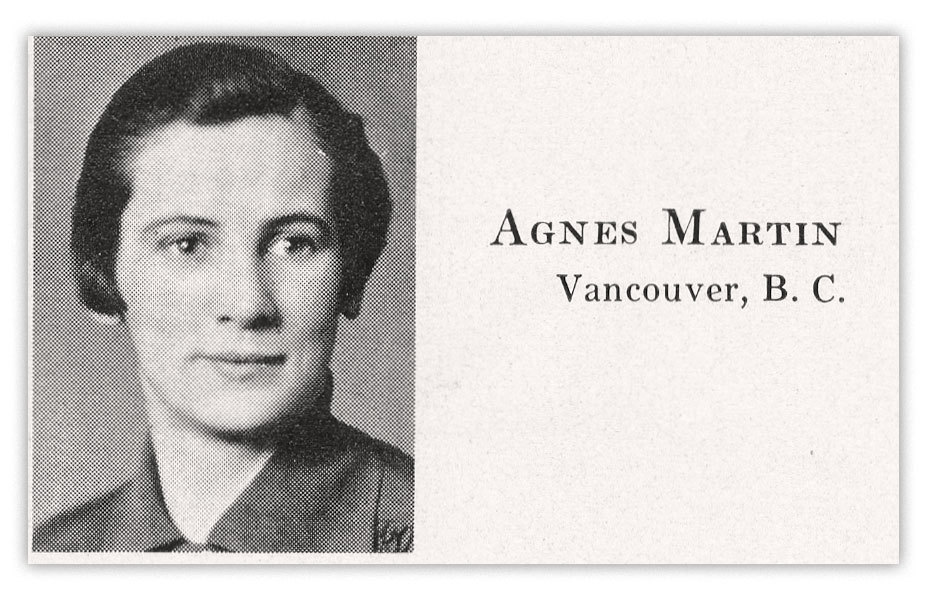

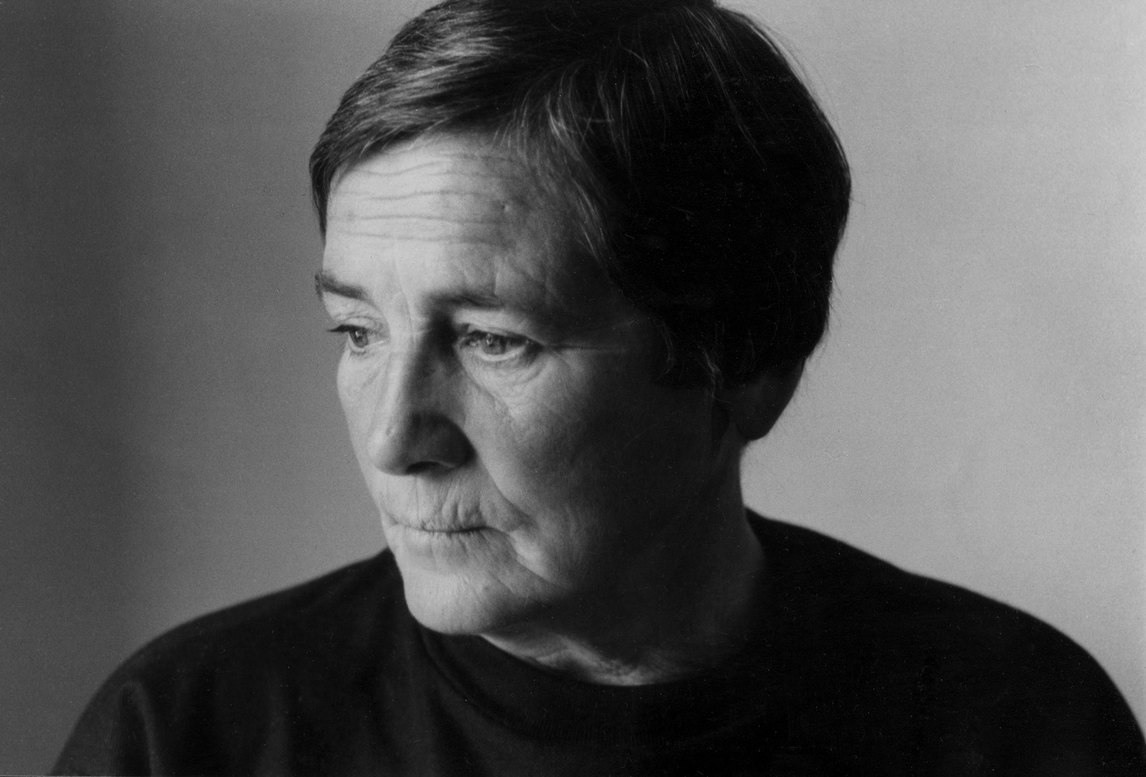

Agnes Martin (1912–2004) is best known as a painter of grids, where pencil lines and bands of colour fill square canvases and subtly evoke a variety of emotional states. She is a major figure in postwar American abstraction, and her work is collected and exhibited by museums of modern and contemporary art the world over. Born and raised in Canada, she moved to the United States as a young woman and considered herself part of the American art movement known as Abstract Expressionism. In recent years, her long-standing reputation within the art world as a “painter’s painter” has expanded into the wider culture. Some aspects of Martin’s biography—her family in Canada, her sexuality, and her mental health issues—have until recently remained obscure. What is certain is that over the course of a long life that was at times wandering and punctuated by moments of poverty, Martin developed one of the most rigorous, affecting, and coherent bodies of work of the twentieth century.

Early Life

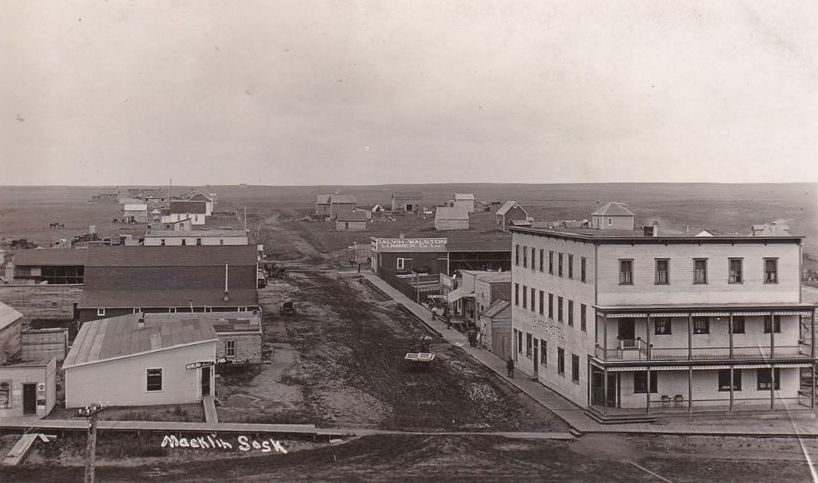

Agnes Bernice Martin was born in Macklin, Saskatchewan, on March 22, 1912. “My grandparents on both sides came from Scotland, and they went on to the prairie in covered wagons,” she said during an interview for the Archives of American Art in 1989. “My parents were also pioneers; they proved up a homestead in northern Saskatchewan, but my father also managed a wheat elevator and a chop mill.” In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, rural Saskatchewan was in the midst of a rise in European settlement. Like many settlers, Martin’s family was of Scottish Presbyterian descent. Both sides of her family immigrated to Canada around 1875, living first in Mount Forest, Ontario, before making their way to the Prairies.

Martin’s father, Malcolm Martin, established himself in Macklin in 1908 on land obtained from the government after having fought in the Boer War in South Africa. In April 1902, at age twenty-eight, he had enlisted in the 5th Regiment of the Canadian Mounted Rifles in Portage la Prairie, Manitoba; unmarried, he cited his profession as “grain buyer.” It is unclear how much action Malcolm saw in South Africa as hostilities ended a month after he enlisted. He died in June 1914, when Martin was only two. Her mother, Margaret, was the daughter of Robert Kinnon of Lumsden, Saskatchewan. Martin’s maternal grandmother died when Martin was roughly one year old, but her grandfather lived until 1936. Martin told the New Yorker’s Benita Eisler, “He didn’t talk to me, but somehow he influenced me tremendously.” Later, in a 1996 interview, she elaborated: “[He] believed that God looked after children. . . and that it was none of his business. Anyway, it made for a good life, I can tell you. Freedom.”

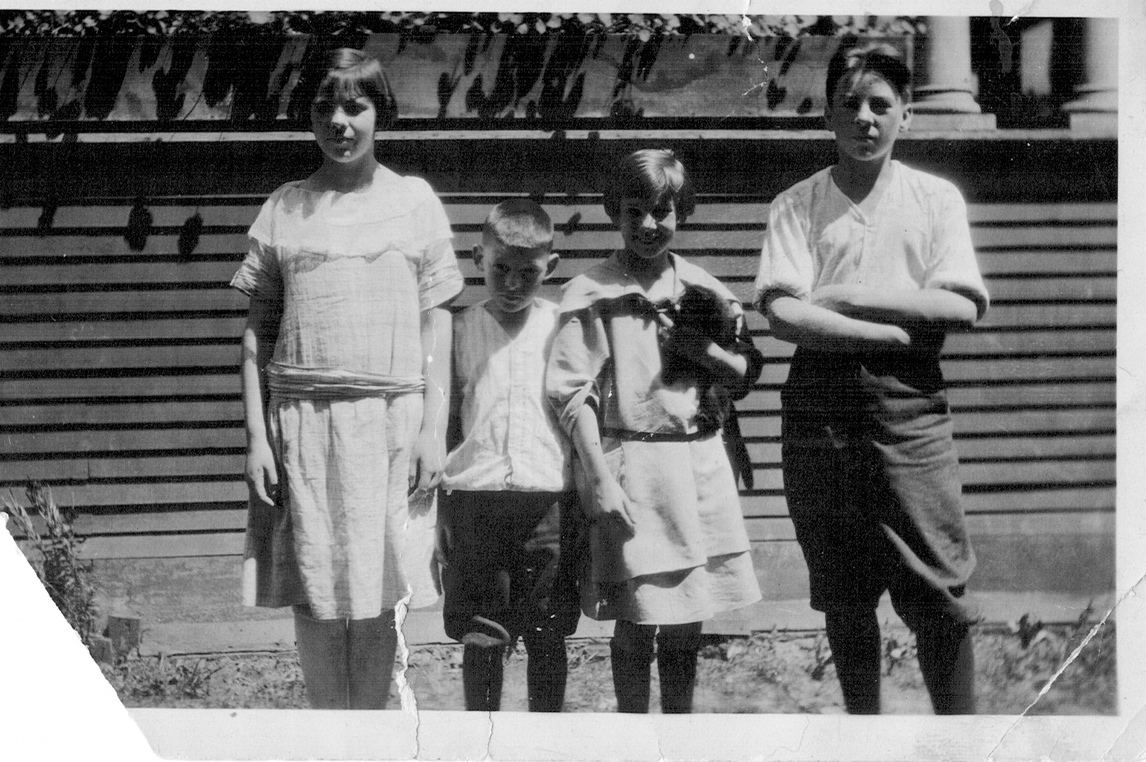

Martin was the third of four children; her siblings were Ronald, Maribel, and Malcolm Jr. The family moved several times in the years between Martin’s father’s death in 1914 and 1918—the years of the First World War. They left the farm in Macklin and spent time in Lumsden and Swift Current, Saskatchewan, and then Calgary, Alberta. By the end of the war, the family had found their way to Vancouver, British Columbia, where Margaret supported them by renovating and selling houses. They lived on Nelson Street in Vancouver’s West End. Martin felt neglected by her mother, saying, “She hated me, God how she hated me. She couldn’t bear to look at me or speak to me.” Martin attended Dawson Public School and later King George Secondary School. Her grandfather eventually moved to Victoria, just over one hundred kilometres from Vancouver across the Strait of Georgia on Vancouver Island, and she would visit him there.

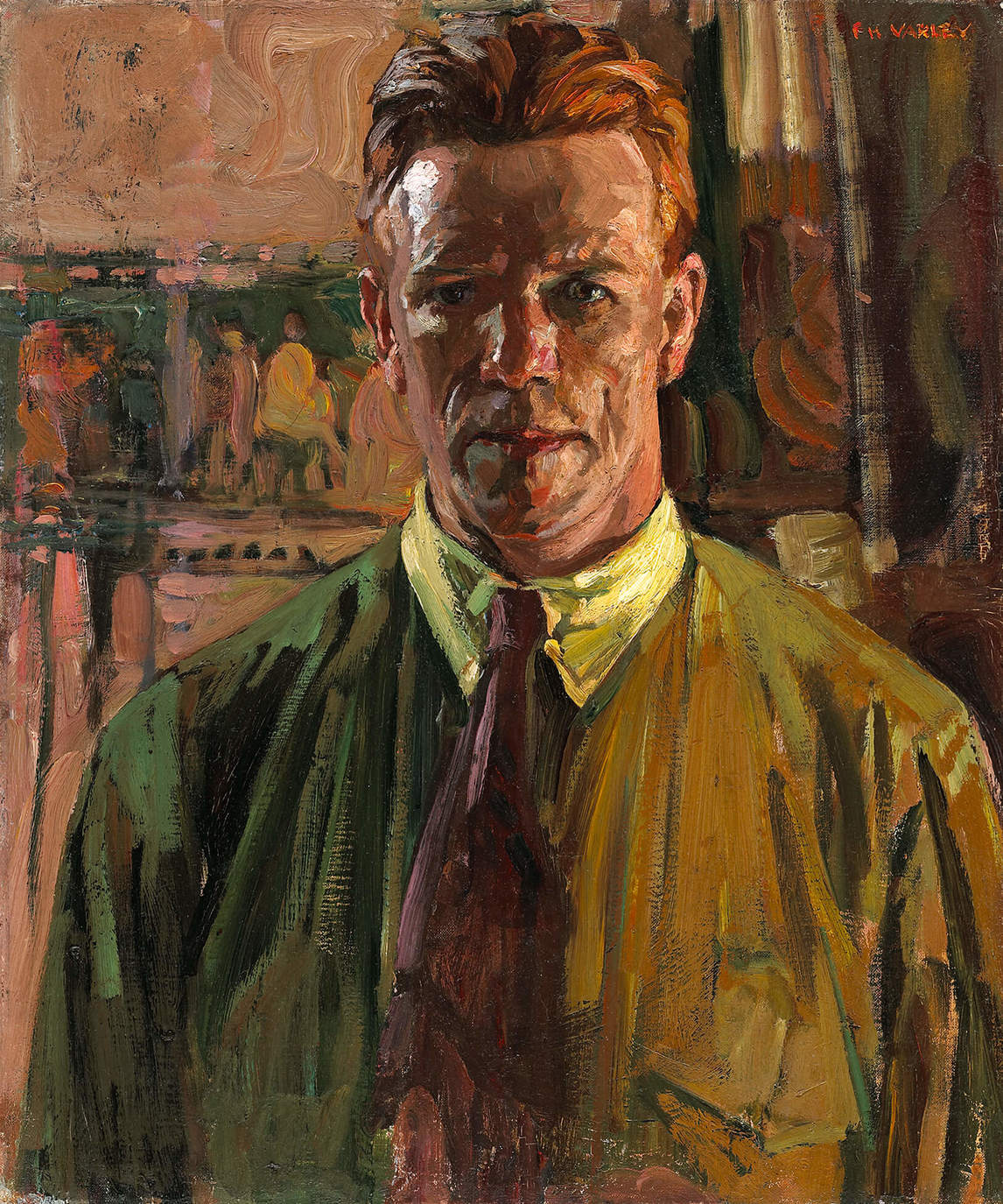

Vancouver was in a period of cultural growth during Martin’s teenage and young adult life. From 1921 to 1931, the British Columbia Art League operated an art gallery, which held regular exhibitions, including one by the Group of Seven in 1928. It was replaced in 1931 by the Vancouver Art Gallery. The School of Decorative and Applied Arts opened in 1925, and influential teachers Jock Macdonald (1897–1960) and F.H. Varley (1881–1969) began teaching there in 1926. Martin’s grandfather lived a short walk across Beacon Hill Park from the celebrated Canadian painter Emily Carr in Victoria. It is unclear how much Martin was exposed to the burgeoning west coast art scene. Her only public reminiscence recalls copying postcard reproductions of famous paintings while a student.

Emily Carr with her pets in the garden of her home at 646 Simcoe Street in Victoria, 1918, photographer unknown, Royal BC Museum and Archives, Victoria, British Columbia.

In Vancouver Martin cultivated a love of the outdoors—through hiking, camping, and, above all, swimming—that would stay with her the rest of her life. She likely began to swim while a student at King George Secondary School and trained with the renowned Canadian swimming coach Percy Norman (1904–1957). She told Eisler that she won the Canadian Olympic tryouts in 1928 but could not afford to attend the games in Amsterdam. She would try again in 1932; however notices from the Vancouver Sun and the Saskatoon StarPhoenix from July of that year report that Martin placed fourth in the qualifiers for the women’s 440-yard freestyle, falling short of qualifying for the Los Angeles Olympics.

By the time Martin had competed in the 1932 Olympic qualifying race, she was living for part of the year in Bellingham, Washington, with her sister, Maribel. “My sister married an American and she became ill and I came down to take care of her. Then I noticed the difference in American people and the Canadian people and I decided I wanted to come to America to live, not just to go to college but actually to become an American.” Martin was attracted to the American understanding of freedom and liberty, which she found different from her own Canadian experience of the concepts. Although she had graduated from King George Secondary School in Vancouver in 1929, she attended Whatcom High School in Bellingham in 1932 in order to matriculate to the Washington State Normal School, which she attended from 1933 to 1937. Martin’s excellence in athletics shone in Bellingham. She variously played baseball, volleyball, basketball, and tennis, and organized sporting and social functions.

Martin obtained a student visa and became a legal permanent resident of the United States on August 27, 1936, crossing at the Peace Arch in Surrey, British Columbia. “I couldn’t come to the United States unless I had a profession,” she would later say, “and I thought the easiest profession I could acquire would be to be a teacher.” While at the Normal School, Martin met Mildred Kane, who would become one of the most influential figures in Martin’s young adult life. Martin’s relationship with Mildred Kane has been described as romantic at times and platonic at others; it lasted until at least the mid-1950s. Kane was an emotional and sometimes financial support to Martin as she developed her career as an artist. Martin graduated in June 1937 but even with a teaching certificate it was difficult to find steady work during the Depression. She taught in three different rural Washington schools over the next four years and worked for the Canadian government as a liaison to the logging industry.

An Aspiring Artist

Motivated by her inability to find a permanent teaching job, Martin enrolled in a one-year program at Teachers College at Columbia University in New York City in the fall of 1941 to upgrade her teaching certificate to a bachelor’s degree. She moved with Kane, who began a doctorate in early childhood education. Her time in New York coincided with the United States entering the Second World War. Martin’s brother Malcolm Jr. served in the Royal Canadian Air Force, stationed in England and later in Victoria, B.C. She would boast that Malcolm was “the first Canadian to enlist.”

Martin not only took teaching courses but also studio classes in marionette production, letter drawing, figure drawing, and drawing and painting as part of her teaching degree. It was in New York that Martin was first exposed to modern art and began considering a career as an artist. “I thought, if you could possibly be a painter and make a living,” she later said, “then I would like to be a painter. That’s when I started painting.” Art historian Christina Bryan Rosenberger suggests that Martin likely saw exhibitions by Arshile Gorky (1904–1948), Adolph Gottlieb (1903–1974), and Joan Miró (1893–1983) while a student at Teachers College. For the remainder of the war years she continued her wandering way of life, teaching in Delmar, Delaware; Tacoma, Washington; and Bremerton, Washington. No paintings from this period survive.

Martin’s drifting eventually led her to New Mexico in 1946 when, at age thirty-four, she enrolled in a master of fine arts program at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. This was Martin’s first professional training toward becoming an artist. “I went to the universities because. . . there’s a studio to work in and usually in the universities they let you work in the studio any time,” she explained about this period. “And so, I would work at a job and save my money and go to a university when I took a year off to paint. It was the quickest way to get to be painting.”

Martin stayed in New Mexico from 1946 to 1951, and her earliest existing artworks are from these years. In 1947, she participated in the Taos Summer Field School. She exhibited two watercolours at the Harwood Foundation as part of the summer school’s concluding exhibition. This was likely her first exhibition and may have included New Mexico Mountain Landscape, Taos, 1947. After completing her studies, Martin was elected to the faculty of the university in 1948 and executed several encaustic canvases at this time in her role as a teacher of figurative painting. These works include a sympathetic painting, Portrait of Daphne Vaughn, c.1947 of her friend Daphne Cowper, with whom she had a three-year romantic relationship, and Self-Portrait, c.1947, which she gave to her mother in Vancouver. Martin maintained ties to her family throughout her time in the Pacific Northwest and New Mexico, visiting in 1944 and again in 1951 for Malcolm’s funeral. She also spent at least one Christmas in Vancouver in the early 1950s.

Martin lasted only one year teaching at the University of New Mexico, leaving in 1948 for a better-paying job instructing delinquent boys at the John Marshall School in Albuquerque. Along with Cowper, Martin built an adobe house in Albuquerque with the help of her students—the first of several adobe houses that she built throughout her life. She became an American citizen in 1950 and set off on a path to establish herself as an American artist.

A New Direction

In the fall of 1951, Martin embarked on her final period of formal education, enrolling at Teachers College at Columbia University in New York City for a master’s degree in modern art. The ten months that Martin spent in the city had a profound effect on her development as an artist through her introduction to Abstract Expressionism and Eastern philosophy. The Abstract Expressionist art movement had completely transformed the New York art world since Martin left the city in 1943. Its impact was felt throughout the College, where Martin most likely first encountered this key influence.

Martin had several opportunities to see the work of significant artists from the movement. Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) and Ad Reinhardt (1913–1967) both had exhibitions at the influential Betty Parsons Gallery during this period. In addition, Pollock, Mark Rothko (1903–1970) and Clyfford Still (1904–1980) were all included in an exhibition called 15 Americans at the Museum of Modern Art, which also overlapped with Martin’s stay. It was during this time that Martin began to develop an abstract style of her own, which can be seen in a 1952 watercolour, Untitled, which shows an early debt to Surrealism through automatic drawing. The merging of Surrealism and Cubism is often considered the source for Abstract Expressionism in America. Art historian Ellen G. Landau argues that artists were motivated to use “personal means” such as automatism and improvisation, to “attain universal meanings” in their work.

The second key influence that Martin encountered during her short time in New York was an introduction to Eastern philosophy. The lectures of D.T. Suzuki (1870–1966) at Columbia in 1952 were popular and helped introduce Zen Buddhism to American artists like John Cage (1912–1992), Philip Guston (1913–1980), and Reinhardt, among many others. It is not clear whether Martin attended these lectures, but it is possible that her interest in Zen began at this point. She read the Tao Te Ching and practised meditation throughout her life. Her worldview began to be shaped by a mix of Taoism, Zen Buddhism, and Christianity. She later said, “What I’m most interested in are the ancient Chinese like Lao Tse and I quote from the Bible because it’s so poetic, though I’m not a Christian.” Taoist ideas of egolessness and humility can be read in her work and particularly influenced her writing. Martin left New York in 1952 with her master’s degree in hand, transformed by the experience.

After a semester spent teaching in La Grande, Oregon, Martin returned to Taos in 1953. She was now painting in a much more modern style than when she had left New Mexico in 1951. Untitled, 1953, continues the Surrealist manner of Untitled, 1952, that shows the artist’s newfound sense of direction in her art.

In 1954, Martin took a short trip back to New York to attend a seminar at Teachers College. During this visit she took the first steps toward a professional career as a painter. She visited galleries and absorbed the current trends, just as she had in 1951, and approached Betty Parsons (1900–1982), who was famous among artists for introducing the first generation of Abstract Expressionist painters. During the late 1940s and early 1950s Parsons exhibited the work of Pollock, Rothko, Still, and Barnett Newman (1905–1970). She encouraged Martin to dedicate herself to painting full-time.

Upon returning to Taos, Martin applied to the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation for financial support. Her application cited a promised exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery, although such an exhibition would not materialize for another four years. She was awarded a monthly grant of forty dollars, which enabled her to concentrate on her painting without the need to teach. She began to take an approach to her art that incorporated organic shapes and forms such as in Untitled, 1955. This work typifies what has been called her biomorphic period. However, Martin was unsatisfied with these early attempts at abstraction, later saying,

“I worked for twenty years becoming an abstract painter. . . . I never wanted to show my work. I never wanted to sell it, because it was not what I wanted, and I knew that it was not what I was supposed to be doing.”

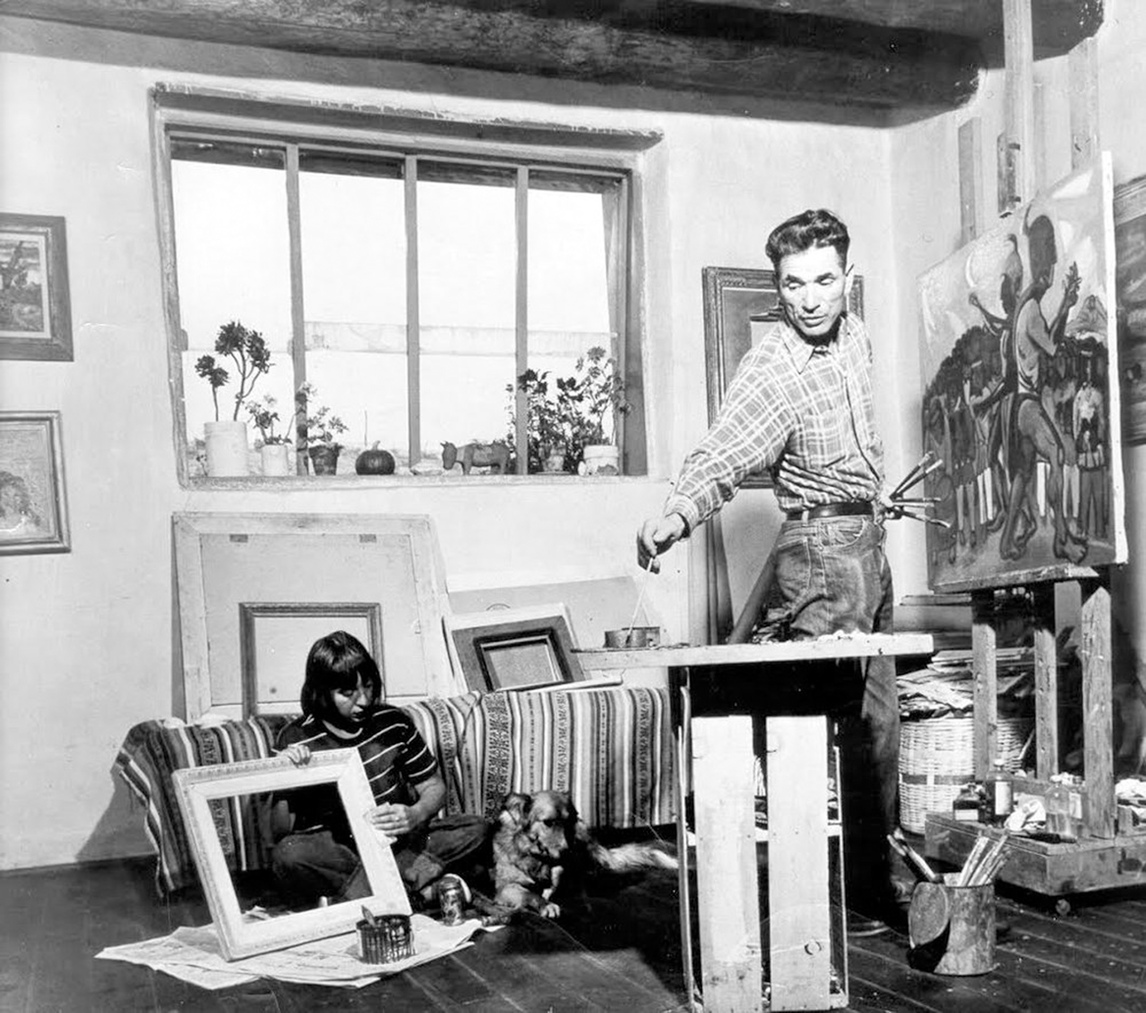

In spite of Martin’s negative attitude toward this period, her biomorphic work brought her first success, which included museum exhibitions and sales. By 1955 she was included in various group exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in Albuquerque and the art gallery of the Museum of New Mexico, as well as in two local commercial galleries. That same year Martin was awarded a two-person show with Emma Lu Davis (1905–1988) at the art gallery of the Museum of New Mexico. Owing to a 1956 exhibition at the Jonson Gallery in Albuquerque, Martin became associated with the Taos Moderns group. Artists Beatrice Mandelman (1912–1998), Louis Ribak (1902–1979), Edward Corbett (1919–1971), and Clay Spohn (1898–1977) kept abreast of advances in American art through their connections in New York and San Francisco and represented the more modern painters working in New Mexico at the time. In 1956 Martin sold a painting to Parsons, and then another the following year, at which time Parsons offered Martin an exhibition at her New York gallery.

Success and Challenges

The decade that Martin lived in New York City between 1957 and 1967 brought her remarkable career success, but it also presented her with many personal challenges. On the one hand, she was finally able to establish herself as a professional painter, a goal since the mid-1940s, and her work flourished in the New York scene. But on the other, the wandering life that she had been living more or less since she left Vancouver showed no sign of abating and her struggles with her mental health, which were likely present for some time before moving to New York, came to the forefront.

Martin’s New York story, with all of its complications, started with Betty Parsons. As a condition of representing her, Parsons told Martin that she had to move back to New York. “Betty bought enough paintings so that I could afford to go,” Martin explained. “She wouldn’t show my paintings unless I went to New York and lived.” Parsons also provided Martin with an entrance into the New York art scene. Through Ellsworth Kelly (1923–2015), another of Parsons’ artists, Martin found a loft on Coenties Slip, an area of abandoned sail lofts and ship chandleries along a triangular three-block area of the East River on the southeastern edge of Manhattan. It was an artist’s refuge. Aside from Kelly, other residents of Coenties Slip included Jack Youngerman (b.1926), Robert Indiana (1928–2018), Lenore Tawney (1907–2007), and James Rosenquist (1933–2017). Jasper Johns (b.1930) and Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008) lived around the corner on Pearl Street.

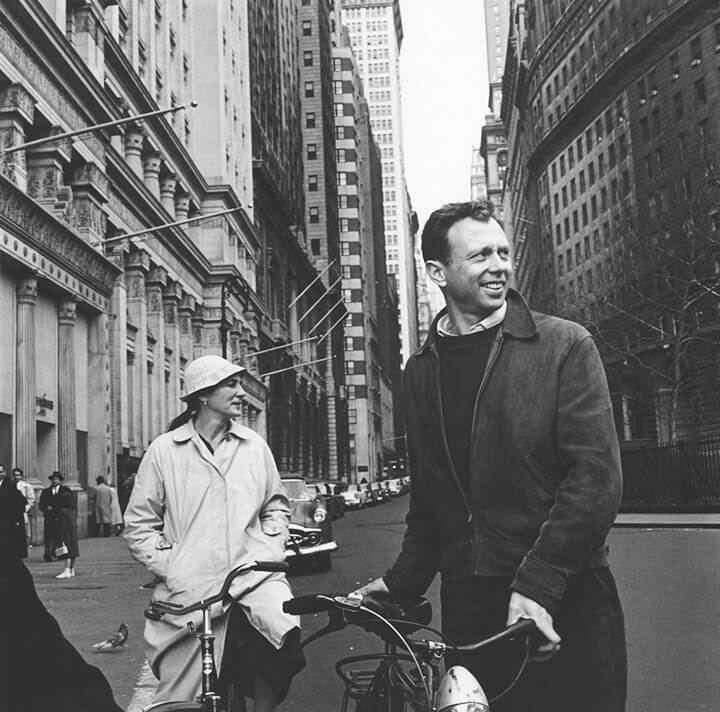

Martin first lived at 27 Coenties Slip, right on the river’s edge, with an expansive view of the ships passing below, and moved two years later to 3-5 Coenties Slip. She was so close to the harbour that she “could see the expressions on the faces of the sailors.” Martin lived on or around Coenties Slip until she left New York in 1967 and maintained close friendships with several artists who lived nearby. A 1957 photograph by Hans Namuth shows Martin at ease in Kelly’s studio, and in another from 1958 she is out with Kelly and Indiana on bikes. She also made close female friendships at this time with the writer Jill Johnston (1929–2010) and artist Ann Wilson (b.1935), as well as Tawney. Even though these relationships were very positive for Martin, she also described this as a lonely period: “We all knew enough to mind our own business—even when we stopped painting. . . so I used to go to the Brooklyn park and museum. And so did everyone else on the Slip. But we all went by ourselves.” This was the contradiction of Martin’s New York period; she was thriving professionally and struggling personally all at once.

At the same time that Martin found her place as an artist on the Slip, another community was burgeoning there. Art historian Jonathan Katz referred to Coenties Slip around 1960 as “one of America’s only largely queer artistic enclaves” and speculates that Martin was romantically involved with Tawney during this time. Henry Martin, whose 2018 biography of Martin was the first to explore her relationships with women in depth, calls Katz’s often-repeated claim into question, identifying Betty Parsons and an artist known as Chryssa as Martin’s romantic partners in this period. Whatever the case, Martin seems to have left the queer social world behind when she left New York in 1967. Despite sharing several meaningful and long-term relationships in Oregon, New Mexico, and New York City, Martin never specifically acknowledged her sexuality in interviews or writings during her life. Martin kept her sexuality hidden, often even from close acquaintances. Donald Woodman, who knew Martin in the 1970s and 1980s, for example, was not aware of whether she was a lesbian.

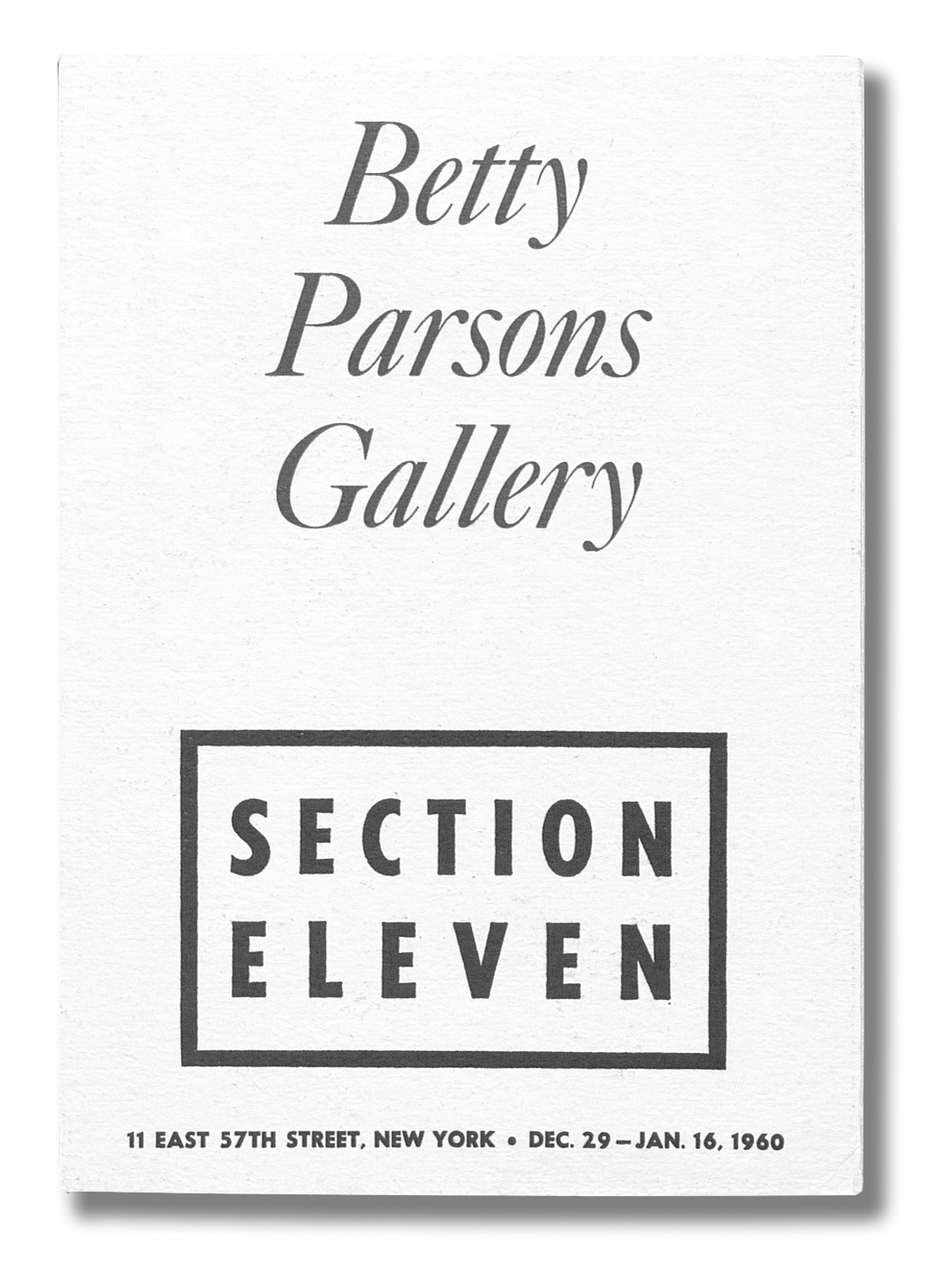

Martin’s first exhibition in New York was as part of Section Eleven, an extension of Betty Parsons Gallery dedicated to new talent, and ran from December 2 to 20, 1958. By the time Martin had moved back to New York in 1957, many of the most famous of the Abstract Expressionists had moved on to more commercially successful galleries, with the exception of Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt. Section Eleven was an effort by Parsons to rejuvenate her gallery by introducing “gifted but as yet unknown painters.”

Despite Martin’s success in New Mexico, Parsons promoted the artist as her discovery. A review of Martin’s second exhibition at Parsons in December 1959 referred to her dismissively as a “specialist in teaching children creative activities.” New York Times critic Dore Ashton, on the other hand, noted Martin’s New Mexico history in her review of the 1958 exhibition: “Agnes Martin, whose talent was seasoned on the New Mexico desert, is exhibiting her oils for the first time in New York.” Setting a tone for how Martin’s work would be framed for the rest of her career, Ashton closed the review by writing that the paintings “seem to be the observed and deeply felt essences of the mesa country, so long Miss Martin’s home.”

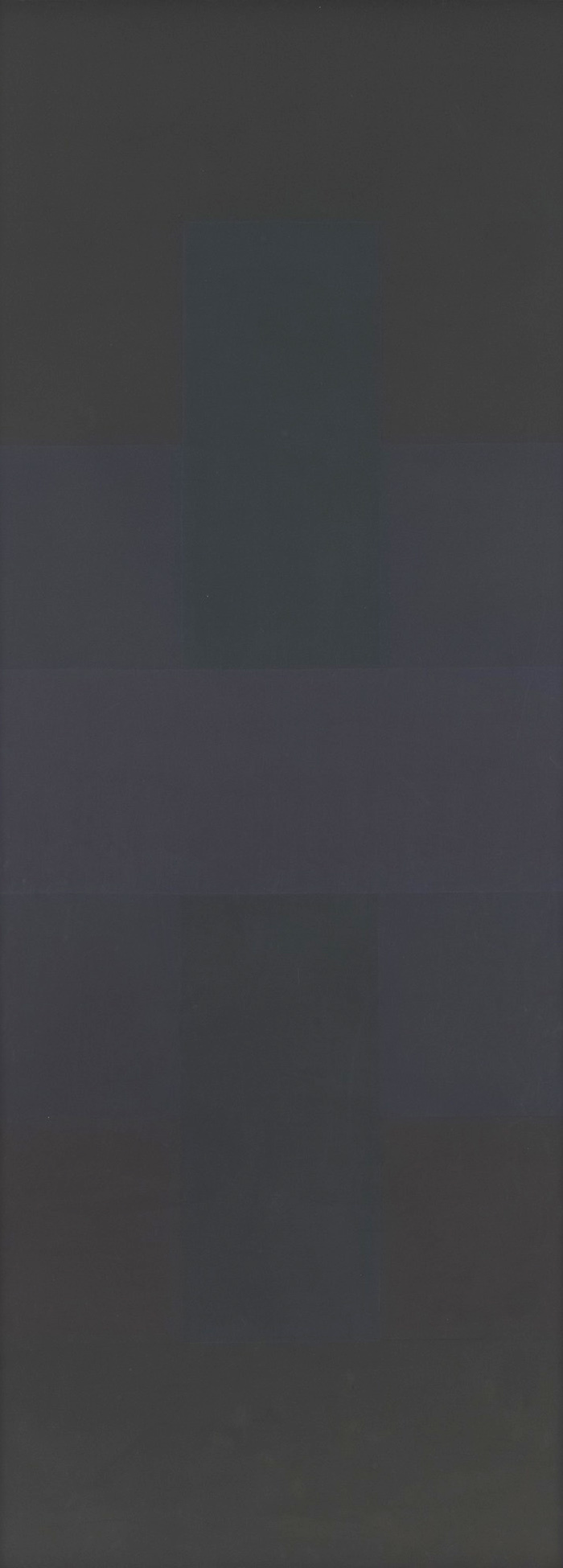

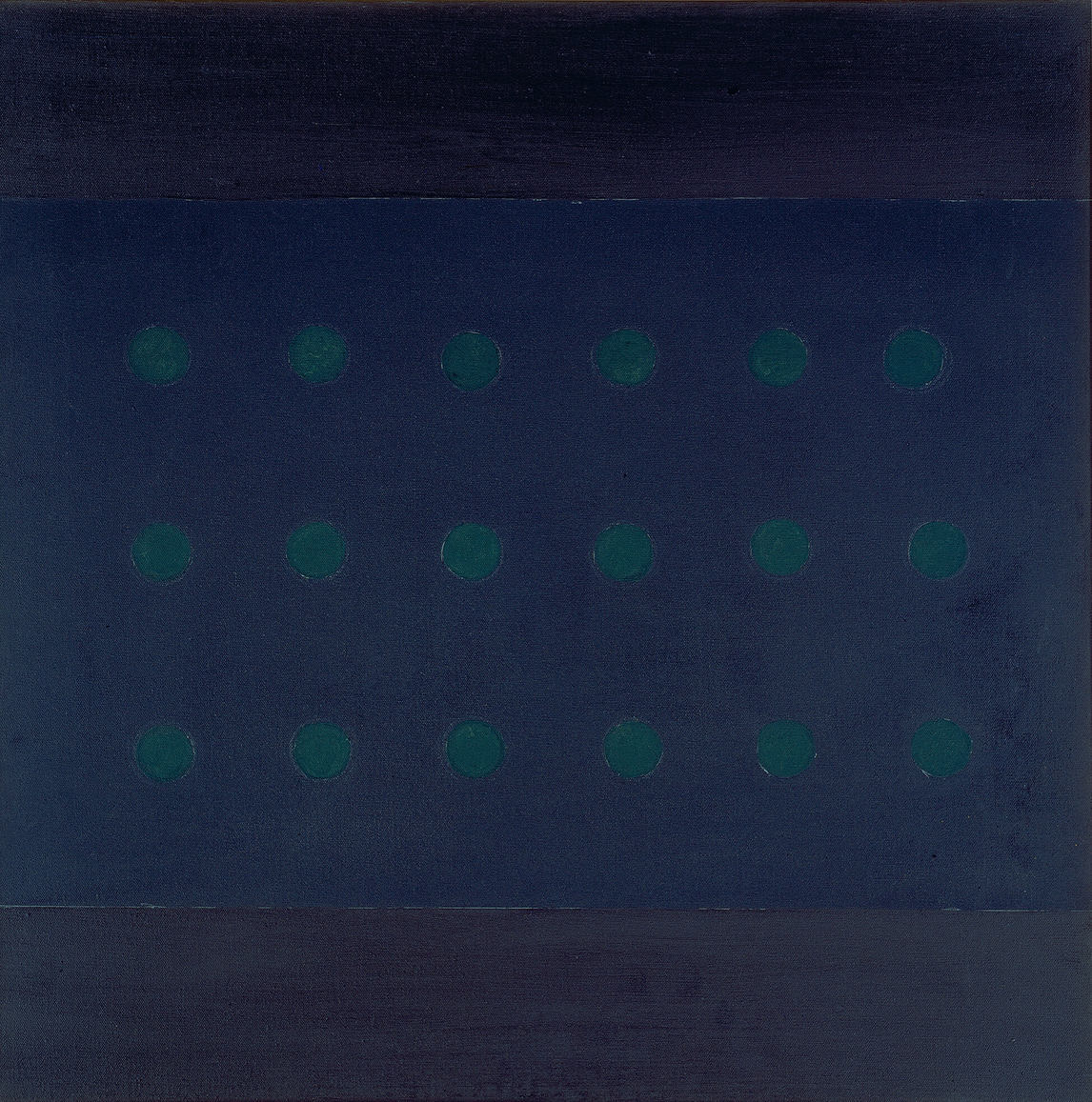

In addition to her connection to Betty Parsons, Martin’s association with Ad Reinhardt and Barnett Newman during this period represented perhaps her strongest connection to the generation of American Abstract Expressionists whose work had so influenced the culture at Teacher’s College while she was a student there in 1951 and 1952. Reinhardt and Martin’s friendship may have begun as early as 1951, when he visited Taos at the invitation of Taos Moderns members Edward Corbett and Clay Spohn, and lasted until his death in 1967. Martin greatly admired his paintings. Reinhardt advocated for what he called purity in abstraction, and his influence on Martin can be seen in her simplified 1957 canvases such as Desert Rain when compared to his own Abstract Painting from the same year.

Agnes Martin, Desert Rain, 1957, oil on canvas, 63.5 x 63.5 cm, private collection. © Agnes Martin / SOCAN (2019).

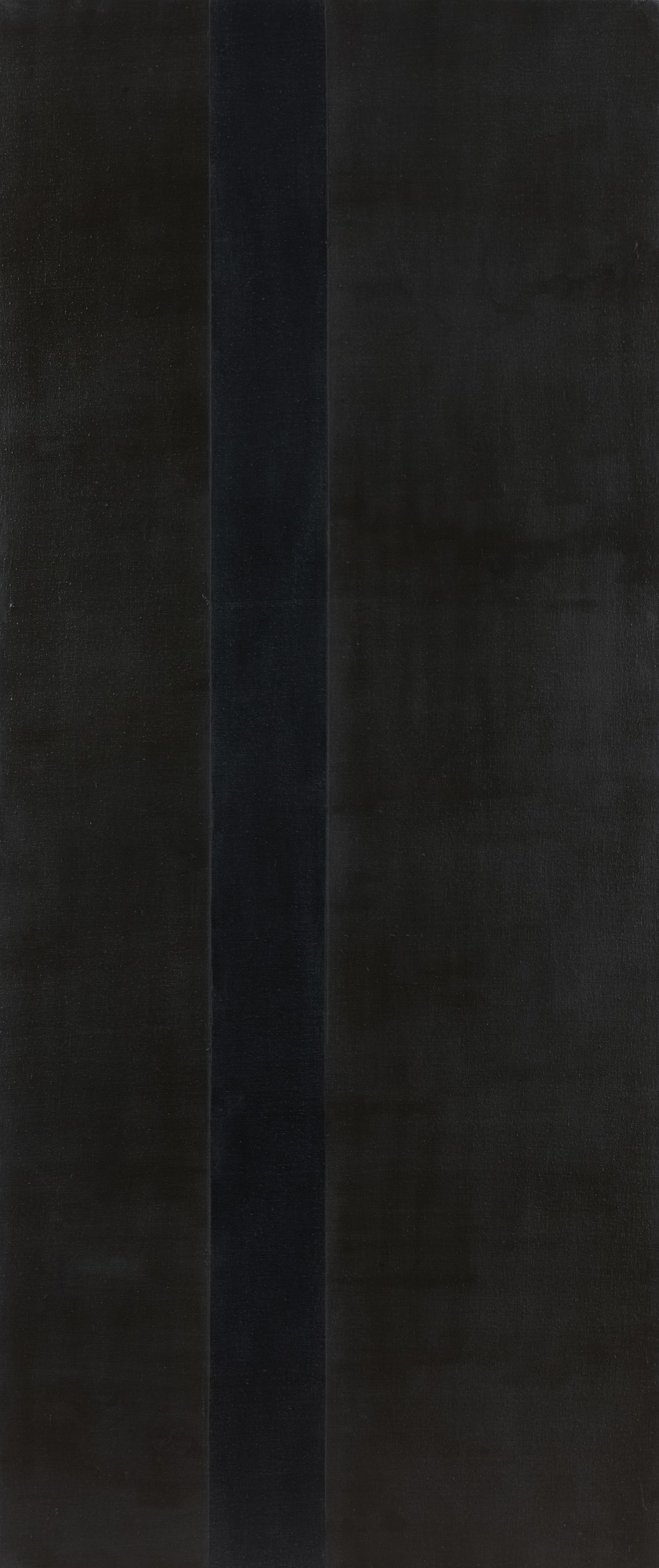

Martin and Newman were introduced in 1958, and he helped Martin hang her first exhibition at Parsons. The two artists developed a close friendship. Newman’s influence can be seen in the use of hard edges in Martin’s work at this time. A comparison of Martin’s Night Harbor from 1960 with Newman’s Abraham, painted in 1949 but included in the exhibition The New American Painting at the Museum of Modern Art in May 1959, shows similar colours and formats.

Reinhardt and Newman’s influence connect Martin to the legacy of Abstract Expressionism, a lineage that she asserted for the remainder of her life. “The most important cluster of painters in history was the American Abstract Expressionists,” she wrote in 1983. “They gave up defined space (which resulted in enormous scale) and they gave up forms as expressive in themselves and they gave up all objectivity, making an authentic abstract art possible.” However, Martin was also part of the generation of New York artists—including Indiana, Johns, and Rauschenberg—who usurped Abstract Expressionism’s dominance. This can be seen, for example, in Martin’s experimentations with assemblage between 1958 and 1961, which call to mind what these three artists were doing at the same time.

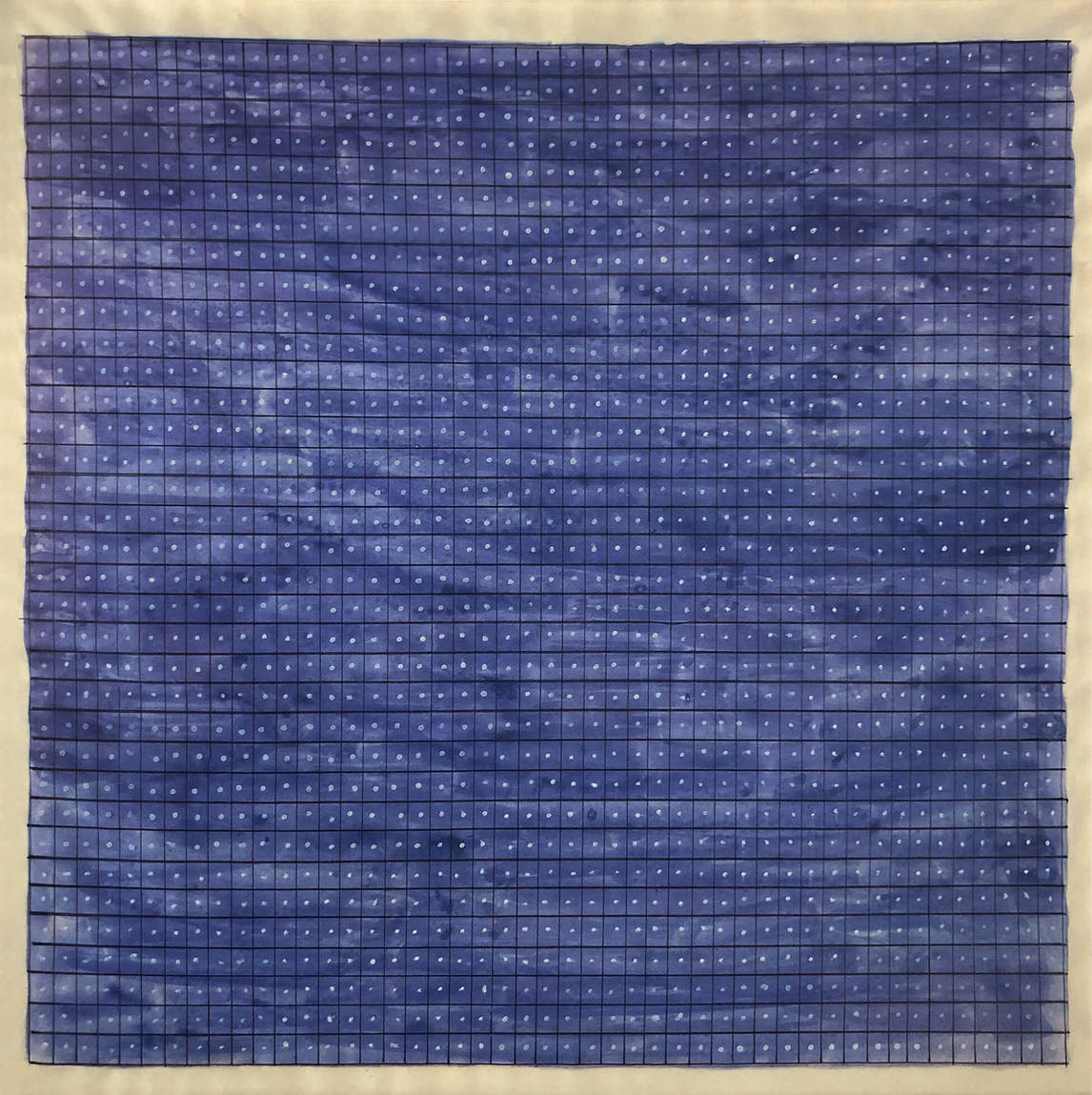

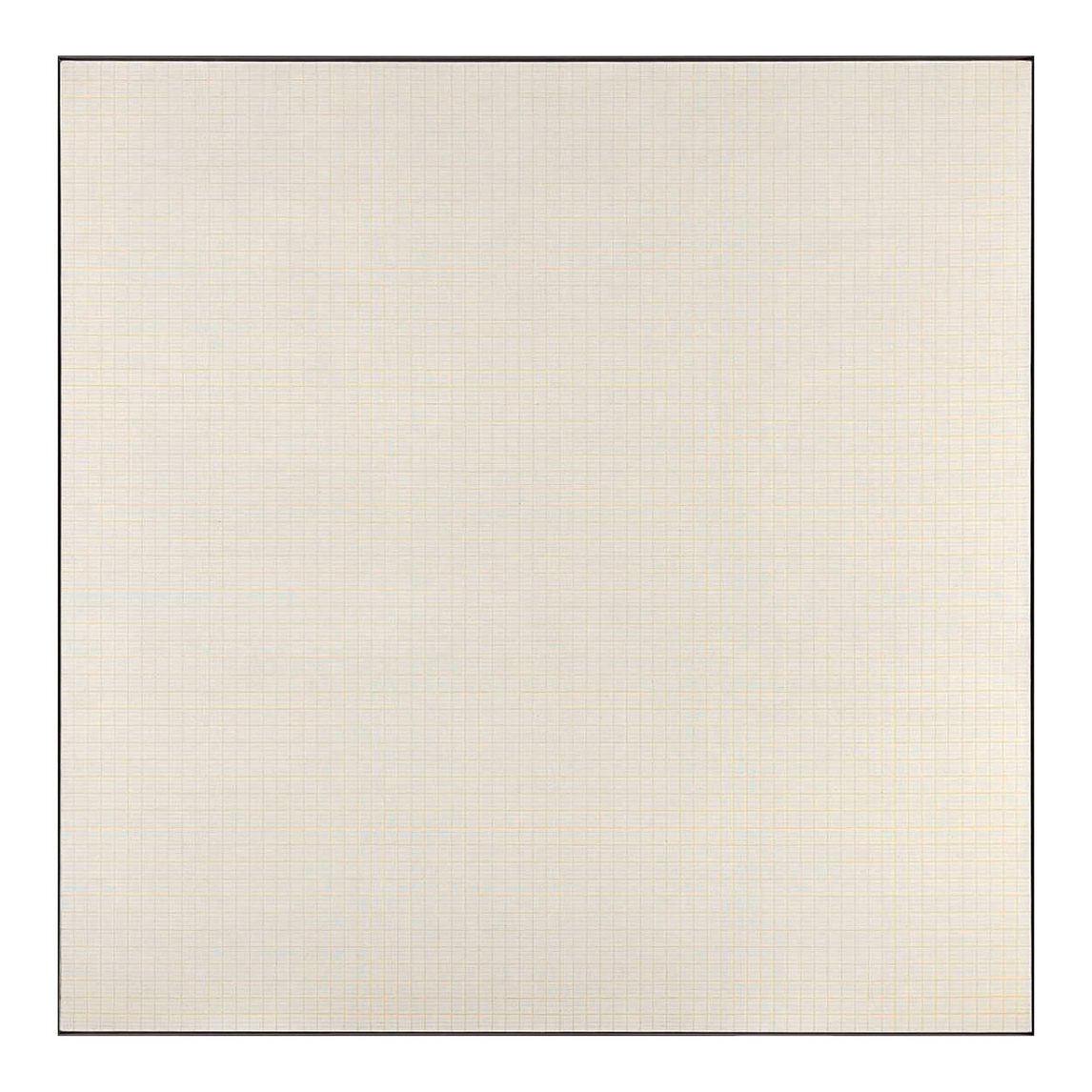

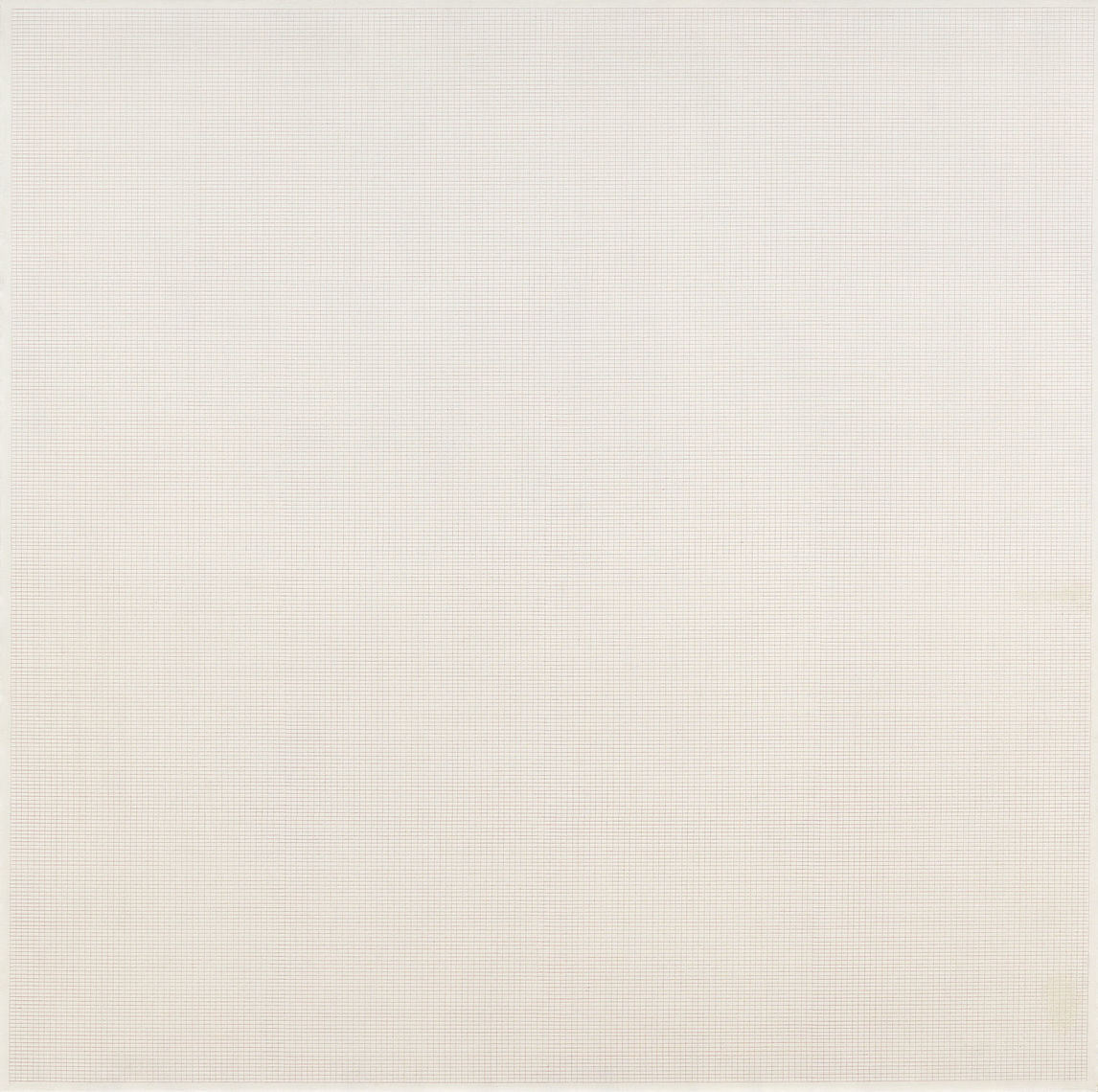

Martin premiered her first grid paintings in 1961 in her third and final exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery. The exhibition included White Flower, 1960, and The Islands, 1961, two paintings that established a formal vocabulary that Martin mined for the rest of her life: a square canvas, horizontal and vertical composition, and total non-representation. The grid was a recurring format in non-objective painting by many artists in the late 1950s and through the 1960s. The art historian Rosalind Krauss identified Jasper John’s Grey Numbers, 1958, as an early example of the grid being employed in the New York City context. Many of Martin’s paintings from 1958 and 1959, such as The Laws, Buds, and Homage to Greece, include grid-like elements. Martin never acknowledged these precedents, offering instead a much more personal origin story: “I was thinking about innocence, and then I saw it in my mind—that grid,” she told critic Joan Simon.

The grid offered Martin a conduit to a completely formless way of painting. “Not abstract from nature, but really abstract. It describes the subtle emotions that are beyond words, like music, you know, represents our abstract emotions,” she later explained. Finding the grid also represented a culmination of sorts for Martin and started her on the path of repudiating much of her earlier work. “When I got the grids, and they were completely abstract, then I was satisfied,” she maintained, continuing, “I consider that the beginning of my career. The ones before I don’t count. I tried to destroy them all, but I couldn’t get some of them.”

After three solo exhibitions with Parsons Gallery, Martin switched to Robert Elkon Gallery in 1962, where she showed four times in the 1960s. Between 1962 and 1966 her work was shown in all three major New York-based modern art museums: Geometric Abstraction in America at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1962; The Responsive Eye at the Museum of Modern Art in 1965, and Systemic Painting at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1966. Her painting The City (1966) was illustrated in the review of Systemic Painting by Artforum in November 1966.

Coinciding with this period of professional success, Martin was in a difficult mental state. She suffered at least two acute episodes of schizophrenia during this time, both of which resulted in her hospitalization. She likely struggled with schizophrenia for most of her adult life, but it is undocumented before 1962. The first incident occurred when Robert Indiana found Martin wandering on South Street. She was picked up and committed to Bellevue Hospital in New York and subjected to electroshock. Her artist friends from Coenties Slip came together to help find her treatment with a respected art-collecting psychiatrist. In 1965, Martin embarked on a solo around-the-world steamer ship holiday. In July she wrote a letter to Tawney, “I have been wishing every day that I had been writing to you but the fact is that I have been absolutely overwhelmed by this trip, especially Pakistan and India.” She was hospitalized after entering a trance in India, and Tawney travelled there to help bring her back to the United States. There are several more debilitating schizophrenic attacks recorded after Martin left New York, but the true extent of the disease’s effect on her life is not known.

In late 1967 Martin suddenly, and dramatically, left New York. By all indications she intended to leave painting behind as well: Martin burned all of the art left in her studio and gave away her art supplies. Exactly why Martin left New York just when she had finally established the career that she had been pursuing for two decades has been the topic of much conjecture. It is often attributed to Ad Reinhardt’s death or the fact that her studio was being torn down. Martin never gave a straightforward answer to this question, offering instead equivocations such as, “I thought I would experiment in solitude, you know. Simple living.” Later, she explained, “I had established my market and I felt free to leave.” In another instance, she wrote, “I left New York in 1967 because every day I suddenly felt I wanted to die and it was connected with painting. It took me several years to find out that the cause was an overdeveloped sense of responsibility.”

Leaving New York

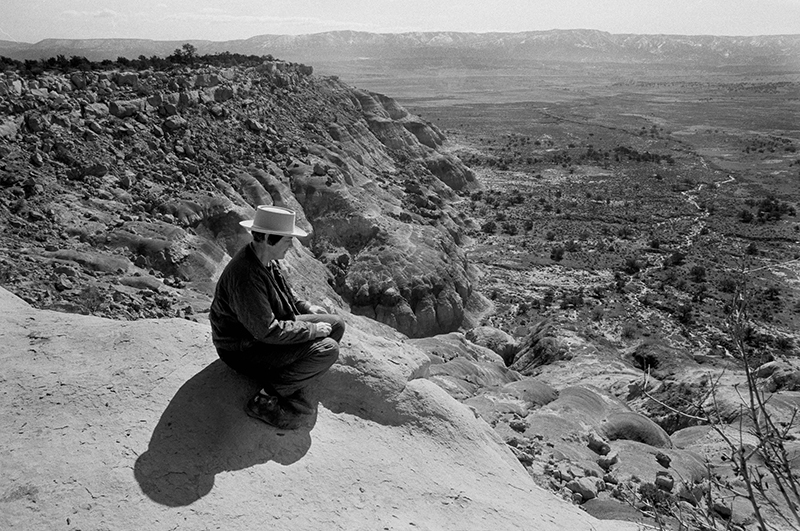

Martin used the proceeds from a $5,000 grant from the National Council for the Arts to purchase a Dodge pickup truck and an Airstream trailer, and spent the next year and a half camping in Canada and the western United States. The exact itinerary of the trip is not known in detail. She spent time exploring nature and visiting with her family in Vancouver. She told Suzan Campbell that she drove all over the continent: “I drove all in the West and up in Canada and couldn’t make up my mind where to stop.” She spent much of the time alone, but not all of it. She was joined by Lenore Tawney for two weeks of camping in California and Arizona, before striking off alone to the Grand Canyon, and ultimately back to New Mexico. “I had a vision of an adobe brick,” she said. “And I thought, that means I should go to New Mexico.”

Returning to New Mexico in 1968 for the first time in more than a decade, Martin did not settle in Taos or Albuquerque where she had previously lived, but continued her pursuit of solitude. One day Martin pulled into a gas station on the Mesa Portales near Cuba, New Mexico, in an isolated northwestern part of the state separated from Santa Fe and Taos by the Jemez Mountains. “I asked the manager if there was anybody that he knew who had land outside of town with a spring. And he said, ‘Yes, my wife does.’ She had 50 acres on top of this mesa.”

Martin leased the fifty acres and lived there in her trailer while she started building an adobe house as she learned to do in Albuquerque in 1947. During this time she developed an ascetic lifestyle. She had no access to electricity, plumbing, or a telephone. Her bathtub was outside, and was filled by cold well water in the morning and warmed by the sun for a bath. She heated her home with and cooked on a cast iron wood stove. One winter Martin survived on walnuts, cheese, and tomatoes, while another she ate only gelatin mixed with orange juice and bananas.

Most importantly, Martin did not paint. Around 1971 she explained this to her friend, New York art collector Sam Wagstaff (1921–1987), in a letter, writing:

“I don’t understand anything about the whole business of painting and exhibiting. I enjoyed it more than I enjoyed anything else but there was also a ‘trying to do the right thing’—a kind of ‘duty’ about it. Also a paying of the price for that ‘error’ that we do not know what it is. What we ‘owe.’ Now I do not owe anything or have to do anything. Fantastic but even more fantastic I do not think that there will be any more people in my life.”

Over the next nine years Martin built five buildings on the property. “I’m just interested in building with native materials. Adobe bricks and these logs they call vigas and I built some log houses, too.” Although she left painting behind, Martin never stopped the business of being an artist, arranging loans for exhibitions and sales through her galleries as well as collectors like Wagstaff.

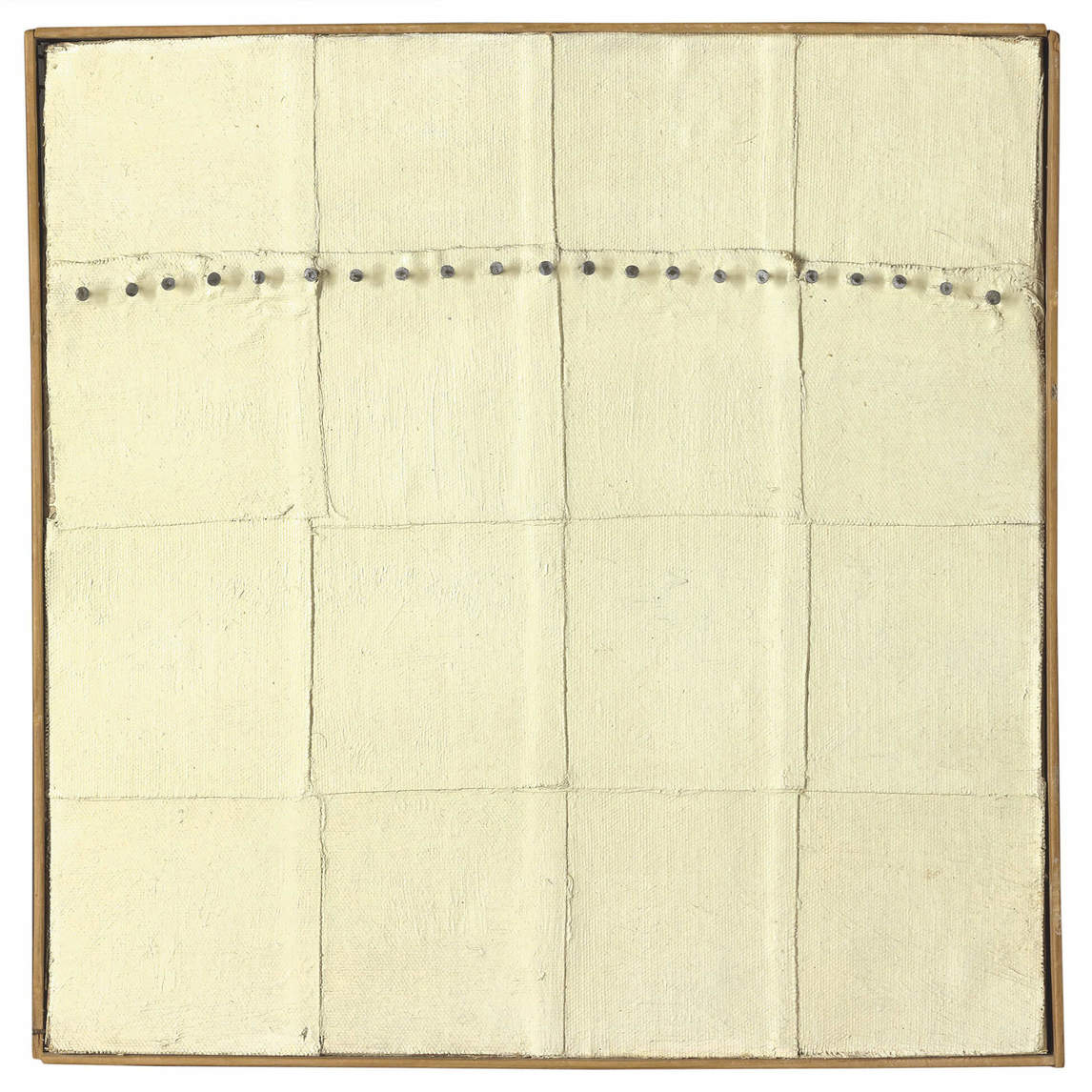

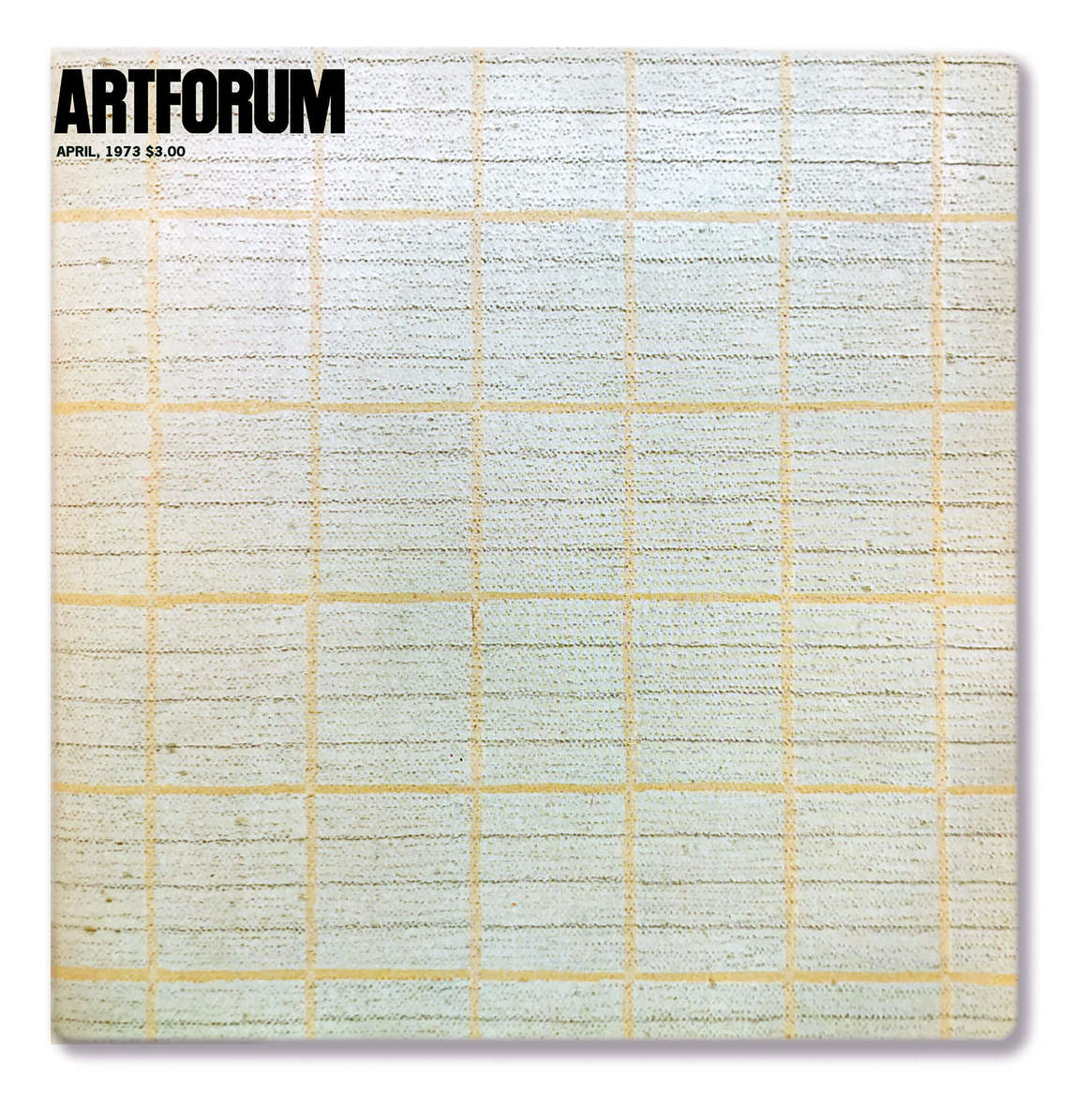

Referring to her ten years in New York, Martin told her friend Jill Johnston, “I had 10 one-man shows and I was discovered in every one of them. Finally when I left town, I was discovered again—discovered to be missing.” It did not take long for Martin to be “discovered to be missing” after moving to Mesa Portales. Curator Douglas Crimp (1944–2019) visited in 1971 as part of his effort to organize Martin’s first ever non-commercial solo exhibition, a modest show at the School of Visual Arts in New York in April 1971. The following year Ann Wilson, her friend from Coenties Slip, visited Portales to work with Martin on the catalogue for her first retrospective exhibition, curated by Suzanne Delehanty (b.1944) at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania. The exhibition featured thirty-seven paintings, twenty-one drawings, and fourteen watercolours, all from between 1957 and 1967. Although Martin was not making any new paintings at this point, she travelled to Germany in 1971 to produce a suite of thirty screen prints, titled On a Clear Day. She was also included in Harald Szeeman’s documenta 5 with four paintings on loan from Wagstaff. This renewed interest in Martin’s work led to two articles on the artist in the April 1973 issue of Artforum, which also featured her Orange Grove, 1965, on its cover. The same issue of Artforum included a short piece written by Martin herself, titled “Reflections.” Around this time Martin began writing and delivering lectures about her work. She included a transcript of a lecture she delivered at Cornell University in 1972 in the catalogue for her 1973 exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, alongside three short creative pieces that can best be described as parables. With titles such as The Untroubled Mind and The Still and Silent in Art, these idiosyncratic texts outline a deeply personal approach to painting.

Return to Painting

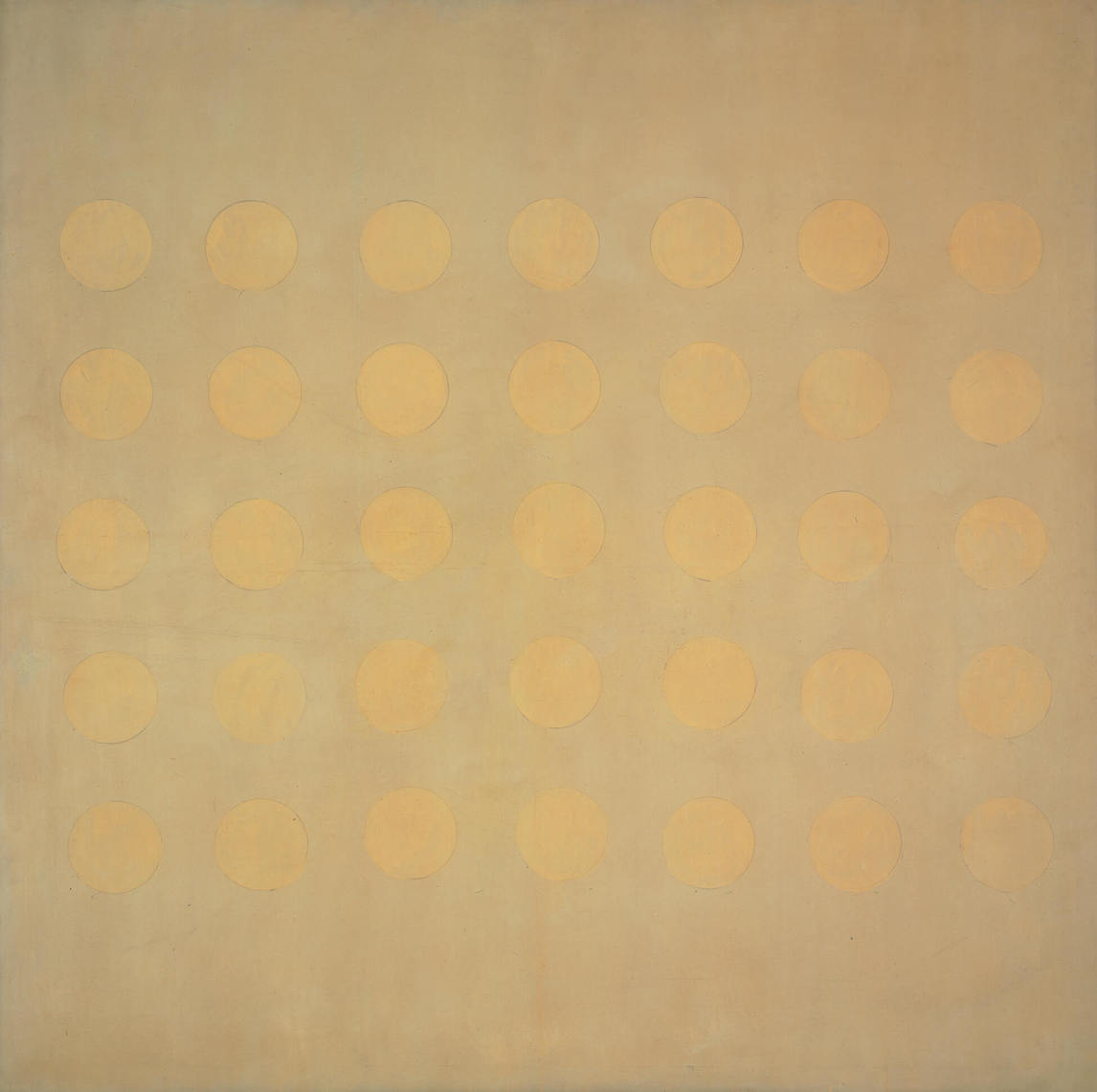

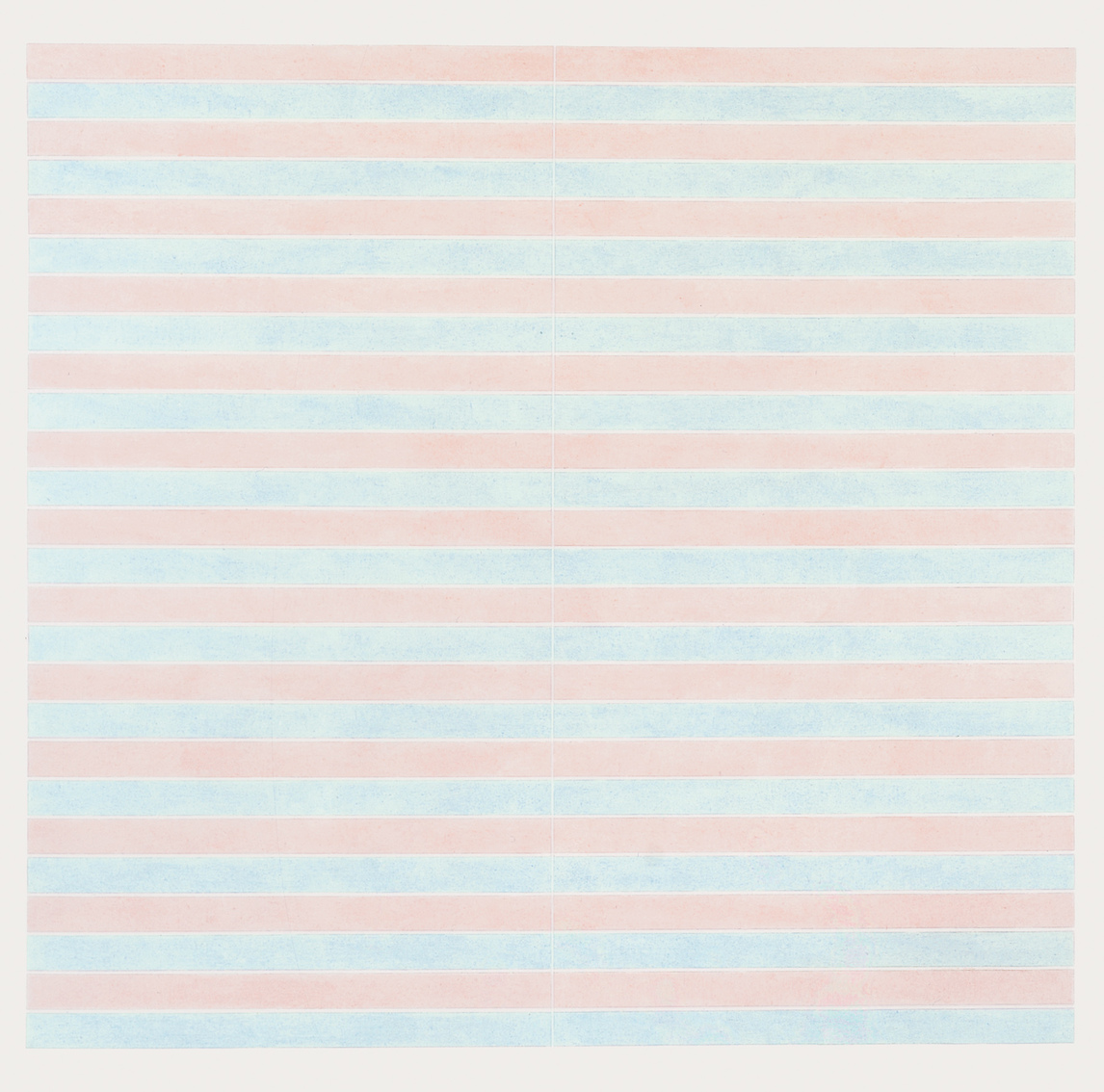

In 1974 Martin discovered a new mode of expression that she would continue to communicate for thirty more years. She began by building a thirty-five-foot-square log-cabin-style studio on the Portales property and began to paint again. When she had enough canvases, she travelled to New York to seek out Arne Glimcher (b.1938) at Pace Gallery. He soon visited her in New Mexico and the canvases that Martin showed him were a departure from the New York grids. She maintained the six-foot-square scale, but the grid had been replaced with vertical and horizontal bands of ochre and blue, such as in Untitled #3, 1974. She soon dropped the vertical bands and focused almost exclusively on horizontal bands of alternating sizes and colours. Martin’s first exhibition at Pace Gallery opened on March 1, 1975, and Glimcher represented her for the rest of her life.

Another departure for the sixty-four-year-old artist—one that attests to her continuing curiosity—is the feature-length film Gabriel, 1976. Over three months in 1976, Martin filmed a local boy wandering through the landscapes of California, Colorado, and New Mexico. The film is mostly silent but intermittently scored with Bach’s Goldberg Variations, a musical work made famous in 1955 by Canadian pianist Glenn Gould (1932–1982). Martin used the film to explore the themes of beauty, happiness, and innocence, which had appeared in her painting since the 1960s. “I made a movie in protest against commercial movies that are about deceit and destruction,” she said in 1996. “My movie is about happiness, innocence and beauty. I just wanted to see if people would respond to positive emotions.” Martin also attempted a second film, a more complicated affair called Captivity that included dialogue, a script, and Kabuki actors hired from San Francisco. Captivity was shot in New Mexico and the final scene was filmed in the Japanese garden at Butchart Gardens outside Victoria, British Columbia. Unlike Gabriel, Captivity was never completed.

After just under ten years on Mesa Portales, a dispute with the family who owned the land arose, and Martin had to leave her home and studio behind. “I had a lifetime lease from Mrs. Montoya,” she told Eisler, “then her brother came and said I was on his land. And I was. He had a ruthless lawyer, who said he would sue me for anything I took off. I lost a couple of trucks.”

The Final Years

In 1977, Martin moved to a rented property in Galisteo, a small town south of Santa Fe, much closer to society than she had been in Portales. She brought her Airstream trailer and covered it in adobe bricks. Martin set about building a house and studio and in 1984 she purchased the property. At seventy-two, she owned her own home and property for the first time. Although Martin was experiencing material success, she still maintained an austere lifestyle; one of her few public indulgences was a white Mercedes that Arne Glimcher had given to her, which she drove around New Mexico well into her nineties. “I have tons of money,” she told Eisler, “anybody that shows with Arne Glimcher makes plenty of money, and I’ve made millions. It doesn’t mean a thing to me. All I want is a good car.” With financial success, Martin was also able to travel extensively. Beginning in the 1970s she visited many international locations, including Panama, Germany, Iceland, Sweden, and returned several times to her native Canada. In 1975 and again in 1978, she travelled to Great Slave Lake and the Mackenzie River in the Northwest Territories. In 1989 she took a cruise up the coast of British Columbia and Alaska. And in 1995 she took a train across the country, from Vancouver to Halifax and back to Montreal.

Martin participated in the Venice Biennale in 1976, 1978, 1980, 1997, and 2003; was the subject of retrospective exhibitions at the Hayward Gallery in London in 1977, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1991, and the Serpentine Galleries in London in 1993; and was awarded the Golden Lion for Lifetime achievement in 1997. After being ignored by Canadian museums through the 1950s and 1960s, her work finally received recognition in the country of her birth. The Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto purchased Untitled #8, 1977, in 1977 and The Rose, 1964, in 1979, although she did not have her first solo Canadian exhibition until 1981. The twelve-canvas piece The Islands I–XII, 1979, was exhibited at the Glenbow Museum in Calgary and the Mendel Art Gallery (now the Remai Modern) in Saskatoon in 1981 and at the Saidye Bronfman Centre in Montreal in 1982. The most significant exhibition from her late period was a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, curated by Barbara Haskell in 1992. Like Martin’s retrospective at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia nineteen years before, Haskell’s exhibition featured only artworks made after Martin’s move to New York in 1957, ignoring (at Martin’s request) anything made in New Mexico in the 1950s. It was not until 2012, seven years after her death, that an exhibition and publication explored Martin’s pre-1957 work.

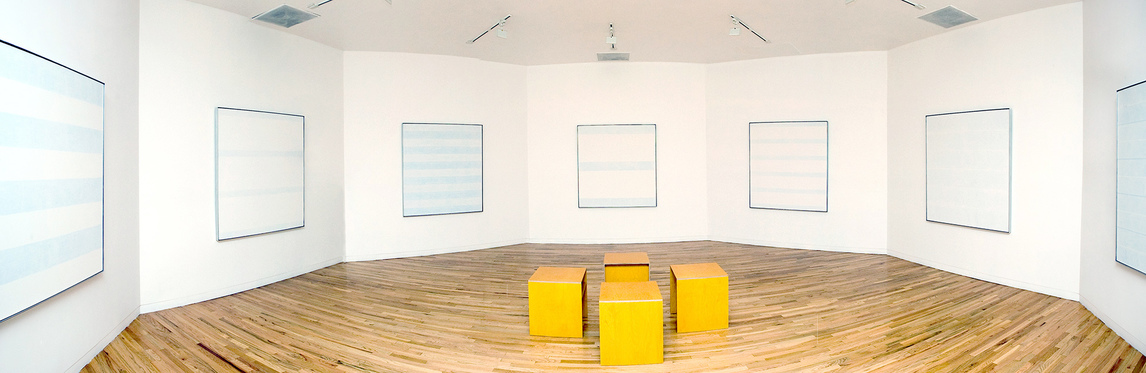

While the 1980s were a critically and financially successful decade for Martin as well as one of the most stable periods of her life, she continued to cope with mental illness. She received treatment in the early 1980s at both the state mental hospital in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and at St. Vincent Hospital in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Around the same time as her retrospective opened at the Whitney Museum, Martin moved into a retirement residence in Taos, but she did not retire from painting or exhibiting her work. She kept her home and studio in Galisteo but also opened another studio in Taos, where she worked most days. She reduced the size of her six-foot-square paintings to five feet square, which were easier to handle. She also maintained an ambitious travel schedule and continued to drive. In 1997, Martin donated a series of seven paintings to the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, where they are on permanent display in a custom-built, octagonal gallery. The canvases are illuminated by natural light from a central oculus over four yellow benches designed by her friend and fellow artist Donald Judd (1928–1994). The gallery invites quiet contemplation and has been compared to the Mark Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas. Martin put some of her new wealth into philanthropy, often directed toward youth, sports, and nature conservation in and around Taos.

Martin never stopped experimenting within the confines of her post-grid style and in 2003 produced her first non-horizontal or vertical canvases since the early 1960s, including Homage to Life, 2003, and Untitled #1, 2003. She was honoured by the United States and Canada near the end of her life; she was presented with the National Medal of Arts by Bill and Hillary Clinton in 1998 and joined the Royal Canadian Academy of the Arts in 2004. That summer Martin’s health began to decline, forcing her to stop painting. She died in Taos on December 16, 2004, of congestive heart failure. Her ashes were spread on the grounds of the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos. She believed that “art is the concrete representation of our most subtle feelings.” By that measure, Agnes Martin was one of the great artists of the twentieth century.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements