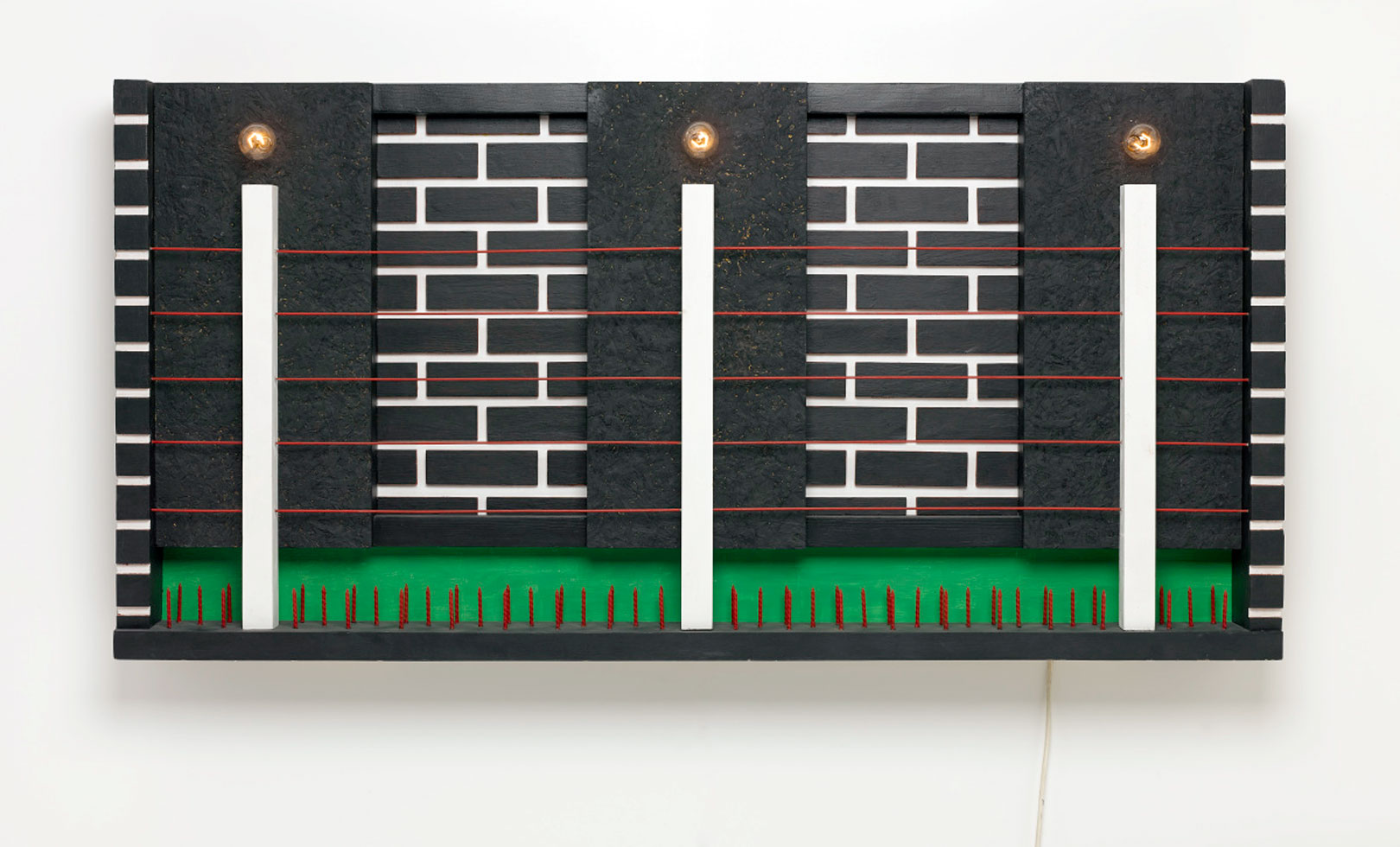

Composite 14 1996–97

Sorel Etrog, Composite 14, 1996–97

Wood and plywood, particle board, metal rod and screws, incandescent lamps and electrical fixtures, acrylic paint, 150 x 12 x 189.2 cm

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Sorel Etrog’s final burst of creativity, a series that he called Composites, returned to his very first body of work, the flat yet geometrically rich Painted Constructions of the 1950s. Like those early pieces, Composite 14 and its related works are meant to hang on the wall. He became inspired while visiting his cousin Sylvia Federman and her husband, Burton, in Florida in 1996: “Burt had a garage with more tools than any sculptor I knew. I found myself in his garage making my first wood constructions since the 1950s.” On returning to Toronto he began collecting not only scraps of wood but also such ready-made objects as plastic milk crates, rubber doormats, and light bulbs, which he combined to create his colourful geometric collages.

Composite 14 is a flat rectangular assemblage with several relief elements layered on its surface. Its composition is balanced and geometric, with a primarily horizontal orientation. At the bottom of the piece, and stretched across the work’s surface, is a band of green paint placed under an intermittent black and white brick pattern and five red metal lines that transect the whole work, anchored in place by three white vertical posts topped with glowing light bulbs. Two rows of short red nails are hammered into the bottom frame of the piece and stand upright in front of the green band.

In 1996, Etrog returned to his country of birth, Romania, for the first time in forty-six years. Although he did not go to his hometown of Iasi, a visit to a prisoner-of-war camp brought back painful memories. The Composites draw on this experience as well as his traumatic childhood growing up as a Jew in anti-Semitic Romania during the Second World War and the later Soviet occupation. The vertical and horizontal forms in Composite 14 bring to mind electric fences, barbed wire, walls, and other physical barriers that surrounded the concentration camps, those spaces of death and torture used by the Nazis to eradicate the Jewish population of Europe. The thin red lines stretched between white poles appear like a fence, and the working light bulbs suggest searchlights. The short red nails at the bottom add to the sense of impassability, just as the layered bricks present an enclosed space with no openings. Other works in the series suggest prison cells and deportation trains, even the gas chambers themselves.

The Composites were first exhibited at Christopher Cutts Gallery in Toronto in 2000. In the exhibition catalogue Etrog’s friend the art critic Gary Michael Dault interprets the pieces in stylistic terms, arguing that they present a retrospective summary of the artist’s career:

Here, for example, is a checklist of Etrogisms—echoes and remodulations of the artist’s working vocabulary—present in the composites: hinges—an evolution of the link, so prevalent in classic Etrog sculpture of the 60s and 70s…. Deep glossy colour (the kind of colour borne by the Composites acknowledges the shiny, baked and buffed automobile-enamel of, for example, the Screws and Bolts sculptures of the early 70s). Severe geometric planes, shaped and acknowledged for their own formal power and powerfully juxtaposed— as in the new, radically simplified steel wall sculptures of the early 80s.

This formalist interpretation fails to take into account the subject matter of the Composites; they were directly related to both recent and long-past events in the artist’s personal life. The art historian Joyce Zemans, also a friend of Etrog’s, interpreted the works in light of his biography. To her, their composition and formal arrangement are not abstract, nor are they “the random associations of the Dadaists. The objects evoke the violence that has, for the most part, lain hidden below the surface in Etrog’s work…. The composites are, in fact, layered and coded with meaning.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements