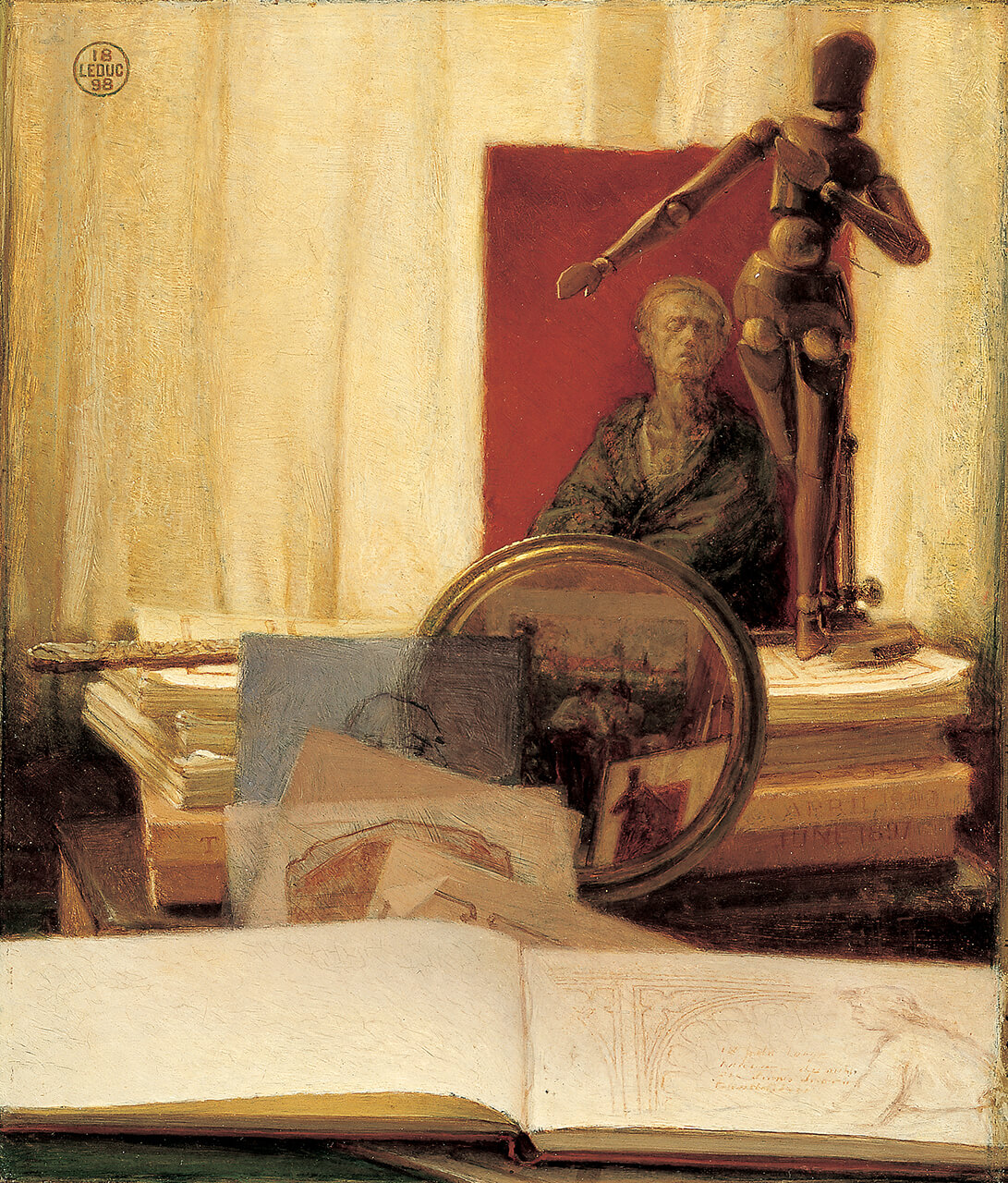

Still Life with Lay Figure 1898

Ozias Leduc, Still Life with Lay Figure (Nature morte dite “au mannequin”), 1898

Oil on cardboard, 28 x 24 cm

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

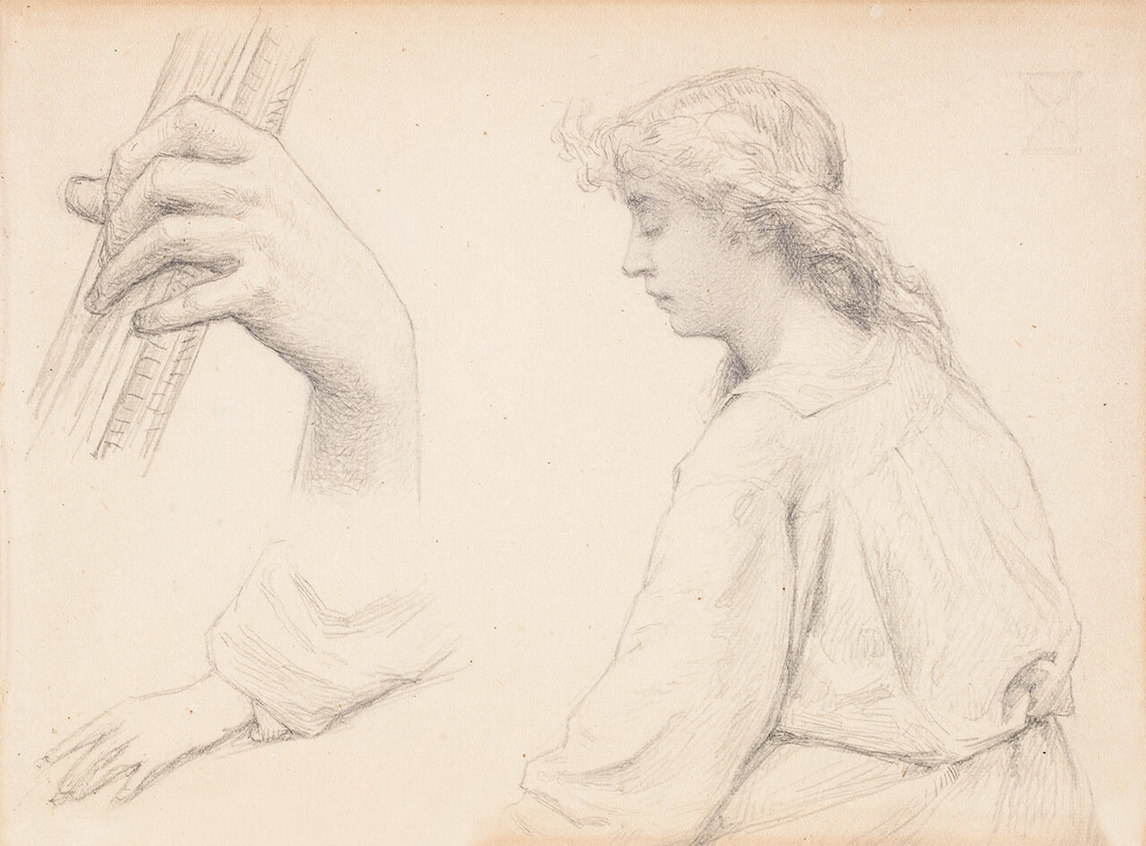

The end of a table is placed against a window with a white curtain; a rich pearly light filters its way through. Books, magazines, a letter opener, a sketchbook, a round mirror, and some drawings are piled on the table along with a mannequin and a bas-relief of an emaciated man wrapped in blue drapery and set against a red background. The work environment reveals a certain amount of chaos in the stacks of papers interleaved and piled on top of each other. The overlapping drawings, images within the image, some of which are opaque and others transparent, are preparatory studies for the decoration of the Saint-Hilaire church, including a page taken from a sketchbook.

The mirror in the centre, offering a microcosm of this creative space, reflects bits of the room’s decor, including some elements that do not appear in the picture itself. The articulated mannequin, which Leduc used to study poses when he was without a live model, is associated with the reflection of what seems to be a detail from a painting of two figures in prayer. The mannequin, with one arm held out to the side and the other folded against its chest, performs a gesture of deference. The iconographic motifs thus weave a network of forms and meanings whose message is elusive.

For Leduc, a still life is an occasion to reflect on the nature and significance of objects when they are combined. But more than that, it is a stage on which to consider space and the relations that are established between the objects in that space. In this regard, in order to perceive the gaps that separate or unify the contents of an image, their form and their texture, light must play an essential role.

This work is a manifesto of sorts, a statement of Leduc’s artistic intention and program. Around the edge of the picture, in the part hidden under the frame, Leduc has inscribed not only the place and date of the making of this work, but also his credo: that drawing, colour, and composition are his alpha and omega, the foundation of his art. The inscription reads as follows: OZIAS LEDUC PAINTED THIS PICTURE in FEBRUARY and MARCH 1898 at St HENRI de MONTREAL / DRAWING // COLOUR // COMPOSITION // THE // TRINITY // OF // THE PAINTER. In choosing a theological metaphor to describe the fundamentals of painting, Leduc asserts that the three components are at once distinct and united in a single art form. The other part of the inscription is equally valuable, in that it shows that Leduc spent part of the winter of 1898 in Montreal. No doubt the studio at Saint-Hilaire would have been cold, not a comfortable temperature for work. Since his return from France at the end of December 1897, he had been working on a concept for the decor of the Saint-Hilaire church. He was then staying with his cousin and future wife, Marie-Louise Lebrun Capello, at 1049 rue Saint-Jacques.

A fragment of a label still attached to the back of Still Life with Lay Figure indicates that the work was exhibited at the Spring 1898 Salon of the Art Association of Montreal, where it was valued at a modest forty dollars ($1,200 today). It is not known exactly when it became the property of the businessman Oscar Dufresne, who was only twenty-three at the time. However, on Dufresne’s death in 1936 the picture passed to his brother Marius. It was later acquired by the industrialist and philanthropist David M. Stewart along with other possessions of the Château Dufresne and in 1984 was donated to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements