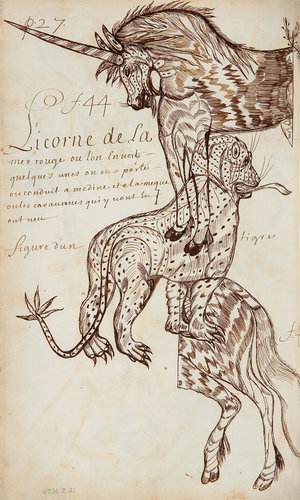

In his Codex Canadensis, the Jesuit documentarian of seventeenth-century Canada Louis Nicolas (1634–post 1700) begins the section on the wildlife he observed in New France with this extraordinary depiction of a tiger and the mythological unicorn. Nicolas was certain that unicorns existed and insisted he had seen one killed. But he also knew that neither the unicorn nor the tiger were native to the New World. So why would he include these animals in a book about New France?

Louis Nicolas, Unicorn of the Red Sea (Licorne de La mer rouge), n.d.

Ink on paper, 33.7 x 21.6 cm, Codex Canadensis, page 27, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Paradoxically, Nicolas used the example of the unicorn to emphasize the importance of direct observation over purely bookish information. The creature would disparage “les gens de cabinet” who didn’t believe in unicorns simply because they had never travelled outside their parish. As he wrote in the The Natural History of the New World (Histoire naturelle des Indes occidentales):

“I do not know what to say about the appalling error that has crept in even among many learned people who are otherwise very knowledgeable, but have seen nothing of the admirable things produced by nature because they have never lost sight of their parish church tower, and who hardly know how to get to the Place Maubert or the Place Royale without asking the way. I say that these people are stubborn to insist that there is no unicorn anywhere in the world.”

This Spotlight is excerpted from Louis Nicolas: Life & Work by François-Marc Gagnon.

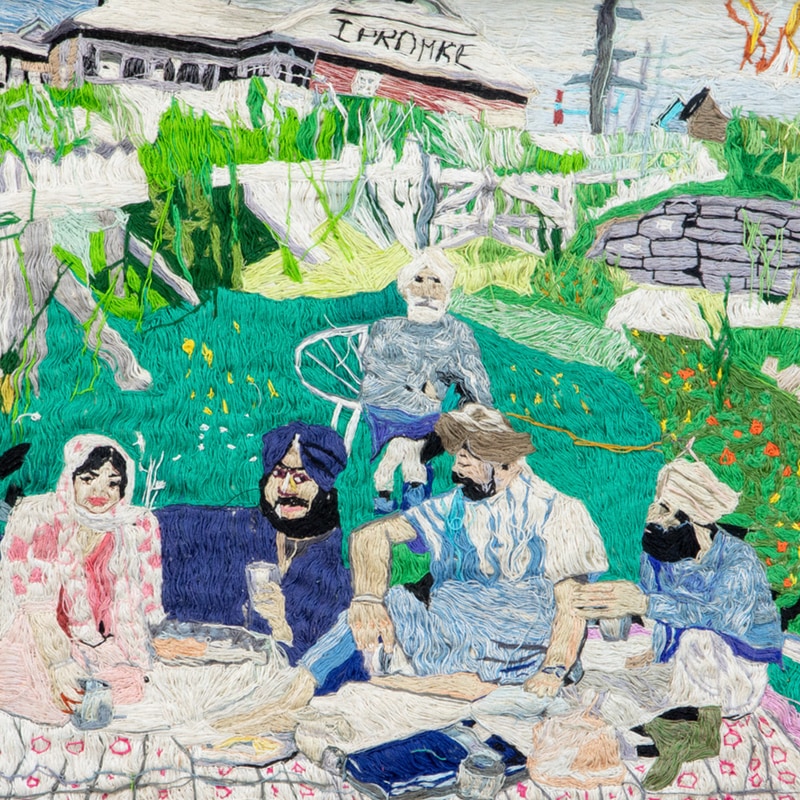

Stitching the Archives

Stitching the Archives

A Working-Class Hero

A Working-Class Hero

Imagining Entangled Futures

Imagining Entangled Futures

Bridging Far and Near

Bridging Far and Near

Soft Power

Soft Power

Imagining Emancipation

Imagining Emancipation

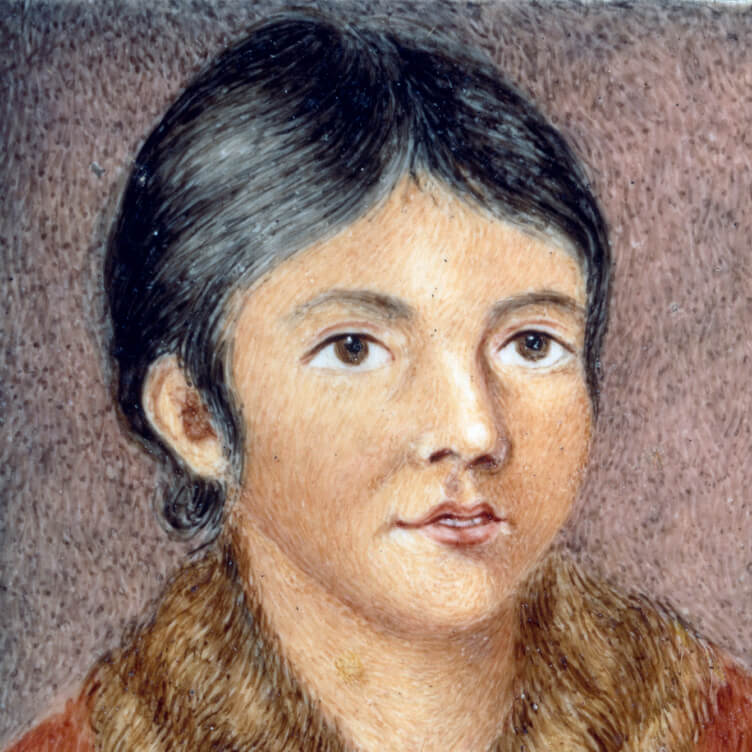

A Priceless Portrait

A Priceless Portrait

Meditation in Monochrome

Meditation in Monochrome

Making His Mark

Making His Mark

Honour and Sacrifice

Honour and Sacrifice

A Monstrous Vision

A Monstrous Vision

Remote Beauty

Remote Beauty

Pride and Resistance

Pride and Resistance

Dressed for Danger

Dressed for Danger

Masks from the Past

Masks from the Past

Lessons from the Land

Lessons from the Land

A Cultural Hero

A Cultural Hero

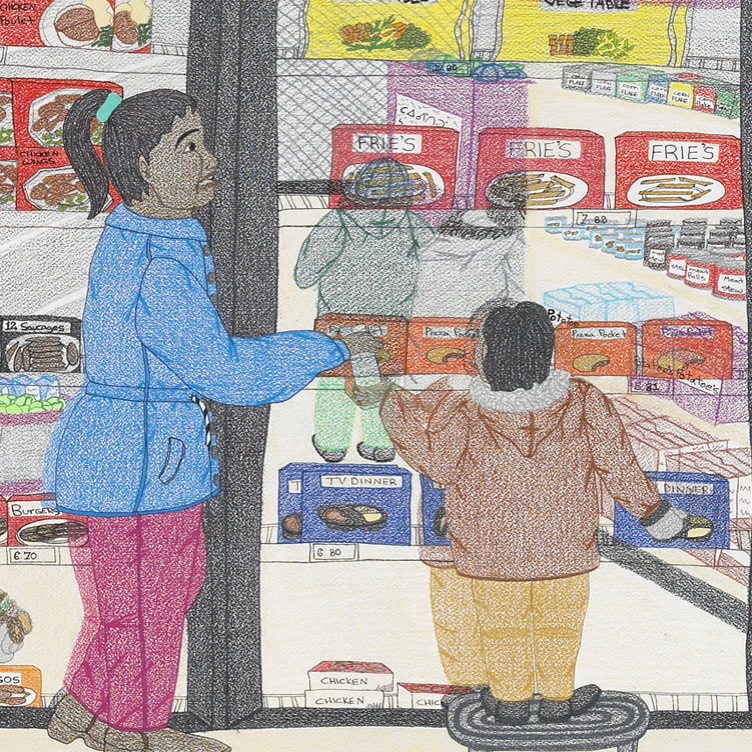

Food for Thought

Food for Thought

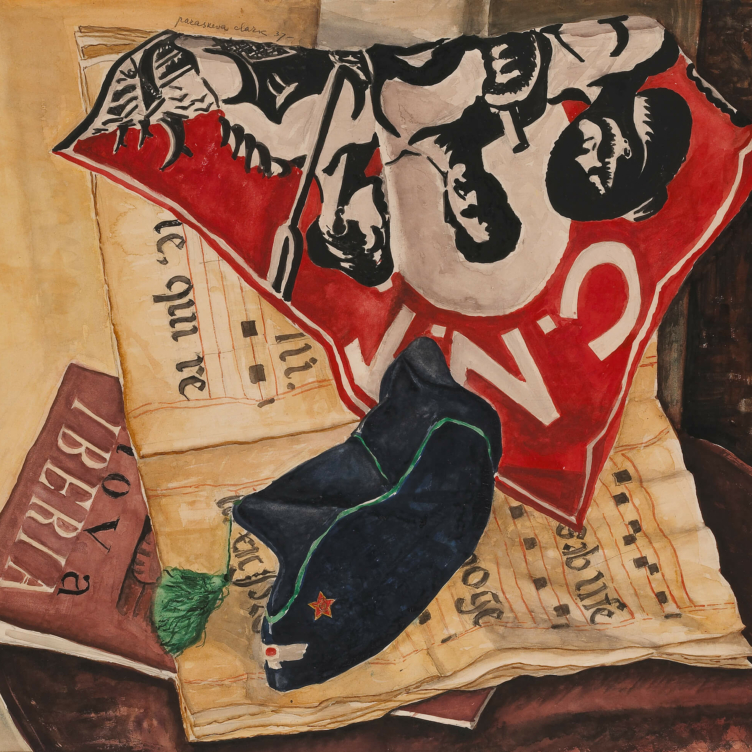

A Passion for Activism

A Passion for Activism

Starvation and Scandal

Starvation and Scandal