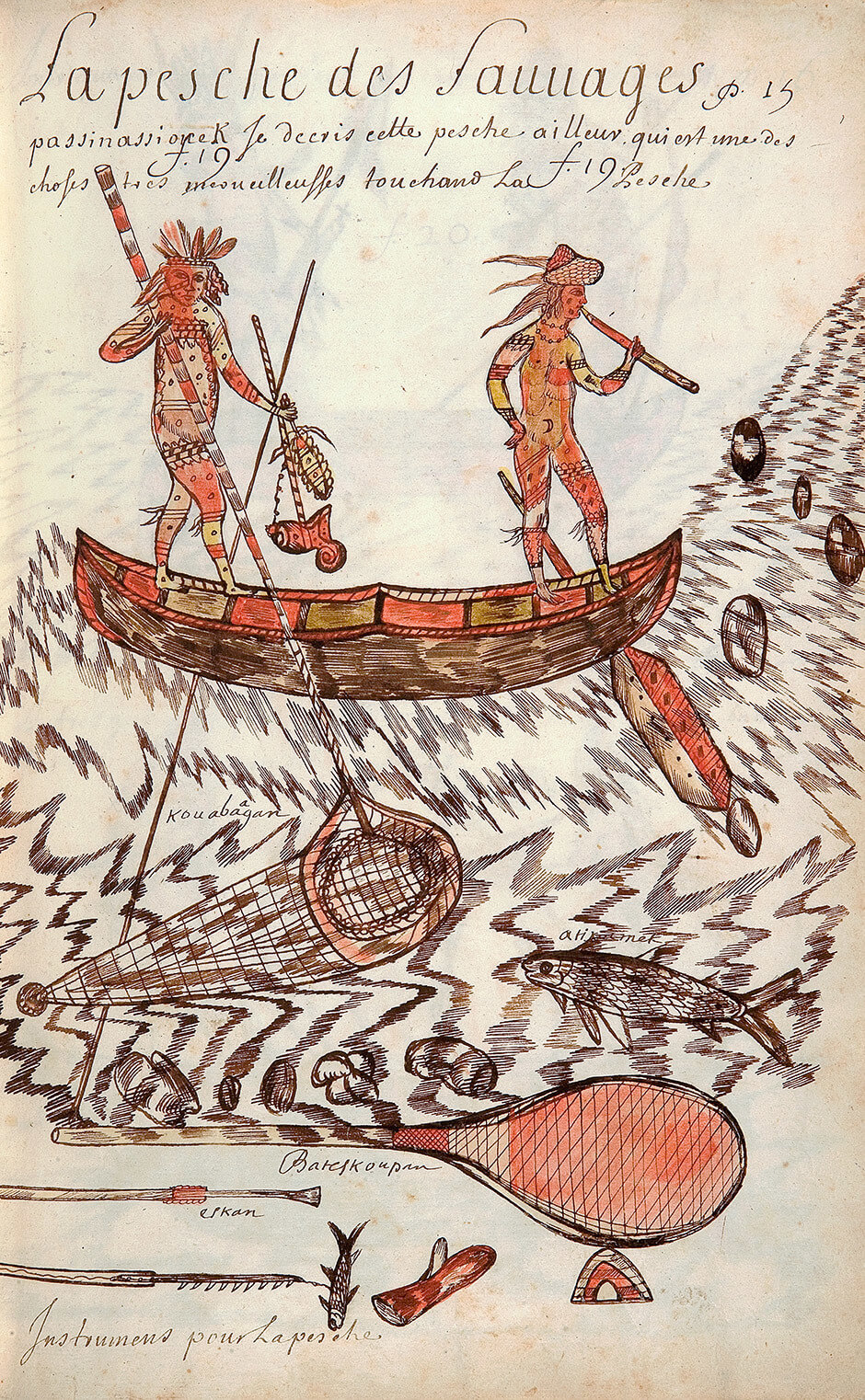

Fishing by the Passinassiouek n.d.

Louis Nicolas, Fishing by the Passinassiouek (La pesche des Sauvages), n.d.

Ink and watercolour on paper, 33.7 x 21.6 cm

Codex Canadensis, page 15

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

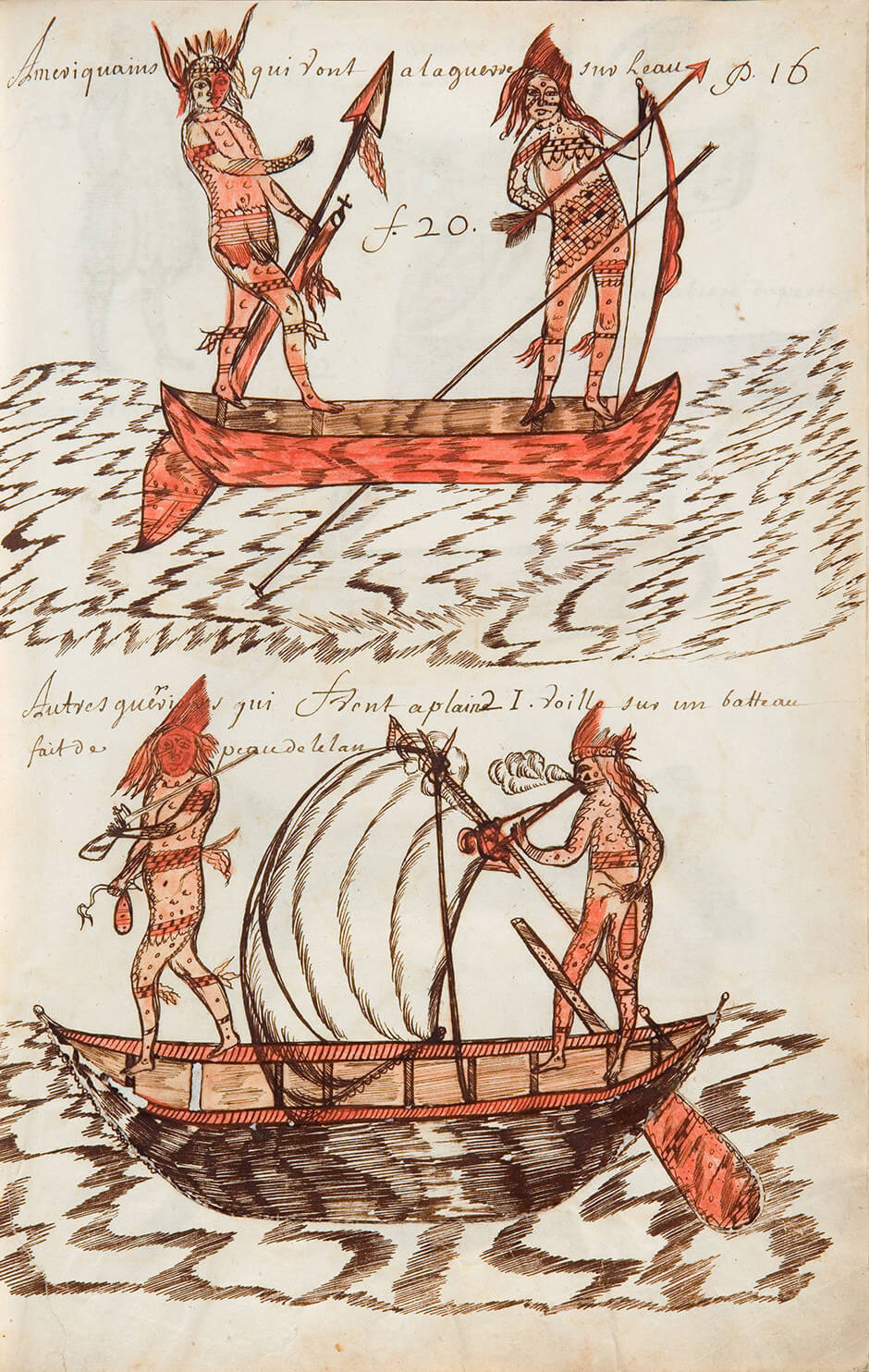

Fishing by the Passinassiouek depicts Sioux men from Eastern Dakota in a canoe, fishing on the rippling waters of southwestern Lake Superior. In the scant images he created depicting scenes of Indigenous life, Nicolas worked mainly from his own observations and relied, with a few exceptions, on his natural talent. The less-formal illustrations he created of people in their domestic surroundings, travelling, taking care of the dead, and so on, have a spontaneous if somewhat naïve quality that is not only appealing but provides valuable information about Indigenous cultures in the late seventeenth century.

In using the term “sauvages,” Nicolas was following his contemporary usage, which derived from a hierarchical conception of humanity. At the top of the pyramid were the king and the nobles; lower, the ordinary people; and lower still, the “sauvages,” a term used by the French to describe the Indigenous peoples of North America, because the colonizers erroneously considered the land’s original inhabitants not to have religions, intelligible languages, forms of government, or morals to speak of.

The men are holding nets and some of their catch, and Nicolas displays hooked spears and other fishing implements at the bottom left of the illustration. He seems determined to record as many details as he can in his illustrations. In addition, although he draws the image, as he always did, with a quill pen in brown-ink lines and strokes, this illustration is one of the few that he or someone else tinted—here with crimson and ochre watercolour.

In the caption, Nicolas indicates that he has described this practice elsewhere—and he may be referring to the following passage, which he wrote in The Natural History of the New World Histoire naturelle des Indes occidentales). There he describes seeing the Sioux and other Indigenous groups fishing during his visit to the Saint-Esprit Mission:

These Argonauts [fishermen] push their canoes violently into the middle of the rapids, until they arrive at places where they know that there are so many of these big white fish that the entire bottom of the water seems to be paved with them or rather they are piled up one on the other in such numbers that they have only to drop their second pole [the first pole is the one that anchors the canoes in the rapids], at the end of which there is a net in the shape of a cone or hood. Each time they raise it, as they do quickly, they bring up five or six large white fish. I gave a picture of the net in my figures.

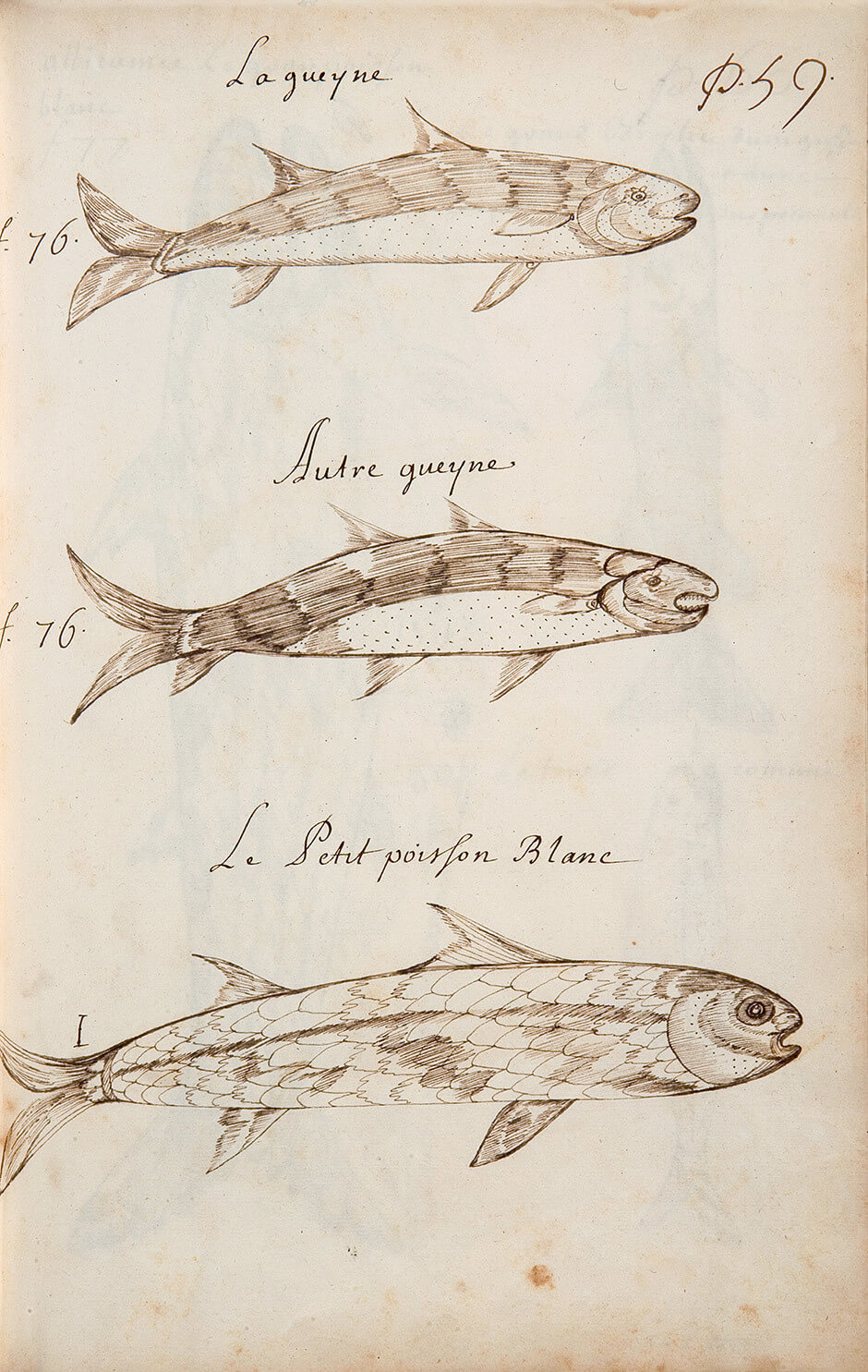

Elsewhere, dealing with “the small and large white fish,” he mentions the atigamek. Perhaps this reference correlates with the illustration of the fish, labelled atikamek, in the lower right of the drawing. The “large white fish” is identified as the Lake Whitefish and, Nicolas says, it is “hardly caught anywhere except in our great lakes, and never in salt water.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements