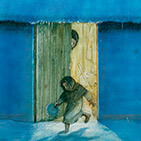

Hailstorm in Alberta 1961

William Kurelek, Hailstorm in Alberta, 1961

Oil on composition board, 69.3 x 48.2 cm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

In 1961 the volunteer Women’s Committee of the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario) invited Alfred H. Barr Jr. to select a painting by a contemporary Canadian artist for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) permanent collection. The expectation was that Barr, MoMA’s director of collections and an internationally recognized authority on Cubism and Post-Impressionism, would choose a work by one of Toronto’s growing number of modern abstract artists, such as Harold Town (1924–1990), Gordon Rayner (1935–2010), or Kurelek’s former Ontario College of Art classmate Graham Coughtry (1931–1999). Instead, Barr selected Kurelek’s Hailstorm in Alberta, and Kurelek provided MoMA with this description of his work: “A personal memory drawn from my father’s account. I was a child hiding in the house with my mother when that particular hailstorm came and can just remember her putting pillows in all the windows, and admiring the sizes of the stones outside after the sun came out.” Unbeknownst to Kurelek, his dealer, Avrom Isaacs, had submitted the painting for consideration. MoMA’s acquisition buoyed Kurelek’s self-confidence, which had already begun to improve following the success of his first solo exhibition at Isaacs Gallery less than a year earlier.

The painting is also a notable early example of Kurelek’s ability to create imagery resistant to reductive interpretations of his work as representing quaint, humorous childhood memories of Western Canada. Whether in representations of flood or fire, blizzard or drought, the ambivalence of the natural world toward the affairs and values of humans would become a crucial theme in Kurelek’s later work. Although he was inspired by environmental beauty, he often emphasized its impersonality so that his work could not be read as a celebration of pantheism. Kurelek’s Roman Catholic God was creator of the natural world, not a manifestation of it.

In this regard Hailstorm in Alberta follows in the footsteps of Northern Renaissance artists for whom local settings underlined God’s immanence in the lived world. It shows particular debt to Pieter Bruegel (1525–1569), whose work Kurelek had seen during his 1952 travels to art museums in Europe. In what Kurelek described as “the naïve, earthy, unclassical, almost brutal aspect” of his painting style, and the sprawling central figure, vulnerable and misshapen on the miserable black earth, we recognize at once Bruegel’s harsh and sympathetic view of flawed humanity.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements