Oviloo Tunnillie (1949–2014) was one of very few female Inuit stone carvers to achieve international success. Her decision at a young age to become a stone sculptor was an indication of her independence from artistic conventions, not only in Cape Dorset (“Kinngait” in Inuktitut) but in Canada as a whole. She created pioneering art that broke barriers with her highly personal work depicting her experiences, and her “meditations on womanhood” changed expectations about Inuit art. She was also the first Inuit stone carver to repeatedly create the nude female form. By exploring stark social realities and deep emotional expression, Oviloo both served as a role model for younger artists and addressed the devastating effects of colonialism on life and communities in the North.

Stone Carving in Cape Dorset

Stone carving was first encouraged in Cape Dorset in 1951 by James Houston (1921–2005), a young artist who had previously made buying trips to Nunavik (Quebec) camps near the present-day communities of Inukjuak (1949 and 1950) and Puvirnituq (1950). He purchased Inuit handicrafts for the Canadian Handicrafts Guild in Montreal, and the guild sold these items in annual sales held each autumn after they had been shipped to the city. Previously, most carving by Inuit for trade had been small in scale in the medium of ivory. Houston encouraged the use of stone instead of ivory, and stone carvings on offer in the November 1949 and 1950 sales caught the attention of buyers and the media.

Houston expressed his interest in turning his attention to Baffin Island, and a federal government grant to the guild financed his trip there with his new wife, Alma. They arrived in the Cape Dorset area in the spring of 1951. A few people from the camps in the region, such as Osuitok Ipeelee (1923–2005), were well known for their ivory carving, and there too Houston interested them in turning their talents to stone carving.

The Houstons remained in the Dorset area to work with the artistic male carvers and female seamstresses. By the mid-1950s the first of several deposits of attractive green serpentinite stone had been located. Increasing volumes of carvings were purchased and shipped to southern markets by the guild and the Hudson’s Bay Company. Oviloo Tunnillie’s father, Toonoo (1920–1969), was one of those who took advantage of this new economic opportunity to support their families.

A few women did create carvings from time to time, including Kenojuak Ashevak (1927–2013), who created works like Mother and Children, c.1967. But it was graphic art, not carving, that brought them to national and international attention. This trend has continued to the present day. Oviloo remains one of the few female carvers to have been associated with the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative’s activities.

Mary Qayuaryuk (Kudjuakjuk), Bird Spirit, c. mid-1960s, stone, 21.1 x 16.3 x 14.4 cm, private collection.

Oviloo Tunnillie made her first carving, Mother and Child, in 1966, when she still lived with her family several miles from the community of Cape Dorset. Her father exchanged the carving for goods available at a nearby Hudson’s Bay fur trading post. However, Oviloo did not become a full-time carver until she and her husband moved to Cape Dorset in 1972. By that time, the establishment of the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative in 1961 and the Arctic co-operative’s southern marketing agency, Canadian Arctic Producers (CAP), in 1965 had resulted in carving becoming an important livelihood for many Inuit in the area. The formation of the Co-op’s Toronto division, Dorset Fine Arts (DFA), in 1978 further expanded its marketing efforts.

The Hudson’s Bay Company store in Cape Dorset purchased lower-priced work from carvers. Oviloo, however, sold her carvings to the Co-op. They were then shipped to CAP and later DFA, which found ready markets with commercial galleries that often included Oviloo’s work in group and solo exhibitions. John Westren began working at the DFA wholesale showroom in 1984: “I was always thrilled when I was unpacking her works. . . . We tried to get those opened first because it was such a thrill to see something other than dancing bears and other common themes.” It was through a solo show at the Marion Scott Gallery in Vancouver in 1992 that the first sale of Oviloo’s work (This Has Touched My Life, 1991–92) was made to a public institution.

When Oviloo moved to the South with her family in the early twenty-first century, the Co-op would ship stone to Toronto and Montreal for Oviloo to carve, and although she continued to sell pieces through DFA during this period, she also sold directly to galleries in the city.

“Women Are Carvers Now”

Oviloo Tunnillie is one of few women to have gained national recognition as a stone carver in Canada. While it was not uncommon for women to take up carving, particularly in communities less focused on graphic art, it was men whose work gained widespread attention. Indeed, other than Oviloo, only Lucy Tasseor Tutsweetok (1934–2012) has cultivated a significant reputation with international audiences. In many ways, Oviloo’s art can be seen through a feminist lens. She was aware that her interest in carving differed from normal social roles within her Inuit culture, but she never wavered in her non-traditional role of a female sculptor. She has explained:

At one time, when I was younger, I was shy, almost embarrassed to carve. If a woman was a carver it was a very unusual thing. People would see it as man’s work, but today the woman has to be recognized more. Women are homemakers and mothers, but also women are carvers now. I want women to be strong, to try and use their talents.

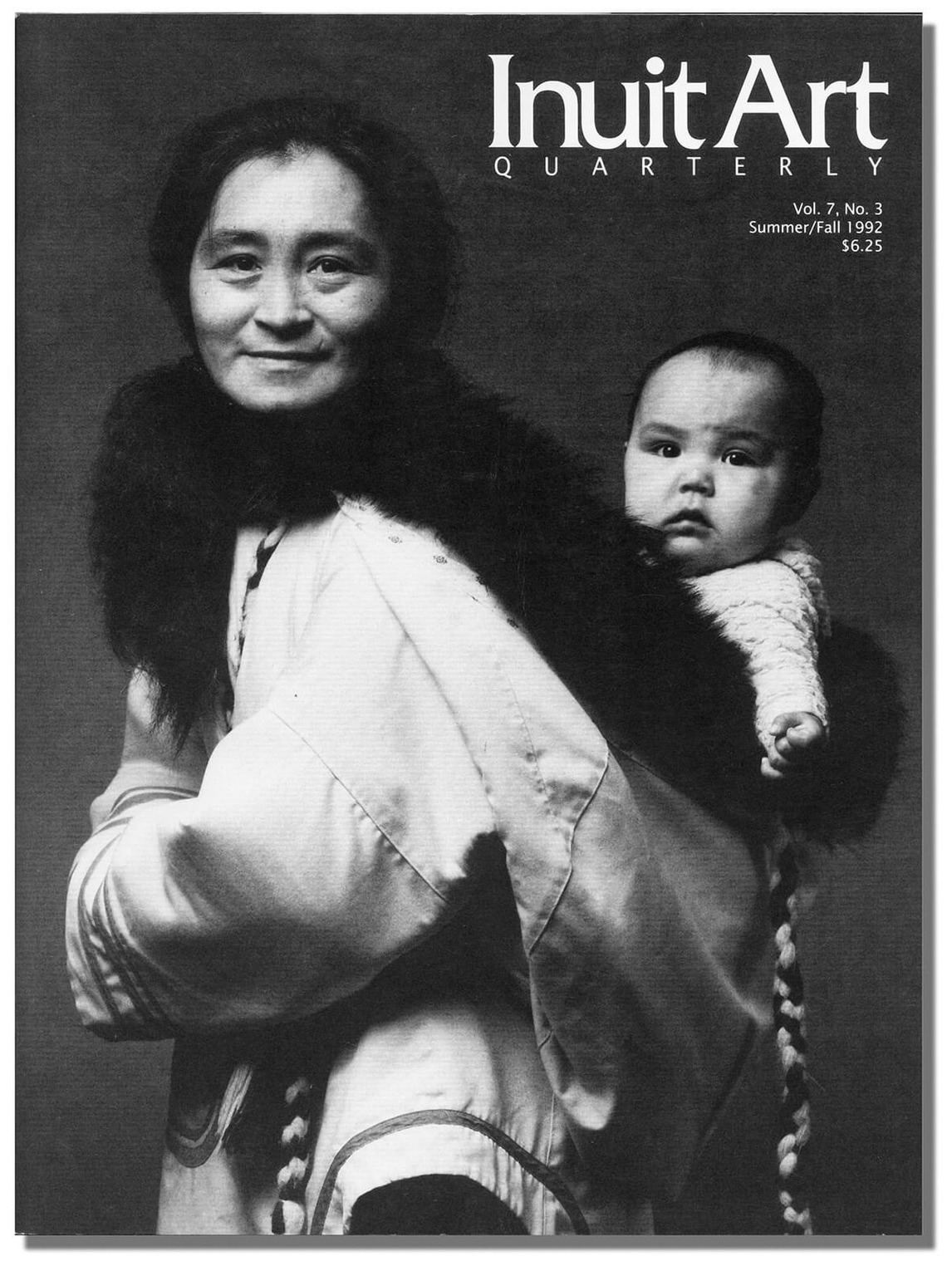

Oviloo’s role as a mother was always important to her, and she would represent her maternal relationships in carvings, blending the two aspects of her identity. For example, in 2000, she carved Self-Portrait with Daughter Alasua in 1972, depicting herself with her oldest daughter as an infant in her amautik (parka). She holds an axe in one hand and a piece of carving stone in the other. A photograph of Oviloo “packing” (or carrying) Alasua’s daughter, Tye, whom Oviloo adopted, in her amautik, taken by Canadian photographer Jerry Riley in 1990, was used on the cover of an issue of Inuit Art Quarterly in 1992. In 2002, Oviloo created a sculpture showing herself and a twelve-year-old Tye proudly holding the framed photograph by Riley (Oviloo and Granddaughter Tye Holding Photo by Jerry Riley).

In sculptures Oviloo acknowledged women family members who were also artistic: her mother, Sheokjuke (1928–2012), in the self-portrait Woman Showing a Drawing, 2006; and her husband’s grandmother, Ikayukta Tunnillie (1911–1980), in Ikayukta Bringing Drawings to the Co-op, 2002, and Ikayukta Tunnillie Carrying Her Drawings to the Co-op, 1997. Even her sister Nuvalinga appears in My Sister Nuvalinga Playing Accordion, 2005. Despite some similarities with late work by graphic artist Napachie Pootoogook (1938–2002), this degree of specificity about family and relationships has been rare in art by Inuit.

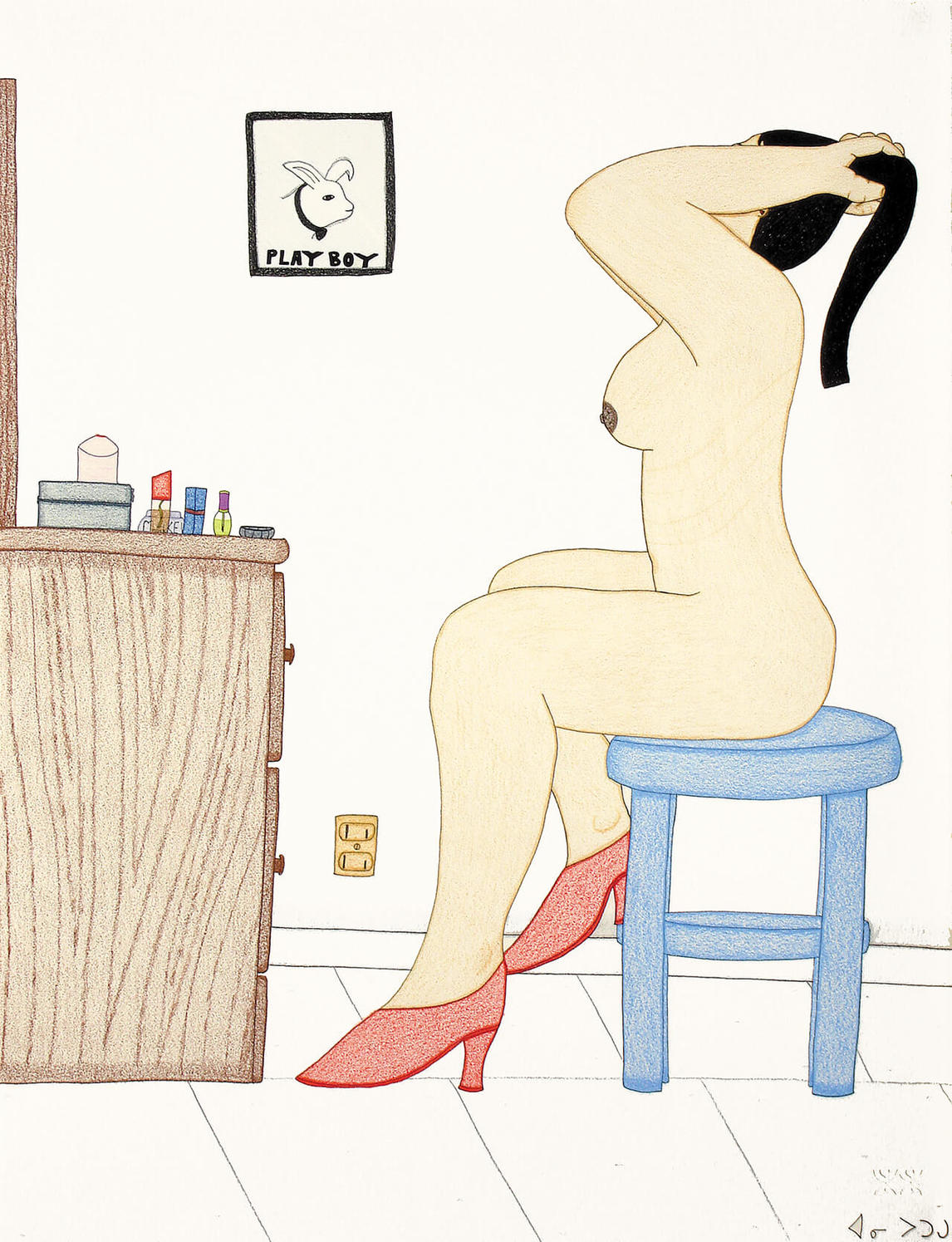

Many of Oviloo’s female figures are even more unconventional. They wear culturally unspecific robes, or they are nude. Oviloo is the first Inuit stone carver to repeatedly create the nude female form, in works such as Woman in High Heels, 1987. In 1992, Oviloo stated, “My favourite work is on Taleelayu—women figures.” Her depictions of the sea spirit Taleelayu, or Sedna, are strong, voluptuously nude women with whale flukes instead of legs. They were not inspired by a desire to tell the sea spirit’s story but are expressive presentations of the female body. In Diving Sedna, 1994, wet hair flows sensuously around full breasts.

Other sculptures by Oviloo draw on everyday experiences of the body, such as Nature’s Call, 2002, which depicts a woman on a toilet with her pants around her ankles. Untitled (Masturbating Woman), 1975, expresses a frankness toward sexuality that is seldom seen in the work of Inuit artists. Thomassie Kudluk (1910–1989), a carver from Kangirsuk, Nunavik, became known for his humorously sexual carvings in the 1970s, but drawings by Inuit women have more frequently been the means to express intimate subject matter.

In recent years, Shuvinai Ashoona (b.1961) has become known internationally for her uniquely surreal, sometimes sexual imagery on large sheets of paper. Napachie Pootoogook’s work from the 1990s explored themes seldom seen in Inuit art: eroticism, domestic violence, and gender relations. Annie Pootoogook (1969–2016) also used the more personal medium of drawing on paper to express an unvarnished portrait of modern-day life in Cape Dorset. Oviloo and Annie have served as role models for a younger generation of artists, such as Jamasie Pitseolak (b.1968), to address personal themes involving sexual abuse and modern technology.

Tuberculosis and the Treatment of Inuit Patients

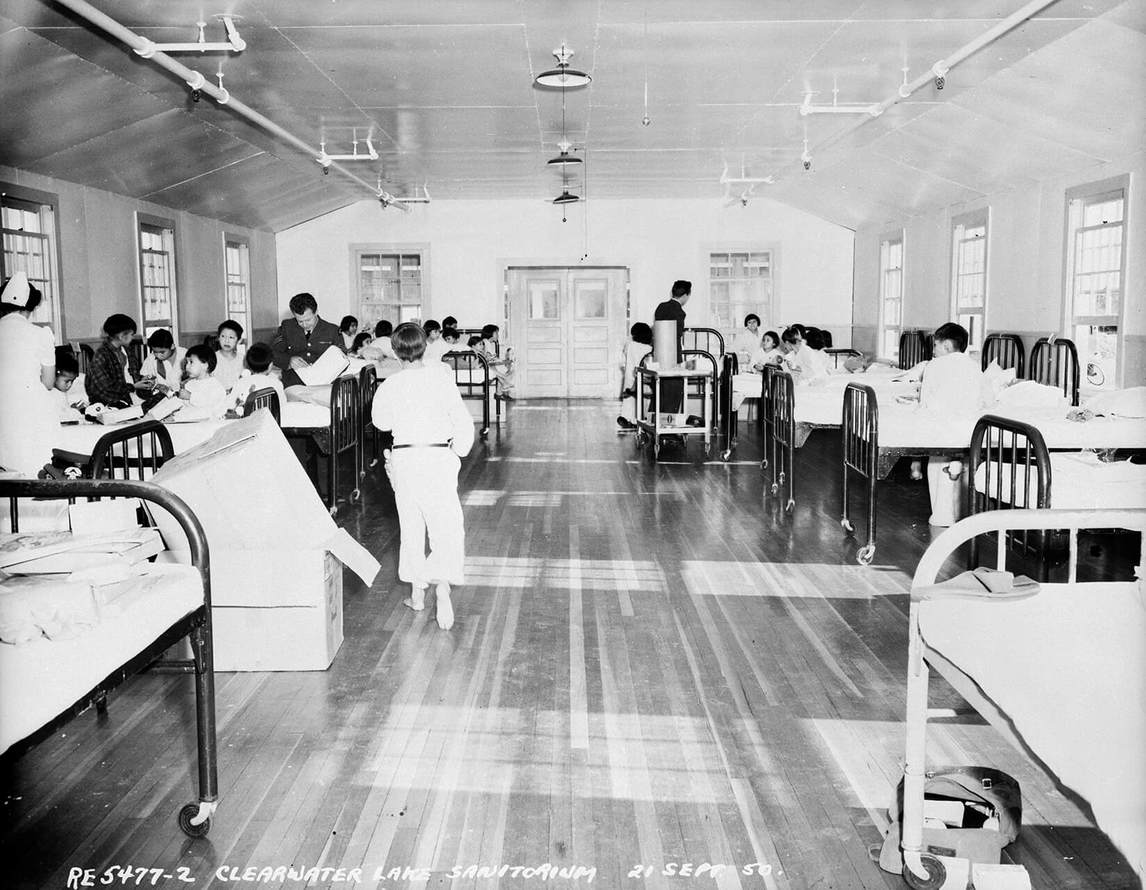

Oviloo Tunnillie’s carved memories from the three years she was in southern hospitals in the 1950s form a powerful personalized account of the colonial treatment of Inuit and other Indigenous people at that time. So-called Indian hospitals were racially segregated facilities used to isolate Indigenous tuberculosis (TB) patients because of a fear among health officials that “Indian TB” posed a danger to the non-Indigenous population.

Oviloo’s work became increasingly autobiographical in the 1990s. This shift was heralded by a major sculptural grouping of figures, This Has Touched My Life, 1991–92, which reveals a memory from her time at Clearwater Lake Sanatorium, near The Pas, Manitoba. While at the hospital, she was taken by automobile to see two women whose faces were covered by veils, as was fashionable in the 1950s. She had no idea why or where she was going. Her description of this experience reveals that it was quite surreal for her:

When I saw these two, I really noticed the way they were dressed and their faces were hidden. Well, I could see them but they were unrecognizable as they wore hats that had lace pulled down in front of their faces and they each had purses. . . . [H]aving seen them like this has been most memorable for me. I have not met any white person such as these two yet. I wonder sometimes if they were ashamed of their faces because I’ve never seen that before.

Several of her other hospital works, such as Nurse with Crying Child, 2001, and Self-Portrait at Manitoba Hospital (Holding Teddy Bear), 2010, are poignant self-portraits. A third hospital piece, Oviloo in Hospital Bed, c.2000, is more wrenching in its raw emotion, as Oviloo screams while tied to her hospital bed.

In 1945 the federal Department of National Health and Welfare took over the building and running of hospitals. From the nineteenth century onward, Inuit populations had been afflicted by various diseases brought by European settlers and missionaries. Tuberculosis moved slowly, but by 1950 increasing numbers of people became infected with the highly contagious bacterium. The federal government began a large-scale operation to reduce the occurrence of the disease in northern populations, run under the auspices of the Advisory Committee for the Control and Prevention of Tuberculosis among Indians. This included surveys of infection as well as forcible removal and confinement of those infected. The federal government made the choice not to build hospitals in the North but to evacuate infected individuals to the south of Canada and invest in facilities there.

Part of the national operation were ships dedicated to carrying TB-infected passengers from northern Canada to southern sanatoriums. One such ship was the C.D. Howe, which ran from 1950 to 1969. It was specially fitted after 1946 with medical facilities quarantined away from crew quarters. The ships were equipped with X-ray technology to diagnose infections, and patients were marked on the hand with identifying numbers and the results of their tests.

Children, even infants, who were diagnosed with TB would be taken from their parents and sent to the South. Men and women were forced to leave their families behind. In 1953, the Indian Act was amended to include the Indian Health Regulations that made it a crime for an Indigenous person to refuse treatment or to leave a hospital before being discharged.

Inuit evacuees were sent to hospitals with staff who did not speak Inuktitut. Patients who were treated by strict bedrest were sometimes tied to their beds, as in the sculpture Oviloo in Hospital Bed, c.2000. Oviloo also suffered sexual abuse while in the hospital. In 1993 she powerfully expressed the theme of a helpless, violated woman in a small carving, Nude (Female Exploitation). Typically for the artist, expressive hands communicate her inner emotional state: one to her groin and another to her anguished face. The work was referenced by Oviloo to Adrienne Clarkson in 1997:

This one has to do with child molestation. I have gone through that experience with medical personnel when I was a little girl. Even though it wasn’t actual rape, I was violated sexually. We know that doctors can do anything with your body. And myself when I was a little girl, doctors worked with me but not all doctors are good. I’ve had an experience with doctors that did what they shouldn’t have been doing, so that’s the meaning behind this carving—that it shouldn’t be this way.

Oviloo Tunnillie, Nude (Female Exploitation), 1993, serpentinite (Kangiqsuqutaq/Korok Inlet), 7.8 x 35.8 x 13.8 cm, signed with syllabics, private collection.

In the 1950s tuberculosis treatment began to change from months and years of bedrest to lung surgery and finally to antimicrobial medications. Provincial sanatoriums emptied as outpatient treatment became the norm. However, treatment for Indigenous patients was different. They were kept in hospitals for years as they were not considered capable of managing their recovery at home as were non-Indigenous patients. Many Indigenous patients died and were buried near treatment facilities without any notice sent to their families informing them of their deaths. Cape Dorset artist Pitaloosie Saila (b.1942) was kept in southern hospitals from 1950 to 1957. Unlike Oviloo, Pitaloosie and other artists with similar experiences did not represent those in their artwork.

Slaughter of Sled Dogs

Social issues reflective of colonial attitudes recur in Oviloo’s work, from relationships with southern communities to policies that profoundly affected Inuit life in the North. One issue that emerged in Oviloo’s sculptures early on was the slaughter of qimmiit, or sled dogs, which occurred on Baffin Island and in Nunavik from the mid-1950s to the late 1960s. For example, Oviloo’s sculpture Protecting the Dogs, 2002, reveals her knowledge and concern about the slaughter of sled dogs in south Baffin Island. According to her husband, Iyola Tunnillie, this work depicts a man known in Cape Dorset for trying to protect his sled dogs from being shot.

For generations, Inuit and their sled dogs lived and hunted together. Dogs provided the only means of transportation in winter and on land in summer. Their other uses were vital: they sniffed out seal holes and avoided ice cracks in fog and darkness. During blizzards, dogs could track scents to follow paths. They could surround polar bears for the hunter’s spear or rifle or ward them off, as in Oviloo’s carving Dog and Bear, 1977.

Dogs were the only animals Inuit named individually. Children were given puppies to raise, and young Inuit boys, once they had a small team of their own, were taken seriously as men. Dogs were an important part of Oviloo’s life and she always had them as pets. They were part of Oviloo’s family group in the sculpture Family, 2006. They are the main subject in the complex composition Dogs Fighting, c.1975.

The slaughter of sled dogs took place over twenty years. They were killed at different times by different people, mainly the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. A range of different reasons motivated the killings (e.g., fear of diseases such as distemper), but the main effect was to prevent Inuit from keeping dogs when they were living in places where there were many qallunaat (non-Inuit). It remains a particularly painful and controversial topic for Inuit. It was the subject of a report published by the Qikiqtani Inuit Association in 2014, as well as a 2010 documentary film, Qimmit: A Clash of Two Truths, directed by Joelie Sanguya and Ole Gjerstad.

Substance Abuse

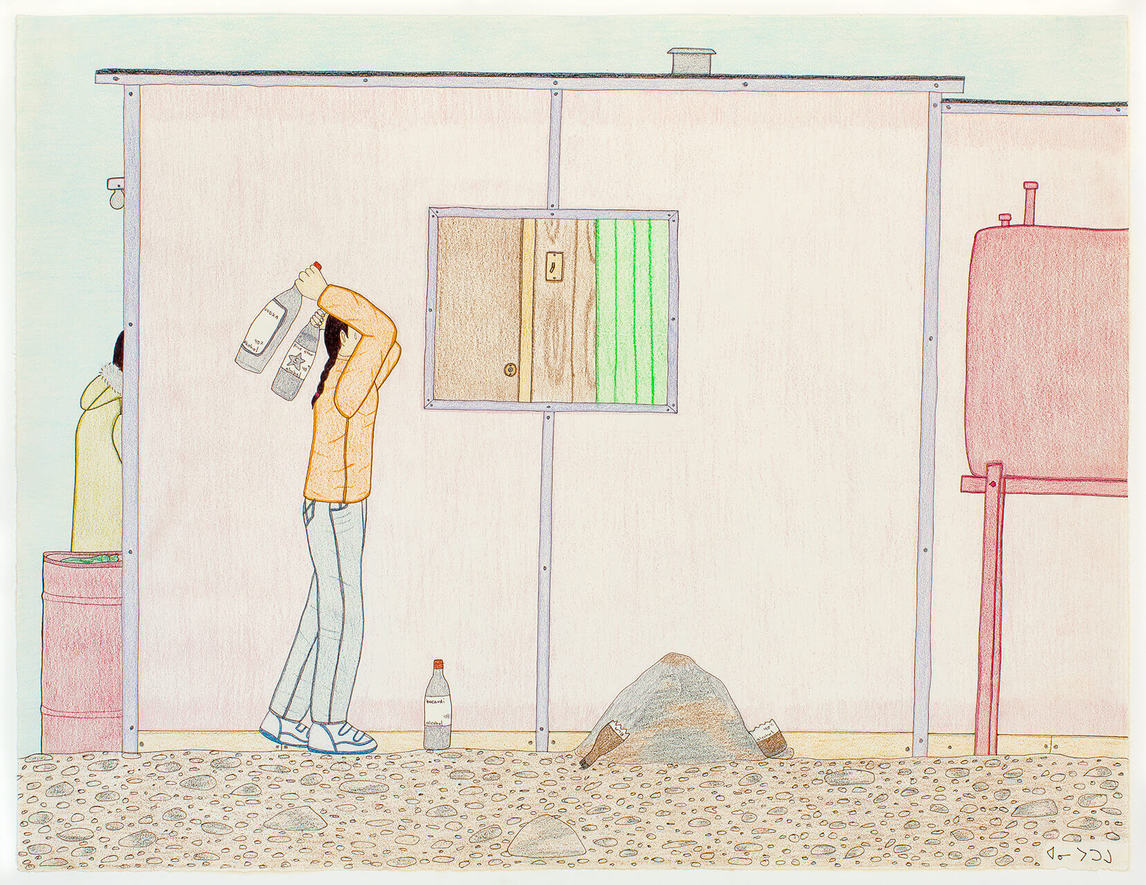

Oviloo Tunnillie clearly recognizes the effects of colonization, and her critiques of alcoholism are as pointed as when she references the displacement of tuberculosis patients and the eradication of sled dogs.

In 1980 Oviloo carved Thought Creates Meaning, a surprising composition inveighing against the evils of alcohol and its effects on Inuit:

The hand represents the grip of drink on Inuit. . . . Inuit were given alcohol by the government. The hand, which is a symbol of Inuit, is pointing a finger at the government official. No one in particular, but qallunaat [non-Inuit]. You will notice the man isn’t wearing kamiit [skin boots] because the person’s white. . . . The liquor was brought up by the white people, not by Inuit. This was my thought at the time. I disliked alcohol for what it can do to people.

Another powerful sculpture, Woman Passed Out, 1987, reveals the artist’s concern about alcohol abuse, as well as its disastrous effect on a vulnerable woman:

This is a drunken person that tempted the others to drink more. This person is passed out, because the alcohol can make you do anything, like this one. A woman doesn’t mean to be the way she is here . . . but it happens after she has had too much to drink.

In the 1997 television episode “Women’s Work: Inuit Women Artists” of Adrienne Clarkson Presents, Oviloo commented further:

And this carving I did, I know that you shouldn’t be treating a woman this way and this man had been drinking with this woman. The woman is helpless.

Oviloo’s forceful commentary on the issue of substance abuse is unconventional for an Inuit artist. Rare examples by other artists are Annie Pootoogook’s drawing Memory of My Life: Breaking Bottles, 2001–2 and Manasie Akpaliapik’s (b.1955) 1991 sculpture Untitled that appeared on the cover of Inuit Art Quarterly in 1993. His carving was of a man’s head shattered by an embedded bottle of alcohol. Oviloo dealt with the debilitating effects of alcoholism in her own extended family, which was possibly related to the murder of her father and the suicide of her daughter as well as of her niece, the daughter of her sister Nuvalinga. Substance abuse and suicide are the two most serious social concerns in Inuit communities today.

Revelations of Grief

Few of Oviloo Tunnillie’s contemporary Inuit artists addressed inner emotional states and grief, which made her work unique. Other artists of her era—for example, Osuitok Ipeelee (1923–2005) and Kiugak Ashoona (1933–2014)—most typically favoured depictions of Arctic animals, domestic and hunting scenes, the sea spirit Taleelayu, shamanic transformations, and episodes from well-known legends and stories.

Oviloo Tunnillie, Oviloo and Toonoo, 2004, serpentinite (Kangiqsuqutaq/Korok Inlet), 22.2 x 20.3 x 24.1 cm, signed with syllabics, collection of Barry Appleton.

Human figures were impersonally dressed in culturally explicit fur clothing and were engaged in activities relating to pre-settlement living. Depictions of single human figures were rare and unemotionally engaged in an implied activity. Women were usually shown in their maternal roles with a child or children. The deep emotional expression conveyed in Oviloo’s work, as in such sculptures as Repentance, 2001, transcends the cultural or traditional while also speaking deeply to the artist’s own experiences.

The tragic episode of the death of her beloved father, Toonoo , must have contributed to Oviloo’s several self-portraits of grieving women. In 1969 Toonoo was shot to death by Mikkigak Kingwatsiak, the husband of Toonoo’s daughter Nuvalinga, in what was believed at the time to be a hunting accident. This shock re-emerged twenty-five years later when Mikkigak confessed to murdering Toonoo. Grief at her father’s death is the subject of Oviloo and Toonoo, 2004, in which the memory of him appears as a small figure that seems to be trying to reach his weeping daughter from a distance.

In her work, Oviloo also addressed the suicide, in 1997, of her thirteen-year-old daughter, Komajuk. Mental anguish is expressed in a number of Oviloo’s sculptures from this date on, beginning with Grieving Woman, 1997. In 2000, she created a nude and vulnerable Crying Woman, her face buried in arms folded on knees drawn up into herself. In both of these, covered faces cut the figures off emotionally from the outside world and create focused images of isolation and sadness.

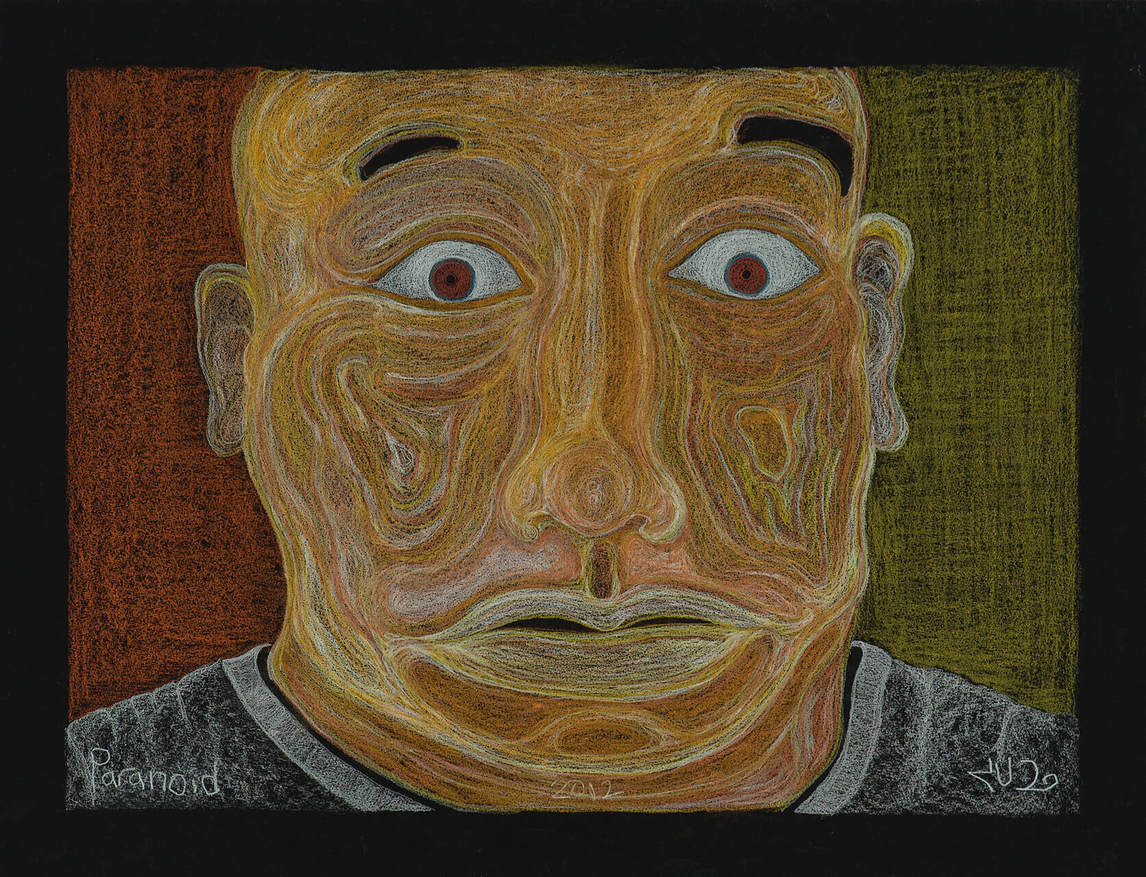

The unorthodox expression of inner states of mind was also a powerful feature of the graphic art and sculpture of Oviloo’s brother Jutai Toonoo (1959–2015), who may have been influenced by his sister. Both artists uniquely created human forms and figures devoid of a narrative context. Jutai’s non-narrative images of human heads and figures, such as Paranoid, 2012, are deeply personal and often portray restless sleep or dreamlike states. A bipolar disorder influenced his fierce independence from conventional subjects. Both he and Oviloo created their unique imagery in a community that had deep roots in culturally specific and narrative art forms.

Oviloo Tunnillie, Woman Covering Her Face, 2000, stone, 37.2 x 14.6 x 7 cm, collection of Jane Ross.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements