Norval Morrisseau (1931–2007) is considered by many to be the Mishomis, or grandfather, of contemporary Indigenous art in Canada. His life has been sensationalized in newspapers and documentaries while his unique artistic style has pushed the boundaries of visual storytelling. The creator of the Woodland School of art and a prominent member of the Indian Group of Seven, Morrisseau is best known for using bright colours and portraying traditional stories, spiritual themes, and political messages in his work.

Early Years

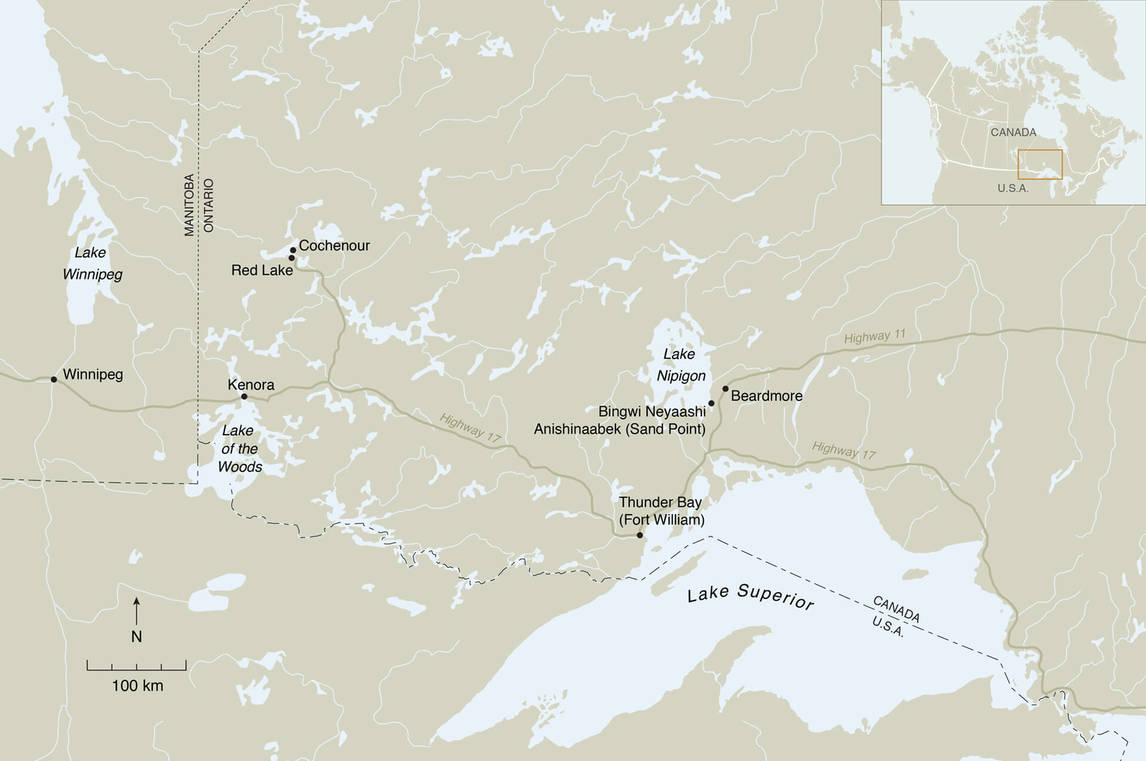

Anishinaabe artist Norval Morrisseau was born in 1931 at a time when Indigenous peoples in Canada were confined to reserves, forced to attend residential schools, and banned from practising traditional ceremonial activities. He was the oldest of five children born to Grace Theresa Nanakonagos and Abel Morrisseau, and, in keeping with Anishinaabe tradition, he was sent to live with his maternal grandparents at Sand Point reserve on the shores of Lake Nipigon, Ontario. There, Morrisseau learned the stories and cultural traditions of his peoples from his grandfather Moses Potan Nanakonagos, a shaman trained within the Midewiwin spiritual tradition. From his grandmother Veronique Nanakonagos, he learned about Catholicism.

At age six, Morrisseau was sent to a residential school, part of an education system set up by the Canadian government in the 1880s. Residential schools, which operated until the last decades of the twentieth century, forcibly separated Indigenous children from their families and forbade them from acknowledging their cultures or speaking their traditional languages. At St. Joseph’s Indian Residential School in Fort William, Ontario, Morrisseau faced sexual and psychological abuse that left him with deep emotional scars. After two years at St. Joseph’s, and two more at another nearby school, he returned to Sand Point to attend a public school in nearby Beardmore.

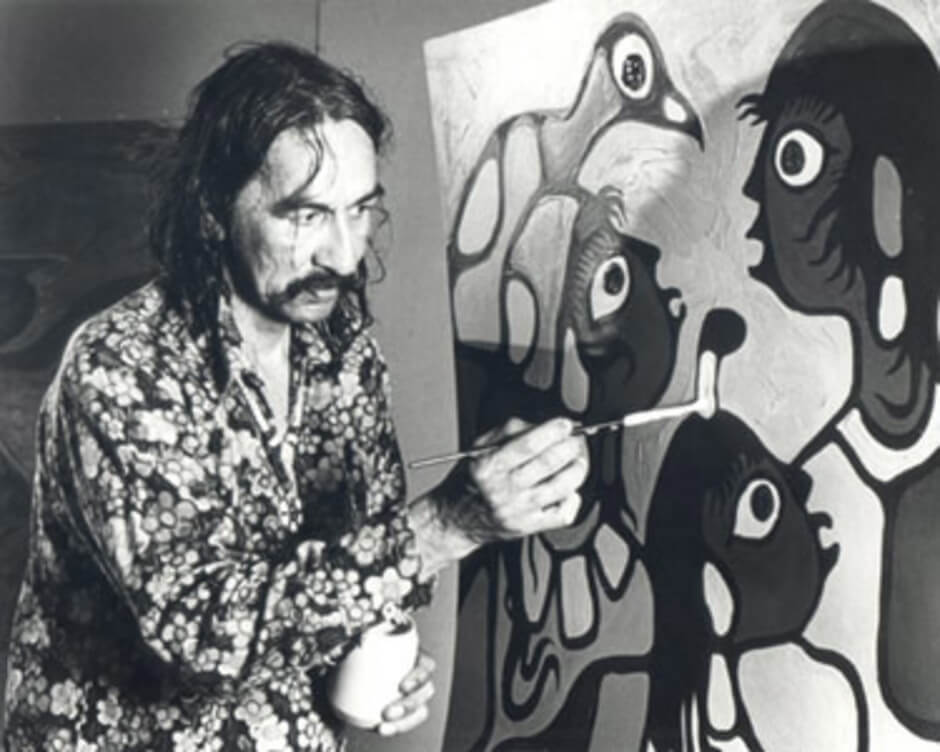

Morrisseau left school at age ten because, according to curator Greg Hill, “Morrisseau was not like other children in his community. The young artist preferred to spend his time in the company of elders listening and learning, or completely alone, drawing.” Morrisseau was interested in local petroglyphs and birchbark scroll images, but never received any formal art training. He wanted to draw things he had heard about or seen—like the sacred bear that had come to him in a vision quest, or spirit-beings such as Micipijiu or Thunderbird that were drawn on cliffs—but community members and relatives discouraged him, as Anishinaabe cultural protocols forbid the sharing of this ceremonial knowledge. When he was not drawing, Morrisseau spent time fishing, hunting, trapping, picking berries, and holding pulpwood-cutting and highway-construction jobs. In his early teens, he also began drinking alcohol.

When he was nineteen, Morrisseau became critically ill. His family arranged a healing ceremony, during which he received the name “Miskwaabik Animiiki” (Copper Thunderbird). Morrisseau explained, “That was a very, very powerful new name; and it cured me.” When he was about twenty-three, however, Morrisseau became sick with tuberculosis and was sent to a sanatorium in Fort William. There he met Harriet Kakegamic, a fellow patient from the remote northern Cree community of Sandy Lake reserve. They married in the late 1950s and lived in Beardmore, where Morrisseau began to devote more time to his art. He painted on birchbark baskets made by his mother-in-law, Patricia Kakegamic, and on other objects.

An Emerging Artist

Like many young artists, Norval Morrisseau did not earn enough on which to live. Around 1958, he found a job at a gold mine and moved with Harriet to Cochenour, near Red Lake, Ontario. There he met Dr. Joseph Weinstein, a doctor who had trained as an artist in Paris, where he had developed ties to the European modern art scene. Joseph’s wife, fellow artist Esther Weinstein, recalled a visit to McDougal’s, the local general store, where “to my surprise, I saw those two very unusual paintings [including Untitled (Thunderbird Transformation), c. 1958–60] standing on the floor.” Esther Weinstein asked the store proprietor, Fergus McDougal, to invite the artist to visit their home. Untitled, c. 1958, from that same period, may be the second painting to which she was alluding.

When Morrisseau knocked on the Weinsteins’ door a few days later with paintings to sell, the couple quickly welcomed him, and he spent many hours reading their art books and discussing art with them. Art historian Ruth B. Phillips notes that Dr. Weinstein supplied Morrisseau with high-quality art supplies, such as paper and gouache paints, and encouraged him to consider himself a professional artist “in the Western sense, rather than as a producer of tourist souvenirs.” This chance alliance between an Indigenous man and a cosmopolitan couple clearly introduced Morrisseau to a wider understanding of art, which inspired him.

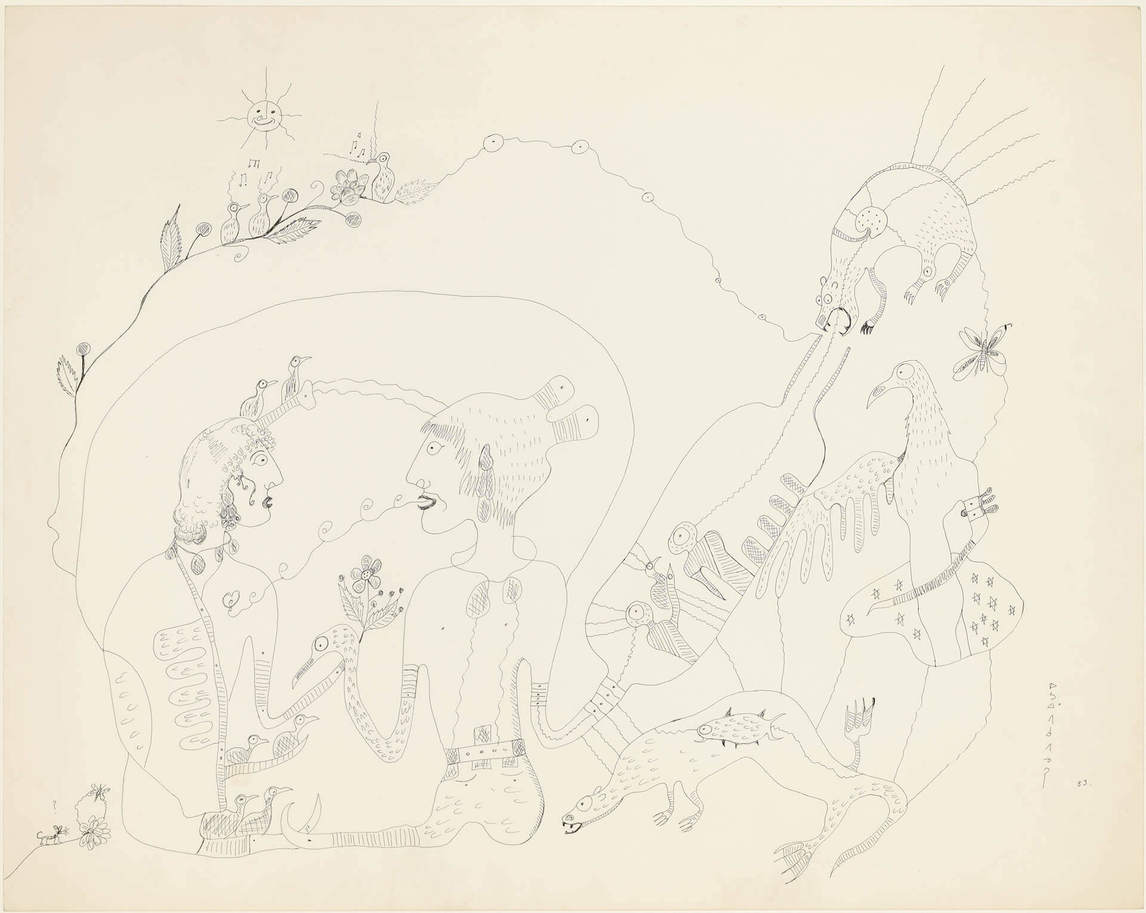

Morrisseau’s early work was also championed by Selwyn Dewdney, an anthropologist and artist who was recording pictograph sites in the area. In 1960, local police constable Bob Sheppard, who was stationed on McKenzie Island, near Cochenour, wrote to his friend Dewdney and suggested that he meet Morrisseau. The two were introduced in 1960, and, like the Weinsteins, Dewdney shared with Morrisseau his interest in modern art, including Mexican mural painting by Diego Rivera (1886–1957), Surrealist art by Salvador Dalí (1904–1989), and works by such artists as Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Henri Matisse (1869–1954). Unlike the Weinsteins, however, Dewdney initially encouraged Morrisseau to work in traditional media like birchbark and leather, though he also supported the artist’s early experimentation in oils. He also likely pushed Morrisseau to sign his work in Cree syllabics, an alphabet Morrisseau had learned from his wife. Morrisseau in turn shared his cultural knowledge of rock art with Dewdney, who studied and wrote on the subject. Their correspondence offers insight into Morrisseau’s aim to educate Canadians about Indigenous art and culture. Later, Dewdney urged Morrisseau to record a series of stories explaining the images in his art, which resulted in a book edited by Dewdney entitled Legends of My People: The Great Ojibway.

Around 1958, Morrisseau was also introduced to Susan Ross (1915–2006), a printmaker and painter from Thunder Bay who was sketching in the Cochenour area and specialized in painting portraits of local Indigenous people in a Post-Impressionist style. They became friends and Morrisseau came to depend on Ross for art supplies and answers to his questions about art. Morrisseau would send his paintings to Ross on the train from Red Lake to Thunder Bay, and he relied on her to sell them. With the proceeds from those sales, Ross bought Morrisseau art supplies and also a tape recorder so that he could better record the Anishinaabe stories told by his Elders. Their correspondence reveals Morrisseau’s growing confidence in his role as an artist and his increasing awareness of European concepts of art.

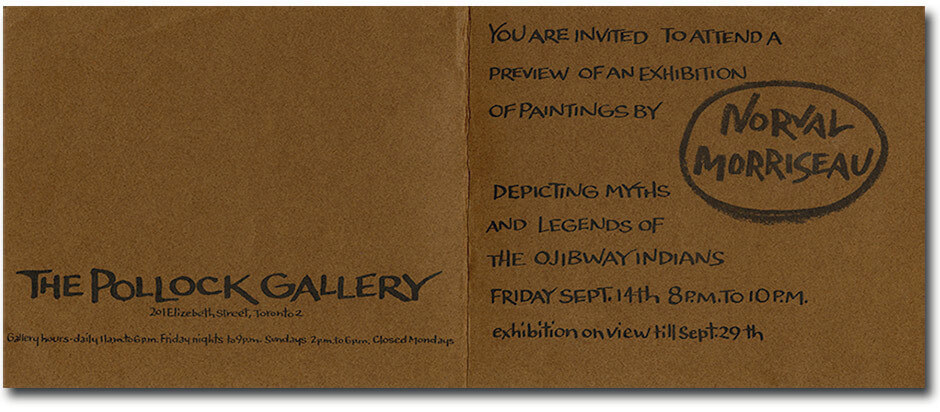

Word of Morrisseau’s art spread. Ross discussed it with Toronto gallery owner Jack Pollock, who then planned to seek Morrisseau out while on a trip to Beardmore in 1962 to teach a painting workshop sponsored by the Ontario government. Pollock later explained that it was Morrisseau who approached him. Describing Morrisseau as an odd artist with no artistic ties and living an isolated existence, Pollock noted that he was intrigued by the paintings and drawings he saw because of their “unique sense of space” and “effortless and flowing” composition. “I knew that Morrisseau was an artist with vision,” he wrote later, “and I decided then and there that I would show them [the paintings] in Toronto.”

Commercial Success

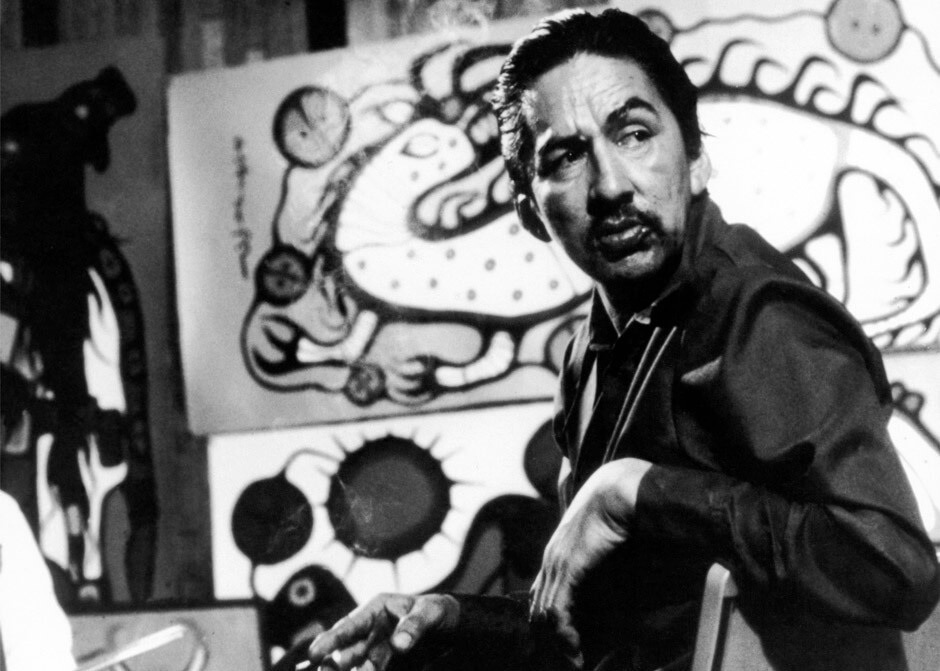

The 1962 exhibition of Norval Morrisseau’s work at the Pollock Gallery in Toronto marked the first time an Indigenous artist had shown work in a contemporary art gallery in Canada, and the media hailed the debut as a new development in Canadian art. All the paintings sold on the first day and the exhibition instantly made Morrisseau a celebrity artist and a public figure.

Yet success was a mixed blessing: both Morrisseau’s work and his private life were subjected to scrutiny. His art received mixed reviews, judged by critics as either modern or primitive or a combination of the two, and Morrisseau himself was framed as a painter of legends, in keeping with the images of the “Imaginary Indian,” the “Noble Savage,” and the “Hollywood Indian” peddled by popular culture. This stereotypical attitude was moulded by deeply entrenched colonial views and had little to do with Morrisseau as an individual or an artist. Astutely, Morrisseau defied these conceptions: he attempted to take charge of his life story by challenging interviewers and critics. For example, in the Toronto Star in 1975, he responded to art critic Gary Michael Dault’s query about the media’s scrutiny of his private life:

I am tired of hearing about Norval the drunkard, Norval with the hangover,

Norval in jail, Norval torn apart by his allegiance both to Christianity and to the old Indian ways.… They speak about this tortured man, Norval Morrisseau—I’m not tortured. I’ve had a marvelous time. When I was drinking. Now that I’m not drinking. I’ve had a marvelous time in my life.

This effort had mixed results, as press reports typically characterized his challenges as rants.

Still, Morrisseau’s paintings began to command attention in art circles, and his success generated interest in the work of other Indigenous artists across Canada. Collectors started to take contemporary Indigenous arts more seriously, and although Morrisseau was still living in Beardmore with Harriet and their growing family, he began to travel to Toronto to sell his works to dealers and to negotiate new commissions. He often relied on art dealers, politicians, and government employees to aid him in his efforts to promote his work. In 1965, the Glenbow Foundation in Calgary purchased eleven Morrisseau works, including Jo-Go Way Moose Dream, c. 1964, shown here. This significant sale led to more exhibitions, including one at the Musée du Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec) in Quebec City the following year, that signalled a growing national interest in the artist’s work.

Shortly after his exhibition at the Musée du Québec, Morrisseau was one of nine Indigenous artists commissioned to create work for the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal. His large-scale exterior mural showed bear cubs being nursed by Mother Earth, and when organizers raised concerns about this unorthodox image, Morrisseau decided to leave the project rather than censor his drawing. The mural was changed and completed by his friend and fellow artist Carl Ray (1943–1978). Through that commission, however, Morrisseau had met Herbert T. Schwarz, a consultant on the Expo pavilion, an antique dealer, and the owner of Galerie Cartier in Montreal. Schwarz encouraged Morrisseau to illustrate eight traditional Anishinaabe legends, which he published as Windigo and Other Tales of the Ojibways (1968).

Schwarz also organized Morrisseau’s first international exhibition. Based on a solo show held at Galerie Cartier in 1967, a selection of works travelled to the Art Gallery of Newport, in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1968 and then on to Saint Paul Galerie in Saint-Paul-de-Vence in the south of France in 1969. Held in an area populated by European modern artists such as Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Marc Chagall (1887–1985), this show added to Morrisseau’s credibility as an artist and established his international reputation. It is also when he became widely known as “Picasso of the North,” which is how Schwarz marketed Morrisseau in the posters advertising the French exhibition.

Morrisseau’s Decade

The 1960s established Norval Morrisseau as a noteworthy contemporary Indigenous artist in Canada, and he soon became an advocate for emerging artists. In 1971, artist Daphne Odjig (b. 1919), who owned Odjig Indian Prints of Canada Ltd., opened a small store of the same name on Donald Street in Winnipeg, which became a gathering place for artists working in the Indigenous art scene. Odjig then founded the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. (PNIAI), which came to be known as the Indian Group of Seven, to promote and support Indigenous artists throughout Canada and to change the public’s perceptions about them. In 1974, Odjig expanded her shop and established the New Warehouse Gallery, where the PNIAI’s inaugural exhibition featured more than two hundred works. At the time, work by Indigenous artists was shown in museums of anthropology or mythologized as “souvenir” art rather than being exhibited in mainstream art galleries. The PNIAI, of which Morrisseau was a key member, was featured in exhibitions in Winnipeg, Montreal, and London, England.

Morrisseau, along with his brother-in-law Joshim Kakegamic (1952–1993) and fellow PNIAI member Carl Ray (1943–1978), worked to further awareness of Indigenous art by taking part in a series of educational workshops organized by the Ontario Department of Education at local schools and community clubs in northwestern Ontario. In these workshops, Morrisseau and his artist colleagues introduced budding Indigenous artists to their approaches to painting and drawing while demonstrating a form of visual storytelling.

Around the same time, three of Morrisseau’s brothers-in-law, Henry, Joshim, and Goyce Kakegamic, formed the Triple K Cooperative in Red Lake, Ontario. It was a silkscreen company designed to give Indigenous artists control over the art they produced and access to new Indigenous and mainstream audiences. Morrisseau also began to produce graphic art, disseminating prints much more widely than his paintings and thereby strengthening an art movement built around his artistic vocabulary.

Morrisseau’s position as a contemporary artist continued to confound the museum establishment in Canada, however. In 1972, when the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto purchased eleven paintings by Morrisseau, its curator of ethnology, Dr. Edward Rogers, acknowledged it was the first time the museum had acquired contemporary paintings. The Glenbow Museum in Calgary and the Museum of Civilization (now the Museum of History) in Gatineau also purchased Morrisseau’s works, yet, like the ROM, did not know quite where to place them. Morrisseau had drawn attention to just how difficult it was for contemporary Indigenous artists to have their work taken seriously in the Canadian art scene.

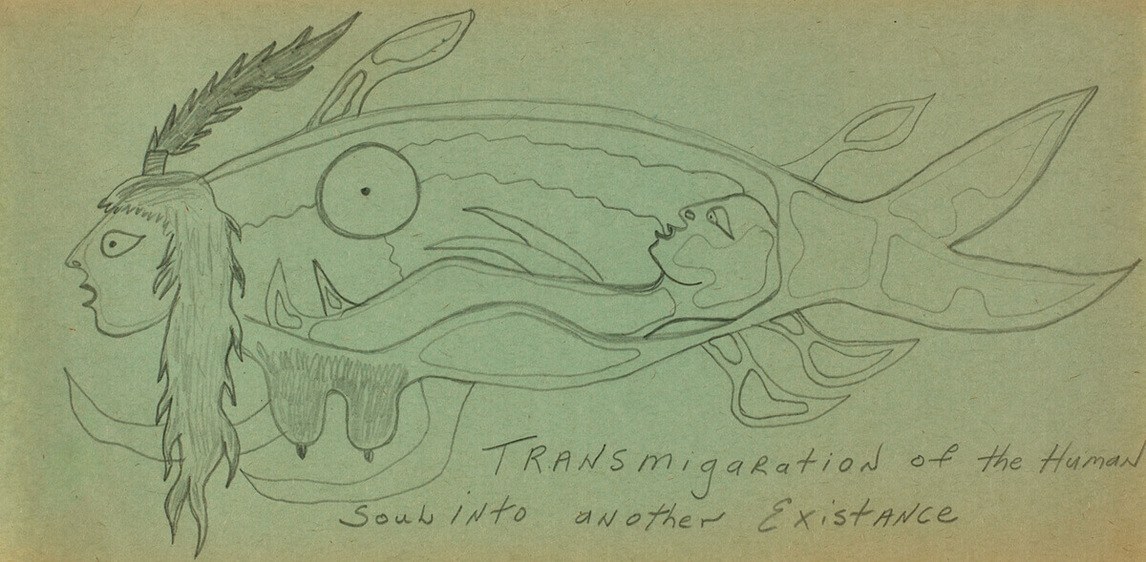

Although this period was one of immense artistic productivity, Morrisseau continued to struggle with alcoholism, which had plagued him since his youth. In 1973 he was arrested for public drunkenness and incarcerated for six months in Kenora, Ontario. Ironically, it was a highly industrious time for the artist, as he was provided with an additional cell to use as an art studio and given a lot of time to paint. While in prison, Morrisseau created a series of sketches on paper towel, including Transmigration of the Human Soul into Another Existence, 1972–73, and such noteworthy paintings as Indian Jesus Christ, 1974. Upon his release, Morrisseau became the subject of two National Film Board of Canada documentary films, The Colours of Pride (1973) and The Paradox of Norval Morrisseau (1974). While the films reflect the assimilationist movement of the time, which aimed to extinguish Indigenous cultural distinctiveness, they also raised Morrisseau’s profile in Canada and set the stage for significant public acceptance.

Eckankar: A New Spirituality

From the beginning of his career, Norval Morrisseau had featured strong Anishinaabe and Christian themes in his art; in the mid-1970s, however, he began to display a more personal hybrid spirituality. During this period, Morrisseau continued to work with art dealer Jack Pollock, whose assistant, Eva Quan, introduced him to the spiritual movement Eckankar. This doctrine combines Eastern spiritual traditions from India and China, and Morrisseau was primarily interested in two specific aspects: astral travel and spiritual light. “Through Eckankar, Morrisseau develops a vocabulary for his shamanism,” wrote Greg Hill, and it is true that Morrisseau soon began to cast himself as a shaman artist beyond the strict protocols of Anishinaabe culture.

In the summer of 1978, Morrisseau, long fascinated with the British Royal Family (he named his eldest daughter Victoria), purchased china and a silver tea set in Toronto and told his art dealer that he dreamed of hosting a Buckingham Palace–style tea party. Pollock jumped at the opportunity to market this idea and flew a group of art collectors, art critics, journalists, and friends to Beardmore for the event. Morrisseau performed the role of shaman for his guests, leading a smudging ceremony and serving blueberry tea. The party, like the exploration of Eckankar, seemed to prompt Morrisseau to engage the notion of himself as a shaman artist publicly and led to artworks that fused Anishinaabe and Eckankar teachings. It was a path Morrisseau would pursue until the end of his career.

That fall, Morrisseau was appointed to the Order of Canada in recognition of his contributions to Canadian art. He had previously been awarded the Canada Centennial Medal in 1968 and had been made a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Art in 1973, yet this honour solidified his reputation as an artist of national and international stature. An exhibition entitled Art of the Woodland Indian at the recently created McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinberg, Ontario, also included an artist’s residency at Tom Thomson’s Shack on the gallery grounds, where Morrisseau painted and also met with visitors. It was proof that Morrisseau was riding a tide and being recognized as a significant force in Indigenous art.

Solidifying His Legacy

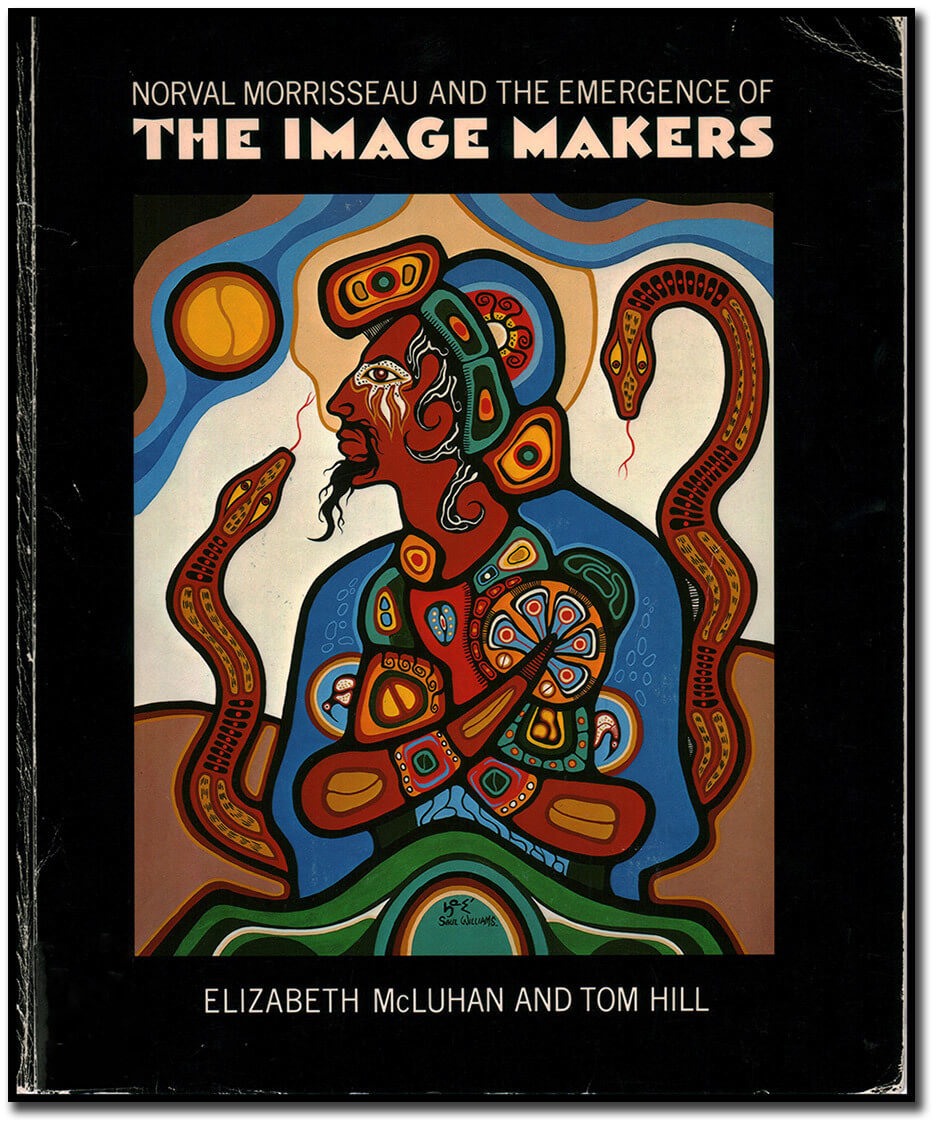

By the 1980s, it was clear that Norval Morrisseau had inspired a new generation of artists. An exhibition curated by Tom Hill and Elizabeth McLuhan in 1984 at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto placed Morrisseau’s work among pieces created by a larger group of artists, including Daphne Odjig (b. 1919), Carl Ray (1943–1978), Joshim Kakegamic (1952–1993), Roy Thomas (1949–2004), and Blake Debassige (b. 1956), who had followed Morrisseau’s lead stylistically to create their own unique expressions. The show, entitled Norval Morrisseau and the Emergence of the Image Makers, celebrated Morrisseau’s significance as an artist and a trailblazer of an artistic movement called the Woodland School. Saul Williams’s (b. 1954) Homage to Morrisseau, 1979–80, which was featured on the cover of the exhibition catalogue, clearly illustrates how important Morrisseau’s visual vocabulary was to the group.

In early 1987, Morrisseau’s work was celebrated as part of a series of group art events involving other Indigenous artists, such as Saskatchewan Cree artist Allen Sapp (b. 1928). His art also appeared in a solo exhibition in Santa Barbara, California, organized by Canadian actor John Vernon. During this time, the artist, who had been sober for a number of years, returned to drinking. In March, he was discovered living on the streets of downtown Vancouver. The press pounced on the story: for most of a month, Morrisseau was front-page news as reporters charted the ups and downs of his misfortune. When Morrisseau recovered and started painting again, the press showed little interest.

In 1989, Morrisseau was included in an important international art exhibition at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris that was organized to coincide with the two hundredth anniversary of the French Revolution. Magiciens de la Terre, curated by Jean-Hubert Martin, included one hundred contemporary artworks: fifty by Western artists and fifty by non-Western artists. It was an attempt to counteract the ethnocentric practices of most exhibitions at the time, but it has since been scorned as one of the last shows to frame Indigenous arts within a discourse of primitivism. Still, being selected for the exhibition marked a milestone in Morrisseau’s career.

For more than a decade afterward, Morrisseau, aging and suffering from Parkinson’s disease, faded from view as interest in his work waned. That changed, however, when the National Gallery of Canada mounted an exhibition of Morrisseau’s oeuvre in 2006. It was the first retrospective for a contemporary Indigenous artist ever held at the gallery, and it renewed interest in Morrisseau’s art and shifted the public’s understanding of its importance to the history of Canadian art. Because much of Morrisseau’s work was scattered in private and public collections, many Canadians had never seen his paintings, and certainly had never seen so many of his key pieces in one place at the same time. Morrisseau revelled in the attention at the openings in Ottawa and subsequent locations as the exhibition travelled in Canada and the United States. The following year, on December 2, 2007, Morrisseau died of complications related to Parkinson’s disease, leaving intact his legacy as the Mishomis, or grandfather, of contemporary Indigenous art in Canada.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements