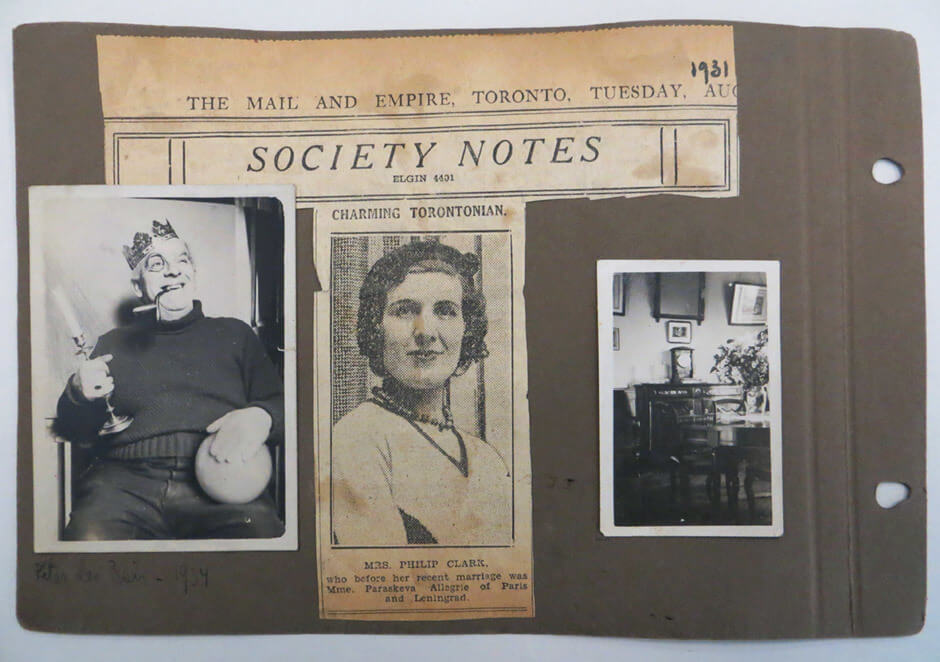

When Paraskeva Clark immigrated to Canada in 1931, she brought fresh eyes with which to observe the Canadian scene. With her European training and experience, she was soon identified as a Canadian modernist, and in the late 1930s and 1940s her socialist leanings equipped her to be a passionate spokesperson for socially engaged art. Her life and art reveal the challenges, frustrations, and successes of a Russian-born woman in a city whose dominant culture was British.

An Émigré Artist

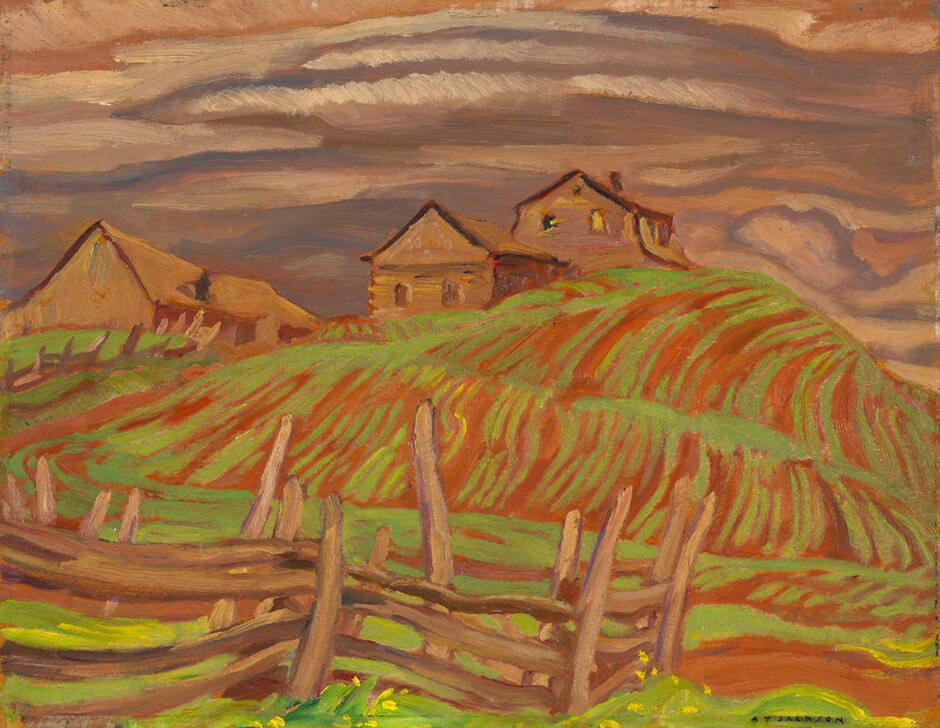

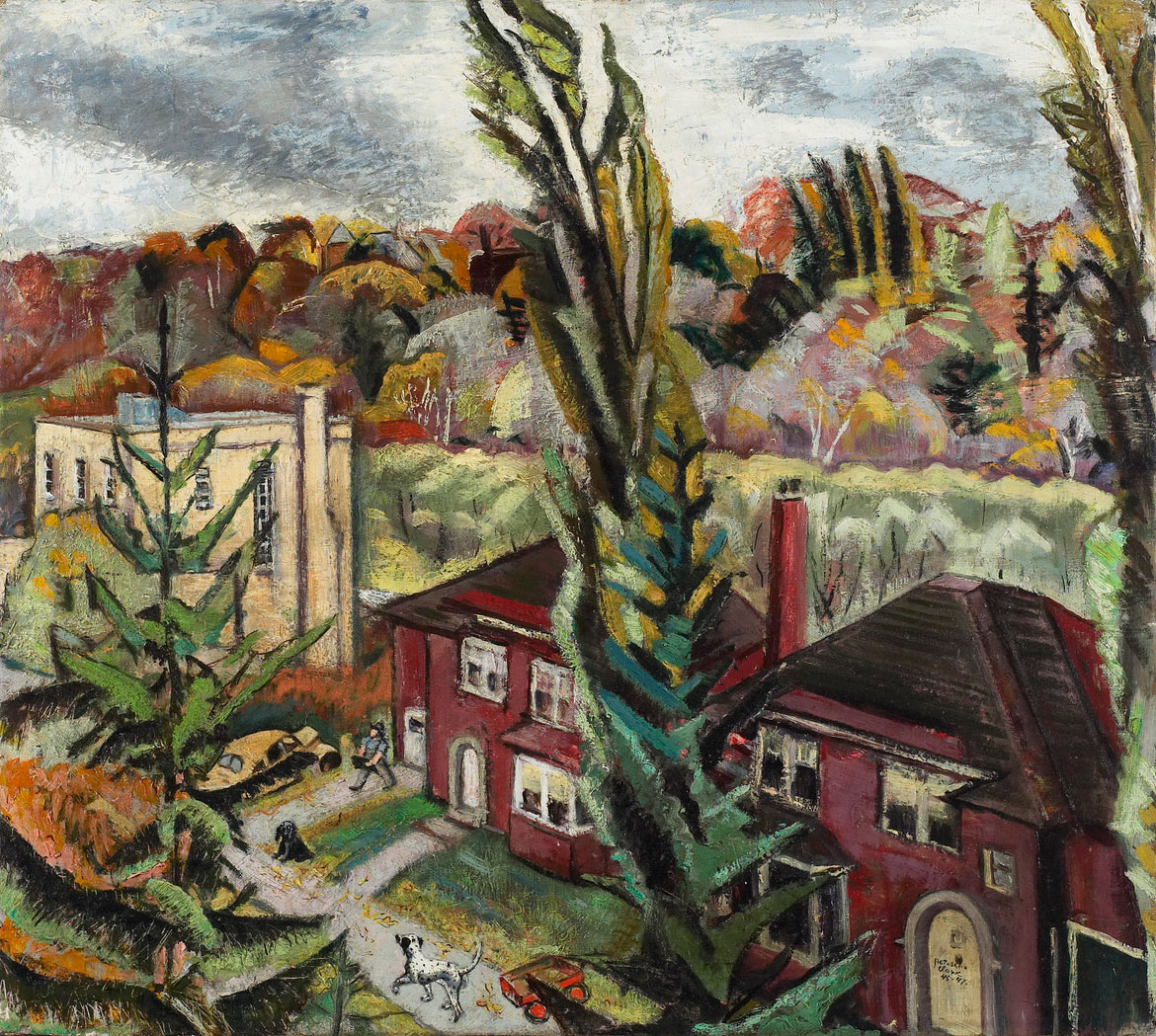

Once she moved to Canada, Clark lived a comfortable life, even during the Depression, and was quickly accepted into Toronto’s art circles. She had experience in adapting to shifting circumstances, and she recognized that Canada had made her a painter. Although she criticized Toronto artists for their fixation on landscape, she produced a large number of landscapes herself (including Wheat Field, 1936; In the Woods, 1939; and Canoe Lake Woods, 1952) because she knew that this genre sold well in Canada. She may have painted in some of the same locations as the Group of Seven (Georgian Bay, Algonquin Park, Quebec), but she was recognized for the fresh eye she brought to an overworked genre with her formalist approach and humanist concerns.

Despite the relative ease with which she entered the Canadian art world and settled in her adoptive home, Clark was an “exile” in many ways. Around the start of the Second World War, she confided to her close friend Douglas Duncan that she felt even more of a foreigner than ever, and once the Cold War began, she was much less vocal about her Communist sympathies. Nonetheless, she would not (or could not) assimilate completely into Toronto’s English-Canadian establishment, at whose centre (Rosedale) she lived, and often played up her “difference.” There were other Russian émigré artists in Toronto at that time, notably Yulia Biriukova (1897–1972), but Clark had little to do with her—a “White Russian.”

As Susan Rubin Suleiman points out, exile can be understood in a broader sense to designate every kind of estrangement or displacement—physical, geographical, and spiritual. Edward Said described exile as the unhealable rift forced between a human being and a native place, between the self and its true home. The essential sadness of this state, he observed, is insurmountable. Filmmaker Gail Singer suggested that Paraskeva Clark used defiance and anger to keep her sadness at bay—and to keep her young, outspoken self alive.

For the exile, daily life in the new environment happens against the memory of habits and activities in the old environment, so the past and the present occur “contrapuntally.” In Clark’s case, this duality is most evident in the two Memories of Leningrad series (Russian Bath and Mother and Child), to which she turned when strong emotions experienced in the moment triggered memories of similar feelings in the past. For the most part, her paintings were studies in form and realism. Clark claimed never to paint the sentimental, but at times she touched on it.

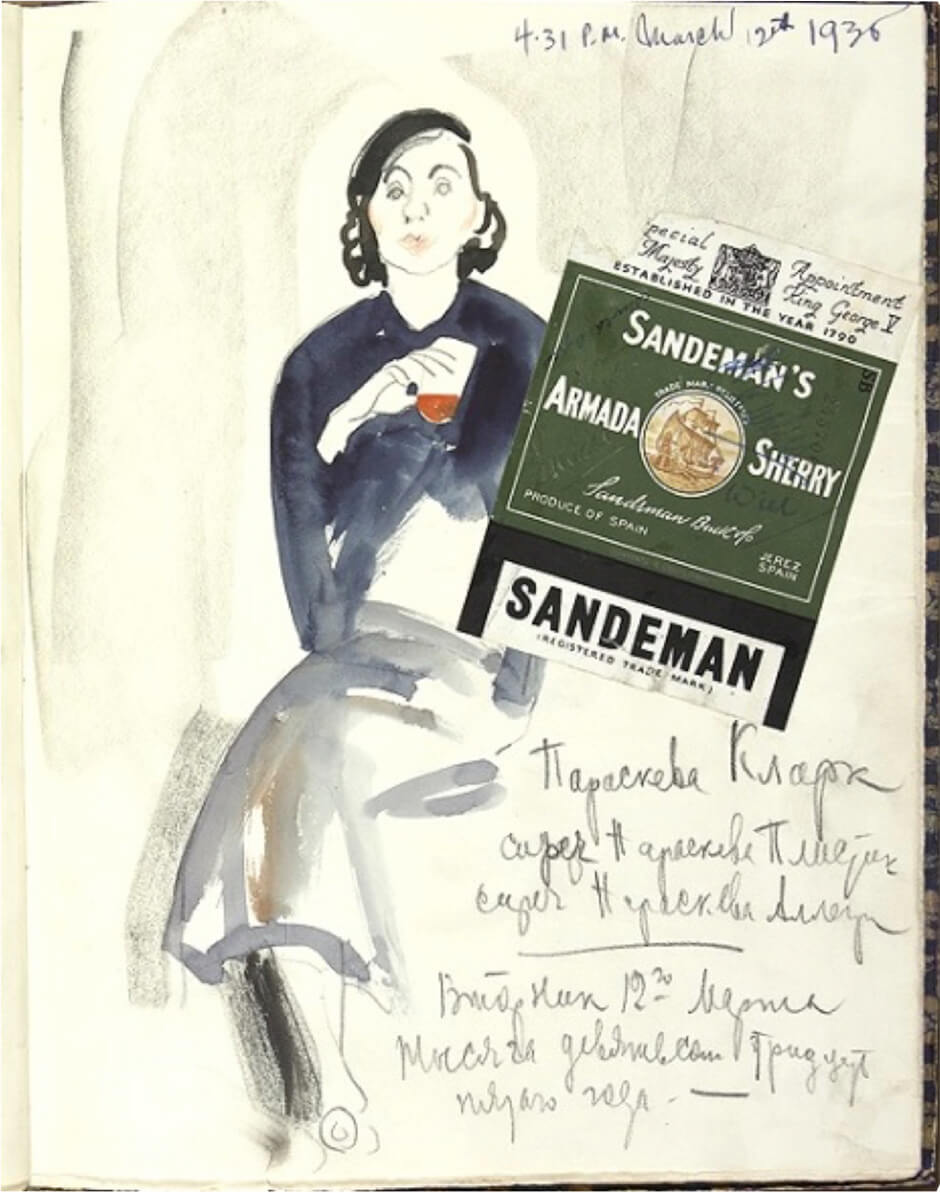

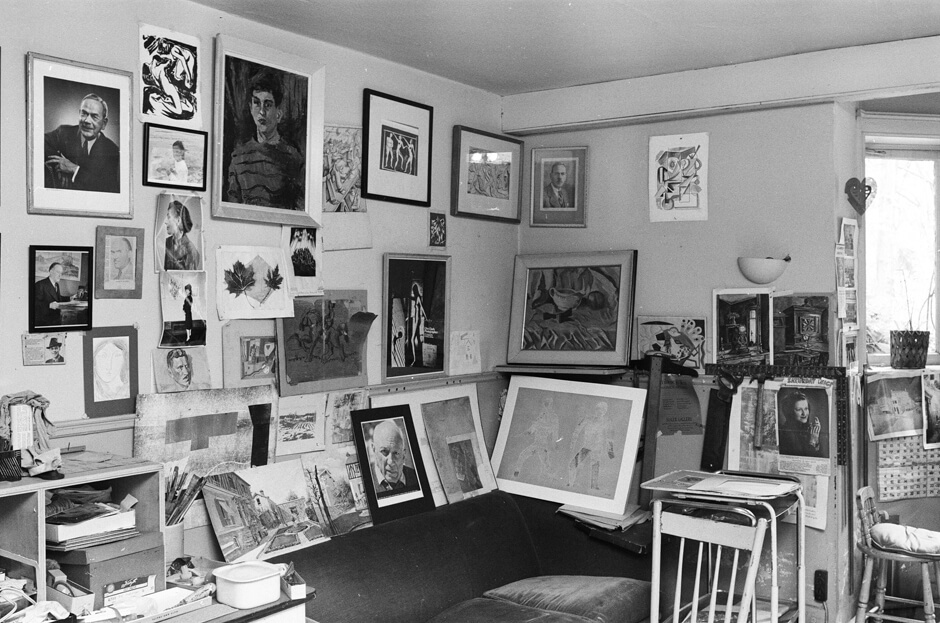

In the personal space of her studio, Clark surrounded herself not only with her own work and reproductions by other artists but also with mnemonic aids, photographs, and paraphernalia, some from her life in Russia. She never returned to Leningrad, and perhaps it would have been too difficult for her emotionally and logistically. She died in 1987, before the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Artist Panya Clark Espinal has sensitively captured the essence of her grandmother’s character in these words:

With one hand tied to her peasant and socialist roots and the other to her refined capacity for eloquence and expression among artists and intellectuals, Paraskeva occupied a threshold between two profound commitments. It seems she lived a long and laboured life, struggling to keep both faiths alive.

The Artist and Society

In the 1930s many artists developed a concern with social issues, which manifested itself in different ways. When Paraskeva arrived in Toronto in 1931, she became part of a new group of younger artists who wanted to broaden the scope of Canadian art. Art historian Anna Hudson has focused attention on the small, closely knit community of Toronto painters in the 1930s and 1940s (Charles Comfort [1900–1994], Bertram Brooker [1888–1955], Carl Schaefer [1903–1995], Clark) who injected a much-needed dose of humanity into contemporary art through depictions of the “cultivated landscape” and its people. They became members of the Canadian Group of Painters (CGP), formed in 1933.

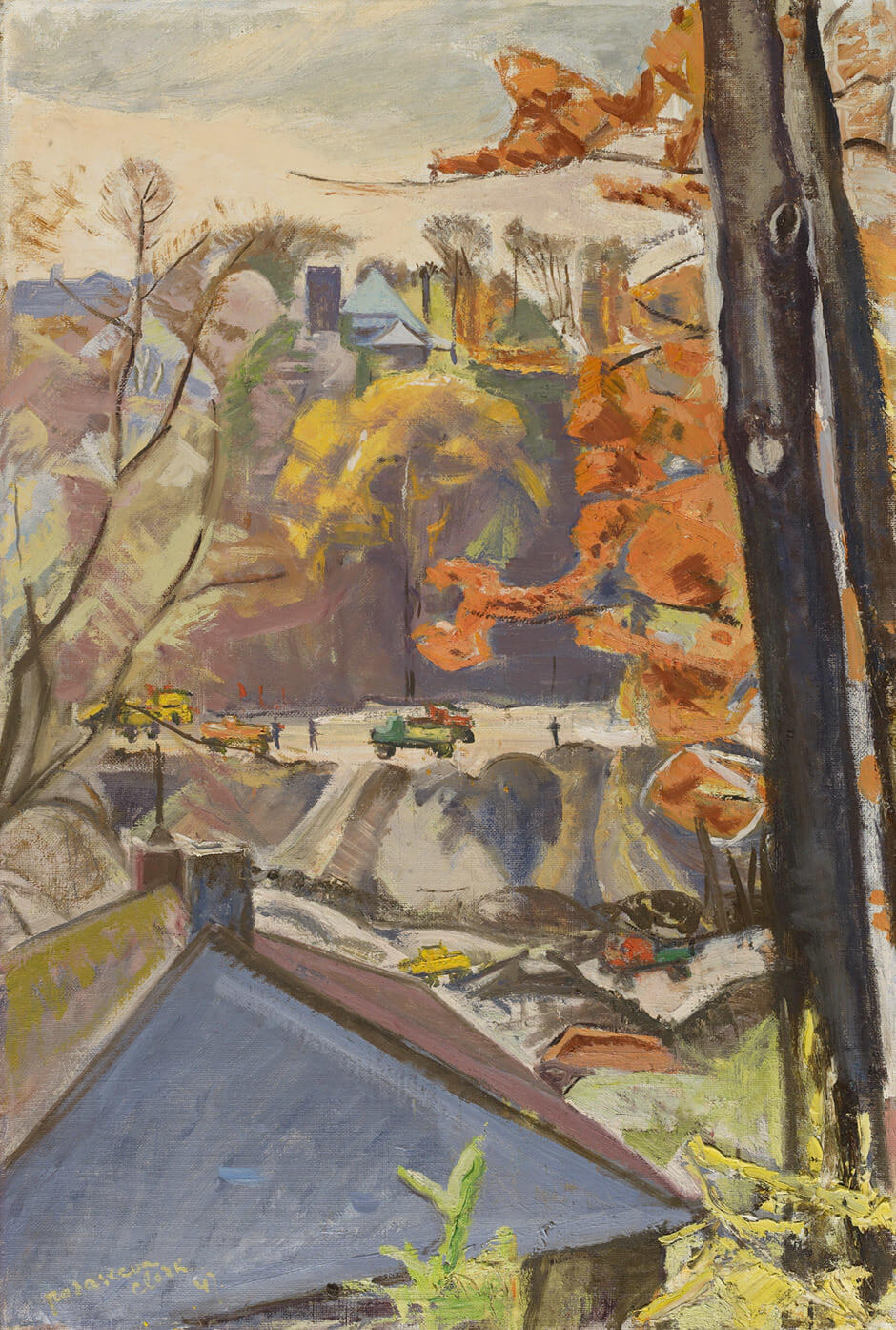

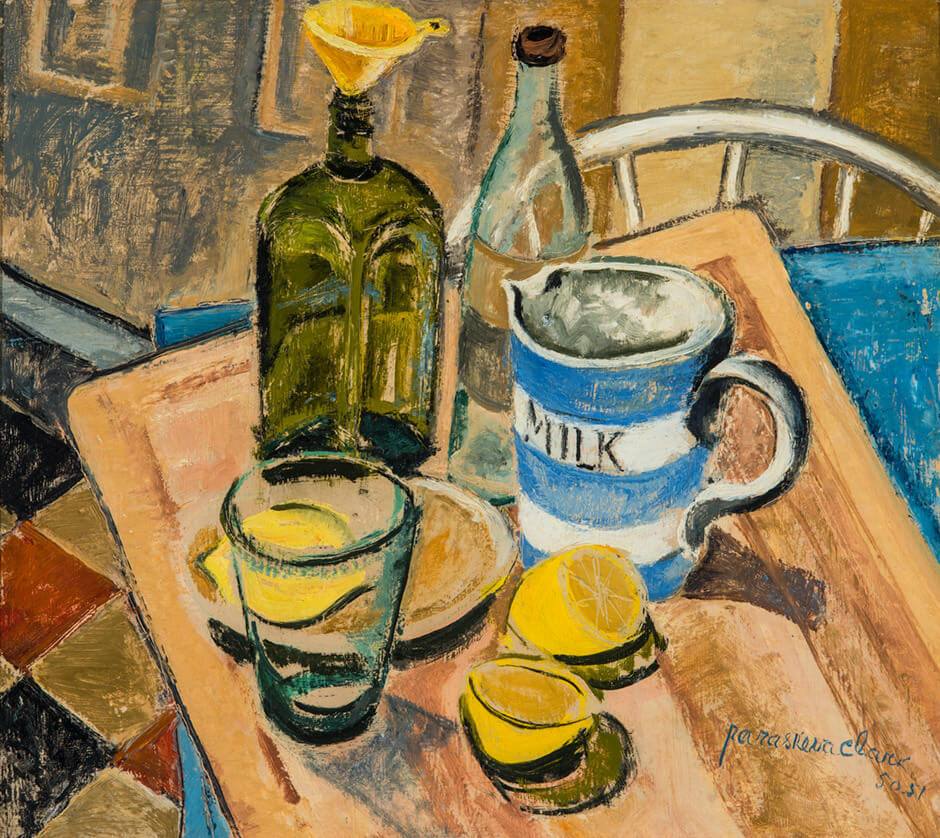

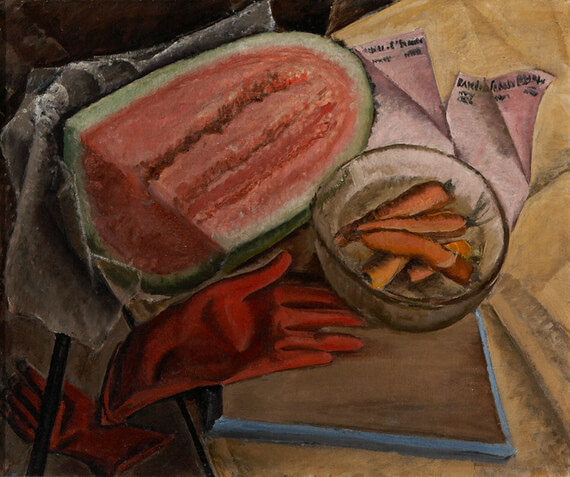

Clark would paint many views of the everyday world around her, including Snowfall, 1935, and Our Street in Autumn, 1945–47, along with inanimate arrangements such as Still Life, 1950–51. She believed that artists had a “finer understanding and perception of the realities of life, and the ability to arouse emotions through the creation of forms and images,” and encouraged Canadian artists to “paint the raw sappy life that moves … about you, paint portraits of your own Canadian leaders, depict happy dreams for your Canadian souls.”

In Canada during the Depression, difficult societal conditions gave rise to a social democratic movement, culminating in 1932 with the founding of the League for Social Reconstruction (LSR) and the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF). Social commitment became an issue for many artists with leftist sympathies. As Esther Trépanier and others have pointed out, 1936 was a significant year for the issue of art and politics in Canada. “Art and Society” was the theme of Bertram Brooker’s introduction to the 1936 Yearbook of the Arts in Canada, which included Clark’s Still Life, 1935, and gave rise to a debate in left-leaning journals of the day.

Clark herself became engaged in social activism. When the Spanish Civil War erupted in the summer of 1936, many artists (including Clark) supported the Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy set up by Dr. Norman Bethune. Clark met Bethune during the summer of 1936 when he was in Toronto raising funds to travel to Spain to provide medical aid for the Republican side. He had visited Leningrad in 1935 and, subsequently, joined the Communist Party of Canada. He turned Clark’s attention to politics, and his letters from Spain (lost or destroyed) surely reinforced their discussions about art and society.

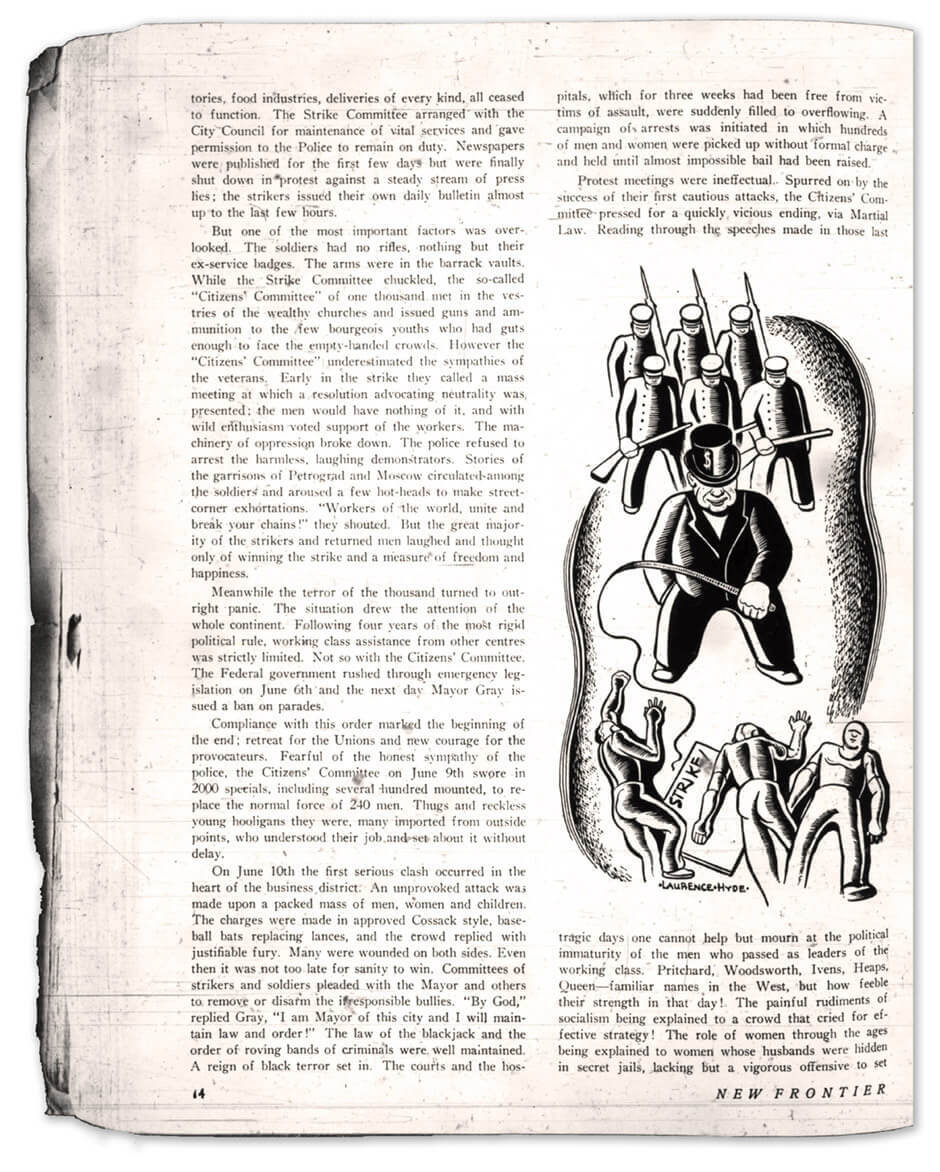

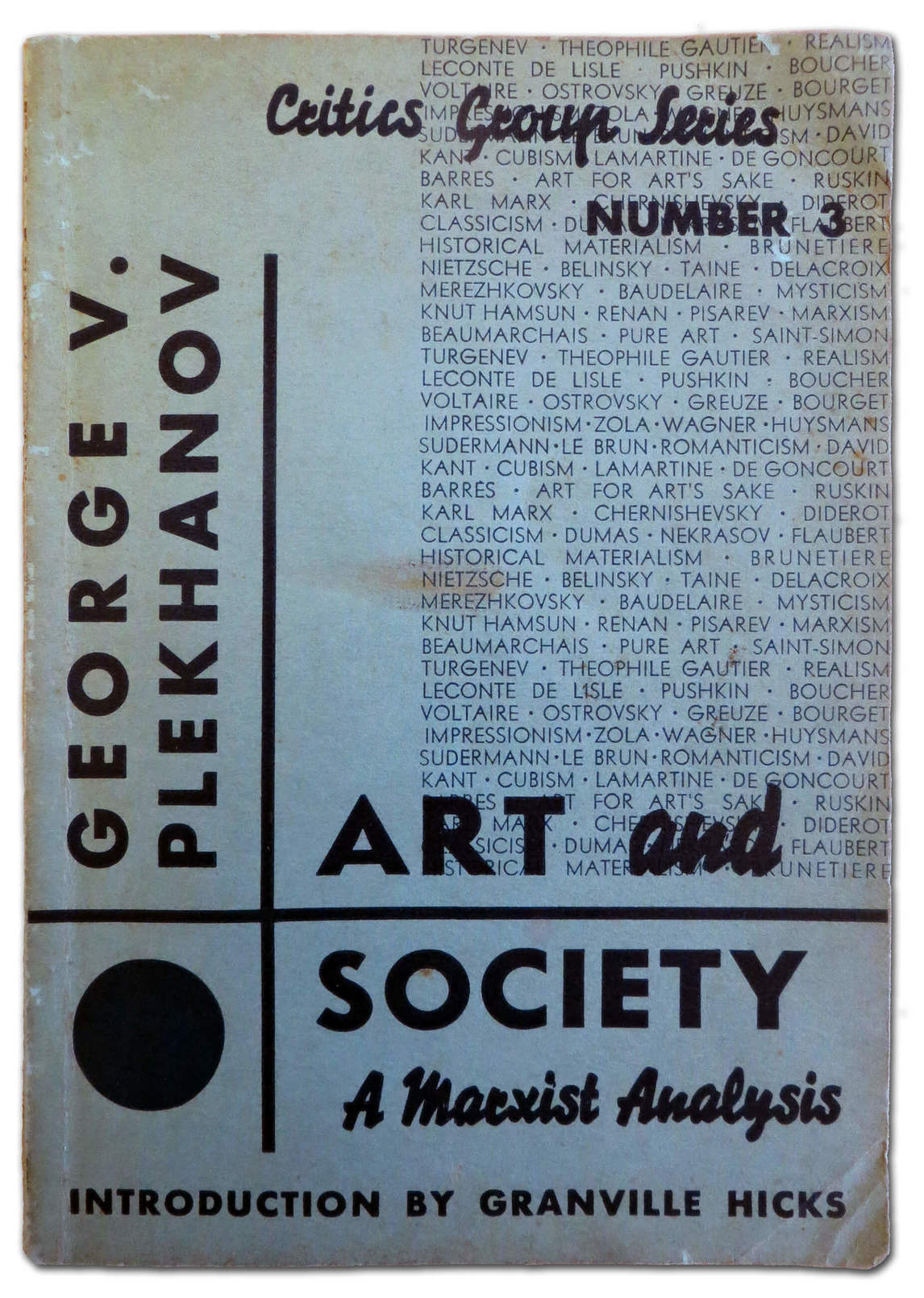

Perhaps on Bethune’s suggestion, Clark also acquired a copy of Art and Society by Georgi Plekhanov (1856–1918), published in English in 1936. She seems to have read it during the winter of 1936–37, because ideas from this Marxist essay are echoed in the article she wrote, with the help of Graham McInnes, for the April 1937 edition of the leftist journal New Frontier. In “Come Out from Behind the Pre-Cambrian Shield,” Clark responded to Plekhanov’s statement, “All human activities must serve mankind if they are not to remain useless and idle occupations.” As she wrote: “I cannot imagine a more inspiring role than that which the artist is asked to play for the defence and advancement of civilisation.”

In addition to the articles she wrote and her involvement with fundraising efforts to support the Spanish Republican cause, Clark’s activism briefly extended to her art. This commitment set her apart, as few Canadian artists attempted social or political issues in their work in the 1930s. The images with political content that Clark exhibited, especially in 1937–38, address Plekhanov’s point that “the function of art is the reproduction of life and its pronouncement of judgment on the phenomena of life.” After exhibiting Petroushka in 1937, she showed three watercolours in the annual exhibition of the Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour in 1938, including Evening Promenade, Mao Tse Tung, and Mass Meeting. Graham McInnes commented that Mao and Mass Meeting smacked of propaganda, Mao with its associative and literary emblems and Mass Meeting for the artist’s use of photographic sources, rather than relying solely on the plastic conventions of painting. He associated her use of avant-garde techniques with propaganda.

In the 1940s, she painted several oils—Pavlichenko and Her Comrades at the Toronto City Hall in 1943; In a Toronto Streetcar, 1944—which celebrated the end of the siege of Leningrad; and a scene of a blind woman being guided on a streetcar. There was also the work, such as Parachute Riggers, 1947, that she did for the Canadian War Records in the years 1945–47. In her desire to help Russia during the war, portrayed in Self-Portrait with Concert Program, 1942, Clark held a sale of her work in December 1942 at the Picture Loan Society. She truly believed in the cause of the Russian people, and she raised around $500 to donate to the Canadian Aid to Russia Fund.

By the early 1940s, Clark was committed to commenting on the social issues of the day through figure compositions. Once the war was over, however, other forms of artistic expression soon eclipsed social realism; it bore too close a resemblance to Soviet Socialist Realism. Thereafter, various forms of abstraction became the dominant art language of the West.

Clark as a Woman Artist

You know, it’s not the very best, but the talent is there. And a lot of women are very good painters. And because they are not as men, I mean, the world is just simply polluted with bad man painters who sell. And public doesn’t trust the women, eh? Think they are no good. They are good only for cooking.

—Paraskeva Clark

Within the last decade, feminist strategies have been helpful in considering Clark’s position as a professional Canadian woman artist. Natalie Luckyj examined Clark’s refashioning of self through her art, the place where she was able to bring together her conflicting identities: public and private, political and personal. Kristina Huneault and Janice Anderson have edited a collection of essays that explores the historical relation between women, art, and professionalism.

Paraskeva Plistik was born into the Russian working class—and she called herself a “peasant” with some pride. Marriage to Oreste Allegri Jr. in 1922 gave her social mobility, entrée into a creative element in society, and some financial security. She gave birth to a son in 1923. Given her background, she would not have questioned entering into marriage and motherhood in her early to mid-twenties.

Widowed and with a young child, Clark married a second time in 1931, to Philip Clark. Again, marriage gave her the opportunity to reinvent herself and work at becoming an artist in Canada; yet, marriage could be confining. For Clark, the roles of wife, mother, and housekeeper came first, limiting the amount of time and energy she could dedicate to her art. She complained about these demands frequently in later years, when she enjoyed little respite from her domestic duties. They became particularly onerous as she took care of her older son, Ben, who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and remained dependent.

Very few of the women artists of Clark’s generation had children. Pegi Nicol MacLeod (1904–1949) complained of losing the focus required for painting after her child was born, while Rody Kenny Courtice (1891–1973) admitted that it was possible for a woman to combine the roles of wife, mother, and artist successfully—if she fought hard enough. Some, like Kathleen Daly Pepper (1898–1994) and Bobs Cogill Haworth (1900–1988), married other artists and remained childless. Yvonne McKague Housser (1897–1996), whose marriage to Fred Housser ended after one year when he died in 1936, supported herself by teaching. Isabel McLaughlin (1903–2002) did not marry and was of independent means. Clark could not have made a living from the sale of her art alone.

Clark believed that women could not be great painters. Gail Singer, director of the documentary film Portrait of the Artist as an Old Lady, who knew her subject well, observed that Clark had a conventional view of herself—as being “only a woman” and therefore “limited” in what she could accomplish as an artist. This attitude reflected the status of women during her lifetime, which may also account for her insecurities about her art. Graham McInnes, one of her staunch supporters, described her work as combining two qualities “unusual for a woman painter”—“extreme sensitiveness and wiry strength.”

Clark thought it unfair that women had been made to be mothers, “their heart always taken by anxiety or something, while in painting you have to close the key on the door from everything.” She was frustrated at not being able to give sustained periods of time to her art, thereby impeding her progress and limiting her output. She repeatedly spoke of painting as time “stolen from housework.”

Although Clark’s subject matter reflects the restrictions she faced in her daily life, she worked imaginatively within the narrow parameters open to her. She experimented widely, painting in a variety of different styles at the same time, particularly in later years. Given the many demands on her, however, she often didn’t have the uninterrupted time or the personal space to fully develop an idea or an approach. Nor did she have the opportunity for regular travel further afield than Toronto or Montreal to see a broader range of contemporary art. During difficult family periods, such as Ben’s illness, she stopped painting. But she continued to exhibit what work she had.

Paraskeva Clark was a feminist avant la lettre, as were many women of her generation. Russell Harper commented parenthetically in his Painting in Canada: A History (1966) on the “great number of women painters in Canada, both in Montreal and in Toronto,” as “one remarkable phenomenon of the times [the 1930s].” He mentions Clark (along with Kathleen Daly) in passing, as artists “spiritually akin” to but who enlarged the range of their subject matter beyond that of the Group of Seven. In the past several decades, Canadian curators and art historians have been engaged in recovering a large number of artists—many of them women—whose work fell outside this nationalist framework and was subsequently overlooked.

Critical Reception

Clark’s artistic legacy rests solidly on her socially engaged work and modernist approach to art in the 1930s and 1940s. As early as 1937, she was recognized as a modern painter who had made a contribution to Canadian landscape. Initially, critics looked for qualities in her work that they considered characteristic of her Russian heritage and French experience, distinguishing it within Canada’s predominantly Anglo-Saxon culture. Graham McInnes wrote that Clark had brought “her native sensibility and her talent for conceiving plastic relationships” to the Canadian scene; in 1950, he mentioned her “Russian sense of explosive colour and her French love of classical form,” with results that were “joyous yet restrained, intense yet controlled.” Pegi Nicol wrote of Clark’s art as embodying “troika bell mirth and gloom.” Andrew Bell found her Canadianness “remarkable” in 1949, given that she had been in Canada a relatively short time. In 1952, one reviewer deemed her the leading woman painter in Canada since the death of Emily Carr.

Since the 1960s, the writing of Canadian art history within a nationalist framework has marginalized artists who did not fit the mould, such as women or members of First Nations. Clark’s reclamation by the National Gallery exhibition Canadian Painting in the Thirties (1975), the Dalhousie Art Gallery’s Paraskeva Clark: Paintings and Drawings (1982), and the National Film Board of Canada’s Portrait of the Artist as an Old Lady (1982) continues in the present through feminist readings of her work. The growing interest in Canadian women artists through the Canadian Women Artists History Initiative, exhibitions such as The Artist Herself (Kingston and Hamilton, 2015–16) and A Window on Paraskeva Clark (Ottawa, 2016) are keeping Clark’s legacy alive.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements