school exhibition ever seen here.” To promote his students’ avant-garde work, he determined to mount the exhibition again in the fall at the Hudson’s Bay Company or Eaton’s department stores, where hundreds of people could “really see it.” The school’s retention rate, never more than 25 per cent, had climbed to 90 per cent.

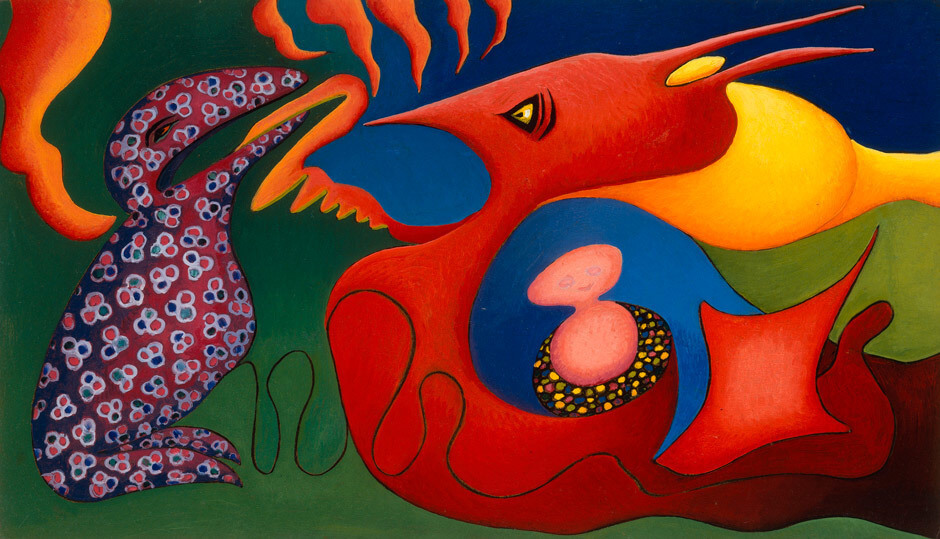

Macdonald had little time for his own painting during this busy year—and he struggled to overcome the tightness of the figurative line drawings in abstract automatics such as Orange Bird, 1946. These decorative elements, carried over from his work as a designer, contradicted the openness he sought in his painterly style.

After just one year in Calgary, Macdonald received an offer to teach at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto. He found the combination of a significant increase in salary and a more congenial cultural environment irresistible.

A New Start in Toronto

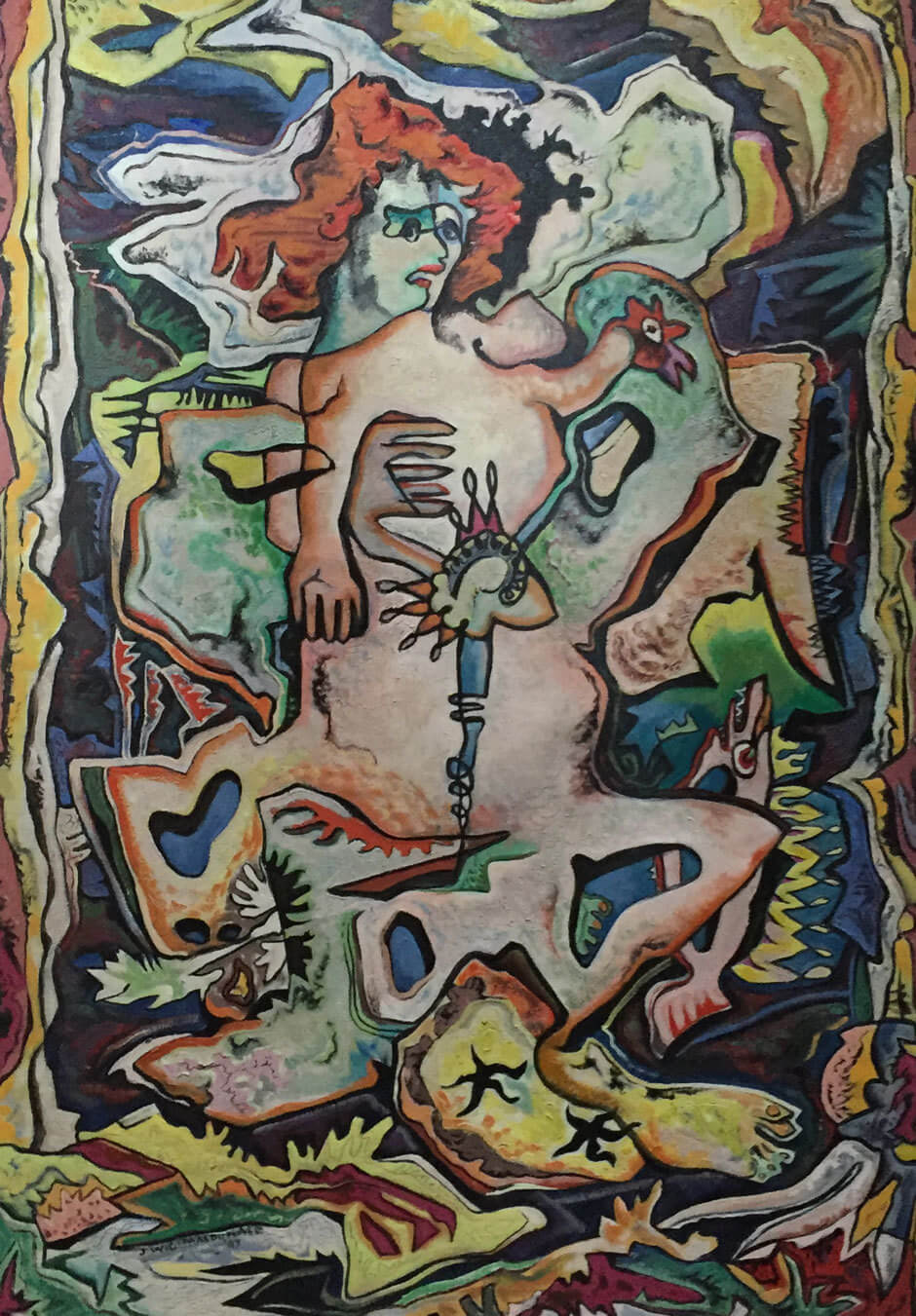

Macdonald arrived in Toronto in the fall of 1947—just as the exhibition of his automatic paintings opened at the Hart House Gallery at the University of Toronto. “It will be easier to explain my attitudes towards art in this show than for me to say it in words,” he wrote. Committed to the automatic process, Macdonald began to tackle larger and more complex works, moving from the intimacy of the earlier automatics to a more monumental scale. He was thrilled when his first automatic oil, Ocean Legend, 1947, was accepted at the annual exhibition of the Canadian Group of Painters: it was, he wrote, “entirely out of the usual line of exhibition pictures” in English Canada.

Though Macdonald quickly established himself in Toronto’s artistic forefront, he found little interest in the city in European or American modernism. The Group of Seven still dominated the art scene. It was the same at the art college, where Macdonald described the philosophy as “academic sleepwalking.” Still, he found pleasure in the opportunity to make even small inroads in the curriculum and rejoiced when his students expressed an interest in contemporary artistic expression. As in Vancouver and Calgary, he became a mentor to many of the most promising of his students: he not only introduced them to the contemporary art scene and current exhibitions but encouraged and supported them in their work.

In the summer of 1948 Macdonald joined Alexandra Luke (1901–1967) and other Canadian artists in Provincetown, Massachusetts, to work for several weeks at the studio of Hans Hofmann (1880–1966). A remarkable teacher and theorist whom Macdonald greatly admired, Hofmann immediately understood that Macdonald felt constrained by the oil medium in his automatic paintings: “All these lines that you have are crutches …,” he advised. “Colour must be the guide to composition, otherwise drawing destroys your impulse to paint.” Macdonald returned to Provincetown the following year. He wrote to Grace Pailthorpe (1883–1971) that he found Hofmann “magnificently spiritual in his personality and his attitude to art.”

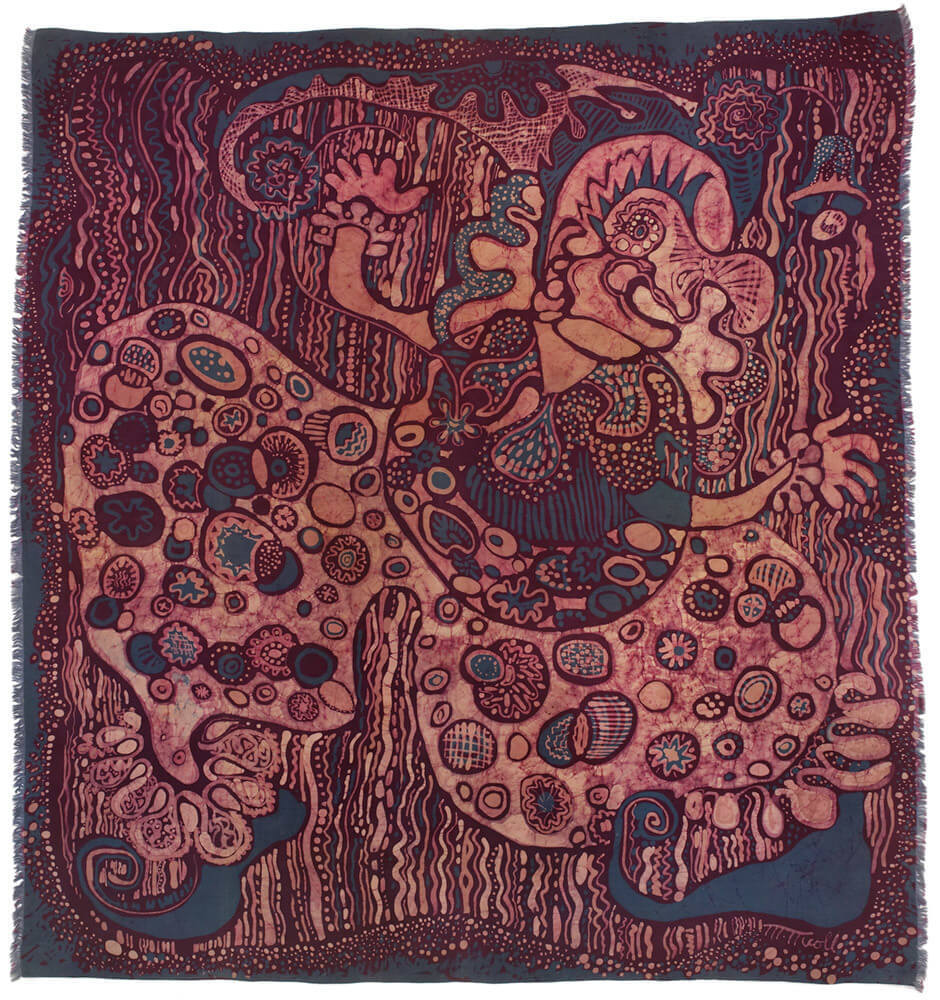

Summers offered time for additional teaching and income—particularly at the Banff School of Fine Arts (now the Banff Centre) and later at the Doon School of Fine Arts, near Kitchener, Ontario—as well as time for travel and renewal. In 1949 Macdonald was excited by an invitation to teach in Breda, the Netherlands, for UNESCO. The work he saw in the Nusantara Museum (the Indonesian ethnographic museum in Delft) inspired him to experiment with new subjects, media, and techniques. Paintings such as Eastern Pomp (Eastern Dancers), c. 1951, reflect the striking imagery and richly coloured batiks of Indonesian textiles. In the summer of 1951 at Banff he and Marion Nicoll (1909–1985) experimented by applying automatic techniques to the batik medium. Macdonald also used the wax-resist technique of batik in his paintings, and its free linear aspect and unanticipated results seemed to revitalize Macdonald’s interest in automatism.

In the summer of 1952 Macdonald was artist-in-residence at the Arts Centre of Greater Victoria (now the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria), and in August the gallery mounted a solo exhibition of his watercolours. In the explosively rich Scent of a Summer Garden, 1952, the artist abandoned all referential imagery and turned to dripping and staining colour to achieve a brilliant new sensibility. This painting, along with works such as the mystically symbolic Fabric of Dreams, 1952, earned well-deserved praise for Macdonald as the best watercolour painter in Canada.

Painters Eleven

The year 1952 saw the beginning of important changes in the Toronto art scene. In the fall, artist Alexandra Luke (1901–1967), who had studied automatic painting with Macdonald in Banff and become a close friend, organized the Canadian Abstract Exhibition at the Oshawa YWCA—and included Macdonald’s work in it. A touring exhibition, the show was mounted at Hart House in Toronto in 1953.

That same year, William Ronald (1926–1998) arranged the exhibition Abstracts at Home, which included the work of seven Toronto artists in the furniture galleries of the Simpson’s department store. Though Macdonald did not participate in the show, he joined in discussions about formally creating a group of artists dedicated to exhibiting and promoting abstract art. They called themselves Painters Eleven, and the group mounted its first exhibition at the Roberts Gallery in Toronto in February 1954. The crowds of visitors who attended the inaugural exhibition were excited by what they saw. In Macdonald’s words: “There is none so alive, creatively forceful or as talented as the members of Painters XI.”

When Macdonald was offered a Royal Society of Canada fellowship for the academic year 1954–55 to work and study in France, he jumped at the opportunity. For the first and only time in his life, he was able to travel and paint without pressure to earn a livelihood. His ultimate destination was the south of France. He found working conditions ideal in Vence—living “up against the mountains,” in the village “where Braque, Picasso & Léger spent considerable time.” The landscape paintings from this period include a number of works in which the oil paint is applied thickly with a palette knife. But it is in the watercolours, such as the exquisite From a Riviera Window, 1955, that Macdonald most successfully captures the light and sensibility of the south.

For Macdonald, one of the most important aspects of his sojourn there was his meeting with Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985), whose work he greatly admired. As he reported to a friend, Dubuffet told him, “You have not so far been able to express yourself as freely in oils as in watercolour. If only you could speak in oil as you do in watercolour … you would have a profound contribution and a personal one … you paint with too solid a medium.” Macdonald determined to try: “My aim is to find this technique and I will,” he wrote.

“Hitting Absolute Tops”

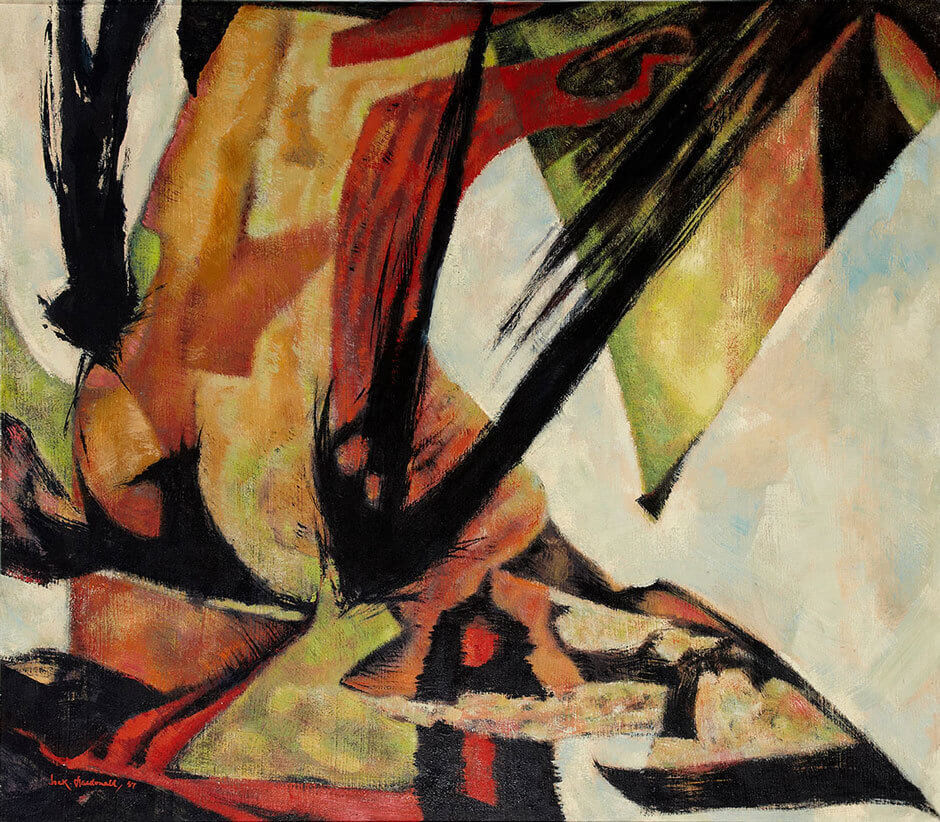

When Macdonald returned to Toronto in 1955, he found that many artists were using commercial enamel paints that were cheaper, dried more quickly than oils, and were easier to work with for painters seeking fluidity in their work. In the spring of 1956, he began to experiment with Duco and, later, with Lucite 44. “After a session of trial and error I began to get control and more feeling for painterly qualities,” he wrote. “I find my work far freer—much less tight, more painterly and frankly, I think more advanced.” Finally he had the tools required to achieve his objectives. For the rest of his life, Macdonald would go from strength to strength in his paintings.

In 1957 Macdonald, on behalf of most members of Painters Eleven, asked Clement Greenberg (1909–1994), champion of the American Abstract Expressionists, to Toronto to critique their work. Greenberg spent an afternoon in Macdonald’s studio and his comments provided a great boost to the painter’s confidence. Macdonald reported that Greenberg thought his “new work was a tremendous step forward in the right direction, completely my own and could stand up to anything in New York.” He said Macdonald was ready to free himself from the limitations imposed by the canvas—what he called “the box.” A year later Greenberg visited Toronto again and, in Macdonald’s words, “he liked nearly all my things and found my very latest ‘hitting absolute tops.’”

In 1957 Canadian Art published an article on Macdonald by Maxwell Bates (1906–1980), the first in-depth article written about his work. In November that same year, Hart House Gallery at the University of Toronto again mounted a solo exhibition of his paintings. It featured twenty-nine brilliant new works, including Airy Journey, 1957, and Iridescent Monarch, 1957, most of them in oil and Lucite 44. They are among the most satisfying and powerful abstract paintings ever created in Canada. Journalist and art critic Robert Fulford called Macdonald “without question the best young artist in Canada, even though he was born in 1897.”

Macdonald was heartened when he was invited to join the Park Gallery in Toronto. It offered him the promise of a New York show, international promotion of his work, and “a wider horizon for exhibitions.” His first solo show there in April 1958 contained an amazing sixteen new paintings, including Rust of Antiquity, 1958, which he had created since the Hart House exhibition five months before. He wrote that he had completed almost one painting a week for the previous year. In 1959 he left the gallery for Toronto’s new Here and Now Gallery when it offered him a solo show for January 1960 and better representation nationally and internationally.

Driven by the need to devote more time to his painting, Macdonald reduced his teaching load at the Ontario College of Art to four days a week. He also committed to fewer private evening and weekend classes, though he continued to teach during the summer. He was anxious, however, about the future on the meagre pension he would receive after mandatory retirement at sixty-five: “All I will get to live on after 36 years of striving to develop the art culture in Canada will be $50 a month,” he wrote. “One would think that something could have been done to give me enough to exist on and give me the chance to paint steadily until death.”

In the spring of 1960 the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario) mounted a retrospective exhibition of Macdonald’s work. He was thrilled to accept “this very unique honor”—the first such show given to any living artist who was not a member of the Group of Seven since his arrival in Toronto thirteen years earlier. In assembling work for the exhibition, Macdonald took pains to make sure that the evolution of his work was evident and that the modalities were prominently featured. Although most of the reviews were positive, Macdonald was upset by the lack of understanding by some critics of the early work, “the difficulty of the artist’s search [and] the significance of the stepping stones when they appeared.”

In November 1960 Macdonald suffered a heart attack. He wrote to his former student Thelma Van Alstyne (1913–2008) from his hospital bed: “A beautiful morning of life giving Sunshine…. The happiness, the only happiness there is, is in the constant seeking for understanding of spiritual consciousness.” It is that understanding and oneness with nature and the natural universe, as in Far Off Drums, 1960, that informed Macdonald’s search. He resumed teaching but died from a second heart attack on December 3.

Macdonald taught that “non-objective masterpieces are created intuitively—are alive with spiritual rhythm and organic with the cosmic order which rules the universe.” In his final works he achieved what he had set out to do in his modalities a quarter of a century before—to transcend the material world and find an expression of the spiritual beyond.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements