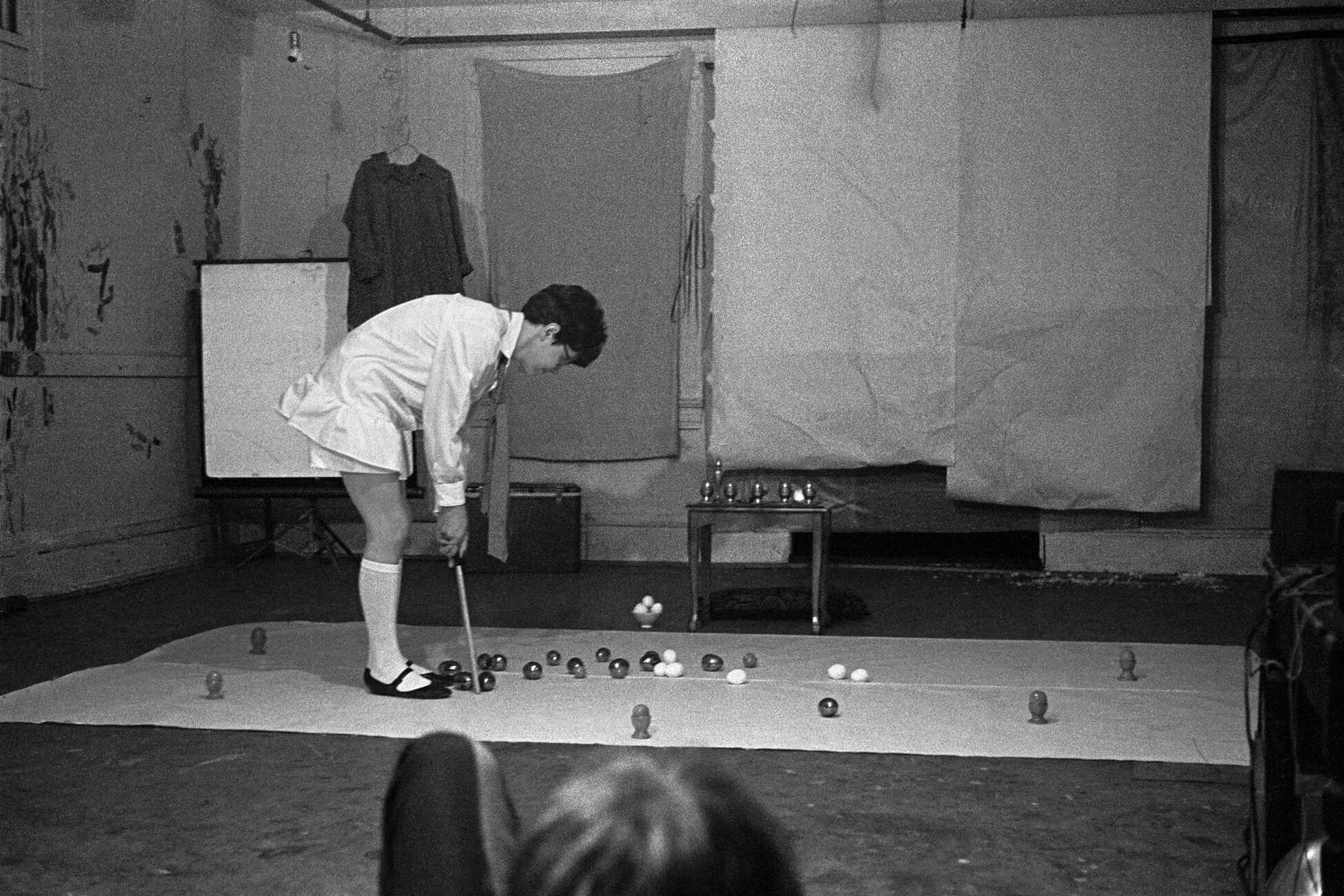

Some Are Egger Than I 1969

Gathie Falk, Some Are Egger Than I, December 31, 1969

Performance at the New Era Social Club, Vancouver

Photograph by Michael de Courcy

Gathie Falk’s Some Are Egger Than I was first performed in 1969 at the New Era Social Club (an informal artists’ society in Vancouver from the late 1960s until 1972), beginning with the artist sitting atop a black and red pillow. Other props included a red table with a bowl of cooked eggs, and raw and gold ceramic eggs scattered on the floor. When the action began, Falk chose an egg, put it in an egg cup rimmed in gold, and ate it, before picking up a ruler that she used to bat a ceramic egg across the floor in the direction of a raw egg, which would then smash. These activities were repeated in order until all of the real eggs were eaten or broken. In later performances of this work, presented after Falk was documented participating in the Douglas Chrismas piece Eighty Eggs, 1969, an interdisciplinary element was introduced, with slides of Falk—wearing a long gown and work goggles while being intermittently pelted with raw eggs—projected behind this live activity. Falk had been experimenting with performance art since she participated in a workshop led by Deborah Hay (b.1941) in 1968, and Some Are Egger Than I became one of her well-known creations.

Eggs are a recurring element in Falk’s work. They feature in other performances—in Orange Peel, 1972, they are wrapped; in Drink to Me Only, 1971, they are piled up; in Low Clouds, 1972, they are sliced and consumed. They also appear in other works, such as the ceramic Two Egg Cups with Single Egg, date unknown. While there can be an impulse to associate Falk’s use of eggs with Christian symbology because of her Mennonite faith, interpreting them as symbols of fertility, resurrection, or eternal life, what they mean to Falk, she has insisted, is personal rather than universal. She has recounted the early childhood memory of being given an egg every afternoon to take to the store to exchange for candy. Eggs were among the first things she made when studying ceramics because she liked their shapes. They are objects that feature in her daily life, and she finds beauty in them.

While Falk’s work in performance can seem incongruous with the rest of her oeuvre, the visual and physical structure of Some Are Egger Than I makes it clear how all of her work is aesthetically and compositionally linked. Just as in her painting and ceramic work, in this piece we are presented with elements that walk a fine line between metaphor and banality. Falk has retrospectively described this piece, produced at the height of the Vietnam War, as a kind of “war game”—she sees the calm consumption of the cooked eggs interspersed with rounds of her ruler smashing the defenseless raw ones as analogous to the detachment with which military leaders approach battle.

In “To Be a Pilgrim,” art critic Robin Laurence notes the rarity of this direct politicism in Falk’s work, suggesting that the only other time it occurs in her mature practice is in the Hedge and Cloud series, 1989–90, in which the artist documents the ships she had seen anchored in Vancouver’s English Bay on her daily walks with her dog, as can be seen in There Are 21 Ships and 3 Warships in English Bay, 1990. Falk, who is a pacifist as per her Mennonite beliefs, was dismayed that among the barges, freighters, tugboats, and cruise ships were U.S. Navy warships carrying nuclear weapons, and in the series she calls attention to the military presence amid the otherwise benign activity of the natural harbour.

There is at least one other political work in her oeuvre—in her 2018 memoir Apples, etc., Falk recounts making a 2-metre-tall ceramic sculpture entitled The General Explaining Why He Had to Use Napalm, 1965, while studying with Glenn Lewis (b.1935). It stood outside the University of British Columbia education building for several months, providing Falk with an outlet for her anti-war sentiments that suited her temperament better than demonstrating.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements