Flat Head Woman and Child c. 1849–52

Paul Kane, Flat Head Woman and Child, Caw-wacham, Cowlitz, c. 1849–52

Oil on canvas, 75.9 x 63.4 cm

Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto

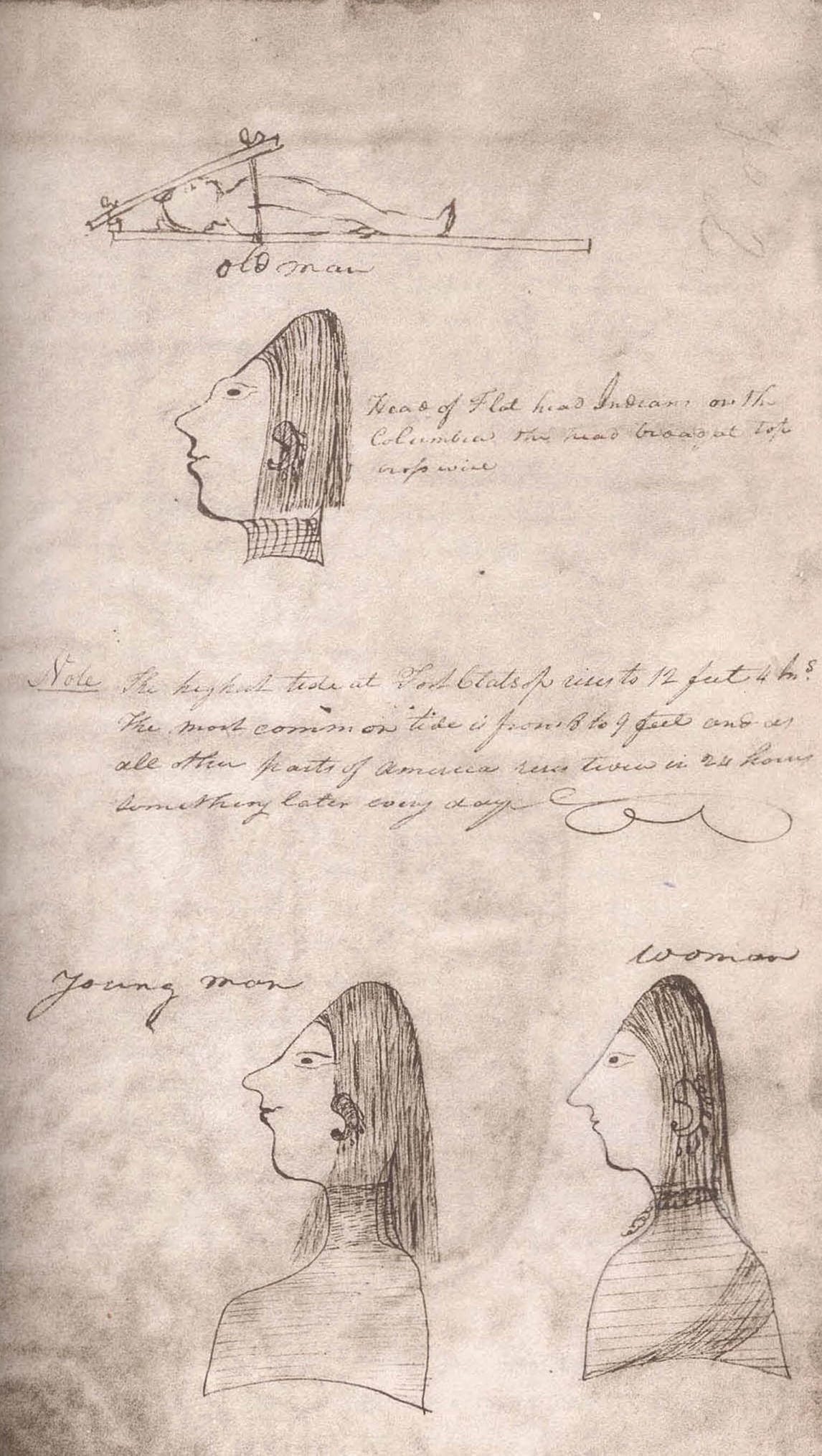

Flat Head Woman and Child, Caw-wacham was one of Kane’s best-known paintings in his day and has proven to be one of his most controversial works. It depicts a woman with an infant whose head is being reshaped; the woman’s own profile highlights the result of the traditional procedure. The image, inspired by Kane’s encounter with the Aboriginal peoples of the Columbia River Valley, is a composite based on separate watercolours of members of two or three different tribes: one Cowlitz (the infant) and the other Songhees or Southern Coast Salish (the woman). Kane makes no mention of the reshaping process in his field journal, but it is featured in his book Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America, including the explanation that the “flat” head is a “distinguishing mark of freedom.”

For all the attention and controversy the painting has engendered, it is ironic that Kane depicts the flattening board in the “up” position rather than actually pressuring the child’s skull, as was depicted in more documentary renderings of the procedure, such as a sketch from 1806 by William Clark (1770–1838) of a child in the process of having its head flattened.

Nineteenth-century responses to Flat Head Woman and Child addressed both aesthetic and ethnographic aspects. When Kane exhibited the painting (titled simply “Sketch of a Chinook”) in the portrait category at the 1852 Upper Canada Provincial Exhibition, it was appreciated as much for the colour of its background landscape as it was as a “trait of Indian customs.” Yet interest in its ethnographic references prevailed. The painting no doubt was on display at the Canadian Institute’s March 1855 meeting featuring a reading of Kane’s paper “The Chinook Indians,” which included a description of the reshaping procedure. The reading was complemented by a display of Chinook cultural objects, a skull, and “several admirable oil paintings, executed by Mr. Kane.” Flat Head Woman and Child was also the inspiration for an image created by Kane’s friend Daniel Wilson (1816–1892), who reviewed his book Wanderings of an Artist. Wilson made his own composite image for the frontispiece to his book Prehistoric Man using the same watercolour sketch of a Cowlitz infant and another by Kane of a Clallam woman weaving a basket.

Modern commentary is more critical in tone. The art historian Heather Dawkins has approached Flat Head Woman and Child, from a post-colonial perspective, taking Kane to task for his Victorian imperialist viewpoint evident in his disregard for tribal distinctions. And, given that Kane painted this “mother and child” theme at a time when Western culture was showing an increased respect toward children, she questions Kane’s motives in depicting this particular Aboriginal custom. Was he simply romanticizing Aboriginal life, or was he intentionally criticizing Aboriginal culture?

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements