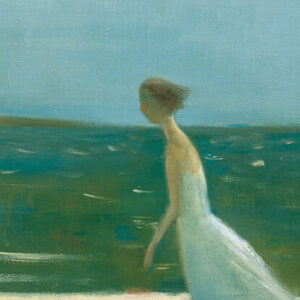

The Ursuline Nuns 1951

Jean Paul Lemieux, The Ursuline Nuns (Les Ursulines), 1951

Oil on canvas, 61 x 76 cm

Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Quebec City

The Ursuline Nuns signals a maturing of the visual language through which the painter would assert his artistic personality. By simplifying the composition and eliminating modelling, he was able to free himself from the anecdotal elements that had characterized his primitivist period (1940–1946).

For Lemieux, portraying his times in painted form required a long process of investigation, research, and refinement by trial and error. An assessment of his creative process can be made by comparing the final work with the preliminary sketch (pictured on the right), painted the same year. He divides the pictorial space into a restricted range of horizontal, vertical, and angled motifs softened by a few curving lines: the nuns’ veils, the three arcades, and a blind doorway. This geometric design has the effect of suggesting permanence, an impression reinforced by the sober colours. In the sketch, the painter opted for a brighter palette dominated by ochre, orange, and green, with a few piercing notes of red. For the finished work he chose colder colours and modulations of black and white. The Ursuline Nuns is a striking example of formal and chromatic unity.

The blank walls of the buildings, the bricked-up openings, and the absence of a horizon add a sense of enclosure, increasing the effect of settled permanence. The nuns, who came from Tours and Dieppe in the seventeenth century to devote themselves to the education of Native and French settlers’ children, remained a cloistered order until 1967. Lemieux shows them in their garden, the only place they were allowed to go outside the walls of the convent.

The Ursuline Nuns is a powerful evocation of the monastic life, and of movement suspended in an undefined moment of time, in which only the tree, the basket of fruit, and the cast shadows bring us back to the reality of a sunny summer day.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements