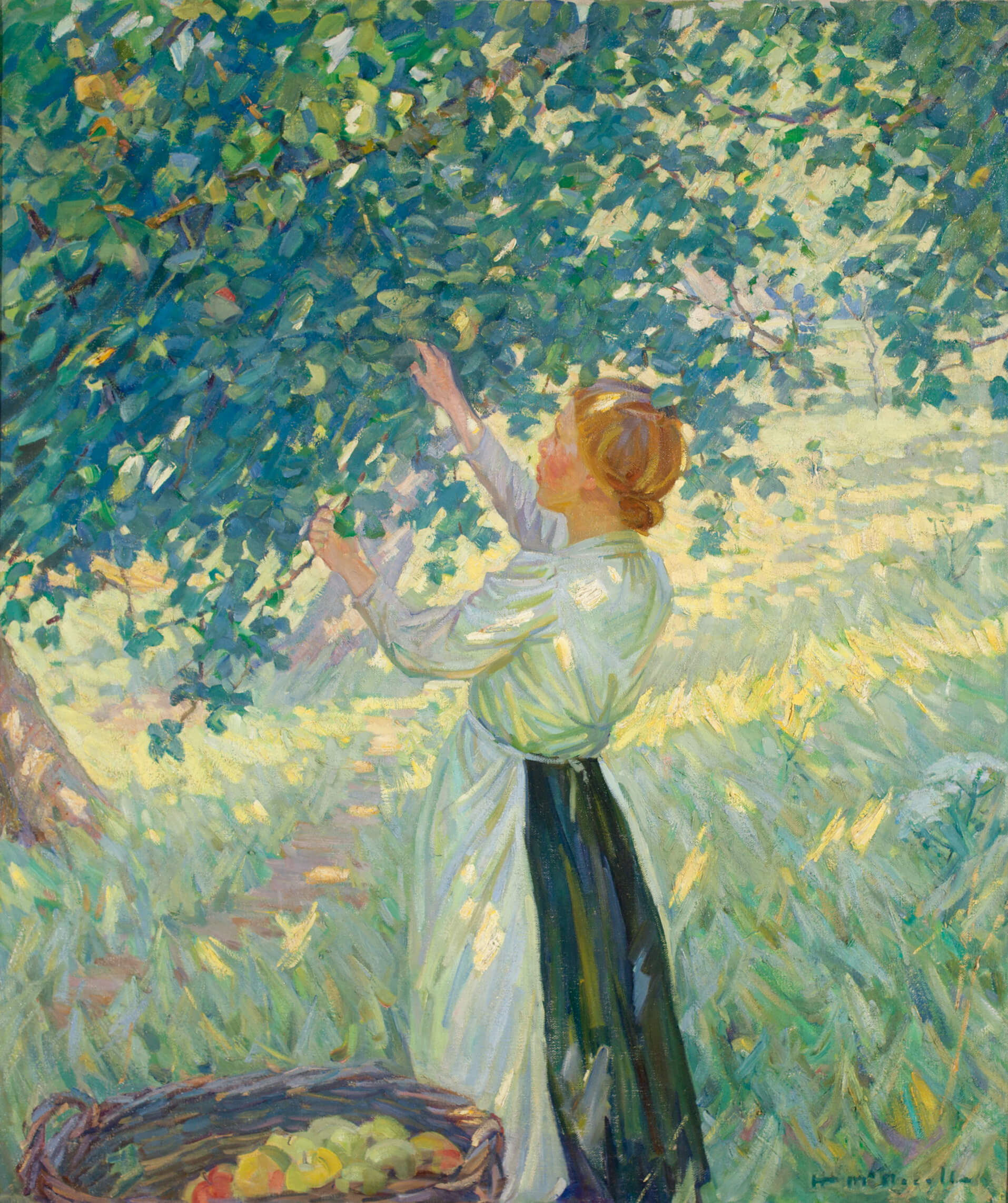

The Apple Gatherer c. 1911

Helen McNicoll, The Apple Gatherer, c. 1911

Oil on canvas, 106.8 x 92.2 cm

Art Gallery of Hamilton

Among the largest of McNicoll’s canvases, The Apple Gatherer joins The Little Worker, c. 1907, as a representation of rural female labour that neither romanticizes nor pities its subject. The central figure reaches to pluck an apple; one hand pulls a branch out of the way as the other stretches into the tree. The target apple itself is just a hint of red, hidden among the green and yellow brushstrokes that make up the leaves. The woman, wearing a long apron, is in the midst of her labour: her pose, arms in the air, back curved uncomfortably, would have been hard to sustain and will make her body ache at the end of the day. (Perhaps this was true of the model’s labour as well.) She has been at her work for a while, as her basket is nearly full and her cheeks are flushed with sunburn.

Peasant subjects were popular in the later nineteenth century, especially with a middle-class, urban audience that felt nostalgic for the pre-industrial age. This imagery also helped to shape the contemporary understanding that the physical appearance of the body revealed a person’s social class. While not as political in intent as other artists who took up the subject of rural labour—Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) or Jean-François Millet (1814–1875), for example—McNicoll’s unsentimental images of rural female labour participate in this discourse. In The Gleaner, c. 1908, for example, although the woman is young and pretty, her hair is tied up in a messy bun, her face and neck are sunburnt, and her rough hand is clenched around the heavy bundle of hay. Contemporaries would have read these characteristics as signs of difference from the middle-class, white, feminine ideal represented in other McNicoll paintings (In the Shadow of the Tree, c. 1914, for example).

McNicoll’s labouring rural subjects were well received by critics in Canada, who compared her art favourably to that of her French peers. “Her work is characterized by simplicity of composition and breadth of treatment, allied with undoubted strength and an eye for the poetic in common objects,” said one reviewer of the 1909 exhibition submissions: “Her work is exceedingly promising, and seems to indicate that later on she may be able to do for the habitant types of French Canada something of what Millet did for the peasantry of France.” When The Apple Gatherer was exhibited in the Spring Exhibition of the Art Association of Montreal in 1911, critic William R. Watson described it as one of the “delightfully sunshiney pictures of which Miss McNicoll is now an almost perfect master.”

McNicoll returned to the subject of orchards on a number of occasions, including in The Orchard, n.d., and Apple Time, n.d. Natalie Luckyj proposes that these works may have been inspired by McNicoll’s time painting with British artist and teacher Algernon Talmage (1871–1939) in St. Ives—a teacher who encouraged his students to paint en plein air and held classes in a local orchard. The subject was also popular with Impressionist artists—French landscapist Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) tackled it, as did American Mary Cassatt (1844–1926). Cassatt’s mural for the Women’s Building of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair portrayed a group of women picking fruit as an allegory for modern woman, imbuing the subject with the feminist theme “Young Women Plucking the Fruits of Knowledge or Science.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements