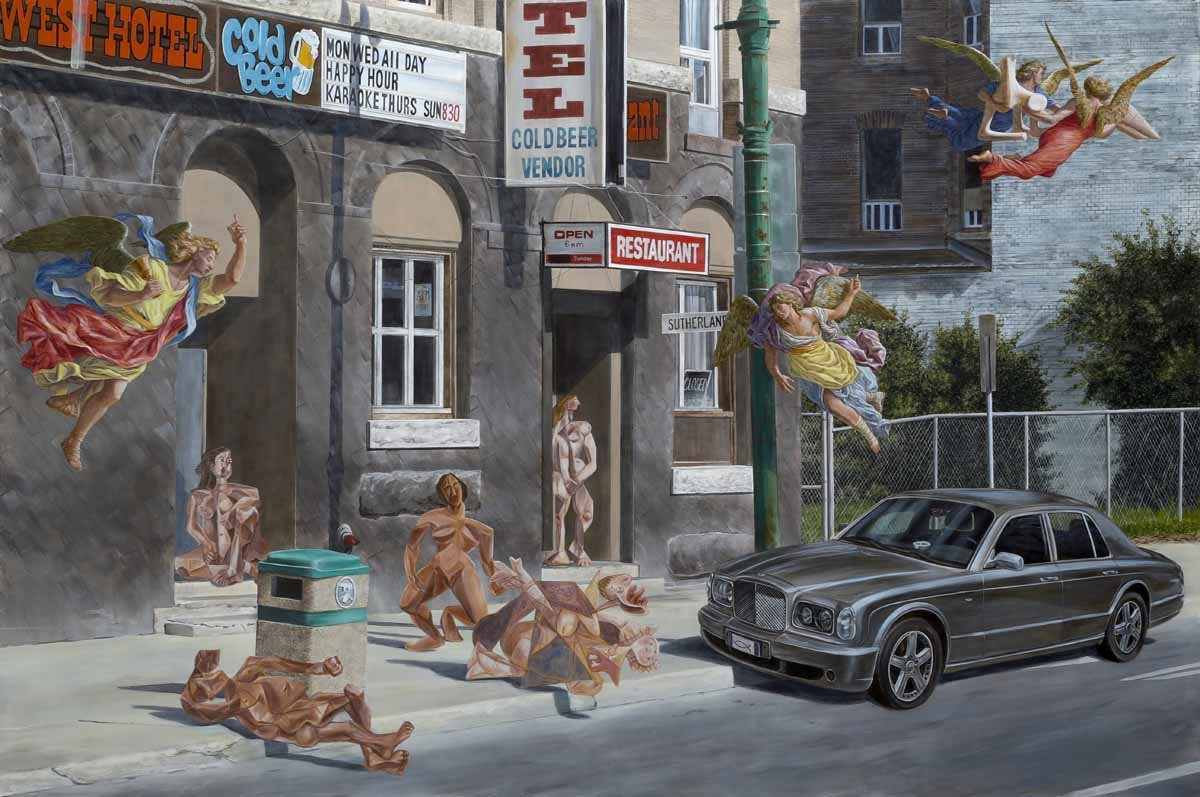

Le Petit déjeuner sur l’herbe 2014

Kent Monkman, Le Petit déjeuner sur l’herbe, 2014

Acrylic on canvas, 213.4 x 320 cm

Collection of the National Bank of Canada

Le Petit déjeuner sur l’herbe is a part of the Urban Res series that Kent Monkman produced between 2013 and 2016, which focuses on Winnipeg’s North End community, home to many Indigenous peoples. The setting is the compressed, confined space of the city. There is little landscape except for what is seen through a chain-link fence. The naked figures of women lying in the street are made of multiple flattened planes, sharp angular shapes, and chopped, distorted forms appropriated from Cubism and the radical reinventions of female nudes by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973). They are a parody of that artist’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, a famous group portrait of prostitutes in Barcelona. An expensive car is parked outside, implying that the owner is upstairs with one of the women. The abuse and violence implicit in the scene are underscored by a figure modelled on Picasso’s air-raid mural, Guernica, 1937. Monkman has described the series as depicting a hostile environment of “the predator and prey,” and in particular, the reality that “Indigenous women are preyed upon.”

The title of this painting references Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1863, by Édouard Manet (1832–1883), which was considered groundbreaking in its time as a key example of modernism. In that work, a nude woman gazes directly at the viewer as she sits with two clothed men on the grass in a park. Manet’s representation of the woman countered the demure, idealized nude of the academic tradition, and in collapsing pictorial space he favoured a flattened, modernist approach. Commenting on the composition, Monkman noted that Manet “transformed conventions of pictorial space and set Modernism on its path,” and suggested that “the painter’s flattening of pictorial space echoes the shrinking of space for Indigenous people, who were forced onto reserves that are tiny fractions of their original territory now comprising only 0.2% of Canada.”

Monkman’s appropriations represent the colonialist and modernist violence inflicted on the female form and spirit. Referring to Picasso’s “butchering of the female nude,” Monkman’s work refutes European ideas and the impact of modernism that Indigenous cultures have faced, as well as the dehumanization endured by Indigenous women in particular. Monkman sees the whole modernist period in European art in parallel with the effects on Indigenous communities wrought by other symptoms of modernity, including the railways and the Indian Act. Picasso also acts as a foil for Monkman’s own sensibility and sexuality.

The angels seem to be a mysterious ambiguous presence in Monkman’s paintings. They hearken to the cherubs often seen in Baroque paintings, Renaissance ceilings, and sacred European frescoes, yet the angels in this work resemble women. They may signify grace but also the destructive impact of Christianity on First Nations communities—are they preying on souls or saving them? This duality allows Monkman to allude freely to the Old Master paintings he interrogates.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements