Gathie Falk’s practice embodies ideas, principles, imagery, and ways of engaging with the world that are unwaveringly part of her philosophy of being. Her careful and deliberate approach makes plain the simple beauty and elegance of daily rituals and commonplace objects. She applies discipline to interdisciplinarity and draws on surreal collisions of unorthodox elements to manifest the spectacular visions she sees in her mind’s eye. Grounded in her surroundings, she often includes her friends and neighbours in her work, and she is an influential and stalwart figure in the Vancouver art community.

The Veneration of the Ordinary

The overlooked aspects of daily life provide Falk with a wealth of inspiration, and she treats them with a sense of special significance in her work. She credits artist Glenn Lewis (b.1935), her ceramics teacher at the University of British Columbia in the 1960s, with first introducing her to what he termed “the art of daily life.” Falk once characterized her approach as the “veneration of the ordinary,” but later she pushed against people’s tendency to equate the ordinary with the banal, putting forward this query: “By the way, I painted the ocean; I painted the night skies, quite a few times. Is that ordinary? Or is that extraordinary? A piece of the ocean—is that ordinary?”

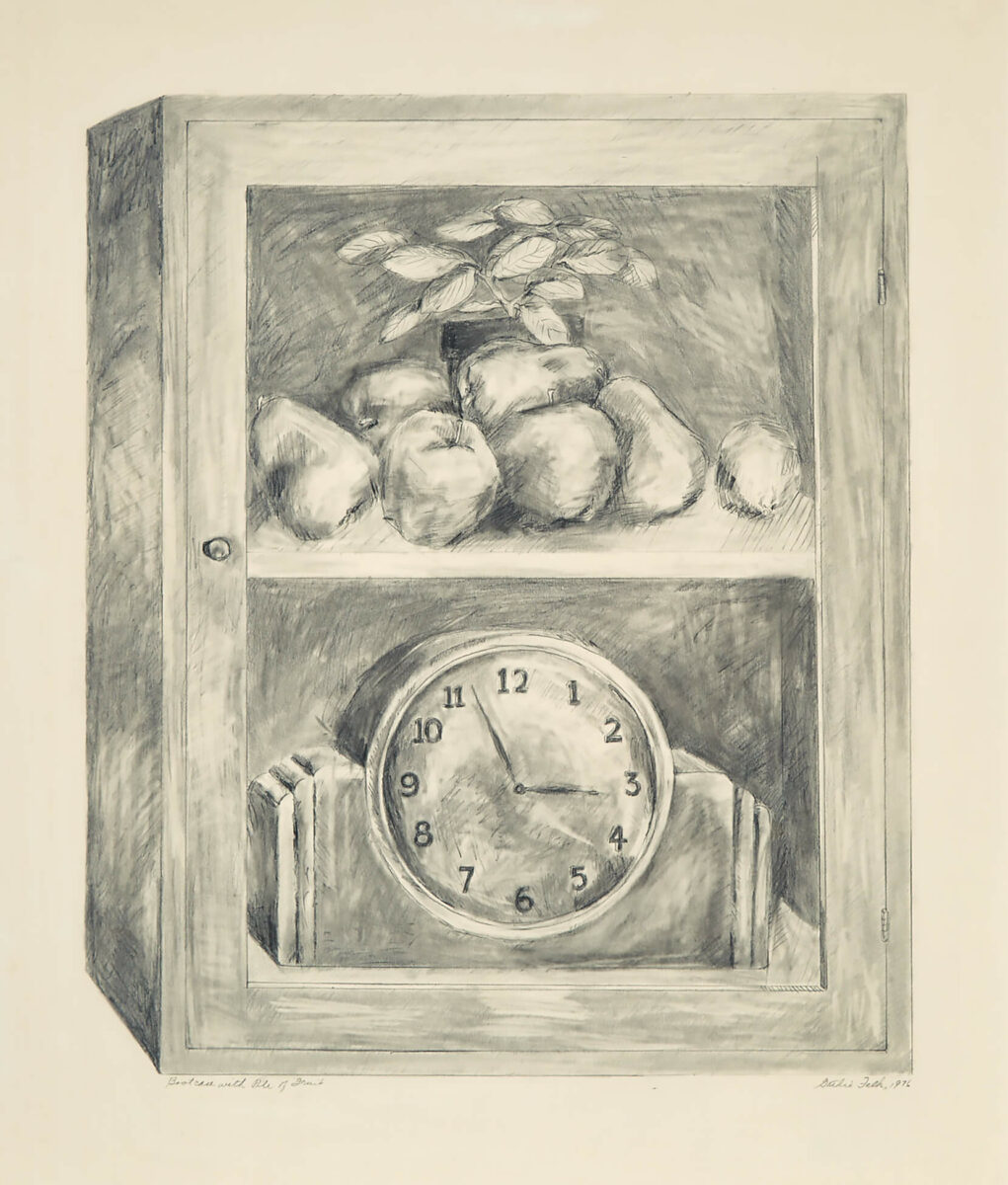

Falk’s axiom describes an elevated appreciation of the so-called ordinary things around her. Reviewer Joan Lowndes recognized this when, in reference to the suite of Falk’s 39 Drawings exhibited at the Bau-Xi Gallery in Vancouver in 1976, she compared the artist’s work to that of eighteenth-century French still-life master Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin (1699–1779), noting that in Falk’s “reverence for… humble everyday things… she transforms them into icons”—an interest evident in works such as Bookcase with Pile of Fruit, 1976.

Falk has noted, “Most of my work is a good deal removed from reality, but it undoubtedly has roots in my daily living.” This is not as pithy a description as “veneration of the ordinary,” but perhaps it is more fitting. Falk describes her Night Skies, 1979–80, and Pieces of Water series, 1981–82, as paintings that might be considered as “personal realism, because they represent my personal and emotional response to my environment.” She is quite right to assert the extraordinariness of these subjects.

Falk has been connected to Pop art, the movement that started in the 1950s and incorporated imagery from popular culture in a fine art context, due to the affinities between her breakout installation Home Environment,1968—which included ceramic renderings of domestic items, such as a TV dinner—and works such as Bedroom Ensemble, 1963, by Pop artist Claes Oldenburg (b.1929). However, Oldenburg and his peers were motivated by an interest in infusing high art with popular mass culture, while Falk was interested in making art about the things she was personally connected to. Distancing herself from the movement, she has written, “What I made, and still make, is more personal and less slick—more modest, I believe, and more obviously handmade.” Falk’s touch is evident in works such as Cherry Basket, c.1969, and Small Purse, c.1970.

Falk’s Fruit Piles, 1967–70, and Single Right Men’s Shoes, 1972–73, were in some ways prompted by her interaction with mass production and its retail outlet; however, her connection to the merchandise was not made through the lens of consumerism but instead through her routine experiences of her home, garden, neighbourhood, and friends. The everyday was a resource and inspiration for her work.

Falk’s friend and collaborator Tom Graff (active from the 1970s) has described how the veneration of the ordinary infused her performance work. “As she sets up a tableau or sculptural stage, there is a kind of contingent system which touches all sides,” he said. “Body and props are one, if you will. Even the stage is not a platform, it is an integral element, part of the collections of things and milieu.” This approach is what has enabled Falk to move from one medium to another so effortlessly, as it offers a philosophy for conceptualizing and making work that is rooted in the artist’s experiences and her audience’s easy identification with them. In Falk’s art, many motifs reappear in different media—for instance, shoes appear in the performance Skipping Ropes, 1968, the sculpture Eighteen Pairs of Red Shoes with Roses, 1973, and the silkscreen Crossed Ankles, 1998, to name only a few projects.

Because she turned away from teaching, it is difficult to argue that Falk has had direct aesthetic or stylistic influence on subsequent generations—she stopped teaching elementary school in 1965, and she returned to the profession only briefly in 1970–71 and 1975–77 when she taught visual art part-time at the University of British Columbia. Yet, it is inarguable that in her commitment to “the art of daily life” she has contributed to the creation of a kind of space that has allowed art and life to merge in extraordinary ways. Numerous Vancouver artists—among them Derya Akay (b.1988), Zoe Kreye (b.1978), and the collective Matriarchal Roll Call (formed in 2014)—now inhabit that space, working in interdisciplinary ways that make perfect sense in the wake of Falk.

Discipline, Interdisciplinarity, and Series

Falk’s work of the 1960s and early 1970s was clearly inspired by her observation of collections of items in retail settings—one need only look to her pyramids of apples in Fruit Piles, 1967–70, or neatly arranged boots in Single Right Men’s Shoes, 1972–73. Contrary to the tendency emerging at the time in the Pop art movement to incorporate the methods of mass production that would have so readily connected to her choice of subject, Falk’s works are executed in a manner that evokes the artist’s hand and her relationship to the things she depicts. Her goods read not as neutral commodities but as objects that Falk has a connection to.

In 196 Apples, 1969–70, for instance, each piece of fruit was similar but unique. “For most of the sculptures I’ve made I have wanted to have soft, undulating surfaces,” Falk has written. “I wanted them to look as though they were alive: living breathing objects. Clay is the best thing for that.” The exercise of executing the Fruit Piles series, and other works of intricate conception or composition—whether in performances, such as Red Angel, 1972, or installations, such as My Dog’s Bones, 1985, or Herd I, 1974–75—are testaments to the discipline with which Falk carries out her practice.

Falk’s discipline in the studio is also evident in her paintings, such as the Theatre in B/W and Colour works, 1983–84, which she consistently created as part of a series. Insight into the commitment at the root of Falk’s inclination to work in the serial format is evident in a recorded conversation from 1984 between the artist and then curator of the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Nicholas Tuele. Falk notes, “It always seems to me that I can never get everything said in one painting. If I do one painting it always leads to other ways of doing a similar kind of thing, and so I just keep on working until either there is a show, which stops me and then another show coming up after that which has to be different…”

The degree of Falk’s focus and commitment to her subjects became very clear when she moved away from performance art and ceramics and returned to painting in 1977, first with the Border series, 1977–78; then Thermal Blankets, 1979–80; Night Skies, 1979–80; Pieces of Water, 1981–82; and so on. Sometimes, as in the Border series, which depicts the edges of her and her neighbours’ gardens, the multiple format enables an investigation into an image too expansive to be reduced to a single canvas. At other times, as with the Pieces of Water series, in which Falk paints the surface of rectangular segments of the ocean as seen on her daily walks, the sequential structure reflects Falk’s desire to communicate her ongoing relationship with the subject matter. Both Night Skies and Pieces of Water essentially became series of series, as Falk would return to the subjects of the skies at night and the ocean again later in her career.

The discipline with which Falk commits to these large or serial projects has meant that she usually works with one medium or another at a time, but the result of her facility with different materials means that she has constantly built up new vocabularies with which to describe the mental imagery that drives all of her work. Hence, while much is made of the 1977 resignation of her performance practice and return to painting, Falk has continued to work in a range of mediums, including ceramic, papier mâché, cast bronze, and photography, as her ideas demand.

There has long been a strong narrative of interdisciplinarity in the Vancouver art community, and one of its threads traces back to Intermedia, the artists’ association founded by Jack Shadbolt (1909–1998) and Glenn Lewis in 1967, of which Falk was an active and enthusiastic member. A powerful presence of interdisciplinary artists remains in the city—among them Carol Sawyer (active from 1990), Laiwan (b.1961), and Cindy Mochizuki (b.1976)—who have emerged from Vancouver’s institutions of formal cross-medium training (namely Simon Fraser University’s School for the Contemporary Arts, in the case of these artists) and the informal spaces of community learning established by Falk, Lewis, Shadbolt, and their peers.

Collaboration and Community

The kind of collaboration and community engagement so readily recognized as an artistic medium today was started from necessity in the 1960s and 1970s, when Falk was first launching her career. Artist-run centres and practices emerged as artists searched for ways to support each other in making and showing work. When Intermedia, a non-profit society that provided Vancouver artists with an interdisciplinary meeting place, was founded in 1967, Falk became deeply involved.

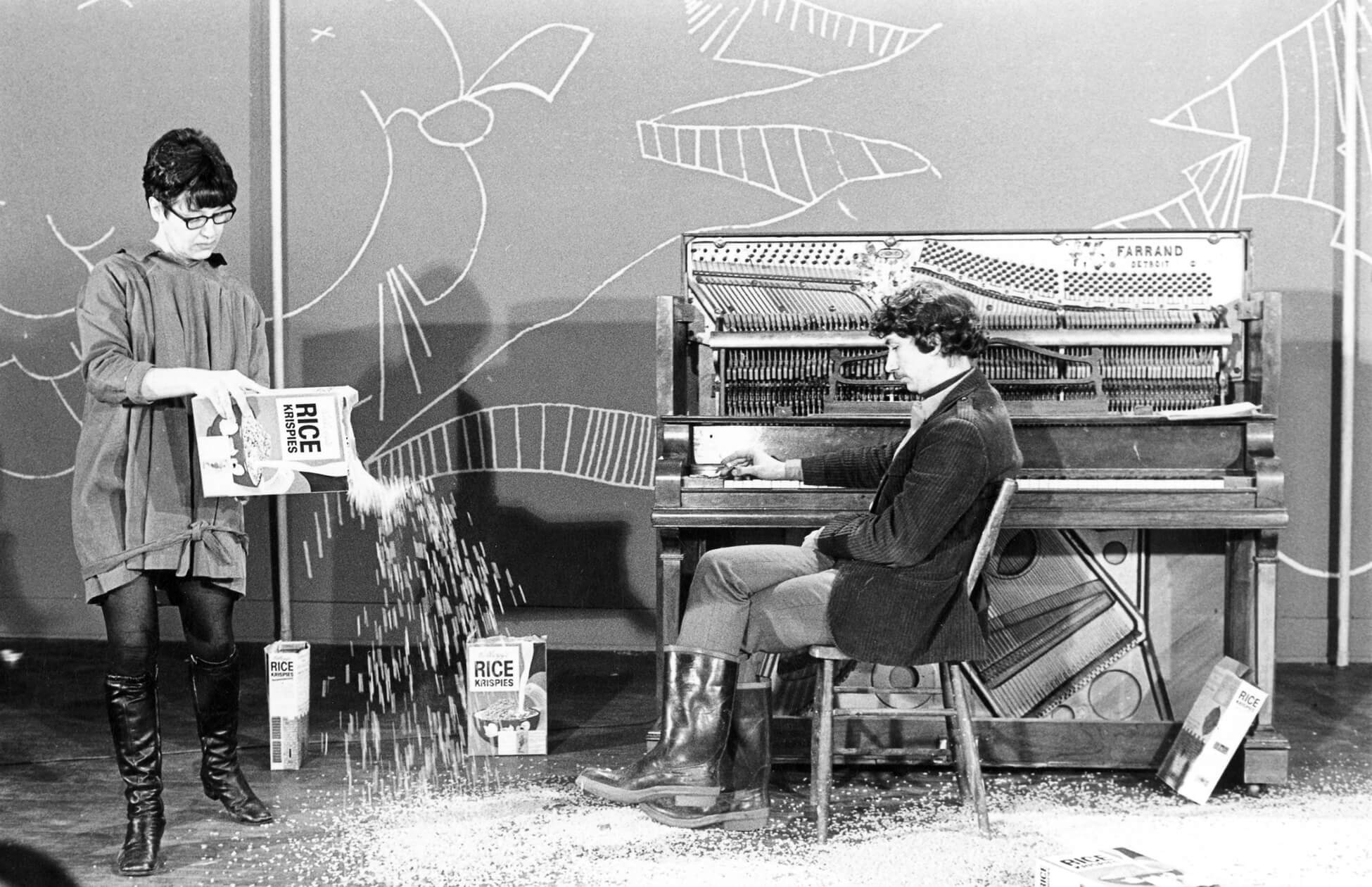

It was through Intermedia that much of Falk’s performance work was developed and presented to an audience; these programs often took place at the Vancouver Art Gallery. Falk’s ceramics teacher and friend Glenn Lewis was a founding member of Intermedia, and she also met and became good friends with other artists during this period, such as Tom Graff, Michael Morris (b.1942), Glenn Allison (active from the 1960s), and Salmon Harris (b.1948). Falk not only created her own performances with her peers, but also participated in their works, such as Lewis’s Rice Krispie Piece, 1968.

After a few years of taking continuing studies painting courses while earning a living as a teacher, Falk extracted herself from classes in 1962, asserting that she no longer wanted someone standing behind her telling her what to do. She did, however, very much want to belong to a community of artists. She had been raised in a setting where friendship and social life came to her through her church, but increasingly her close friends were to be found in the art world, as she began exhibiting her work and developing relationships with teachers, mentors, fellow artists, collaborators, dealers, critics, writers, and collectors.

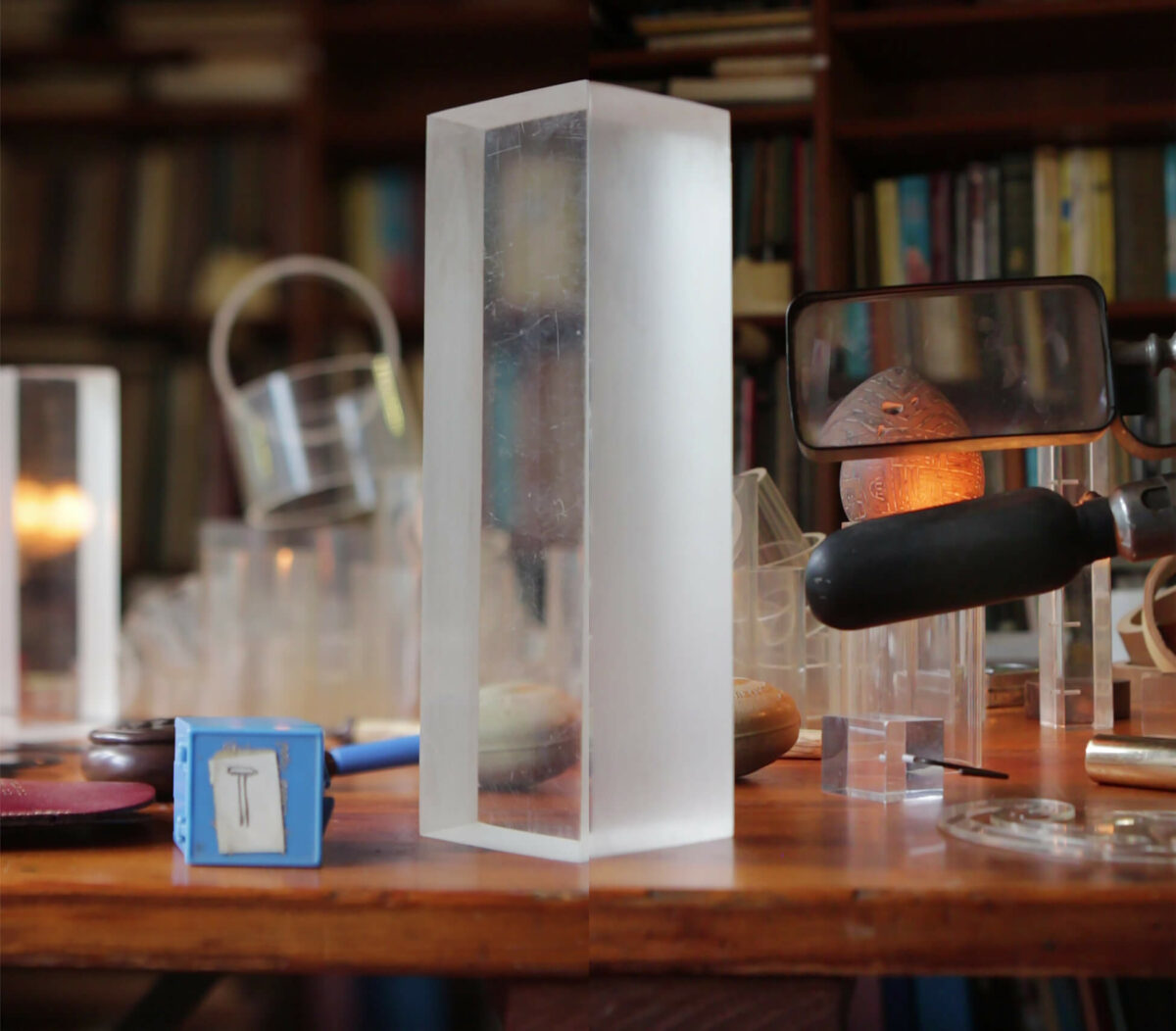

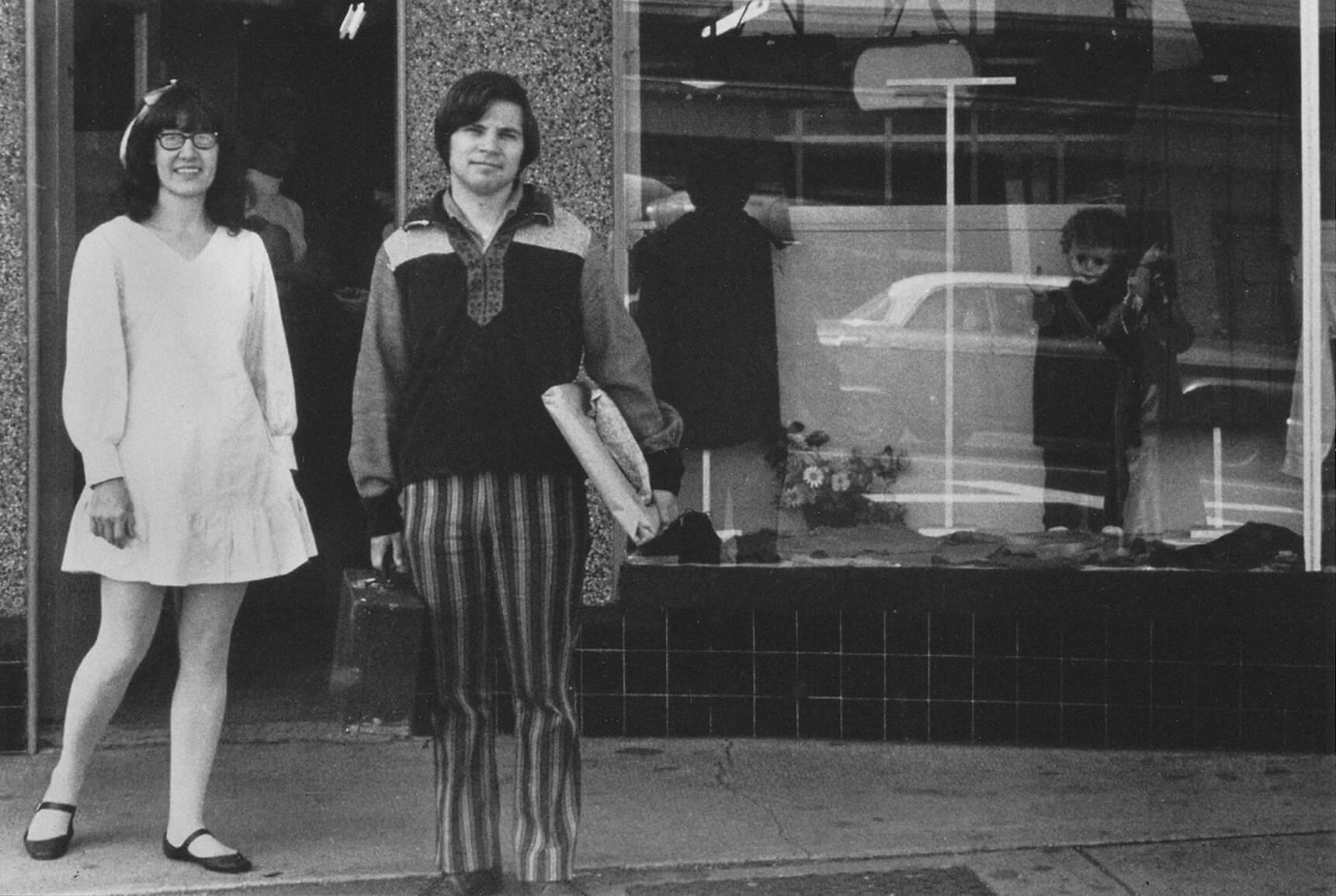

While much of Falk’s work is produced in her studio by her hand alone, she has always executed certain projects with the aid of her friends. For instance, in the summer of 1971, Falk set off on a cross-country train trip with her friends and fellow thrift-store devotees Tom Graff and Elizabeth Klassen, with the intention of visiting second-hand stores across Canada. In her 2018 memoir Apples, etc., Falk describes how they approached their travels as a kind of Conceptual art project, even though she notes that they did not think of it as such at the time. In every store they visited, they searched for the best, worst, and most engaging objects, documenting their finds and taking snapshots of themselves in front of each shop.

Graff and Klassen have remained close friends with Falk, and while Falk is an artist with a singular vision, it is important to recognize how many individuals, particularly these two, have been integral to her work in certain ways.

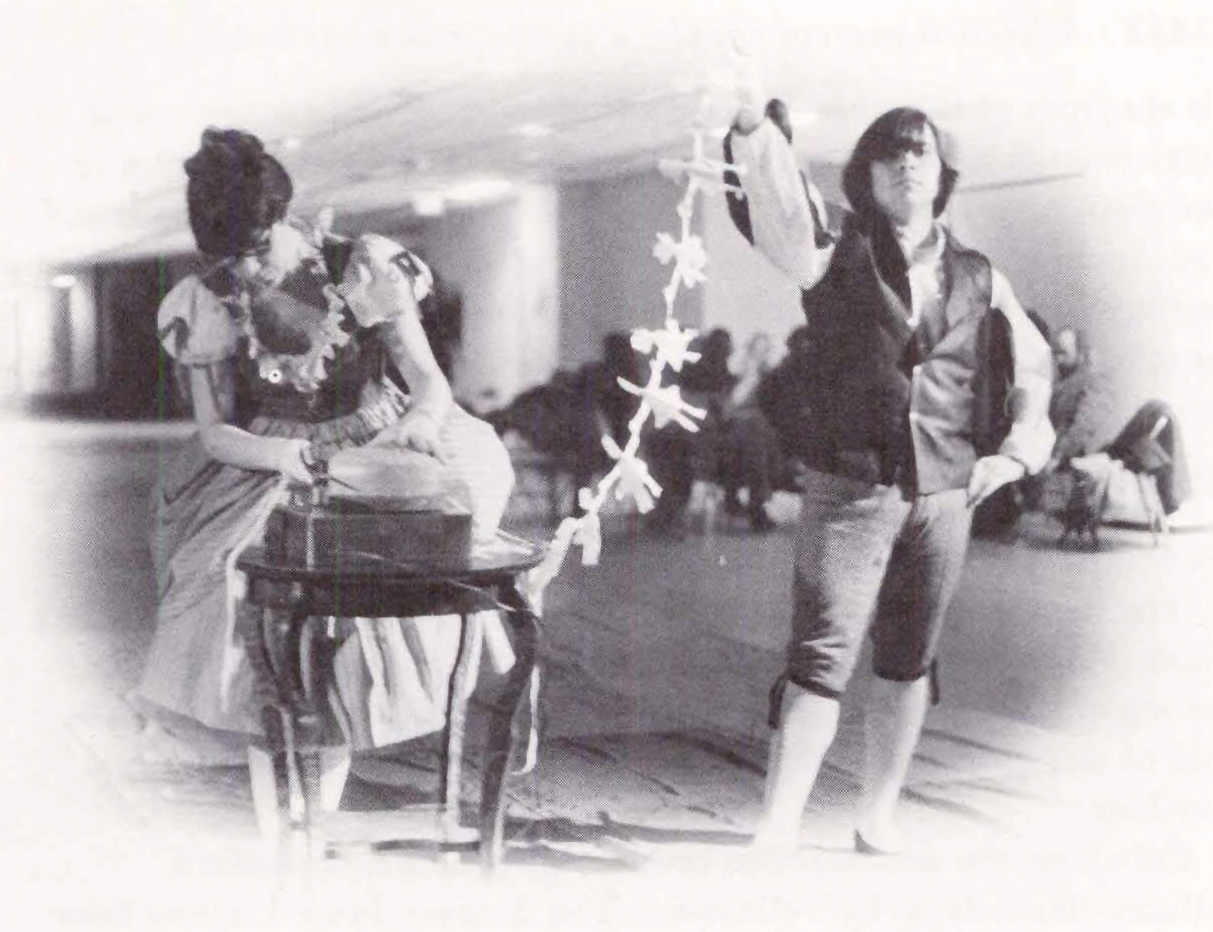

Graff is a Vancouver-based artist, writer, and curator. He and Falk were regular collaborators in their performance work: Cake Walk Rococo, 1971; Cross Campus Croquet, 1971; and Ballet for Bass-Baritone, 1971, were all performances that Falk developed with Graff. Ballet for Bass-Baritone occupies a unique place in Falk’s performance art repertoire—it is the only piece that she has been able to observe as an audience member, as she does not perform in it. Graff, a professionally trained singer, is the central figure in the piece—the action includes his inching backwards across the stage, dressed in a tuxedo and singing “Allegro alla breve” from Igor Stravinsky’s Pulcinella, as people emerge from the audience, one by one, and begin to polish his shoes with rags. It was Graff who, in 1971–72, curated a seven-artist, fifty-two-venue cross-country performance art tour in which Falk participated. While the physical demands of that national tour ended Falk’s commitment to performance art and refocused her energies on producing art in her studio, her interest in collaboration persisted.

Klassen was a fellow teacher whom Falk met at summer school, which she attended to upgrade her qualifications, in Victoria in 1956. Although Klassen is not an artist, she has been integral to several of Falk’s works in a hands-on way and has shared a living space with Falk for much of the time since their first meeting—first in 1970–73, when Falk, Klassen, and Graff all shared a house; and then in the late 1980s, when after Klassen’s surgery for colon cancer left her cancer-free but with nerve damage and limited mobility in her right hand and arm, she moved in with Falk permanently.

In addition to contributing to the laborious group sewing project that Falk invoked in order to finish Beautiful British Columbia Multiple Purpose Thermal Blanket, 1979, for the lobby of the B.C. Central Credit Union in Vancouver, Klassen also participated in various performance art pieces and was part of the team that travelled to Ottawa with Falk to install Veneration of the White Collar Worker #1 and Veneration of the White Collar Worker #2, 1971–73. The two women share a home together, and Falk’s memoir, Apples, etc., is dedicated to Klassen.

Much of this collective activity can be understood in the traditional sense of an artist hiring studio assistants who also happen to be part of their circle of friends. However, through Falk’s involvement with Intermedia, she became engaged with the more process-driven collaborative practice that is now common in Vancouver and across Canada. She participated in many Intermedia projects, including the three exhibitions the group presented at the Vancouver Art Gallery between 1968 and 1970. In response to The Dome Show, their final exhibition there, Province writer James Barber noted, “Every day there has been some community involvement and despite the criticism of the gallery by the old guard, who claim that the Gallery is going to the dogs, that its approach to art, its involvement of art with the life process, caters only to a small minority. There are figures which prove them wrong.” Falk then was an early participant in the unresolvable struggle between avant-garde artists and museum traditionalists that is a mainstay to the cultural sector—in many places, yes, but also very much so in the city of Vancouver.

The Uncanny

“For me, art is totally a working out of personal images,” Falk has said. Inspired by her surroundings, her creations usually originate as visions in her imagination, which she then figures out how to make in real life. Often, the results contain elements of the absurd, surreal, or uncanny.

A concept described by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud in a 1919 essay as “that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar,” the uncanny was an experience that greatly interested the Surrealists. Perhaps the most iconic Surrealist work is Object, 1936, by Meret Oppenheim (1913–1985): a fur-lined teacup, saucer, and spoon that creates an unsettling effect by replacing the smooth, manufactured surfaces of porcelain and silverware with the mammalian cover of gazelle hide. Falk acknowledges this as a work that inspired her.

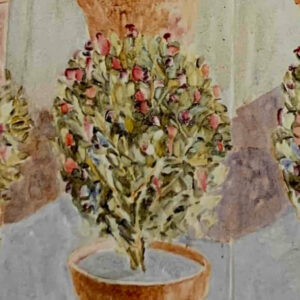

Falk’s inclination toward the uncanny was evident in her breakthrough installation Home Environment, 1968, made manifest through the combination of real household objects—painted pink—and elements rendered in clay. It also emerges in Falk’s performance work, such as Red Angel, 1972, in which lavish elements (a long white gown and feathered angel wings) are set against more homely ones (a wringer washer, record players, and slightly comical sculptural parrots). The uncanny is also at the foundation of the Theatre in B/W and Colour series, 1983–84, which is premised in the pairing of unexpected elements: rose trees and light bulbs, cabbages and ribbons, armchairs and rocks.

For her participation in the 1977 exhibition Four Places: Allan Detheridge, Gathie Falk, Liz Magor, An Whitlock at the Vancouver Art Gallery, Falk filled her estranged husband’s flame-painted 1936 Ford coupe with ceramic watermelons and exhibited it alongside works from her new ceramic series, Picnics, 1976–77.

As art critic Robin Laurence noted in a Vancouver Art Gallery publication from 2000: “Some of the objects in the picnics are the quintessence of ordinary: watermelons, lemons, green bottles, eggs, cakes. Some are oddly incongruous with the picnic theme: clocks, crowns, cabbages, high-heeled shoes, a stack of fat red, cartoon-style hearts. And some, in their unexpected juxtapositions, create a mood of gallows humour and death-in-life surreality: golf balls sprinkled like monstrous peppercorns on three dead fish; a black bird lying dead atop a red mantel clock; a grey dog like a tomb figure guarding an offertory pot of pink camellias; a teacup whose contents are engulfed in enormous flames.”

We can look to Falk’s history of group shows to find artists with whom she shares concerns, such as Liz Magor (b.1948), whose juxtaposition of incongruous objects, such as the cast mitten and real cigarettes of Humidor, 2004, or the cast rocks and real cheese puffs of Chee-to, 2000, have been placed alongside Falk’s works. A more direct connection can be found in the series Gathie’s Cupboard, 1988–98, by Jane Martin (b.1943), in which Martin used a precise drawing style and inclination toward depicting flesh to create paintings, drawings, and prints in ode to Falk.

Religious, Political, and Feminist Beliefs

With the emphasis Falk places on the ritual of daily life, and the recurrence of apples, eggs, fish, and other Christian symbology in her art, it is tempting to interpret a connection between her religion and her work. However, she has steered viewers away from this method of decoding.

In “Statements,” a text compiled from a series of interviews conducted by Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker with the artist in April 1985, Falk clarified her position: “I decided I would try to be a Christian, rather than try to paint illustrations of Christian teachings. If you have something serious to say, you should be clear about it; if you paint it, it’s not likely that you will be very clear. Something important should be said in words: you should write it or talk it. Better yet, you should live it.”

Falk’s spiritual principles are most evidently manifested in her work through her veneration of the everyday and her commitment to collaboration and community. There are a few moments in Falk’s artistic production when she incorporates overt political commentary—such as the “war game” analogy in Some Are Egger Than I, 1969, and the daily enumeration of warships in English Bay for her Hedge and Clouds series, 1989–90. But there always exists a connection to Falk’s day-to-day experience that allows these tough subjects to sit comfortably within the rest of her oeuvre.

There are some works that possess a subtler metaphorical hint at Falk’s underlying socio-political concerns. In the early performance Skipping Ropes, 1968, one of the participants says to the others, “These are your orders. When you hear the gong say your name, age, sex, and racial origin; I repeat, when you hear the gong say your name, age, sex, and racial origin.” Four years later, the words “name, age, sex, racial origin” would be chanted in a four-part fugue during a performance entitled Chorus, 1972.

In a conversation about Skipping Ropes in the 1982 Capilano Review, writer Ann Rosenberg suggests, “There are some political implications there,” and Falk responds, “Well, sure there are. In any of my pieces there can be undertones or overtones of various kinds. Political, what’s done to us, the orders we get, the forms we have to fill out, the information that has nothing to do with anything, things like that.” Rosenberg nudges Falk, saying, “But in a heavier sense, gas chambers…” and Falk replies, “Yes, also that.” In Apples, etc., Falk recalls her nightly childhood invocations, which included saying prayers for the Jewish people who were being persecuted in Nazi Germany and the Mennonites who were being kidnapped and murdered in Russia under Stalin.

Other works possess equally strong depictions of Falk’s lived experience and its expression in metaphor. In several of her sculptures from the series Picnics, 1976–77, ceramic flames are an inexplicable element of her alfresco “meals,” emerging from teacups, a birthday cake, and a pile of maple leaves. Falk ties the recurring flames back to a memorable anecdote a friend shared with her about a birthday cake catching fire. She also associates them with the childhood memory of helping her mother to burn off dead winter grass so that new grass would grow in its place, which could be seen as a symbol of purification and regeneration.

Falk’s ex-husband Dwight Swanson, who had caused her such pain in a short time, had driven a Ford coupe with flames painted on the doors; when he reoffended, the image of the flames was used as evidence against him in his trial, thus ending their marriage. Falk exhibited the coupe and the Picnics in Four Places: Allan Detheridge, Gathie Falk, Liz Magor, An Whitlock at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1977. It is difficult not to see the flames as representative of pain and destruction—the antithesis of the notions of purity and rebirth. Falk has maintained that she doesn’t intentionally insert messages in her work, although sometimes they emerge regardless.

-

Gathie Falk, Picnic with Birthday Cake and Blue Sky, 1976

Glazed ceramic with acrylic and varnish in painted plywood case, 63.6 x 63.4 x 59.7 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

-

Gathie Falk, Ford coupe and Picnics, 1976–77

Installation view, Four Places: Allan Detheridge, Gathie Falk, Liz Magor, An Whitlock, at the Vancouver Art Gallery, 1977

Photograph by Joe Gould

Falk seems to have held a similar opinion about where her feminist ideals belonged. In the fall of 1984, Nicholas Tuele, curator at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria at the time, interviewed Falk while he was preparing the exhibition British Columbia Women Artists, 1885–1985. He posed a question about whether she felt she faced particular concerns as a woman artist. Falk responded that she “didn’t have any more concerns about that than [she] did about other things in life” and acknowledged that in her art career, she had had many opportunities. She went on to note that she was “a feminist from the word go, even when there was no such word.“ From a young age she recognized that the world treated women unfairly—it was she rather than her brothers who bore the brunt of caring for their mother. Although she did not adhere herself to the term, Falk acknowledged that of course she shared feminist concerns about women’s rights and freedoms.

Just as Falk’s imagery and ideas are not wholly free of Christian inflection, given how much her work is inspired by pictures that come to her in her mind’s eye, so too does a feminist life inevitably affect her art. The incorporation of craft processes such as ceramic or the papier mâché of the Dresses series, 1997–98, and The Problem with Wedding Veils, 2010–11, into the language of fine art; the recurring images of domestic items, like furniture, table settings, and clothing; and the inclination toward depicting nature—not an epic or sublime kind of nature, but fruit, flowers, water, and skies—can all be seen as feminist artistic strategies.

Whether it is consciously evoked or not, Falk’s work is infused with many of the strategies used in feminist art to challenge patriarchal assumptions about what deserves to be included in the realm of high art. Falk, like artists such as Joyce Wieland (1930–1998), Betty Goodwin (1923–2008), and Irene Whittome (b.1942), chose images and processes that allowed her to explore the personal, along with other gender issues. As such, Falk and her peers broadened the definition, scope, and potential of art in this country, setting the stage for many subsequent generations of feminist and otherwise politically driven artists.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements