The life of Annie Pootoogook (1969–2016) tells an important national story, and her career marks a pivotal shift in the national consciousness around contemporary Inuit art. With a keen eye for detail and fearlessness in representing daily life—the celebratory, the frightening, and the mundane—she captured the attention of Southern audiences. Although imported culture and technologies have dramatically changed Inuit life, the North has also stayed true to tradition: community, food, and language remain sources of Inuit pride. In her drawings, Annie depicted what is still valued and unique in her culture and what is changing rapidly. She had a meteoric rise in the art world that was tragically cut short when she died in 2016.

Early Life

A member of the Pootoogook clan, Annie was the daughter of Napachie Pootoogook (1938–2002) and Eegyvudluk Pootoogook (1931–2000), and was a third-generation artist. She was born in 1969 in Kinngait (Cape Dorset), Nunavut, an isolated hamlet on Dorset Island off the southern coast of Baffin Island (Qikiqtaaluk). Kinngait, an Inuktitut name that refers to mountains, is home to one of the most important centres of art production in Canada, the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative; its art division is now known as Kinngait Studios. Both of Annie’s parents were artists working with the Co-op, and her grandmother, the renowned artist Pitseolak Ashoona (c.1904–1983), and uncle, Kananginak Pootoogook (1935–2010), were also accomplished artists. In the 1970s, at the height of her career, Pitseolak’s work was known throughout Canada and abroad, while Kananginak was a critical early leader at the Co-op. Annie grew up surrounded by artists, many of whom would be important influences when she began her own work as a professional artist.

Annie was the third youngest in a family of ten children. Her brother Goo Pootoogook (b.1956), the family’s eldest child, also became an artist and still resides in Kinngait. Shortly before Annie’s birth, her brother See and sister Annie died in a house fire. According to custom, Annie shares the same name as her deceased sister. Janet Mancini Billson and Kyra Mancini have noted that for Inuit, an important naming practice “involves passing on the name(s) of recently deceased community members to the next newborn, regardless of gender.” Also following this tradition, the first boy born after the accident was named Cee (also spelled See). Today Cee Pootoogook (b.1967) is an artist and printer at Kinngait Studios.

Another daughter, Kudluajuk, drowned in 1972 as a young child, swept away by a wave as she was playing on the shore. Despite these tragedies, family members recall a relatively happy childhood featuring trips to the land for clam digging, berry picking, and camping. Annie attended primary school in Kinngait and was a bright student. Later she travelled to Iqaluit for four years of high school, as there was no high school in her community. It is uncertain whether she graduated. Her cousin, the artist Siassie Kenneally (1969–2018), recalled spending time together with Annie and noted that she was very social.

Artistic Training

Following high school, Annie spent time in Nunavik (Northern Quebec) before returning to Kinngait in 1990. At first Annie had difficulty finding a job in Kinngait. Given her artistic lineage, however, it was only natural to assume that she would try her hand at drawing at Kinngait Studios, where many of her family members and members of the community worked and socialized each day while creating art to be sold in “the South.” Kinngait boasts more artists per capita than any city in Canada—the result of a federal government program established in the 1950s with the intention of creating a cash economy in Inuit communities.

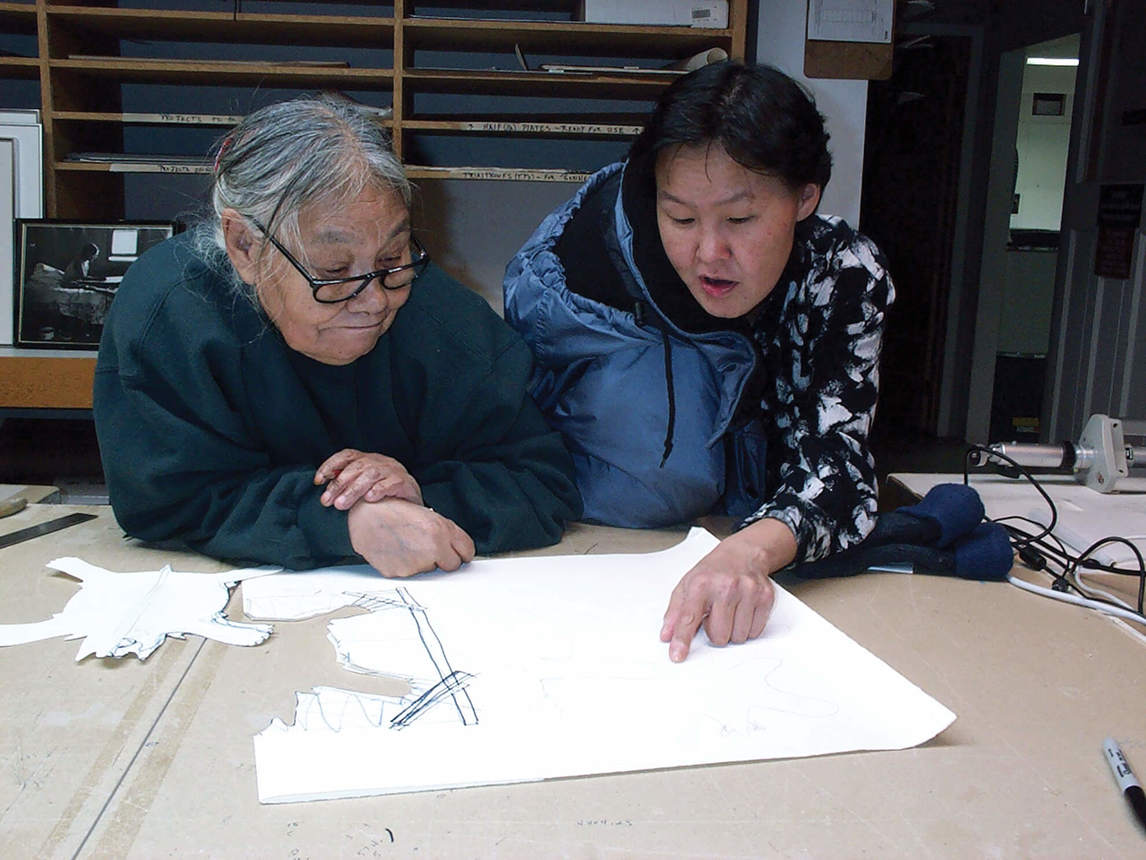

In 1997 Annie finally began drawing regularly. She honed her skills by working alongside the Elders at Kinngait Studios. In an apprenticeship-style system, she learned by observation and through the back-and-forth of critique and camaraderie among the younger and less experienced artists. They would watch and imitate the senior artists while they worked on developing their own individual styles, which were based on the precedents established by the Elders. Annie understood the purpose of this training; drawing was a way to provide an income for herself. She was encouraged by the Elder women in the community, including her mother, Napachie Pootoogook. Once she gained enough confidence, Annie picked up paper from the studios and began to make her first drawings at home. Then she made it a daily ritual. Each day she would work at the studio with focus, intent, and a drive to represent something new.

William (Bill) Ritchie (b.1954), the manager and supervisor of Kinngait Studios and the printers, offered support and encouragement. He found her “engaging, and kind of hip and cool” and “smart as a whip.” In reflecting on her development as an artist, he noted, “At times she was uninterested and at other times she was keen. She learned to listen to advice, grew with praise and cash incentives, [and] took on the large paper challenge that everyone goes through.” To Annie, as to the other artists, Kinngait Studios offered a supportive environment in which she could work and sell her drawings weekly, permitting her to be self-sufficient but not burdened with the business of selling her own art. There Annie found purpose and independence.

Rapid Rise

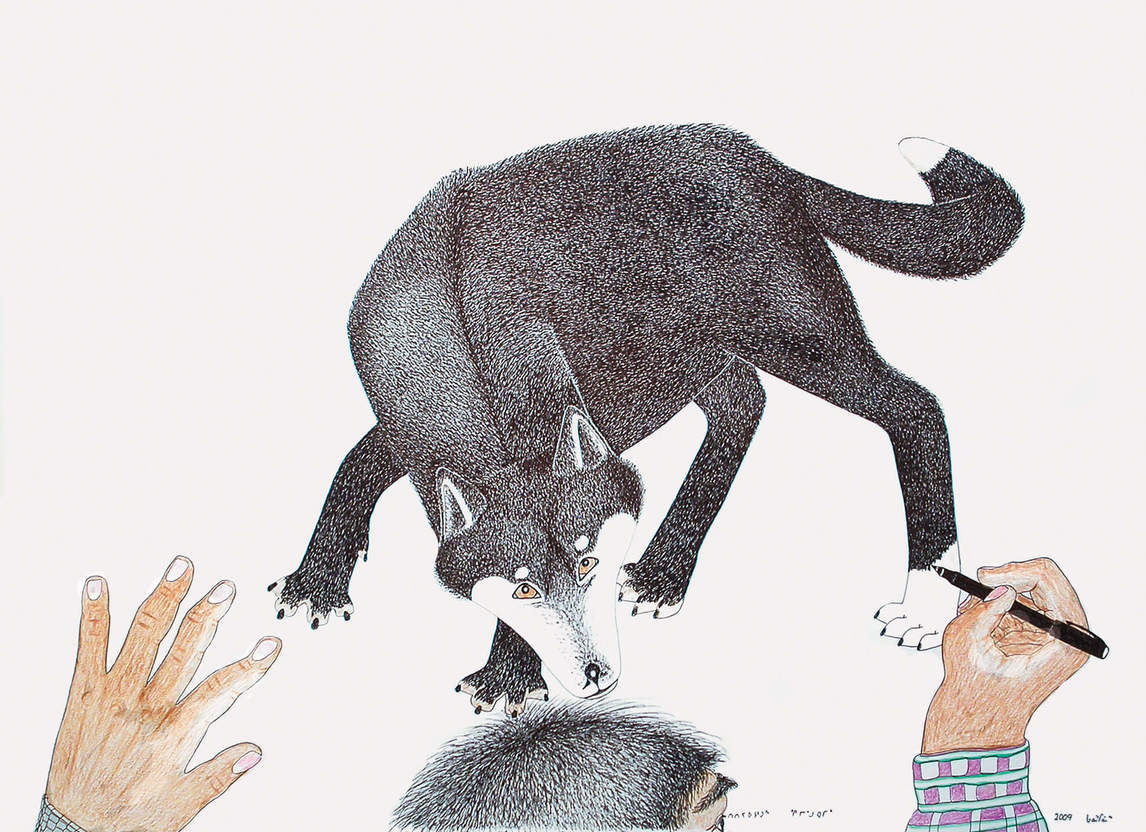

Annie’s early drawings showed promise, and the more she drew, the more sophisticated her work became. For instance, Pitseolak Drawing with Two Girls on Her Bed, 2006, reveals her interest in experimenting with perspective. Her work also followed the path laid down by her grandmother, Pitseolak Ashoona, and her mother, Napachie Pootoogook, who created original autobiographical works that inspired her from a young age. Both Pitseolak and Napachie were highly observant and their profound insights were reflected in their works. Commenting on Napachie’s drawings, Darlene Coward Wight noted that they “are filled with details that give a realistic portrait of the culture of the Inuit of south Baffin Island, or the Sikusilaarmiut: the clothing, hairstyles, tools, summer and winter dwellings, and the landscape setting.” Annie was similarly gifted in capturing the nuances of her environment.

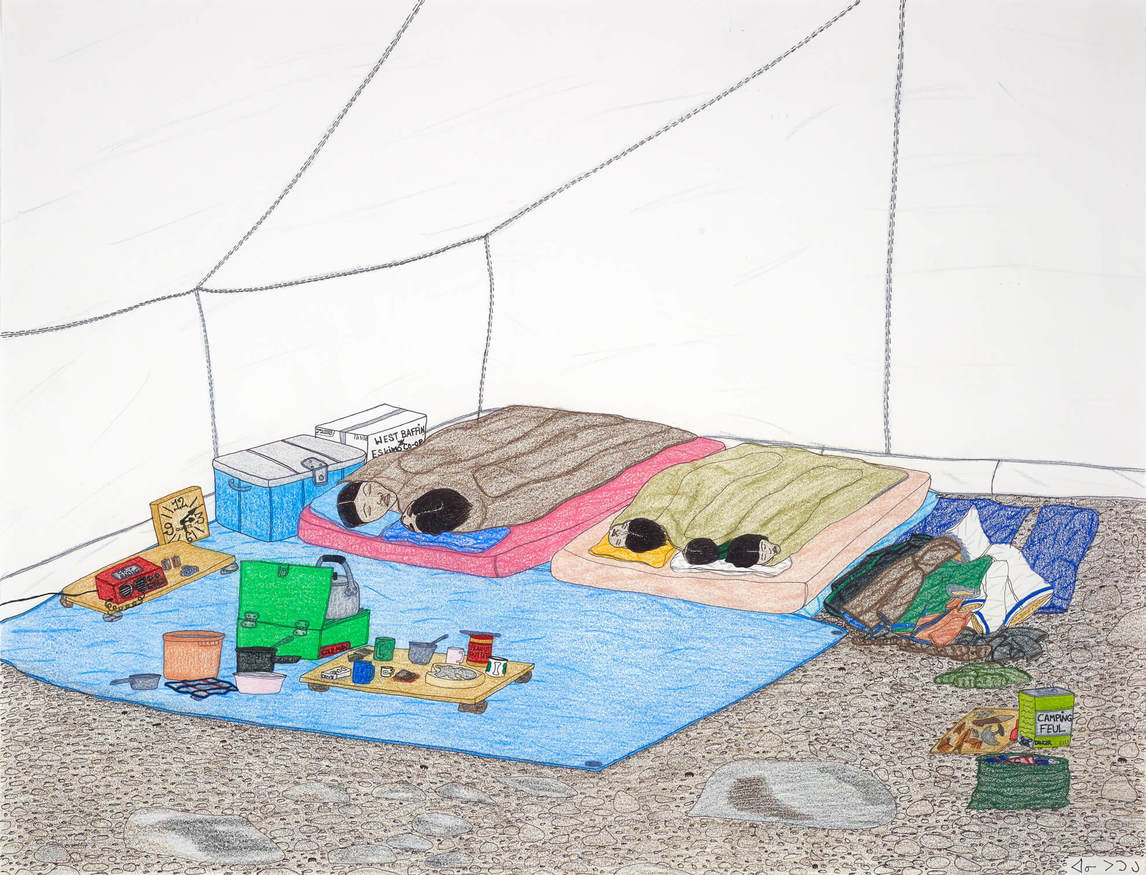

Annie Pootoogook, In the Summer Camp Tent, 2002, coloured pencil and ink on paper, 51 x 66 cm, Collection of John and Joyce Price.

As early as 1997 her drawings caught the eye of Jimmy Manning, who was then an art buyer at the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative. Many of the artists working at the Co-op, though, had their doubts. Annie’s drawings did not visually reflect the most prominent prevailing aesthetics and themes at the Co-op at that time, which were primarily scenes from nature or stories from Inuit mythology, subjects that appealed to buyers in the South. Instead, her work reflected the modern life of a young woman living in a consumer society. Some questioned whether this work would ever sell.

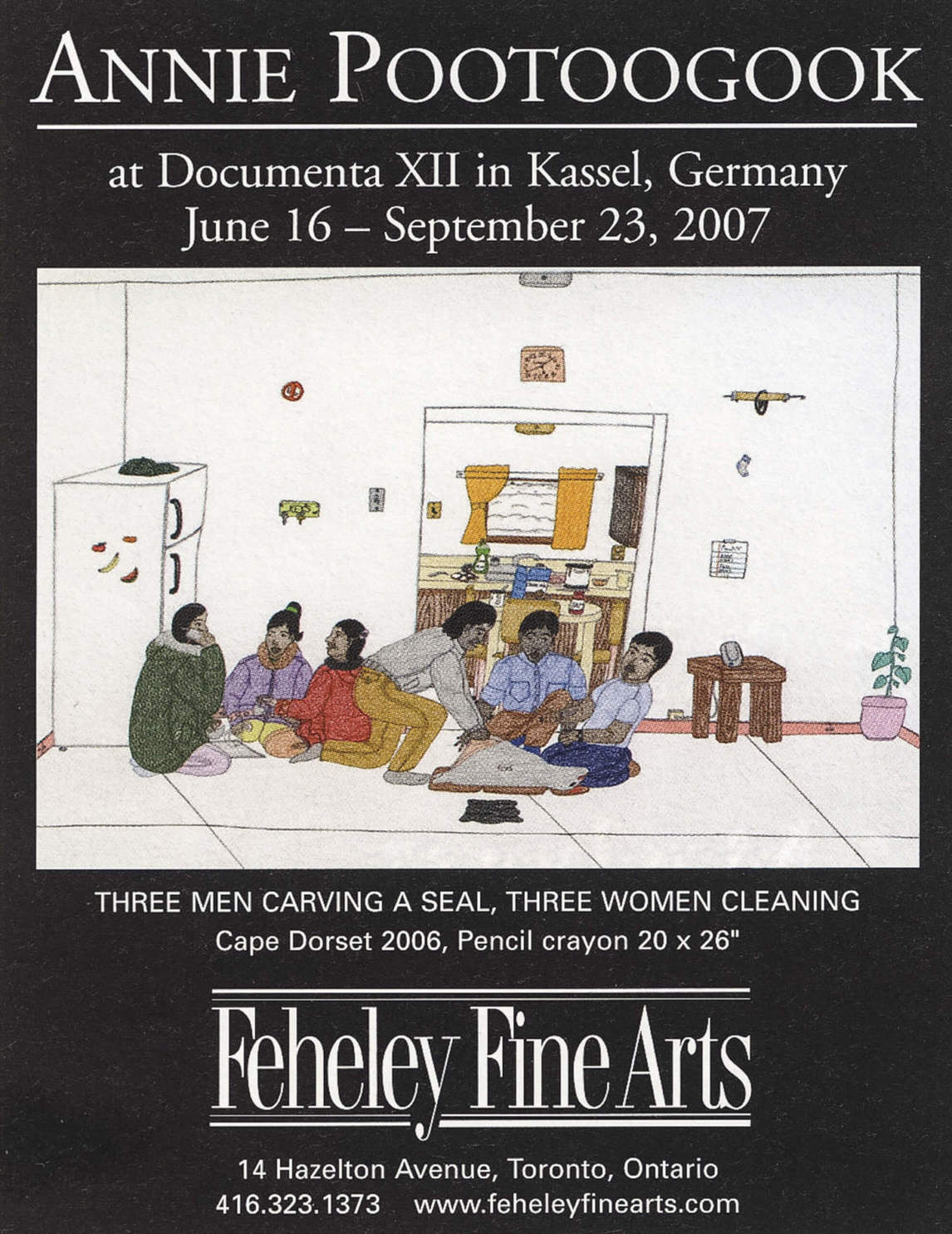

The answer soon came in the competitive art market of Toronto. In 2000 a group of Annie’s drawings were brought to Dorset Fine Arts, the Toronto marketing arm of the Co-op. This showroom distributes drawings, prints, and sculptures created in Kinngait to sellers throughout the world. Annie’s drawings were brought to the attention of art dealer Patricia Feheley, owner of Feheley Fine Arts in Toronto, by Manning, who suggested she take a look at this new artist’s work. Feheley writes: “I…was stunned. Both the imagery and the direct style were so unusual and arresting. Although the Inuit Studio manager told me that I would never sell them, I asked for six to be shipped immediately.”

As a result of Feheley’s interest, Annie was included in a 2001 group exhibition at Feheley Fine Arts titled The Unexpected, highlighting emerging artists from Kinngait. “People would gravitate automatically to her drawings,” Feheley recalls. The commercial success of this showing prompted Annie’s first solo exhibition at the gallery: Annie Pootoogook—Moving Forward: Works on Paper was held in 2003. Many who visited the gallery were captivated by Annie’s drawings, which included works such as My Grandmother, Pitseolak, Drawing, 2001–2, and Preparing for the Women’s Beluga Feast, 2001–2. Highly original in content and execution, her work was contemporary while also part of a long trajectory. As the exhibition catalogue noted, her drawings included an enormous range of references to twenty-first-century life in the Arctic, from televisions to community institutions, all of which shaped “northern reality and are as much part of the fabric of Annie’s world as the dog sleds and skin clothing of Pitseolak’s drawings were part of Arctic life in the mid-twentieth century.” A few astute collectors bought out the show.

Writing about Annie’s work shortly after her first solo exhibition, Feheley reflected on Annie’s interest in how television news enters people’s awareness in the North as persistently and obsessively as in the South:

It is not unprecedented for contemporary Inuit artists, particularly those of the younger generation, to create images inspired by current global events. Oviloo Tunnillie has created sculptures of praying or grieving women as a stated response to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in New York City. Other artists, including Kavavoaw Mannomee [Qavavau Manumie], have responded with graphics depicting planes crashing into buildings. Annie was not immune to the impact of this seminal moment, and has revisited the theme in her own recent drawings. She explains that Cape Dorset was inundated with news on the radio and television leading up to and during the [Iraq] war [of 2003], and the subject came to dominate local conversation and daily life in the North, as elsewhere…. In many ways Annie’s images of the TV news footage of the war are most poignant as they reveal the literal “window on the world” created in contemporary Inuit homes by modern media.

Annie became well known for her work on “contemporary Inuit homes,” and she quickly won the support of a group of tenacious curators and directors that included Wayne Baerwaldt, Reid Shier, and myself at The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto, and Christine Lalonde at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa.

In 2006 The Power Plant held a solo exhibition of Annie’s work, simply titled Annie Pootoogook, which I curated. The Power Plant is dedicated to exhibiting Canadian and international contemporary art, and showing Annie’s drawings in this space significantly elevated her profile as an emerging Inuit artist creating a compelling body of work. It brought her work to a much larger public than a commercial gallery could have done, and Annie travelled to Toronto to attend the opening.

National attention soon followed. Reviewers, including Murray Whyte, writing for the Toronto Star, and Sarah Milroy, at the Globe and Mail, saw The Power Plant show as a fascinating exhibition, and an important one. As Whyte later observed, “The Power Plant’s landmark 2006 show, of Annie Pootoogook’s frank drawings of contemporary northern life, marked the first time Canada’s pre-eminent contemporary art venue had held a major show by an Inuit artist.” The rave reviews helped direct the awareness and interest of collectors of contemporary art to the new work being done in the Canadian Arctic.

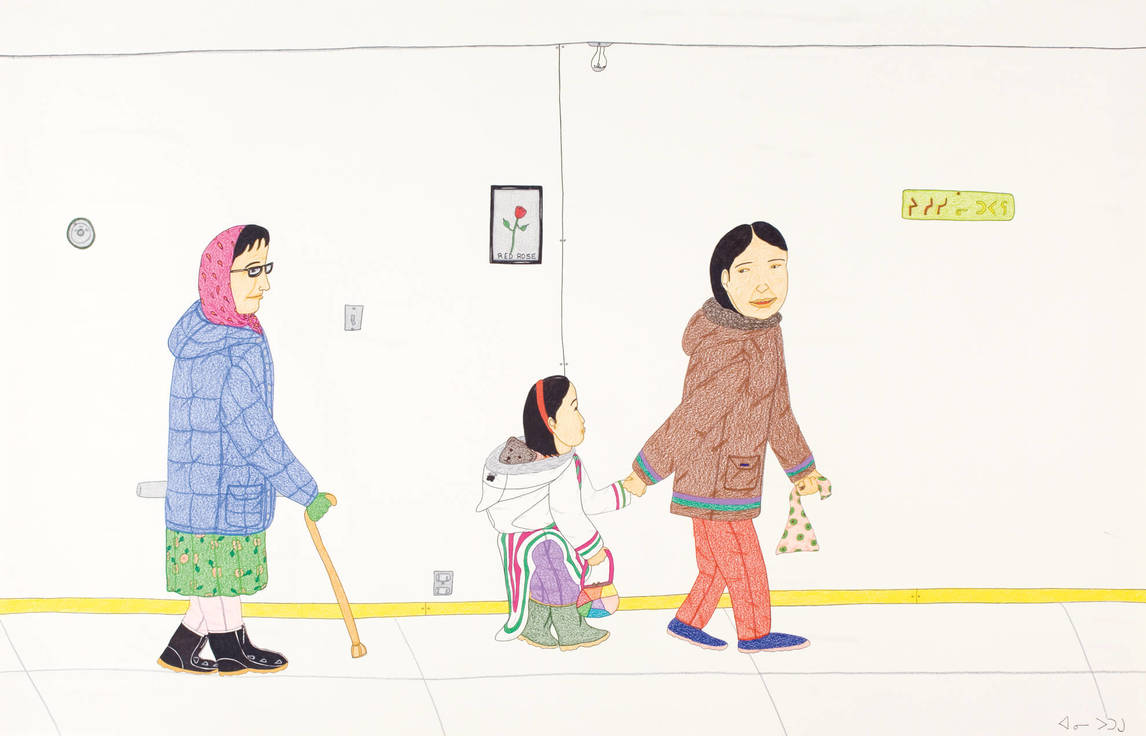

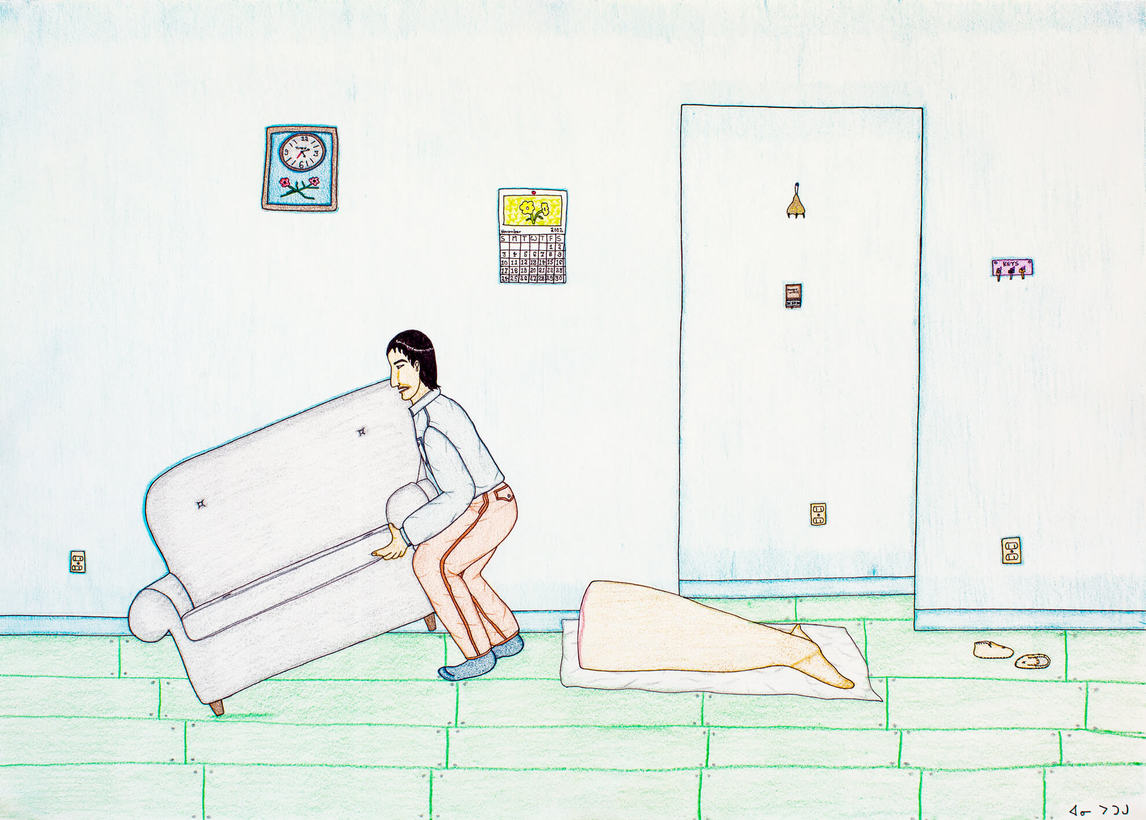

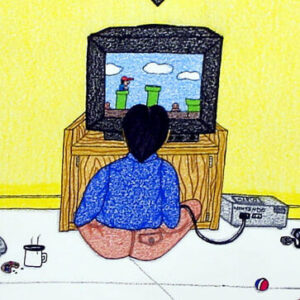

Annie’s images challenged viewers’ expectations. Visitors to The Power Plant discovered an Inuit artist who not only displayed original pictorial skill but also created content that spoke to them. Annie’s drawings are narrative based. They record, or reflect on, the activities of her daily life, such as camping, doing her hair, and watching television. Although she sometimes depicts objects with symbolic or emotional properties, such as her grandmother’s glasses, Annie does not idealize the domestic-interior spaces that she represents. The contents of these spaces can be surprisingly banal. She belonged to the first generation in the North to have regular access to television, and many of the drawings shown at The Power Plant contain references to popular media topics of the time, ranging from the on-screen chaos of The Jerry Springer Show to the ongoing Iraq War and the hunt for Saddam Hussein. Some drawings opened a window onto the cycles of addiction and abuse found in the lives of some members of her community. For Annie, there was no mythic vision of the North.

Annie’s exhibition at The Power Plant signified a shift in how contemporary art was understood as well as in how Northern art was received. The presentation of Annie’s work in a contemporary art gallery signalled that it was time to drop the pretense that artists working outside the Eurocentric mainstream are automatically locked into ethnic or regional categories of artmaking. Eurocentric beliefs are central in producing problematic, preconceived notions of what Inuit art “should be,” and Annie’s art refused to conform to these conceptions. As Gerald McMaster notes, “Pootoogook’s austere, often humorous pencil-crayon drawings are relentless in capturing the changing conditions of life in the North. Tradition often comes up against modernity.” By confronting Southern audiences with the trappings of contemporary life such as television, video games, and store-bought foods, her drawings reveal a reality rooted in cultural practices specific to the North yet tempered by symptoms of everyday life that any consumer of mass media could relate to.

Global Recognition

In 2006, after the success of the exhibition at The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery, Annie was selected to be part of the Glenfiddich Artists in Residence program, located in Dufftown, Scotland. The residency invites emerging and award-winning artists from all over the world to draw on a historical Scottish setting, located deep in the Highlands, in creating original works of art. It was an excellent opportunity for her to produce and exhibit work in an international context.

For the first time, Annie was creating outside of the 9-to-5 regularity of Kinngait Studios. She found the experience difficult and struggled with feelings of isolation while completing the residency. Nonetheless, she produced pivotal drawings, including Myself in Scotland, 2005–6, and Bagpipes, 2006. In Scotland she also created one of her first larger-format works, Balvenie Castle, 2006, which depicts a decaying site near the location of the residency. The drawing is richly coloured, with fine detail that brings it to life on the page. Although the castle was foreign to Annie’s visual vocabulary, she solved the problem of representation by combining colours and visual elements to create a hybrid structure that reflects both the Scottish landscape and her unique way of rendering the world.

That same year Annie was nominated for the Sobey Art Award, one of Canada’s few substantial art prizes not overseen or administered by government. Annie was the first Inuit artist to be nominated for this award, which came with a $50,000 cash prize. As a result of the isolation of Nunavut and the North from the mainstream art world, at the time of Annie’s nomination they were problematically not yet recognized by the Sobey Art Foundation as “designated regions of Canada” where contemporary art was being produced. As Wayne Baerwaldt, former director and curator of the Illingworth Kerr Gallery at the Alberta College of Art and Design (now Alberta University of the Arts) in Calgary, recalls: “I think there was… this long-standing perception that, because of its history, that ‘Inuit art’ is a commercial form of cultural production and therefore ‘artificial,’ while contemporary art from the south comes purely from the spirit of the artist and is therefore ‘authentic.’” This perception is a legacy of colonialism and it effectively suppressed professional recognition for the myriad contributions of Northern artists to the artistic landscape of Canada. However, when curator Patricia Deadman put forth Annie’s name for consideration, the committee acted swiftly to create a new geographical category called “Prairies & the North,” which includes the entire region of Inuit Nunangat (the Inuit homeland).

In November 2006 the award exhibition was held at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Annie’s competitors were Vancouver multimedia artist Steven Shearer (b.1968); Ontario-born digital artist Janice Kerbel (b.1969); the Quebec City collective BGL; and Halifax painter Mathew Reichertz (b.1969). Given that the North was not even recognized as an artistic hub in the eyes of the Sobey Art Foundation until that year, many—including the artist herself—were happily surprised when she was pronounced the winner. Annie’s straightforward pencil crayon drawings were not yet an established part of the conversation surrounding contemporary art, but jury members wrote in their assessment that her work “comes from a point when Modernism is being re-examined and reflects the hybrid nature of contemporary life. There’s really a lot to celebrate in the work of this artist.” Annie herself was quoted in the Nunatsiaq News on the historic recognition of her art: “I was excited…. They like my work, so I was happy.” She was thirty-seven years old.

Soon after Annie won the Sobey Art Award, she began to attract international attention. Ruth Noack, one of the curators of documenta 12, an important exhibition scheduled to be held in Kassel, Germany, in 2007, visited Toronto, and we met to discuss Annie’s work. The theme of documenta 12 was to bring “unexpected concurrences” to light by exploring the relationships “between works of art from different decades and cultures in which similar formal patterns have emerged.” documenta 12’s curators were looking for artists whose works showed the “‘migration’ of aesthetic forms across temporal and cultural boundaries culminating in the art of our postmodern world.” There was a fit, and Noack invited Annie to exhibit her drawings in Kassel.

Going abroad once again, Annie brought along a companion from Kinngait, Palaya Qiatsuq, who helped interpret for her and provided moral support during this professional landmark, and they travelled with Patricia Feheley and me. Still, the institutional art world Annie found in Kassel was of limited interest to her; she showed little inclination to attend meetings with other artists or curators. Always kind and respectful, Annie nonetheless questioned why her art shown at documenta 12 was not for sale (the reason was that it was an international exhibition and not a commercial art fair). In Kinngait selling her works regularly through Dorset Fine Arts and the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative had taken care of her immediate income needs.

Following documenta 12 the interest in Annie’s art remained steady, both in Canada and abroad. Between 2007 and 2010, a touring exhibition of her work travelled across North America. The Illingworth Kerr Gallery and the Confederation Centre of the Arts in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, were the institutions that organized the exhibition, which I curated. It was hosted at six galleries across Canada, before making its final stop at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City, where a young Tanya Tagaq performed at the opening. The New York Times praised Annie for capturing “life as one contemporary eye sees and depicts it” and creating “a single extended vision that crosses documentary with diary, by an artist who is both a scrupulous recorder of a specific 21st-century reality and an imaginative but unromanticizing editor of that reality.”

The amount of critical attention focused on Annie in such a short time would have weighed on any young artist. Her work—at first very inexpensive at around $500 per drawing—doubled in price, and then tripled. She was launched on a path of artistic success few have the chance to experience. Within a few short years her drawings were being collected by museums, including the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, and the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, and by notable collectors. She not only was a critical and commercial success but also created much-needed space for conversations about and awareness of the North in global contemporary art.

Life in Montreal

In 2007 Annie moved to Montreal. She was now an artist who had won global acclaim; her work was commanding higher prices than ever before, and she was celebrated across Canada and beyond. She had kicked down the door for her peers, friends, and colleagues to be recognized on the global contemporary art stage. She also had her $50,000 prize, which was a sum of money larger than what she was used to receiving for her work in the context of Kinngait Studios. Unfortunately, Montreal became the setting for a difficult time in her life: she struggled with substance abuse and abusive domestic relationships. Just a few months after her arrival, her money had been spent, shared, or taken.

Paul Machnik, who runs Studio PM in Montreal, and his partner Bess Muhlstock, an emergency nurse, checked in on Annie daily and provided her with a space in which she could work. For months Machnik and Muhlstock provided care and some financial support for Annie and tried to motivate her to produce drawings, sending her finished work to Dorset Fine Arts in Toronto, which was still distributing her work through Feheley Fine Arts. During this time she tried oil stick drawing as a departure from the pencil crayon drawings she had been producing in Kinngait; an example of this style is Composition (Drawing of My Grandmother’s Glasses), which was exhibited at Art Toronto, an international art fair, in 2007 and purchased by the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

Other drawings produced in Montreal continued to chronicle her daily life but were less well received. The subject matter in Drinking Beer in Montreal, 2006, for example, represents content similar to that of her earlier autobiographical drawings from Kinngait. It also demonstrates her signature style and a technical skill that includes a play of shadows on the floor, a detail not seen in her earlier works. The drawing is a prime example of the narrative realism that Annie had practised for years in the North—yet the Montreal works did not whet the appetites of contemporary collectors and the institutional art system. Their settings lacked the problematically sought-after “otherness” of Annie’s Arctic home. The unenthusiastic reception of these artworks points to the ways that notions of exoticism, ethnic novelty, and an exploitation of difference continue to permeate today’s contemporary art world.

In the fall of 2007 Machnik and Patricia Feheley helped purchase a ticket for Annie to return home to the security of her family and community in Kinngait. However, her stay there was short. Within a month of her arrival, the hamlet asked Annie to accompany an Elder on a medical trip to Ottawa as translator. Machnik later observed, “We put so much energy into trying to get her up there and settled in her home, and without thinking, Social Services gave her a ticket right back again. It was a shortcoming, on their part, not to review her situation first, because she was already in difficulties.” Annie was keen to return to the South, where she believed she would be successful on her own.

Ottawa and Her Final Years

Once Annie landed in Ottawa in January 2008, the difficulties that she experienced in Montreal began to resurface. She no longer identified as one of the artists with the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative and her work was no longer purchased on a weekly basis, the arrangement she was accustomed to at Kinngait Studios that had provided her with a regular professional routine and financial stability. Outside the umbrella of the Co-op and her community, Annie was left isolated in her negotiation of the art world and the city.

As with many artists trying to establish themselves professionally, representing herself as an independent contemporary artist was a skill Annie had not acquired. Much of an artist’s reputation in the contemporary art world relies on placing the right work in a suitable gallery or exhibition, putting out timely publications, and maintaining a social profile—in other words, it relies on a set of European-colonial attainments and attributes. To decolonize the contemporary art world is also to rethink the expectations and limitations we place on the Inuit art world; Annie became caught in the crossfire of these two shifting standards. In comparison to Kinngait, Ottawa and Montreal as the context for Annie’s art were perceived as not being remote enough, not “mysterious” enough to inspire a conversation about the shock value of crossing cultural boundaries. Troublingly, the drawings were considered sad as opposed to avant-garde and edgy—the calling cards of the contemporary art world. These works were not as popular with buyers or curators, yet they are important. Works like Annie and Andre, 2009, are a powerful reminder and reflection of the lives of many Southerners and urban Inuit living in the South.

While there is a large population of Inuit in Ottawa, where Annie could be close to some people from the North that she knew, substance abuse had begun to take a toll on her life. Combined with her shrinking funds, this struggle meant that at times she found it hard to make ends meet. Patricia Feheley, deeply concerned, checked in on Annie when she could. Although Annie knew many people in Ottawa, including Sandra Dyck at the Carleton University Art Gallery and Christine Lalonde at the National Gallery of Canada, and she had the support of Galerie SAW Gallery and particularly Jason St-Laurent, who offered her a place to work and exhibit, she was also exposed to domestic partners and commercial associates who took advantage of her situation.

In Ottawa Annie’s participation in the art world came to a near halt, but there were important exceptions. She was honoured to meet Canadian Governor General Michaëlle Jean alongside Kenojuak Ashevak (1927–2013) in 2009 and commemorated the experience with the work Untitled (Kenojuak and Annie with Governor General Michaëlle Jean), 2010. She notably participated in the opening of Dorset Seen, 2013, curated by Dyck with Leslie Boyd and held at the Carleton University Art Gallery. Remembering that occasion, William (Bill) Ritchie noted that she “looked like a million bucks.” It was an important exhibition that took the pulse of recent developments in the Dorset community’s art scene, which owed much to Annie’s own exploration of themes of consumerism, technology and transport, and mental illness. Annie also regularly visited Galerie SAW Gallery to chat with St-Laurent, who featured some of her early work in the 2015 exhibition BIG BANG. St-Laurent later noted how heavily Annie’s celebrity weighed upon her. Each time a new invasive feature that drew attention to Annie’s private living situation appeared in the local media, she would disappear for months at a time.

Annie’s battles with substance abuse put a serious strain on her life in Ottawa. She began a cycle of living on the street or in shelters. To support herself, she sold what drawings she had time to make to art buyers looking for a “deal” or to tourists. The prices they paid for these drawings were next to nothing in comparison to what she had earned in the past and far lower than what she had received as a Co-op artist, ultimately devaluing the commercial potential of her work. Friends of hers later spoke to Nunatsiaq News about this period in Annie’s life, saying that she once told them she was “‘afraid for her life’—that she was hiding, fleeing from an abusive relationship.”

On September 19, 2016, Annie drowned in the Rideau River in Ottawa. The police declared it a “suspicious death.” Her drowning and the subsequent investigation drew significant attention because of her status as an internationally renowned artist. The lead investigator in the case, Sergeant Chris Hrnchiar, posted online comments that were condemned and labelled as racist—he wrote that it was likely her death was due to alcoholism or drug abuse because of her ethnicity. In November 2016, Hrnchiar pled guilty to two counts of discreditable conduct under the Police Services Act.

Annie is survived by her three children. Her eldest son, Appa (b.1987), was adopted by Kuiga (Kiugak) Ashoona (1933–2014) in Kinngait. Her second son, Salamonie (b.1994), was raised in Iqaluit by relatives. Her daughter Napachie (b.2012) was taken into foster care and later adopted in Ottawa by Veldon Coburn. In 2017 Hrnchiar, Coburn, young Napachie, and her cousin Ellie canoed together up the Rideau Canal during the seventeenth annual Flotilla for Friendship.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements