The work of Kathleen Munn broadens our understanding of the modern art movement in Canada. As her contemporary Bertram Brooker explained, she distilled “the most modern and the most ancient art” into a stunning expression entirely her own. Munn is notable for experimenting with abstract art earlier than most other artists in Canada; her studies and wide-ranging explorations contribute to her originality.

Significance

Kathleen Munn was among the few early twentieth-century Canadian artists to experiment with modern art techniques and styles, such as Post-Impressionism, Cubism, and Synchromism. During the 1910s and 1920s Munn developed her signature use of bold colours to paint traditional subject matter in works such as Untitled (Cows on a Hillside), c. 1916, and The Dance, c. 1923. Munn was also one of the first Canadian painters to create abstract compositions, including Untitled I and Untitled II, c. 1926–28, though she did not exhibit them.

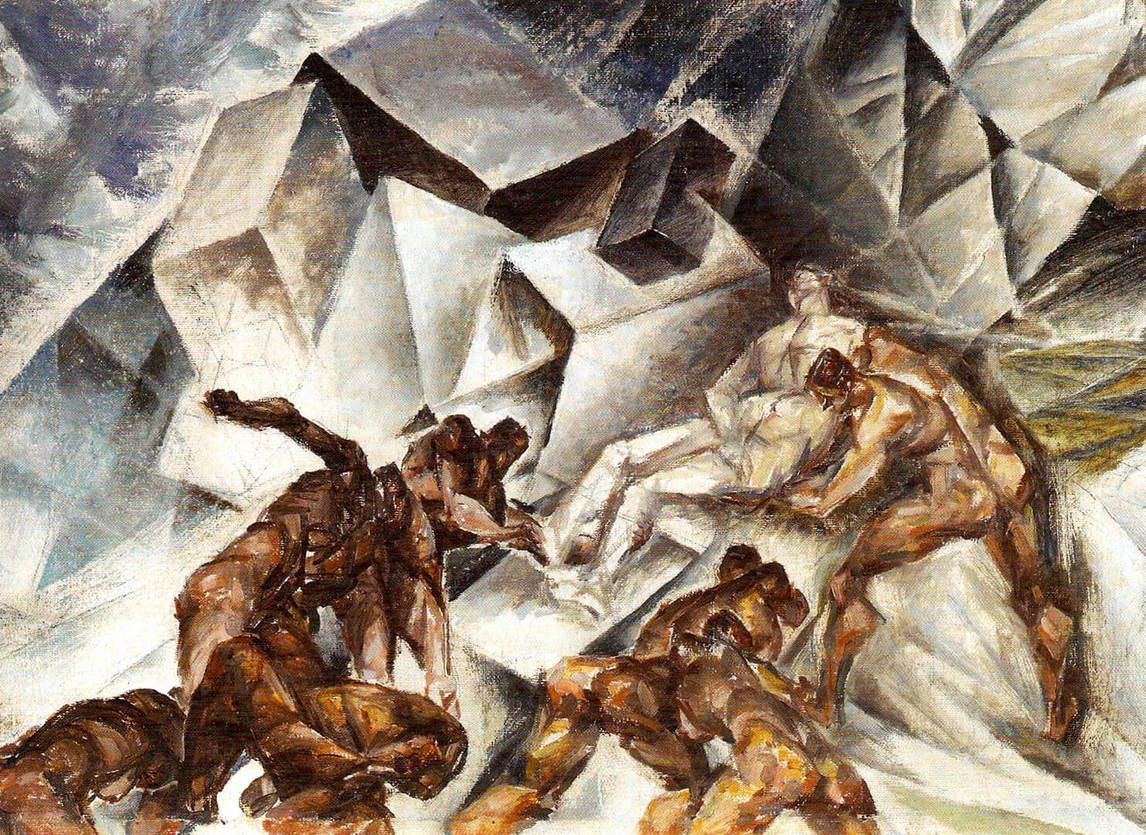

In the 1930s, after close study of the theory of dynamic symmetry, developed by Jay Hambidge (1867–1924), a significant shift took place in Munn’s art with her Passion series. In these works she radicalized the academic tradition of the human figure by reimagining its expressive and conceptual potential.

Munn’s work leads us to a deeper understanding of the development of modern art in Canada and of how artists responded to contemporary ideas that were in play in the international art world at a time when very little avant-garde art was being shown domestically. Munn shaped her own vision rather than follow the direction promoted by the national art movement represented by the Group of Seven.

Munn’s dynamic and colourful paintings—such as The Dance—were exhibited alongside the work of her Canadian contemporaries, where they were seen as baffling and out of place. Art critic Newton MacTavish’s description of her work in 1925 is typical: “Perhaps she is too far advanced for the average conception, for some of her best work is in danger of being misunderstood.”

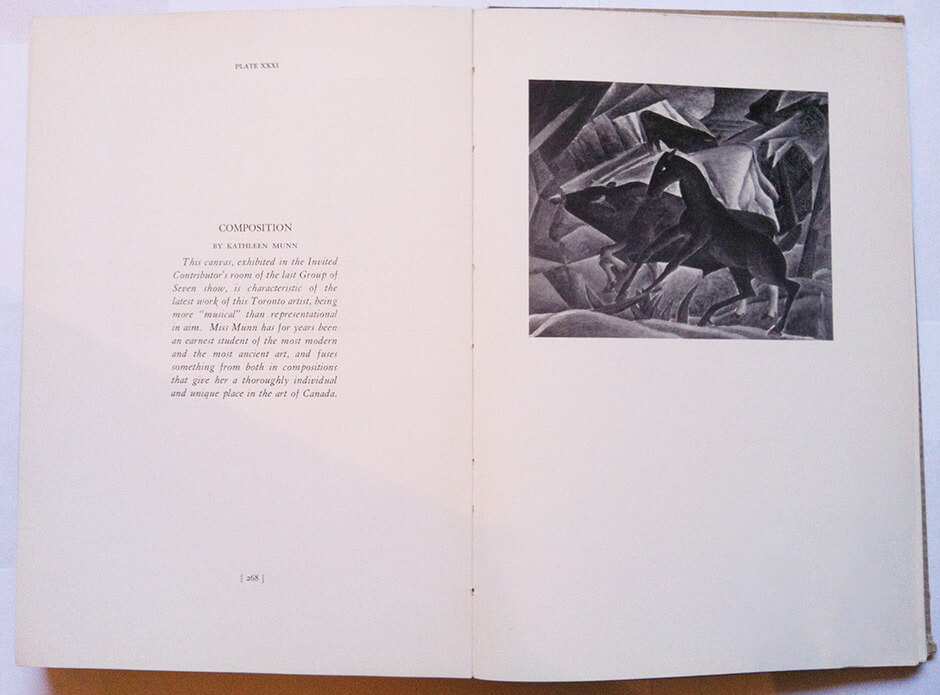

Bertram Brooker (1888–1955) was among the first to understand and articulate Munn’s unique modernism. In his Yearbook of the Arts in Canada, 1928–1929, he singled her out for being committed to both “the most modern and the most ancient art” and reproduced her painting Composition (Horses), c. 1927. Munn believed in the contemporary relevance of historical expression and understood historical art as the ancestry of modernity. She was determined to realize a new expression with ancient roots that would stand out as her own.

Critical Issues

In Munn’s ten known large ink and graphite drawings inspired by the Passion and Resurrection of Christ—including Descent from the Cross, c. 1934–35, and Last Supper, 1938—she brought together her dual interest in modern art and canonical themes. In European art Christ’s story represents the transformation of matter into spirit, object into idea. Jay Hambidge’s writings on dynamic symmetry offered Munn a theoretical and practical framework through which she could explore the relationship between object (what we know) and idea (what we seek).

Ideas of beauty are central to Munn’s work. As she noted, “Perfect beauty is the expression of perfect order, balance, harmony, rhythm. Beauty is a supreme instance of order intuitively felt, instinctively appreciated.” When Munn wrote in her notebook, in the 1920s, “I am going to do something next year so massive in construction and so simple that it will stand out against everything,” she declared her commitment to a grand project of classic proportions; her interest was not in the immediate or specific, rather it was in the timeless and universal. Although she stated in 1924 that “no one artist can represent all the beauty of life,” she was determined to attempt just that.

From the late 1920s Munn worked exclusively, and intensely, on Passion scenes. She understood that her attempt to “represent all the beauty of life” required abandonment to achieve a breakthrough. Her Passion-themed painting Untitled (Deposition), c. 1926–28, is evidence of this, as it appears to be a trial and exploration rather than a finished work. The relationship between the Passion drawings and paintings remains a rich area for future investigation.

Since the late 1980s, research, exhibitions, and writings have begun to address Munn’s contribution to art in Canada. The work of Kathleen Munn compels us to examine how the history of art is written and how an individual artist engages with modernism.

Theory

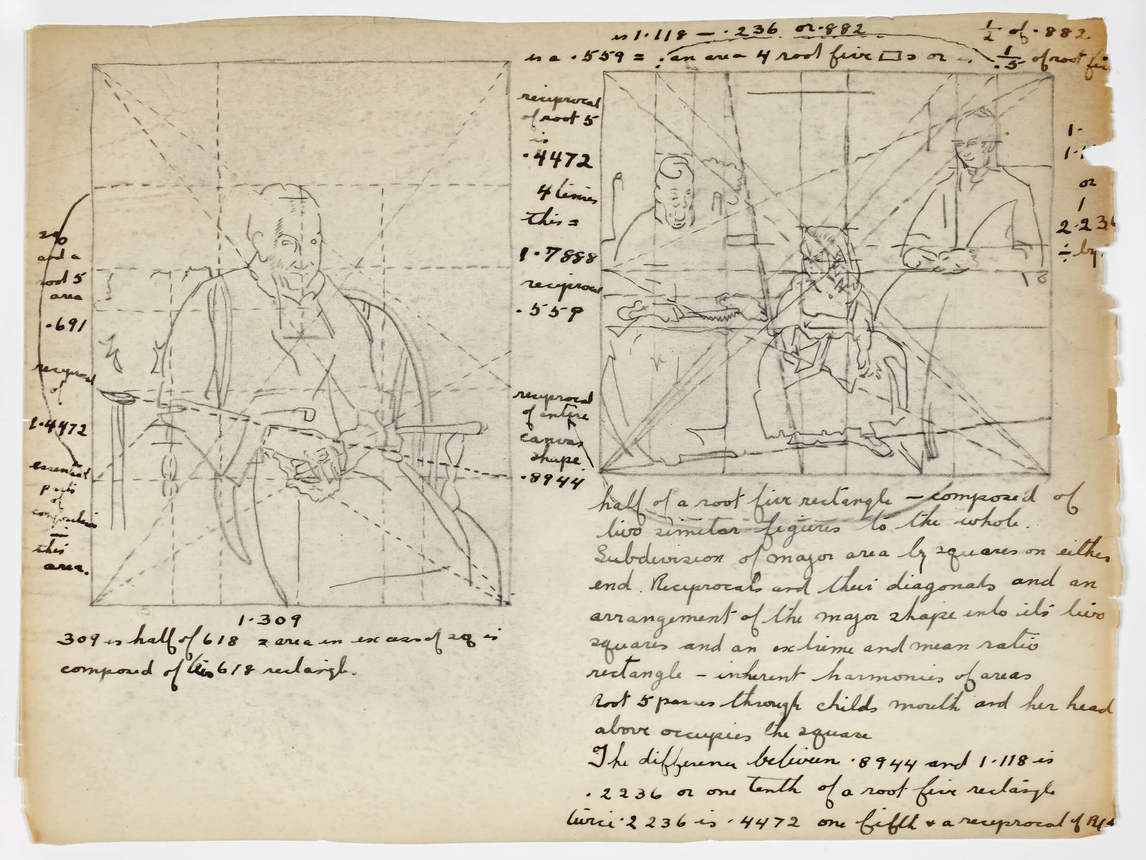

While Munn never explicitly wrote about Hambidge, it is clear from her decade-long experimentation with his theories that his essays confirmed for her the primacy of the human form and suggested a methodology for its representation. However, her interpretation and application of his theories are wholly original.

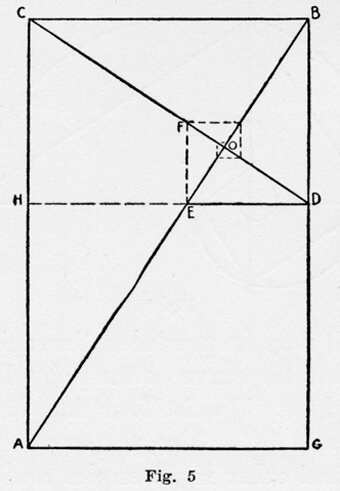

In the introduction to his “Lessons” from 1919, Jay Hambidge argues for the development of modern art rooted in classical principles. “The basic principles underlying the greatest art so far produced in the world may be found in the proportions of the human figure and in the growing plant,” he writes. “The dynamic is a symmetry suggestive of life and movement,” and the “symmetry of man” is one of the key sources for its study. Echoing these words, Munn stated how she sought to achieve in her work “something inevitable found in composing, like nature, like the universe—space rhythm harmony—creating a mathematical feeling.”

Hambidge offered explicit mathematical instructions and diagrams demonstrating the principles of dynamic symmetry as derived from nature and Greek art. His concept of the “rectangle of the whirling squares”—numerically expressed as 1.618 and commonly referred to as the “golden ratio”—was most important to Munn. It is at the core of dynamic symmetry and proportion. In 1923 Hambidge lauded the use of dynamic symmetry by American artists—George Bellows (1882–1925), specifically—and declared that “much of the weakness of modern art is due to too much sex, too much sentiment, and too little design.” Munn copied and underlined this passage in her notebook. She produced over one thousand drawings of the human figure based on the principles of the whirling square.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements