Alfred Pellan spent a significant part of his early career in Paris, and he was influenced by European modernism—an artistic movement whose followers rebelled against conservative, academic traditions. Pellan fully embraced experimental approaches to artmaking, although this decision was initially met with resistance in his country of origin, where conventional ideas still dominated the Quebec art scene. His oeuvre reflects a blend of various elements: Pellan managed to incorporate his personal beliefs, his formal training, and his interpretation of Quebecois culture into his own synthesis of European modern art.

Parisian Influences

It can be a challenge to identify specific stylistic periods in Pellan’s art, as his oeuvre did not evolve in a strict linear fashion. Art historians have claimed that he is “impossible to catalogue” and “unclassifiable.” Still, one thing is clear: there is a clear distinction between everything Pellan produced before he travelled to Paris, where he lived from 1926 to 1940, and his subsequent work—that period changed his art forever. Although his preference for dominant colours and powerful, expressive brushstrokes is evident in early compositions such as Le port de Québec (Port of Quebec), 1922, those works are rooted in his classical training and reflect the academic tradition taught at the École des beaux-arts in Quebec. Compared with his paintings of the early 1920s, his Parisian work is notable for the ways in which it showcases his embrace of European modernism.

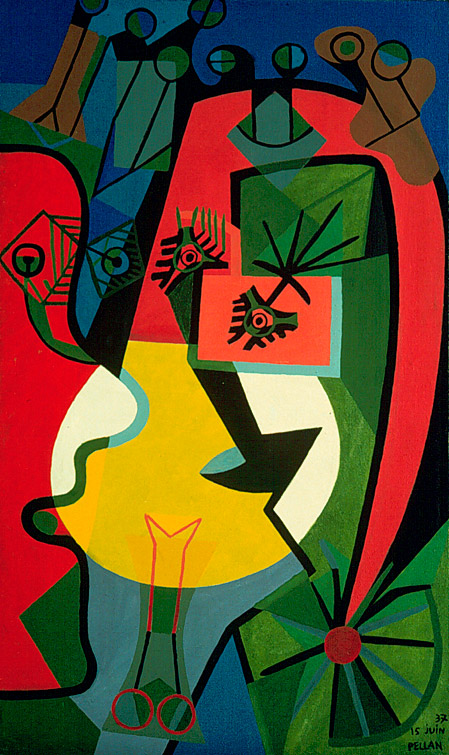

Pellan recognized the impact of his fellow artists in Europe. Works such as Bouche rieuse (Laughing Mouth), 1935, Désir au clair de la lune (Desire in the Light of the Moon), 1937, Vénus et le taureau (Venus and the Bull), c.1938, and La spirale (The Spiral), 1939, allude to the schematic sketches of artists Joan Miró (1893–1983) and Paul Klee (1879–1940). In Pellan’s eyes, Klee was “a painter par excellence, one for whom colour, drawing, composition come together to build a whole.” He also admired Max Ernst (1891–1976), whom he described as “a great pioneer.”

Pellan was also greatly influenced by Fernand Léger (1881–1955), whom he met around 1935 and would refer to as “perhaps the greatest painter of our time.” Pellan’s painting Magie de la chaussure (Magic of Shoes), 1947—which was based on an “exquisite corpse,” according to art historian Jean-René Ostiguy—recalls the mechanical and geometric forms that Léger used throughout his career to represent humans navigating the world. Similar themes would appear in later works as well, such as Les mécaniciennes (The Mechanics), 1958.

Pellan was also drawn to movements such as Fauvism, which he admired for the way its proponents used intense colour, as well as Cubism, Surrealism, and abstraction. In a 1960 interview, the artist explained that he “attempted to assimilate all the schools, all the techniques.” Pellan did not consider himself a purely abstract, Cubist, or Surrealist artist. He never wanted to become a “painter enlisted under any label or banner”; rather, he viewed all these styles as potential modes that could help him achieve his goals. During a conversation with the poet and writer André Breton (1896–1966), he expressed his desire to synthesize Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, and Surrealism into a coherent whole.

Pellan often combined elements he borrowed from various artists, with the aim of developing them in his work. This led to unique interpretations of his source material. In paintings like Nature morte aux deux couteaux (Still Life with Two Knives), 1942, and Le couteau à pain ondulé (The Serrated Bread Knife), 1942, for instance, he presents still lifes with experimental compositions. While Pellan was undoubtedly influenced by European art, he transformed his inspirations into something personal and specifically Pellanian through his own research and unique perspective. As one critic later claimed, Pellan passed “from one world to another, only to reject them all and to invent a new one.”

Experiments with Surrealism and Cubism

In 1942, Surrealist writer André Breton (1896–1966) declared, “All the inner lights shine for my friend Pellan.” Among the movements Pellan explored through his art, Surrealism stands out. “I have always been in love with it,” declared the artist in 1967, “and I still am, and I think I will always be Surrealist, because I think that Surrealism is great poetry.” Even so, he was never an official member of the group; although he did attend some meetings in cafés, he “witnessed it all from outside, without taking part in it.”

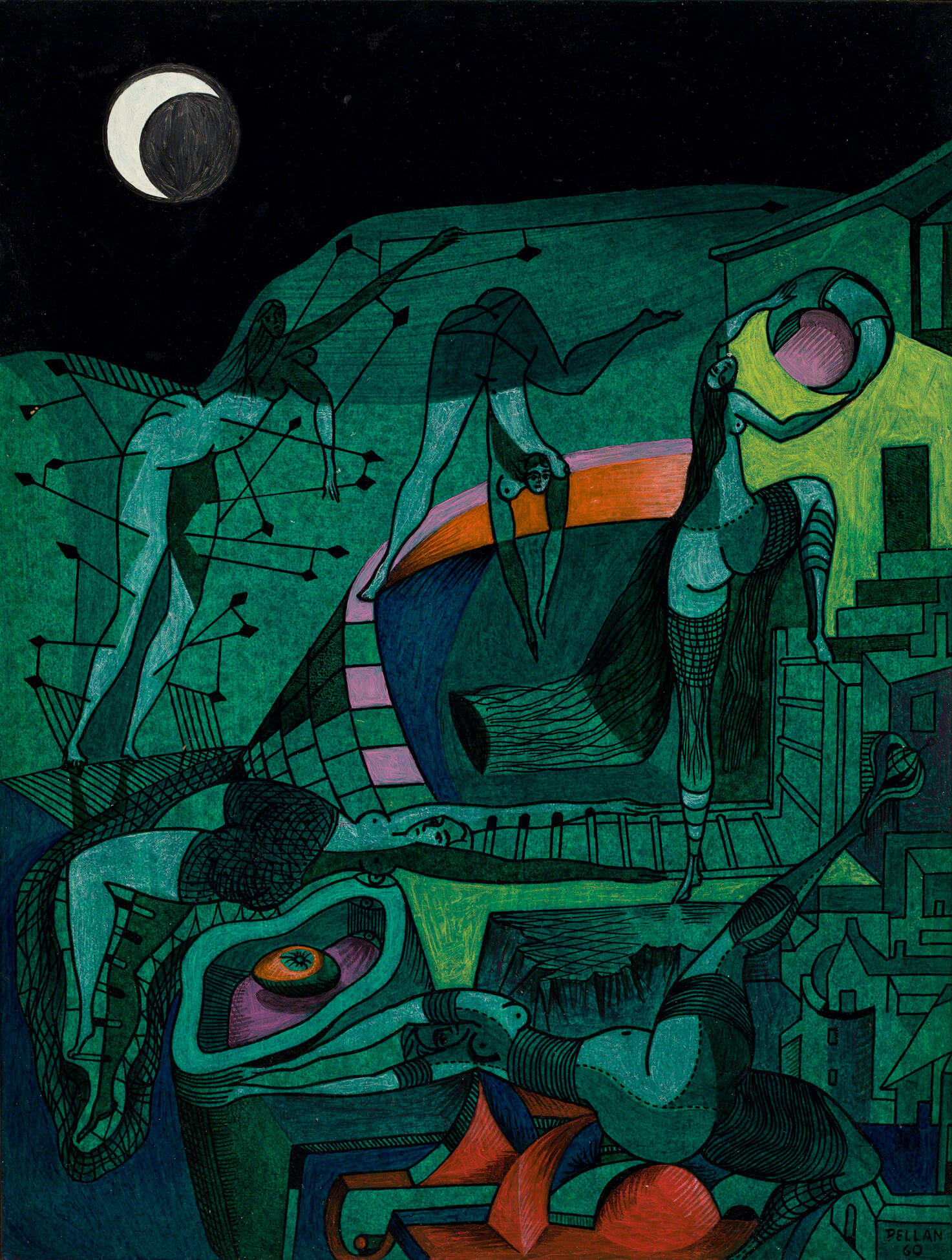

Pellan frequently employed Surrealist subject matter and imagery, often referencing the mysteries of the unconscious and depicting dreamlike visions, as can be seen in works such as Calme obscur (Dark Calm), 1944–47, and Croissant de lune (Crescent Moon), 1960. He also adopted some techniques commonly used by members of the group: he collaborated with his students to create “exquisite corpses” (a phrase that describes collectively assembling an arrangement of words or images); he juxtaposed incongruous objects in his compositions; and he experimented with automatism, or art created without conscious thought. He occasionally linked disparate images and forms to create unseemly combinations, or disrupted and broke up pictorial space to achieve work that could feel ambiguous, even contradictory. Pellan also presented biomorphic shapes and hybrid creatures, such as the suggestions of flora and fauna in paintings like Floraison (Blossoming), c.1950, and Les Carnivores (The Carnivores), 1966.

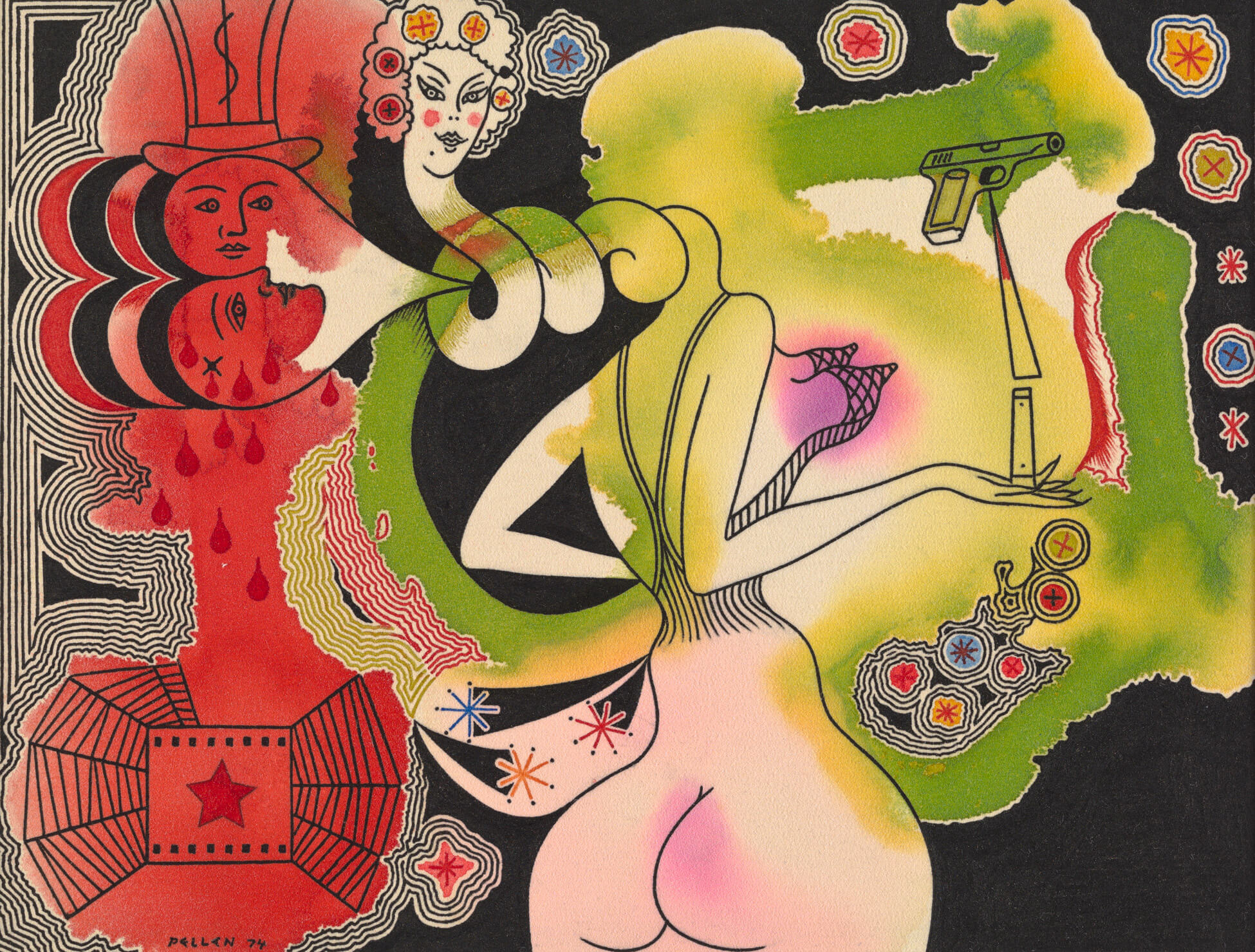

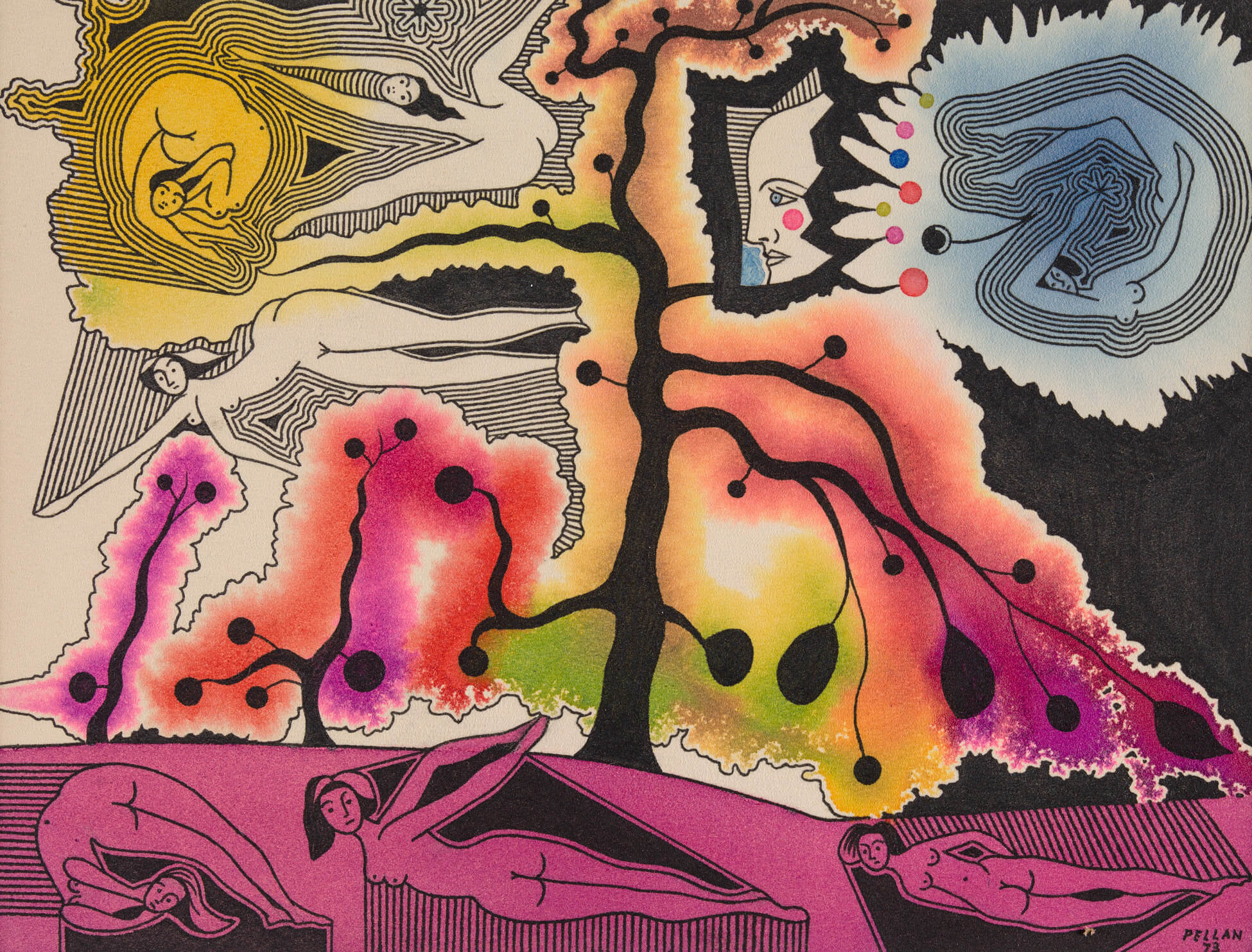

The artist brought a unique flair to his take on Surrealism. For instance, aiming to divest the movement of any “morbid” tendencies, he used vivid colour in works including L’amour fou (Hommage à André Breton) (Mad Love [Hommage to André Breton]), 1954, Hollywood, 1974, and Mutons…, 1974. In contrast to the famous Surrealist painter Salvador Dalí’s (1904–1989) sombre tones and clear contrasts created by light and shadow, Pellan’s colours seem to vibrate, creating an energy that breaks through the lines that try to keep them in check.

Surrealism had an important impact on French Canadian art and culture: in 1943, painter Fernand Leduc (1916–2014) declared that only Surrealism contained “a sufficient reserve of collective power to rally all generous energies and direct them towards the complete fulfillment of life.” According to art historian Natalie Luckyj, French Canadian artists remained remote and isolated compared with their European counterparts. However, Pellan’s ongoing exploration of Surrealist techniques and vocabulary suggests he was more actively engaged with the movement. Indeed, it was thanks to Pellan that Surrealism spread in Quebec: the “spirit of liberty and poetic visual language” in his work helped introduce characteristics of the movement to the region. More importantly, Pellan shared his adapted version of Surrealism with a younger generation of artists, including Mimi Parent (1924–2005) and her husband, Jean Benoît (1922–2010), who absorbed his influence.

Although Pellan considered his Cubist work of the 1930s and early 1940s to be merely a step toward his Surrealist explorations, he alternated between the two styles and frequently combined them, especially throughout the 1940s. While his composite images are Surrealist, the imagery of two fused heads attached to a single neck, which appears in several paintings, including Conciliabule (Secret Conversation), c.1945, derives from Pablo Picasso’s (1881–1973) Cubist heads, which incorporate frontal and profile views.

Moreover, Pellan’s Hommes-rugby (Footballers/Rugby Players), c.1935, and Sous-terre (Underground), 1938, are reminiscent of Picasso’s abstract Surrealism, as they seem to pulsate with “the same energetic curves and incorporat[e] the same areas of dot or striped pattern.” This integration of Cubist elements had been noted since the late 1930s, when art critics described Pellan as a “disciple of Picasso,” and even as the “Quebecois Picasso.” While they recognized the influence of the Spanish painter, these assessments also highlighted Pellan’s personal interpretation.

Although Pellan had been aware of Picasso’s work before his Parisian sojourn—his personal library included a book on the French painter by Maurice Raynal, a French art critic and ardent supporter of Cubism—it was only when he visited Picasso’s retrospective at the Georges Petit Gallery in Paris in 1937 that the artist fully realized the potential of shortened perspectives and formal decomposition.

Pellan and Picasso also met. “He simply knocked on my door,” said Picasso, “presented himself, and we talked about painting. I’ve listened to him with great interest.… Pellan asked to see my most recent works and I showed them to him.” According to Pellan, these conversations were very stimulating, and pointed him in the right direction. Through Picasso’s approach to Cubism, he had found a way to question the academic and conservative attitudes that were still rooted in a dogma of representation. To Pellan, the movement “rejuvenated all of modern art and accomplished a big cleanse.”

Cubist techniques and imagery are as important to Pellan’s oeuvre as Surrealism. Art critic Jerrold Morris, for example, draws attention to the “shallow space” in Pellan’s paintings, which was inspired by the movement. The deconstruction of the forms and flattened perspective in Nature morte no 22 (Still Life no. 22), c.1930, and Fruits au compotier (Fruit in a Fruit Bowl), c.1934, borrow heavily from Cubist principles as well. Furthermore, Pellan often used simultaneous viewpoints, as in Homme et femme (Man and Woman), 1943–47, where the process of spatial fragmentation can be seen in geometric picture planes of contrasting colours, and the bodies of the figures are reduced to flattened shapes.

But as with the Surrealists, Pellan never officially became a member of the group. While he did borrow from Georges Braque (1882–1963), Juan Gris (1887–1927), and Picasso—going so far as to repeat their signature subjects, such as playing cards, bottles, musical instruments, and harlequin costumes—his reluctance to fully commit to pure Cubism is apparent in his work.

Approaches to Drawing and Line

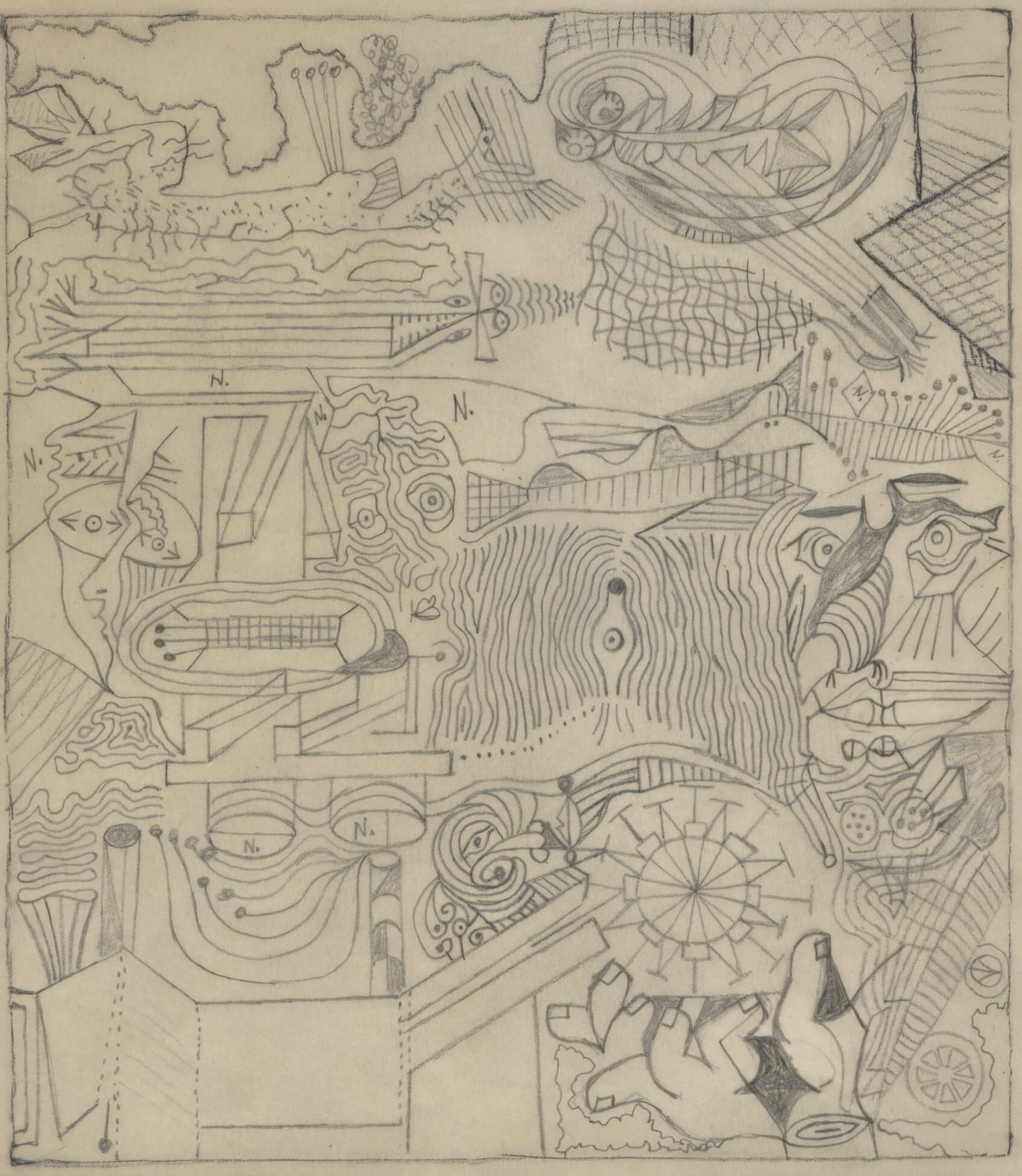

A “born draftsman,” Pellan based most of his compositions, no matter how fantastical or imaginative, on the “solid rock that is the line.” His strong, assertive hand took charge of vibrant colours and worked out the smallest details in an abundance of forms, as can be seen, for instance, in a comparison of the painting Citrons ultra-violets (Ultraviolet Lemons), 1947, and a related drawing. His sketches, whether standalone efforts or ones that have been transformed into powerful canvases, are as recognizable and typically Pellanian as his colour schemes. As one reviewer observed in 1963, “his crazy, complicated, often baroque-like drawing, that’s him, all him.” In fact, the artist always considered drawing an essential element of his art, as the technique also serves as the foundation of any painting. This explains why he was first attracted to the Parisian group Forces Nouvelles, although he later rejected their traditionalist bent in favour of the more radical perspectives inherent to Cubism and Surrealism.

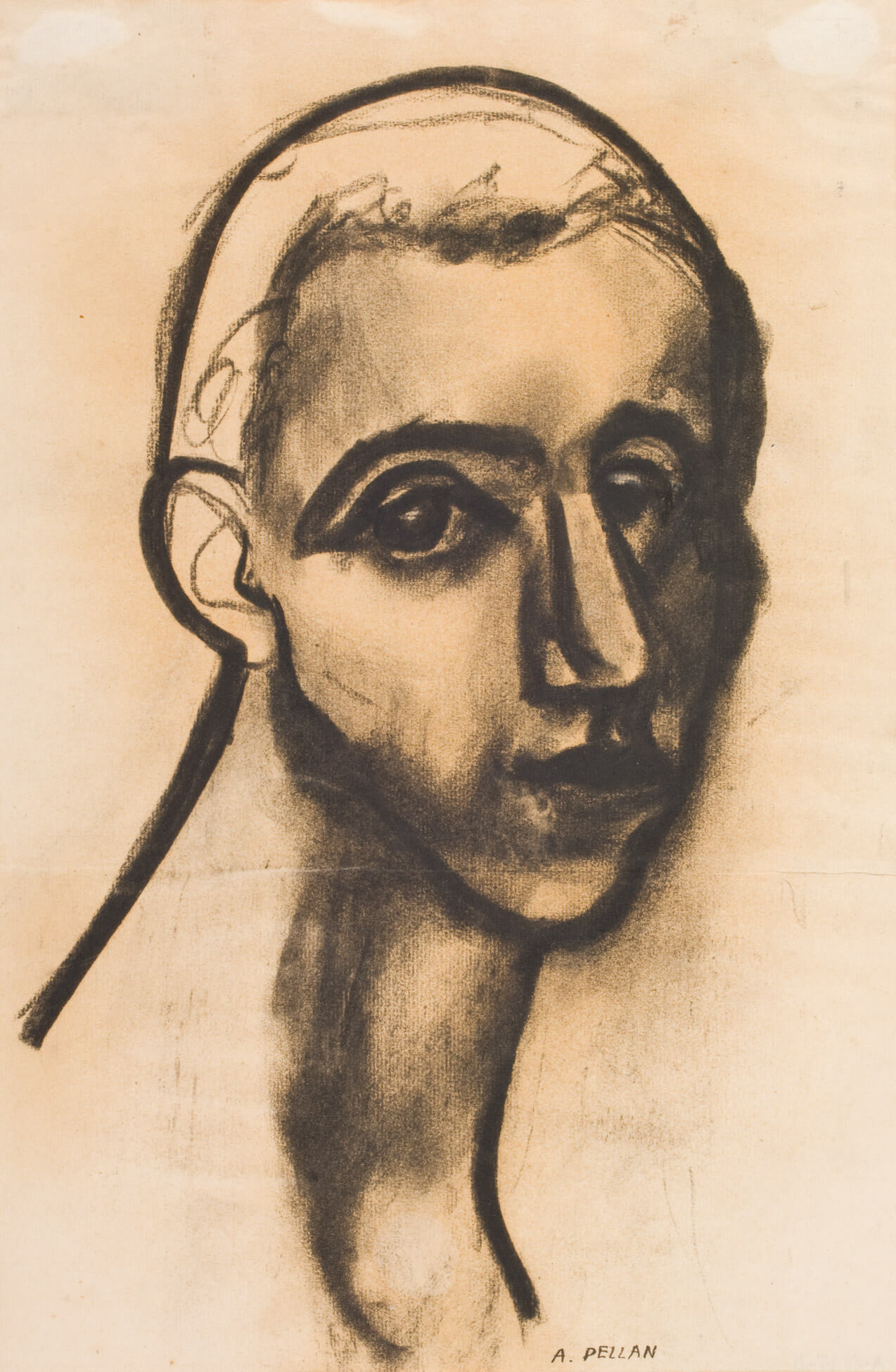

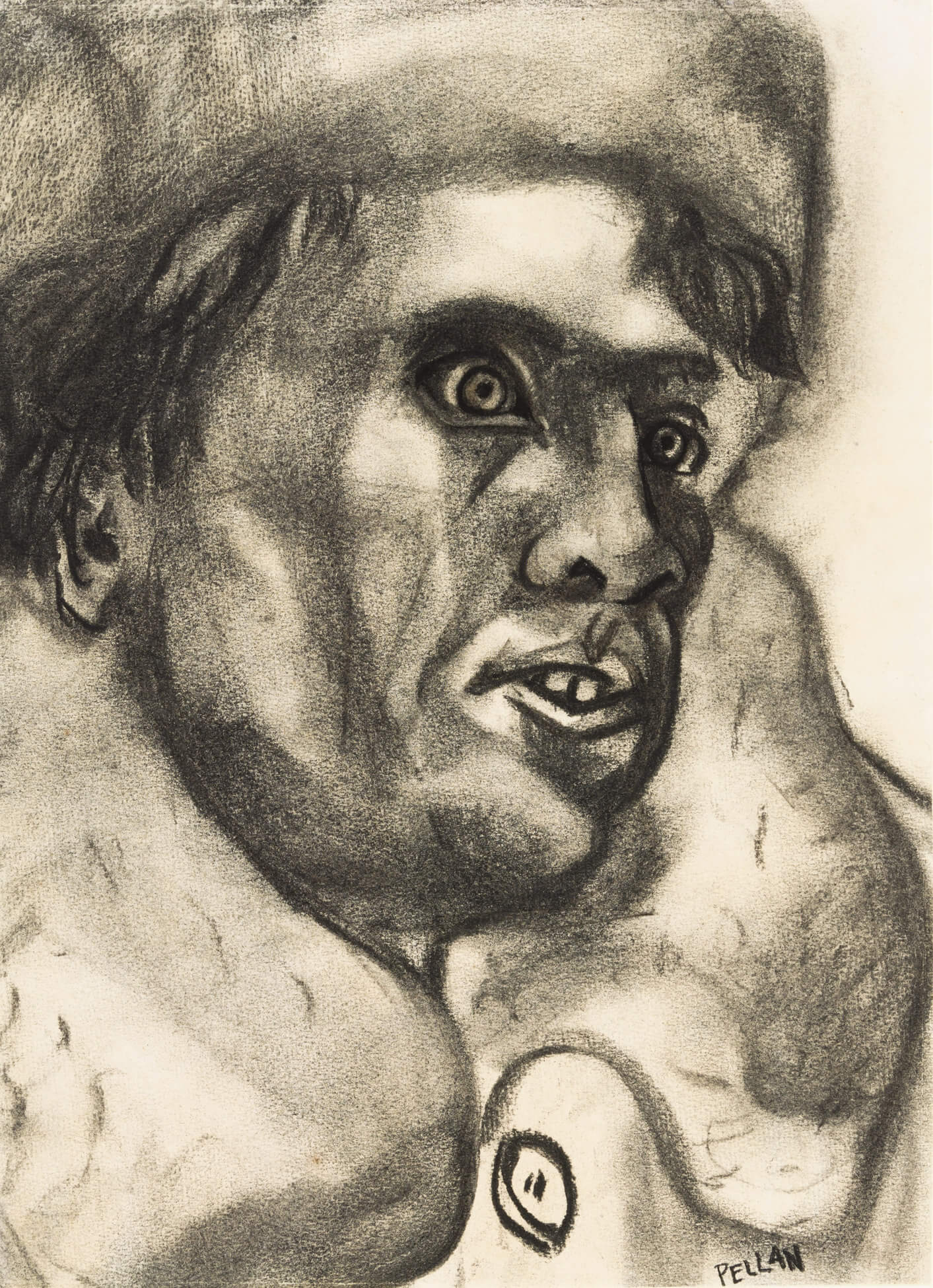

Art historian Reesa Greenberg has identified that Pellan’s drawings can be divided into five periods: the first encompassing his time at the École des beaux-arts in Quebec (1921–26); the second during his sojourn in Paris (1926–40); the third spanning the years between 1940 and 1944; the fourth lasting from 1944 to 1952; and the last taking place after 1952. Sadly, only four sketches from his early period (all emblematic of his academic training) remain. The drawings Pellan produced until midway through 1944 reflect this classical approach, although he was beginning to pull from the new ideas he encountered in Paris.

While Pellan started to make work with simpler subjects in the 1930s, he still took time to create precise forms. He also paid close attention to the effects of light and shadow, volume, and line, as can be seen in Autoportrait (Self-Portrait), 1934, Portrait de femme (Portrait of a Woman), c.1930, or Jeune homme (Young Man), 1931–34. Fillette de Charlevoix (Young Girl from Charlevoix), 1941, and Femme à la causeuse (Woman in a Loveseat), 1930–35, are delicate line drawings, whereas Pellan experimented with ink and charcoal in extensively worked studies such as Tête de jeune fille (Head of a Young Woman), 1935, Le bûcheron (The Lumberjack), 1935–40, and Tête de jeune fille no 126 (Head of a Young Woman no. 126), 1935–39. Yet these drawings were more personal than his academic studies of the 1920s, due in part to the artist having come to prefer a drawing style centred on few precise lines, or a “simple pen tracing” in which “synthetization is pushed to the extreme.” Femme (Woman), c.1945, is a perfect example of this approach: Pellan creates a stunning portrait out of a few lines, with dark patches of charcoal building the woman’s body and shaping her face. While we can see the artist’s classical training in the core technique, the geometric shadows clearly show his allegiance to modern art—in this case, to Cubism.

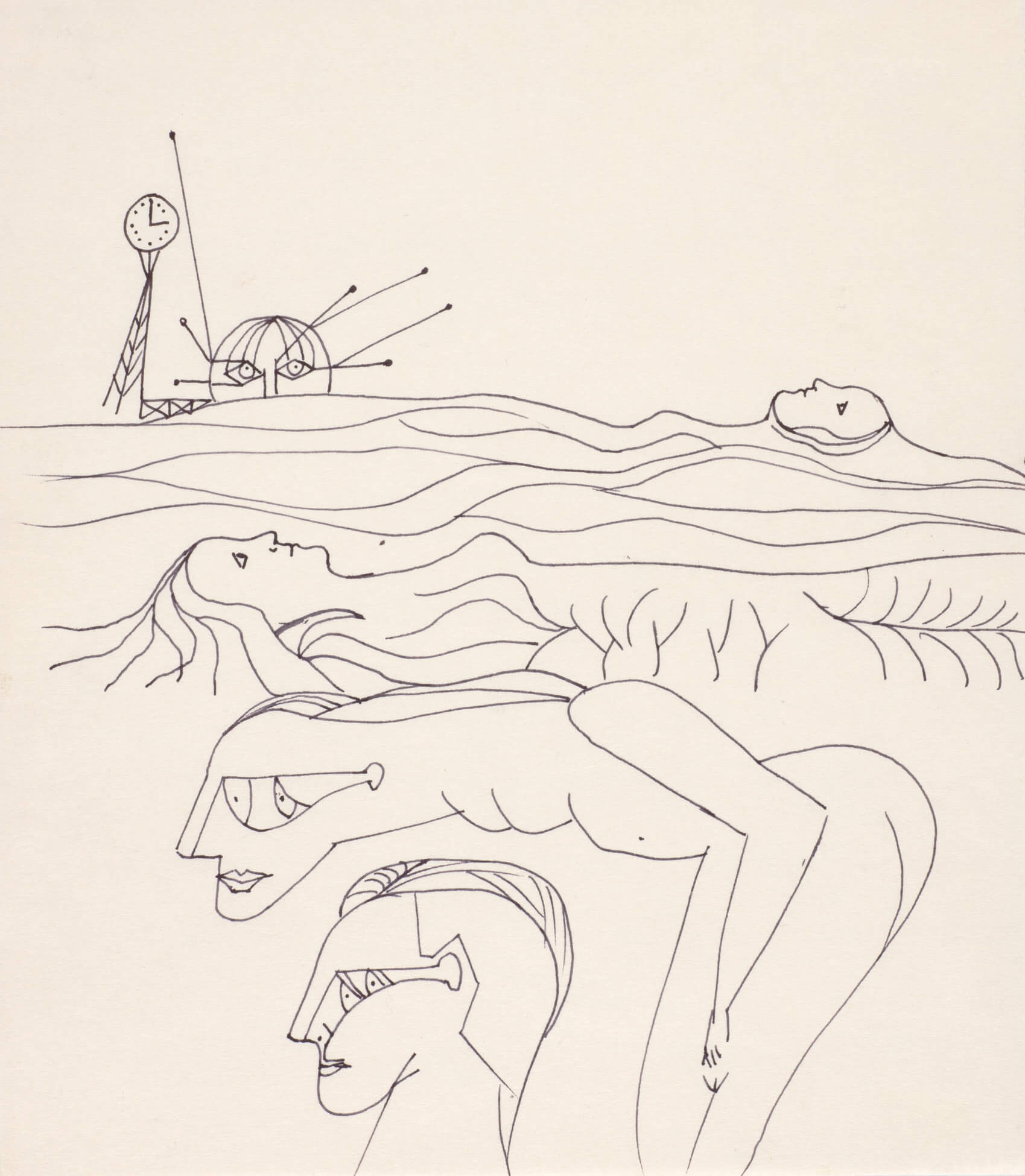

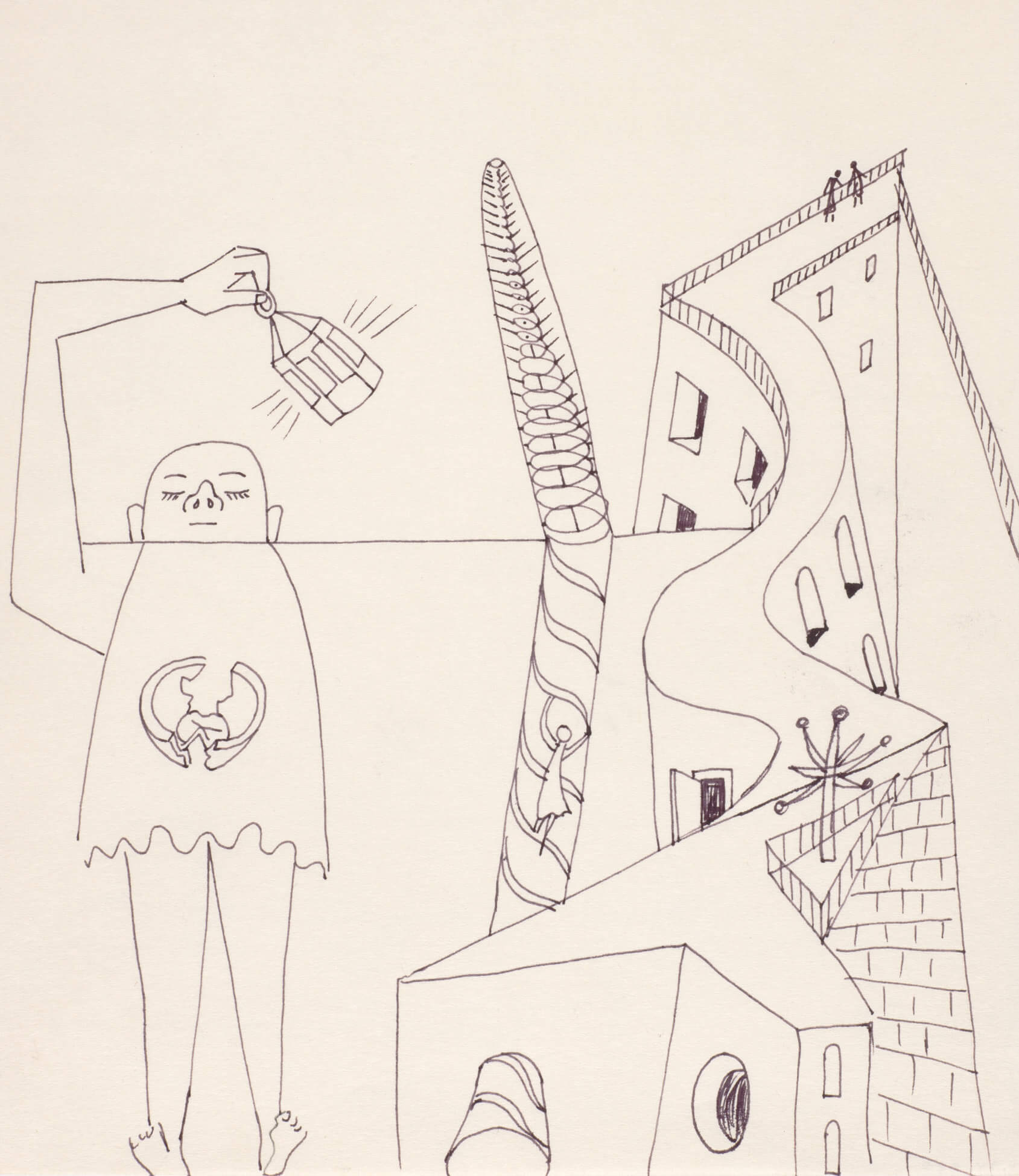

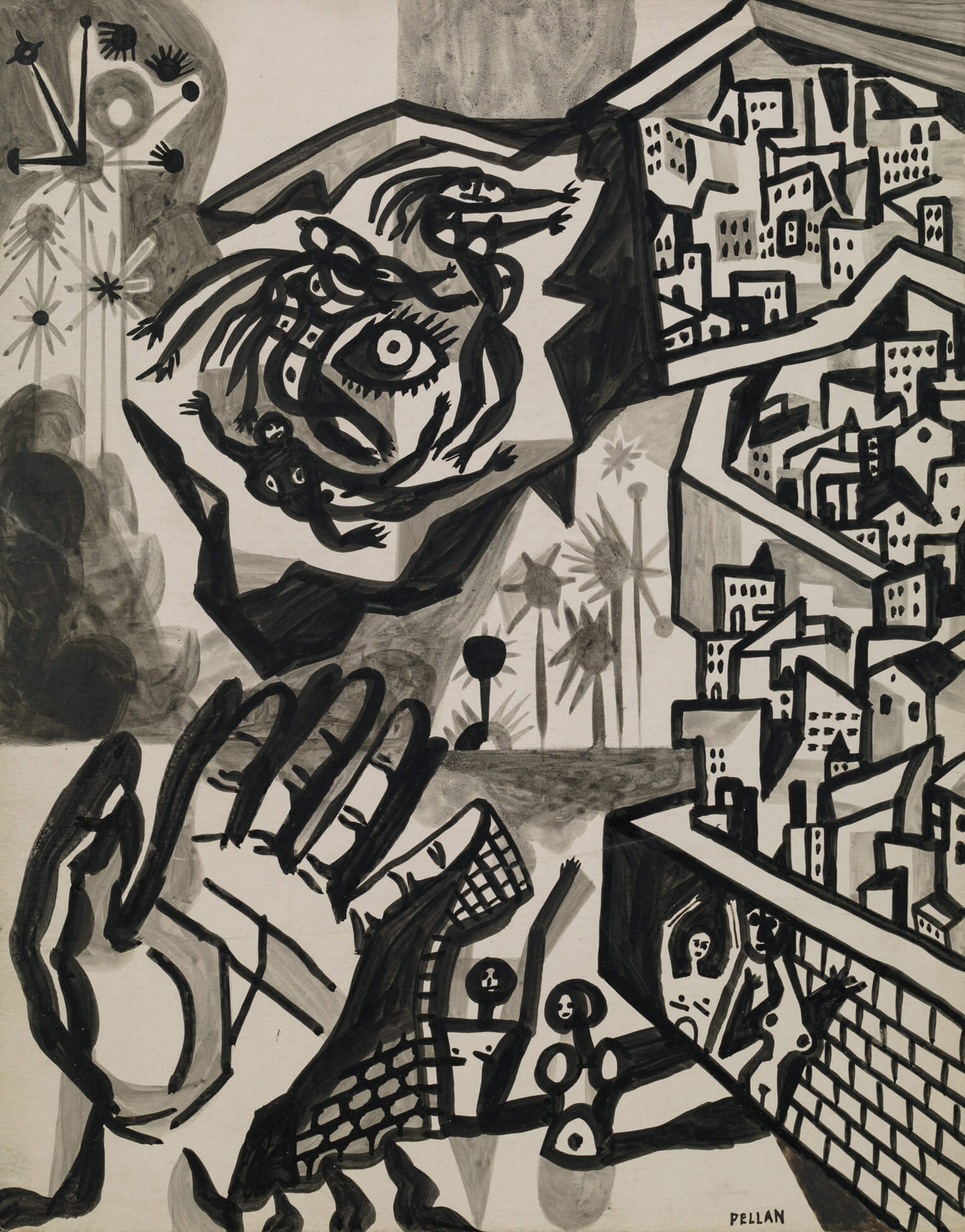

In the mid-1940s, Pellan abandoned traditional subject matter almost entirely. He increasingly drew on a vocabulary of double and hybrid images, symbols that evoked love, dreams, and metamorphosis, and Surrealist poetry. These drawings depict a weird world in which emotionally charged objects might trigger feelings of discomfort or anxiety in viewers, an effect illustrated by the distorted bodies and dizzying spaces in Femmes paysage (Women Landscape), c.1945–75, and Personnage avec édifice labyrintesque (Figure with a Maze Building), c.1945–75.

Compared with the sketches he realized in the 1930s, Pellan’s later drawings “employed all-over compositions, marked contrasts of black and white and non-descriptive pattern, all of which give the impression of energy and movement.” His single lines—already “pure, vibrant, solitary, naked, simple, energetic”—became fragmented. As well, he did not hesitate to paint his drawings, a practice that, according to Greenberg, transformed the artist’s entire working process. The drawings Pellan realized in the 1950s and beyond became even more diverse. Those executed in ink, for example, “convey a growing interest in the techniques of calligraphy and the compositions of Indigenous art.”

Approaches to Colour

Pellan’s devotion to intense and luminous colour was at the heart of his creative personality. His unique world of colour was “highly emotional and brilliant, sometimes to the point of crudeness,” and his seemingly “unrefined” and sometimes even “violent” palette brought his paintings to life. In earlier work, such as Pensée de boules (Bubble Thoughts), c.1936, Femme d’une pomme (Lady with Apple), 1943, and Floraison (Blossoming), 1944, his complicated compositions were dominated by strict lines. But as time passed, Pellan began to simplify his drawings, giving more primacy and attention to his experiments with colour. These explorations had pronounced effects on his work: they could unify a scene or create stunning zones of contrast, and they also produced a certain rhythm that imbued his paintings and graphics with a sense of movement. In Le buisson ardent (The Burning Bush), 1966, for instance, shades of red create connection through the composition and map out a visual path for the eye to follow.

At his landmark 1940 exhibition, Exposition Pellan, in Quebec and Montreal, Pellan’s colourful excess astounded critics and spectators alike. Some called his canvases “feasts of colours,” upon which the “most surreal but harmonious shades” stand out and interact with one another. Others mentioned the range of his palette, poetically describing how it “sings of light in the most incredible, most astounding rhythms,” while a sense of mystery seemed to “move the very soul.”

When asked about his creative breakthroughs, Pellan declared “My colours are luminous without being fluorescent. They are vibrant. Sometimes in a photograph the camera pictures a halo around them.” In fact, the artist wished to create “electric” paintings, paintings that were “so very lively that [they] appeared as if phosphorescent.” By juxtaposing bold colours, he achieved a kind of potency that became characteristic of his style. As the critic Maurice Gagnon observed, Pellan’s colour “shines, erupts, vibrates and resonates with intensity.”

Working Across Media

In an interview with journalist Judith Jasmin in 1960, Pellan pointed out that the lines separating painting, architecture, sculpture, and illustration were beginning to disappear in contemporary art, a tendency he welcomed. Diverse in his artistic research, the artist did not simply experiment with painting and drawing, but tried “to do everything.” This versatility was not always applauded, since some critics doubted the quality of pieces that diverged from what was accepted as Pellanian. However, his body of work is unique precisely because it employs many different media.

Pellan worked on illustrations as well as his paintings: some were a synthesis of an idea, simplified to the extreme, while others were highly elaborate designs and patterns, intended to illustrate manuscripts by poets such as Alain Grandbois (Les îles de la nuit [The Isles of the Night], 1944), Éloi de Grandmont (Le voyage d’Arlequin [Harlequin’s Voyage], 1946), and Claude Péloquin (Pellan, Pellan, 1976; Le cirque sacré [The Sacred Circus], 1981). The verses of these writers were often infused with the same Surrealist spirit as his paintings. In fact, Surrealist Quebecois poetry had helped cultivate the fantastic images in Pellan’s graphic dream worlds.

Beyond those aspects of his oeuvre, Pellan created “unforgettable costumes” and scene decorations for the theatre productions Madeleine et Pierre (Madeleine and Pierre) (1944) and La nuit des rois (Twelfth Night) (1946/68). Breaking with the naturalistic tradition that clearly evoked the space and time in which a particular play was set, these two collaborations sparked Cubist- and/or Surrealist-infused universes in which Pellan mixed architectural styles, geometric patterns, deconstructed spaces, and multiple perspectives. For both shows, he created costumes based on a deep psychological analysis of the characters. This approach illuminated not only Pellan’s talent as painter but also a “dramaturgical sensibility” that was necessary for this curious fusion of theatrical text and image.

Pellan also produced a great number of murals for private homes and businesses, as well as for the public sphere, most famously in Sans titre (Canada Ouest) (Untitled (Canada West)) and Sans titre (Canada Est) (Untitled (Canada East)), 1942–43. Murals have certain qualities that set them apart from other modes of artistic expression. For Pellan, their public nature was of particular interest, as he believed the cold and neutral character of modern architecture invited decoration. These surfaces called for large-scale art that sought to “beautify.” A study for a stained-glass project from 1960 shows the measure of detail, thought, and inventiveness involved in Pellan’s decorative work.

Between 1968 and 1980, Pellan completed around seventy-five engravings. He increasingly experimented with large-scale prints that accentuated the graphic character and two-dimensionality of smaller paintings he had created in his earlier years. Striving to emphasize the colour of the pieces, he often simplified and reorganized forms, as can be seen in Voltige d’automne – A (Autumn Acrobatics—A), 1973.

He also created many curious objects. Evoking the art of assemblage, Pellan’s Satellites, 1979, were mobile sculptures, designed to be hung. They were composed of various assorted objects that the artist glued together using a kind of silver spray paint. A vacuum-cleaner hose, a sink stopper, shells, a plastic banana, and door handles were among the articles that went into the making of these strange creations. Pellan’s Mini-bestiaires (Mini-Bestiaries), 1971–75—fantastic creatures that also inhabited his paintings—were small, painted stones onto which the artist grafted legs, horns, and tails made of cotton swabs or plaster. Predominantly products of Pellan’s imagination, these tiny beasts were painted in bright colours and decorated with whimsical motifs that bore the stylistic mark of their creator. Finally, his playful shoe-objects, 1974, embrace Surrealist theories of the poème-objet—combining poetry and object, the technique was an effort to recreate things seen in dreams—and the merveilleux, a way of looking at the world that finds the marvellous in everyday life.

Branching out into other forms helped Pellan fuel his creativity. By working across media, he explored new ways of expressing himself and experimented with styles. A new genre or format imposed certain novel constraints and eliminated others, allowing Pellan to think laterally and take risks. Even so, the artist built connections between different pieces and even across media. He explored how a single subject can be represented in multiple ways, returning to earlier paintings for inspiration in his later graphic projects and occasionally drawing on his evolving skills to create new companion works.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements