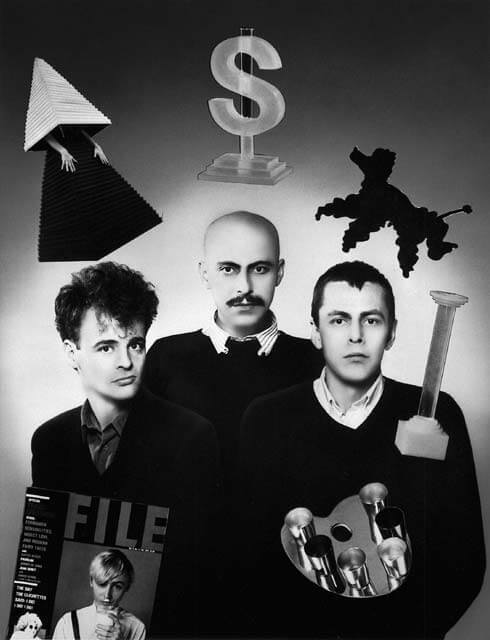

Provocateurs General Idea (active 1969–1994) invented their history and made it reality: “We wanted to be famous, glamourous and rich. That is to say we wanted to be artists and we knew that if we were famous and glamourous we could say we were artists and we would be.… We did and we are. We are famous, glamourous artists.” The group—comprised of AA Bronson, Felix Partz, and Jorge Zontal—met in Toronto in the late 1960s and went on to live and work together for twenty-five years. General Idea ceased activities in 1994, with the untimely deaths of Partz and Zontal from AIDS-related causes.

Before General Idea

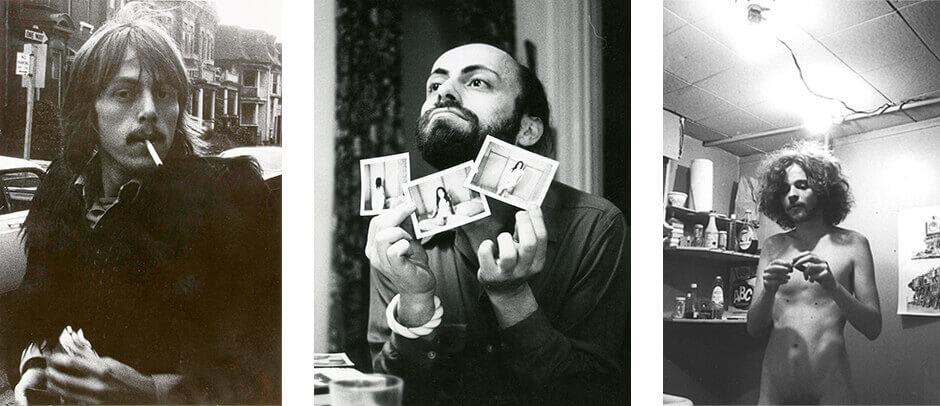

The three individuals who became General Idea were Ronald Gabe (1945–1994), Slobodan Saia-Levy (1944–1994), and Michael Tims (b. 1946). They met in Toronto in 1969, drawn to the city’s blossoming countercultural scene, and later took the names Felix Partz, Jorge Zontal, and AA Bronson, respectively. General Idea started as an anonymous group before crystallizing into an intentional three-part group.

Gabe (Felix Partz) was raised in Winnipeg, Manitoba. He studied at the University of Manitoba School of Art. In an episode that prefigures General Idea’s early work in the 1970s, in 1967 Gabe made photocopies of famous works by artists for a printmaking class, including pieces by Andy Warhol (1928–1987), Frank Stella (b. 1936), Nicholas Krushenick (1929–1999), Richard Smith (b. 1931), and Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997). He playfully titled this conceptual project Some Art That I Like. In 1968 Gabe travelled to Europe and Tangiers. Upon his return to Winnipeg, he created a series of ziggurat paintings, which were inspired by Islamic patterns he had viewed on his travels. General Idea later used ziggurat imagery in their work. In 1969 Gabe travelled to Toronto to visit his friend Mimi Paige at Rochdale College—ultimately, he remained in the city and made it his home.

Saia-Levy (Jorge Zontal) was born to Yugoslavian-Jewish parents in a concentration camp in Parma, Italy, just as the Second World War was ending. After living in Switzerland, Yugoslavia, and Israel, Saia-Levy and his family were eventually accepted as immigrants in Venezuela and settled in Caracas. He moved to Halifax, Nova Scotia, in the 1960s to study architecture at Dalhousie University. He also studied film and theatre, travelling to New York City on a regular basis to pursue acting lessons. In the late 1960s Saia-Levy studied video at Simon Fraser University (SFU) in Vancouver and took performance classes with dancer Deborah Hay (b. 1941) at Intermedia. This travel to Vancouver was significant, as it led to Saia-Levy’s first meeting with Tims, who was there teaching a workshop at SFU. In 1968 Saia-Levy left Halifax with the intention of moving to Vancouver for good. Like Gabe, his stay in Toronto became permanent. It was at Theatre Passe Muraille in Toronto where Saia-Levy met Tims again and was introduced to Gabe.

Tims (AA Bronson) was born in Vancouver in 1946 to a military family, living in cities across Canada. He moved to Winnipeg in 1964 to study architecture at the University of Manitoba. It was at university where Tims met Gabe, through their mutual friend Paige. In 1967, before completing his degree, Tims and several classmates dropped out to form an alternative community comprised of a free school, commune, free store, and newspaper. The newspaper was called The Loving Couch Press and Tims served as a contributing editor. During this period Tims also worked as a volunteer apprentice for a therapist specializing in intentional communities. Through this work he travelled across Canada, which led to Tims meeting Saia-Levy in Vancouver and also put the work of Intermedia on his radar. Tims became interested in exploring other communes, travelling to Montreal and Toronto. In Toronto he settled at Rochdale College, where he quickly became involved in Coach House Press and Theatre Passe Muraille.

The three artists’ experiences in architecture, theatre, film, art, intentional community, Gestalt therapy, and independent publishing informed their later work as General Idea. The group, according to Bronson, was born out of the “late Sixties psychedelia of student revolution, fluorescent posters, underground newspapers and Marshall McLuhan, and inspired by Canada’s first artist-run centre … Intermedia.”

Becoming a Group

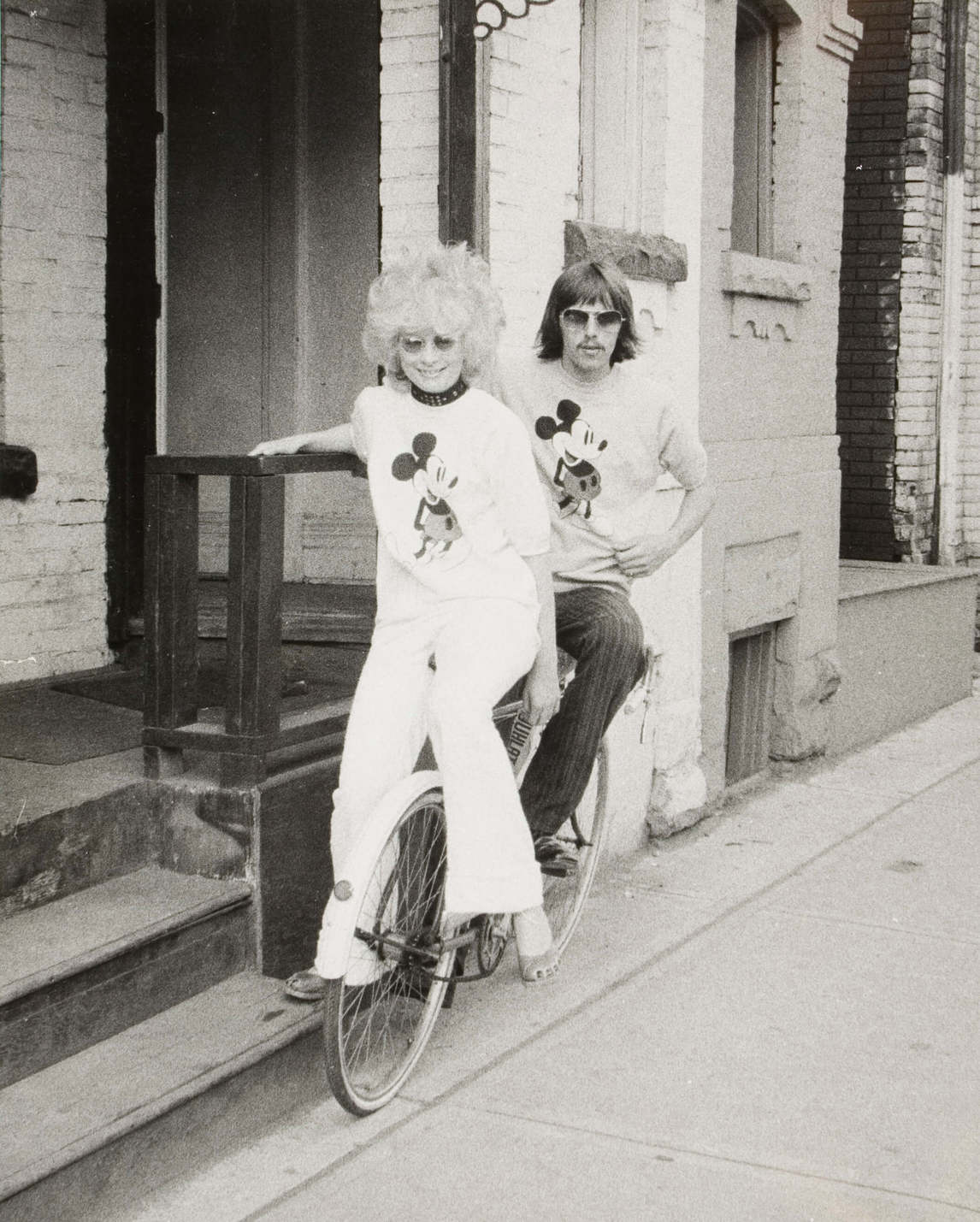

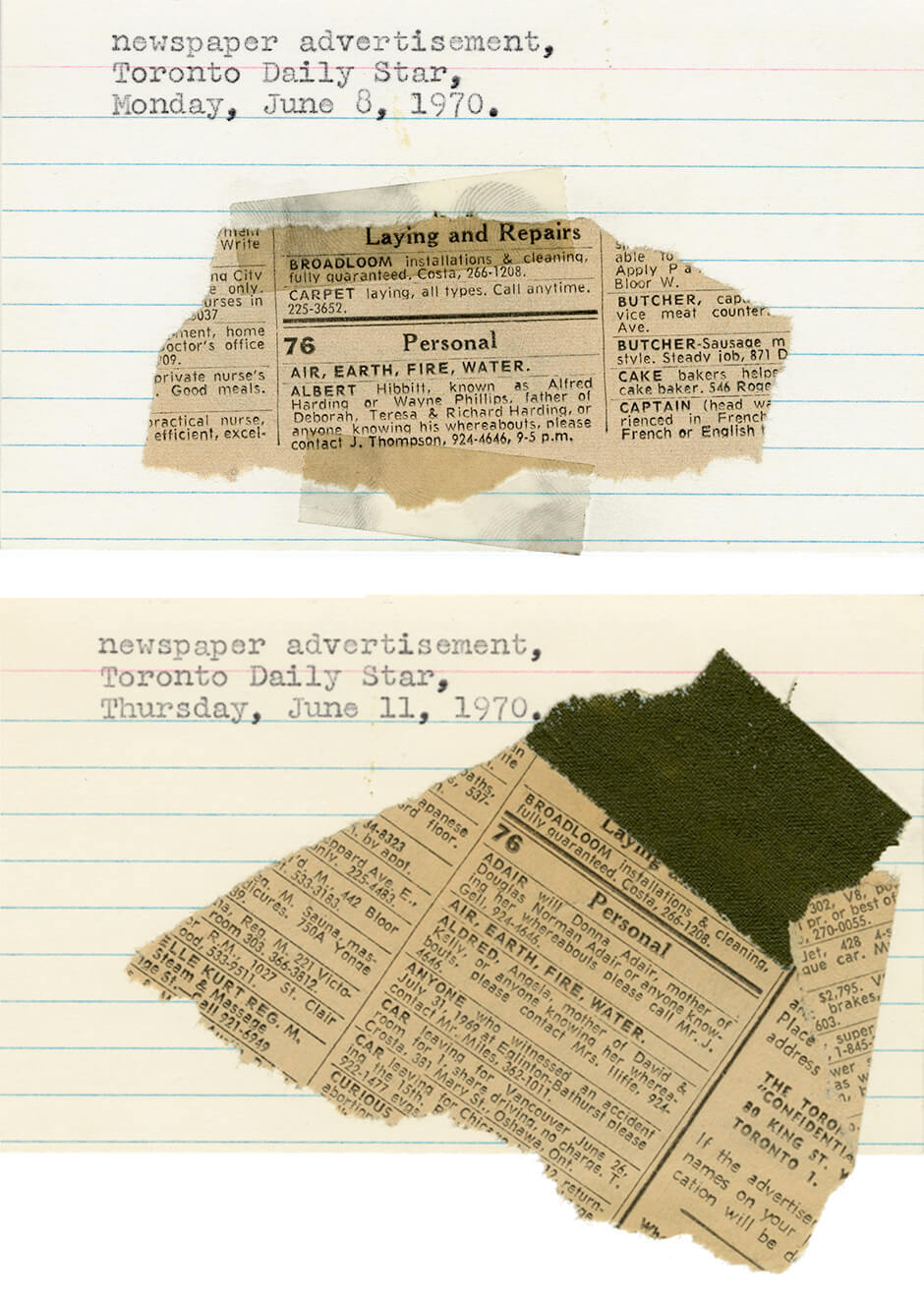

By 1969 Ronald Gabe, Slobodan Saia-Levy, and Michael Tims were all in Toronto and came into contact at Theatre Passe Muraille during rehearsals for the production Home Free. The theatre, founded out of Rochdale College—an experimental free university in Toronto—offered a countercultural scene that attracted many visual artists. As Bronson noted, “The counterculture scene was small at that time. The three major nodes were Rochdale College, Theatre Passe Muraille, and the Coach House Press.”

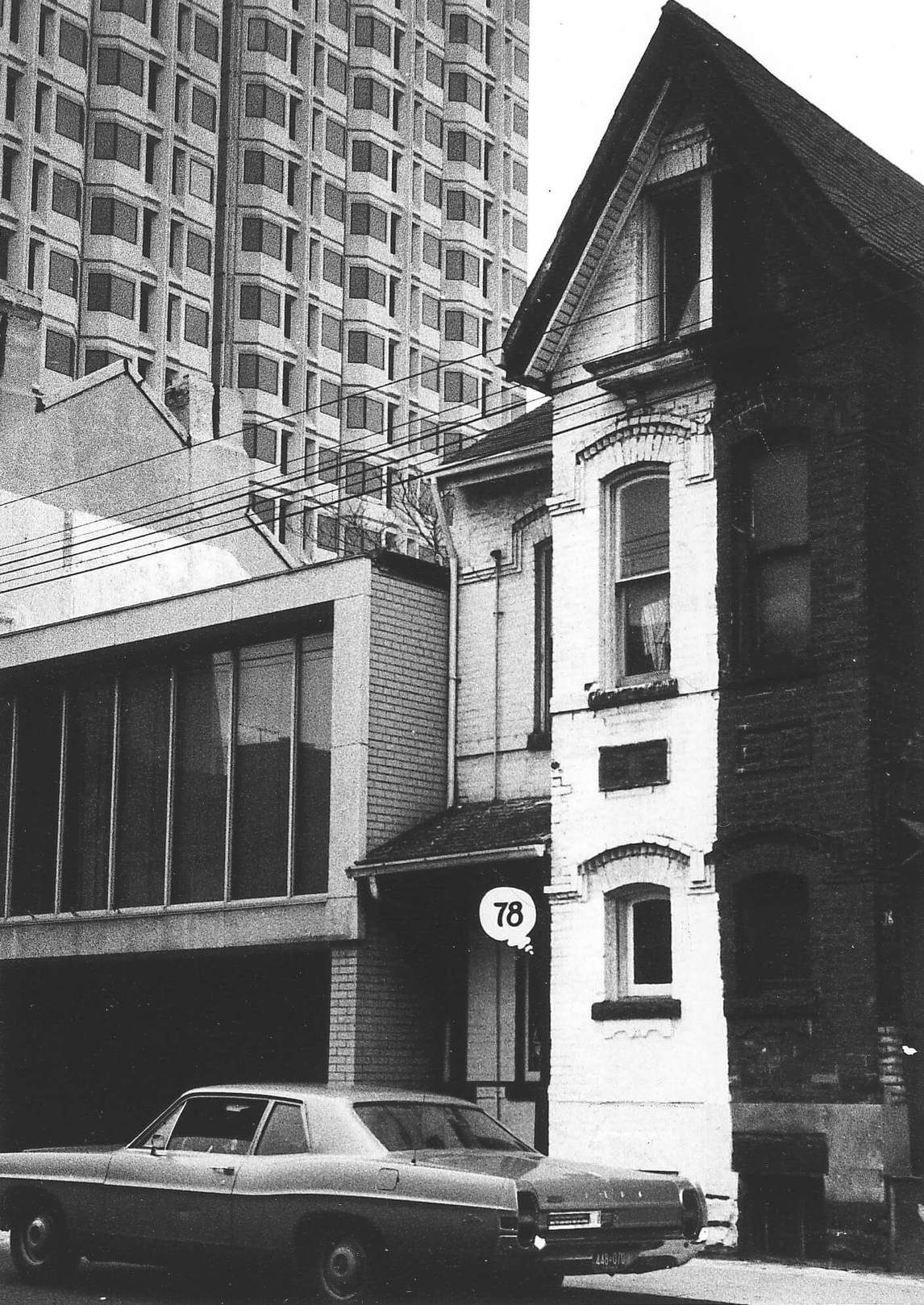

Shortly after meeting, the three moved to a house at 78 Gerrard Street West in downtown Toronto along with Mimi Paige (Gabe’s then-girlfriend) and Daniel Freedman (a friend and actor). Bronson recalls that the members of the household were unemployed and amused themselves by creating fake window displays in the house, a former store.

One project—targeting a nearby nurses’ residence—involved a display of romance novels about nurses. This gave the impression that the house was a bookstore, but prospective customers were prevented from visiting by a sign on the door that indicated the shopkeeper would return in five minutes. Significantly, the group didn’t see these early experiments as artwork.

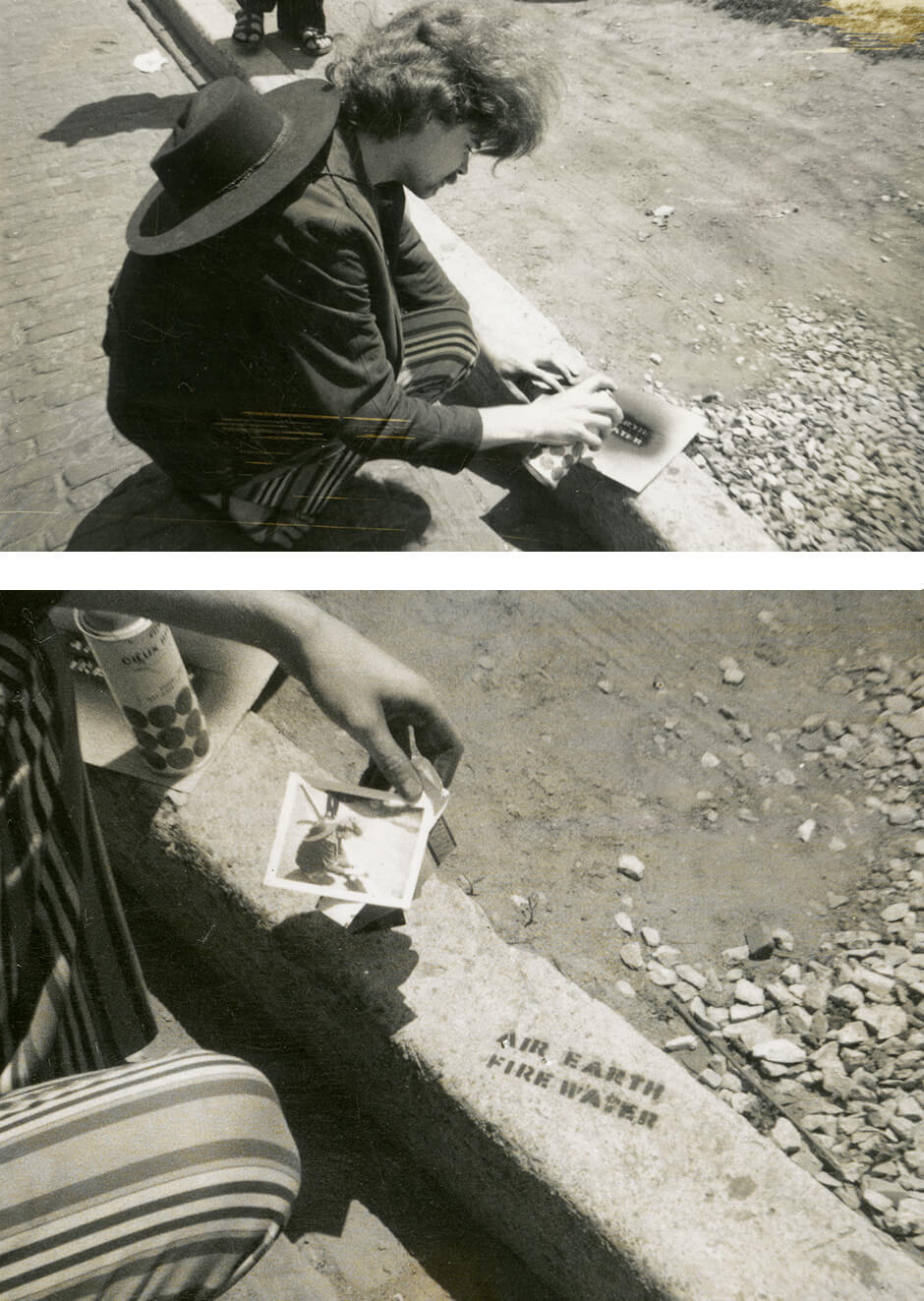

Subsequent installations were larger and more intricate, as well as open to the public, such as the in-house group show Waste Age, 1969, which featured works by Saia-Levy, Gabe, and Tims, as well as Mary Gardner. Many early projects by the group were executed in ephemeral media, such as mail art, performance, photography, and film. Members of the house also took part in collaborations while creating individual projects in this period. For example, Gabe exhibited paintings and Saia-Levy exhibited photography, and Tims travelled to Vancouver to participate in an experimental performance.

In 1970 General Idea participated in their first group exhibition, Concept 70, at A Space (which was in the midst of transitioning from being Nightingale Gallery) in Toronto. The group intended to show a work called General Idea. Bronson recounted that their name emerged as a result of a miscommunication, whereby the gallery listed the artists as General Idea. “General Idea was the name of one of the first projects we presented,” he stated, “…but everyone misunderstood and thought it was the name of the group.” They decided to keep it. The name initially had no specific meaning, though it evoked the military and corporations such as General Electric. Bronson jokingly explained that it referred to the “general idea” of what the group did and noted that the corporate reference was “radically politically incorrect at the time.” The name also helped to obscure discrete identities within the group, challenging the myth of the individual artist as genius.

Noting the casual nature of the group, Bronson later explained, “We were just a group of people having a good time.… We went everywhere together, parties, we always showed up together.” They presented themselves theatrically: they would take special care to stage their entrance to events, arriving at gallery receptions with an entourage.

Establishing a Tripartite Identity

During the early 1970s, Ronald Gabe, Slobodan Saia-Levy, and Michael Tims assumed pseudonyms. This was a popular practice for artists involved in mail art networks. Initially, Gabe used the names Felicks Partz and Private Partz, before settling on the cheeky name Felix Partz. Saia-Levy’s name, Jorge Zontal (pronounced “Hori-zontal”), came from a song on an old record. Tims’s AA Bronson derived from a pen name created by the publisher of Bronson’s pornographic book, Lena, a novel he had written in collaboration with Susan Harrison. Tims’s pseudonym was A.L. Bronson, but friends misremembered it as A.A. Bronson (the punctuation was later dropped).

In 1970 General Idea moved to 87 Yonge Street, to a loft located above the Mi-House restaurant in the heart of Toronto’s Financial District. The membership of General Idea in the early 1970s was intentionally amorphous. Partz noted that in the early days, “We purposely obscured actually, who General Idea was, because we were involved with working and living with a variety of people.… Everybody was seen as General Idea.”

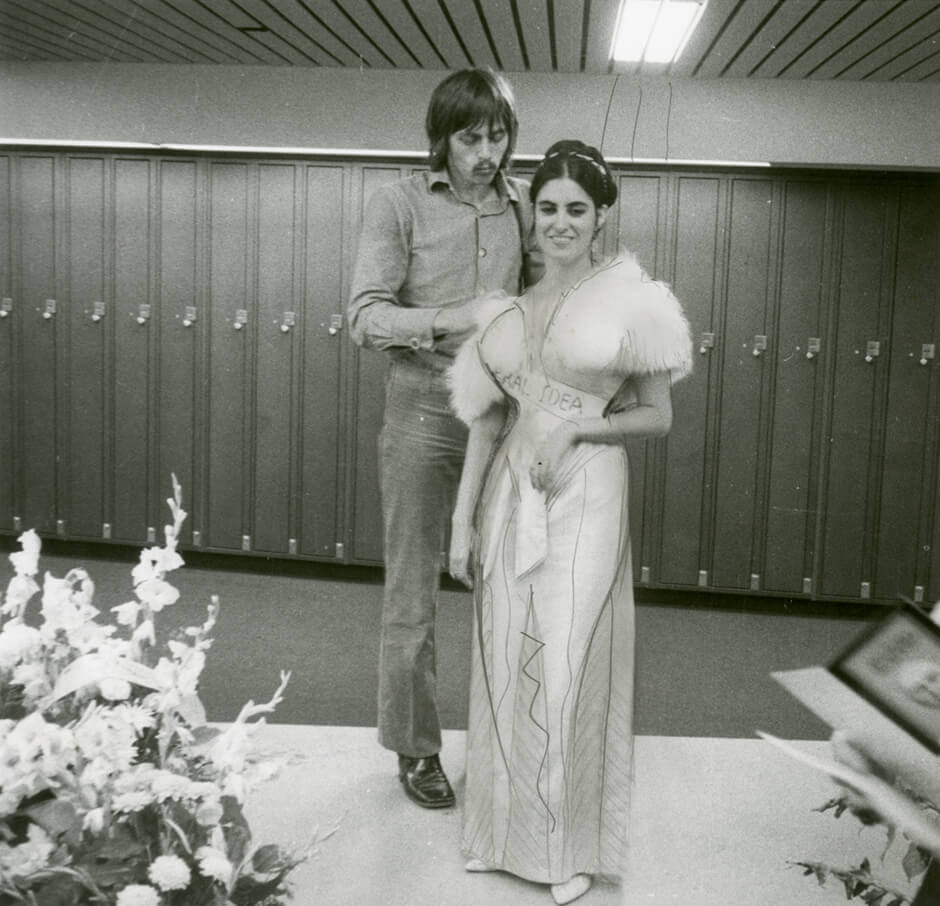

At this time General Idea created some work using the beauty-pageant format and the figure of Miss General Idea emerged as a muse for the group. Of the pageant, Partz explained, “It was our examination of the existing art world … a questioning of the process by which masterpieces are created … validated … selected and worshipped.” The 1970 Miss General Idea Pageant, 1970, was staged as part of their multimedia event What Happened, 1970, in the Festival of Underground Theatre at the St. Lawrence Centre for the Arts and the Global Village Theatre. The group continued with this format for The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant, 1971, an elaborate project that culminated in a performance in Walker Court at the Art Gallery of Ontario. The pageants speak to the group’s early interest in employing satirical mimicry of popular forms as a means of social critique. As curator Frédéric Bonnet noted, the group understood that the artist “was no longer someone who made things to hang on walls, but a commentator on society.”

In 1972 General Idea had their first exhibition at a commercial gallery: Carmen Lamanna Gallery in Toronto. This marked the beginning of the group’s relationship with gallerist Carmen Lamanna, an individual who had a significant impact on their oeuvre. That same year, when they were in their mid-twenties, Partz, Zontal, and Bronson made a commitment to live and work together until 1984. This solidified the group’s tripartite structure: as Partz explained, “It became quite clear, that Jorge, AA and myself were the actual ongoing core members of General Idea, and the ones that were most involved.”

By this point the trio had established a domestic relationship, and their art production was a part of their lives together. Bronson described the significance of selecting the year 1984: “We thought of that as a kind of Orwellian symbol of the future, and I think that date kept us together: we could always say, well, it’s only seven more years, or, well, it’s only four more years, and so on, until our living and working together had become so habitual that we didn’t know how to do anything else. We were addicted to the intensity of our own total living/working relationship.” In the mid-1970s the artists began to clarify their identity, in contrast to the previous ambiguity of the group’s membership. Partz described their aim as akin to an advertising campaign: “to define who General Idea was, visually.” This can be seen in Showcard Series, 1975–79, and Pilot, 1977.

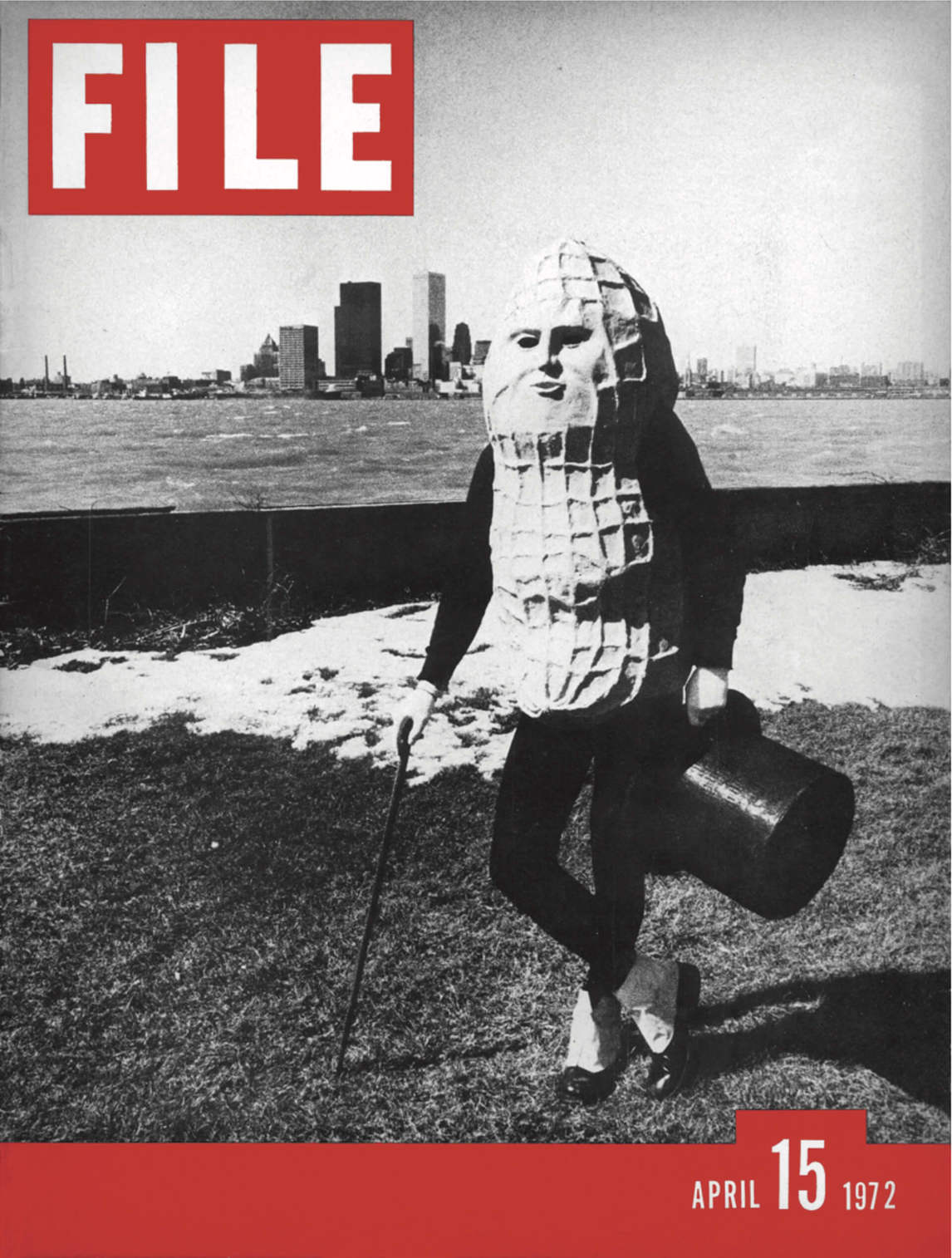

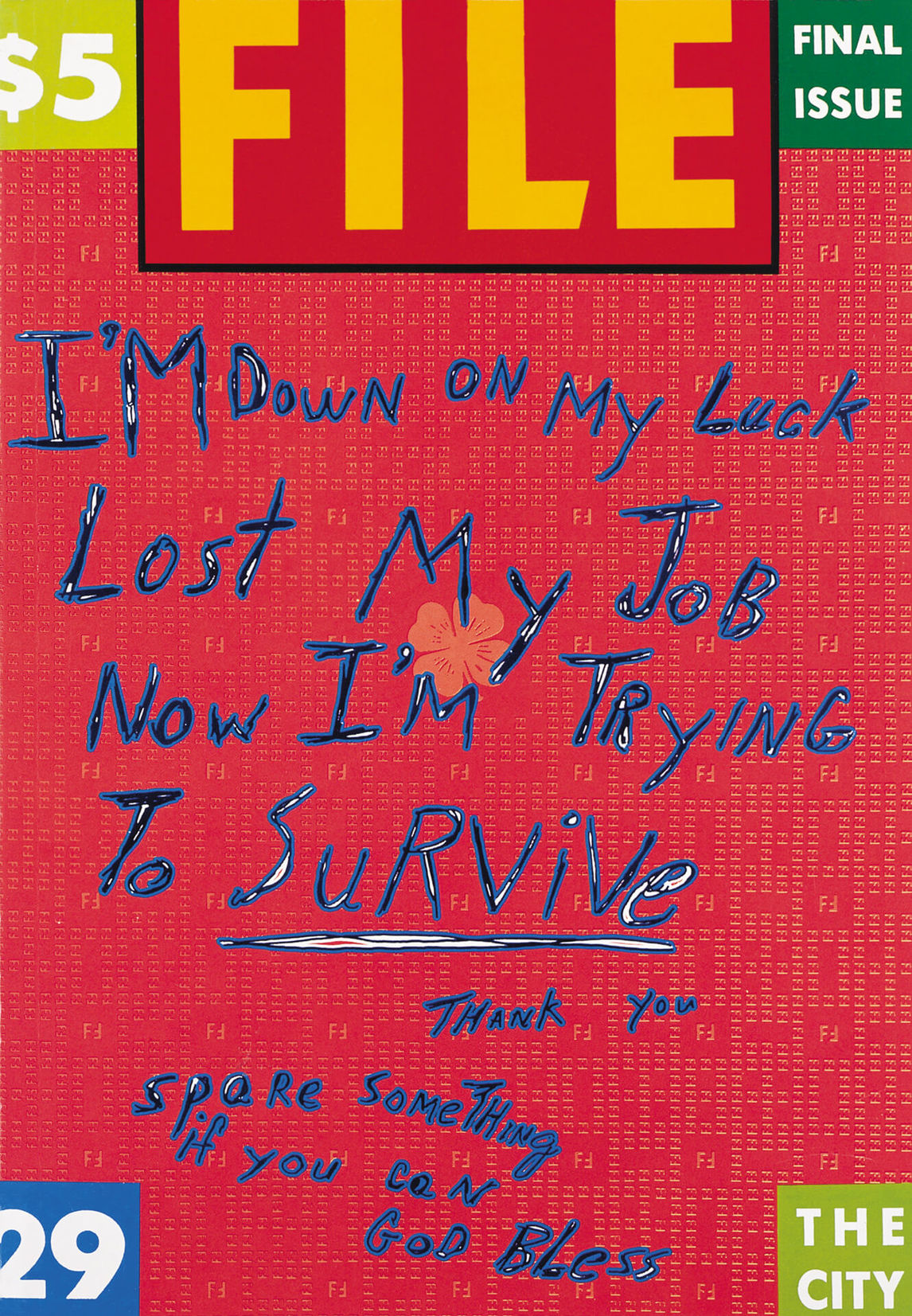

During the early 1970s General Idea founded two key institutions. The group expressed their interest in the appropriation of media formats in establishing FILE Megazine. Launched in 1972, the publication adopted the logo of the popular American news magazine LIFE. General Idea designed FILE to be a “parasite within the magazine distribution system.” As Bronson explained, “We knew that if it looked familiar, people would pick it up, and they did. We thought of it as a kind of virus within the communication systems, a concept that William Burroughs had written about in the early ’60s.”

The second institution was Art Metropole. By fall 1973, Partz, Zontal, and Bronson had moved the General Idea studio to the third floor of 241 Yonge Street, and they established Art Metropole in the front of the space. Art Metropole was a distribution centre and archive, which held various low-cost formats, including artists books, video and audio works as well as multiples. The aim of the institution was to create an alternative distribution system for art. Still operating today, Art Metropole holds an important place in the history of alternative arts venues in Canada.

After the Pavillion

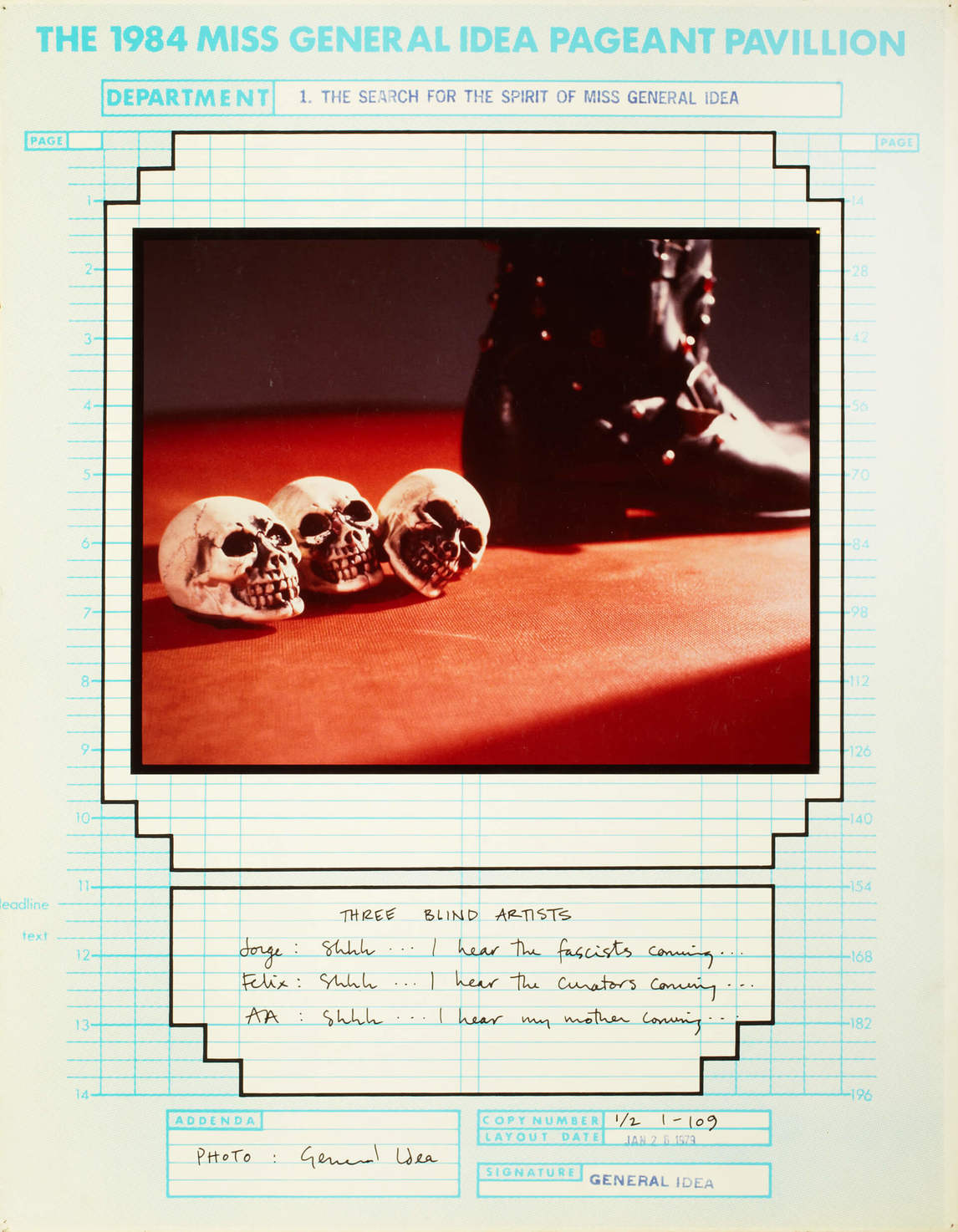

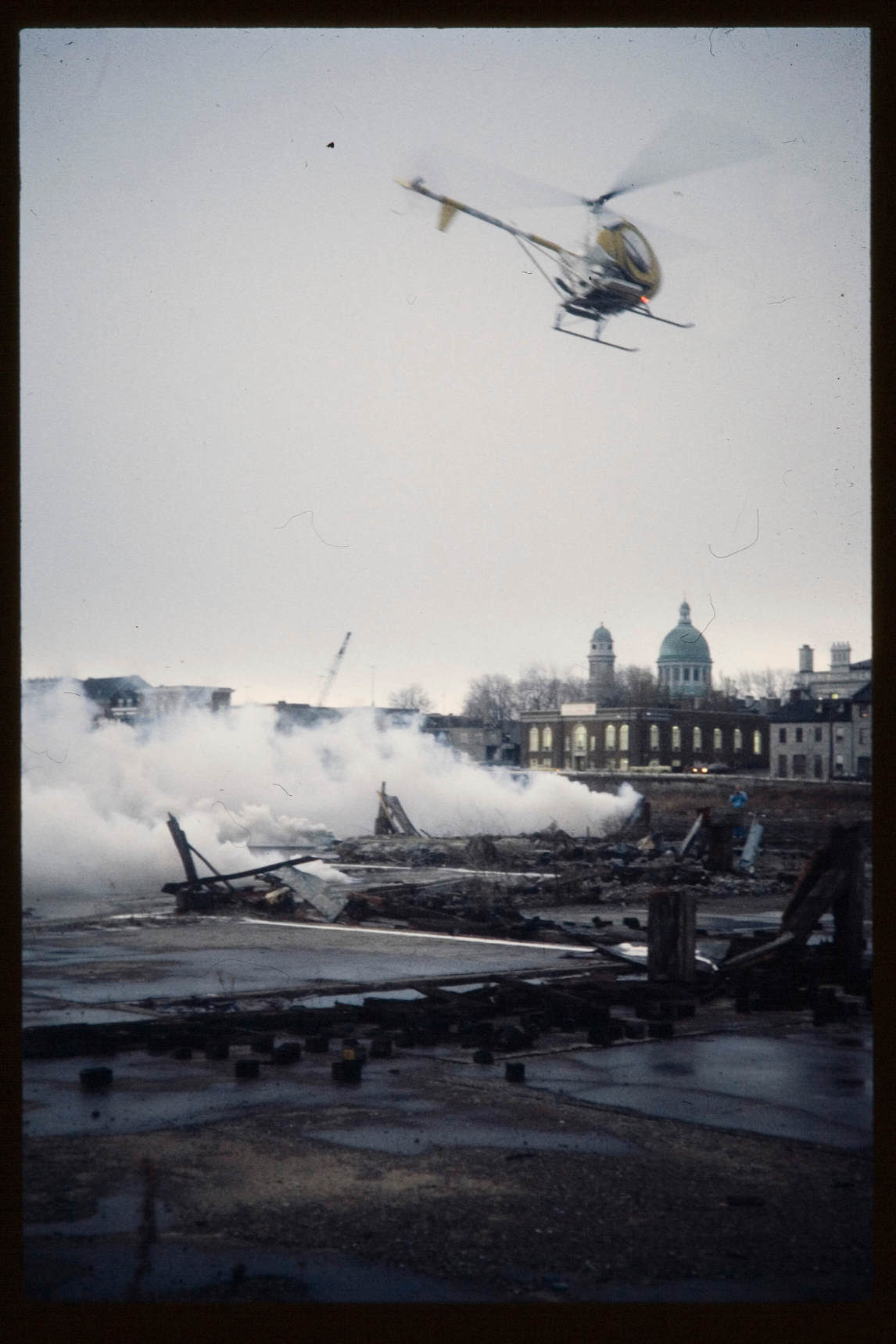

General Idea began exhibiting in European galleries in 1976 and had a vigorous European exhibition history from then on. For the next decade, as AA Bronson explains, “this was the focus of our life together.” In 1977 the group moved to a large studio space on Simcoe Street. At this time General Idea shifted the approach to their pageant concept, taking on the role of fictional archeologists. This move was tied to the reputed destruction of the notional 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion, which they reported to have been engulfed in flames during the Miss General Idea Pageant in 1984. The artists had announced and begun staging elements of this faux destruction in 1977, documentation of which was used in exhibitions and videos from that year on.

For instance, their video Hot Property, 1977–80, includes footage from this fictitious disaster. Its voiceover notes that the facts surrounding this event were very much obscured: “But what actually happened, why did the Miss General Idea 1984 Pavillion burst to flames and burn to the ground? Was it a spontaneous reaction of the audience? Was it critical arson? Or was General Idea always planning to pull the rug out before the climax? So many unanswered questions, so many loose ends, so many ambiguities and so many clues.” In subsequent exhibitions, General Idea presented the alleged ruins of and artifacts from the Pavillion. The creation of relics and ephemera from the various rooms of the Pavillion provided a means for General Idea to expand on different aspects of the structure using multiple media, as well as allowing the group to continue to engage in the concept of the pageant in new ways.

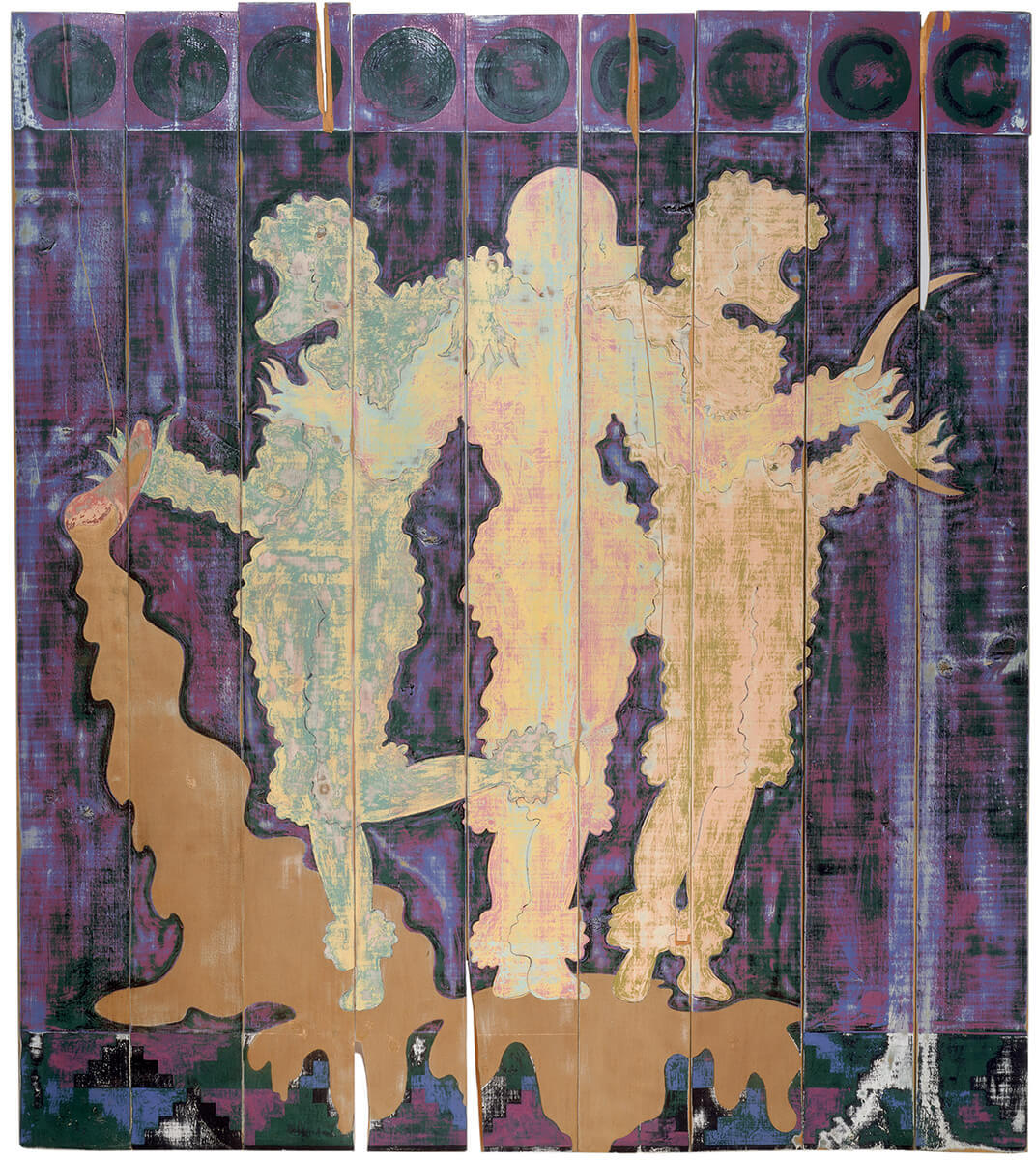

The figure of Miss General Idea also began to disappear from the group’s work in the late 1970s. New imagery emerged, such as the poodle, which was employed in several works. For instance, the dogs were first featured as architectural remnants from the ruins of the Pavillion in 1981. The trio also appeared as these animals in the portrait P is for Poodle, 1983/89, which was originally made for the cover of FILE. Other works included the large-scale paintings Mondo Cane Kama Sutra, 1984, which depicted fornicating dayglo poodles. As symbolic representations of the artists, this trope was a coded means for the artists to address their queer identity and to push art critics to address sexuality in their work.

General Idea received their first solo museum exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1979. The exhibition featured work produced during a residency, which was organized in collaboration with de Appel, Amsterdam. De Appel commissioned a made-for-television artwork and the exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum included the video Test Tube, 1979.

This attention in Europe was a significant achievement; AA Bronson noted that Switzerland, Austria, and Italy were particularly receptive to General Idea’s work at this time. Key exhibitions in the early 1980s included the Venice Biennale in 1980, where General Idea was part of the group exhibition Canada Video. In Venice they presented Pilot, 1977, and Test Tube, 1979. In 1982 they presented Cornucopia, 1982, as well as an installation that included painted constructions and works on paper, at the important exhibition Documenta 7 in Kassel, Germany. That same year, they presented work in photography and performance at the Biennale of Sydney.

“Because we were so ironic,” Bronson stated, “in Canada we were seen as not being really serious. Also, people would tell us that you can’t be a group and be an artist, artists don’t work in groups. But when we went to Europe … we were very quickly picked up and written about in political terms, Marxist terms, because we operated as a group, because we operated by consensus, because of the critical intent inherent in the work, and I think to a certain extent because of the sexual aspect: that we were, if not clearly gay, at least sexually ambiguous.” The international critical reception of General Idea’s work influenced how the group understood their practice and also filtered back to North American audiences.

In 1984 the group received recognition in the form of a large, touring retrospective titled The 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion. Bronson notes that this show was extremely important in terms of General Idea’s career as it was initiated by two of the most-influential museums in the period: the Kunsthalle Basel and the Van Abbemuseum Eindhoven. The European retrospective allowed the artists to reflect on their past production and rethink their future. The group identified this moment—the symbolism of the year 1984 and their increased recognition—as a new era in their practice. “We had made that commitment to work together ’til 1984,” explained Felix Partz. “So here was 1984…. We were involved in this retrospective, but also we were involved with this conclusion of a project. Or was it?” At this point General Idea had not yet received any recognition in the United States. Bronson also explains that though they were not taken seriously in Canada, they exhibited their work at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1984.

In 1985 General Idea was drawn to New York City. Bronson noted the significance of displaying their work in 1986 at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York, and of representation by New York City gallery International With Monument. The group recognized New York as a key site for the circulation of artists and curators from Europe. They rented an apartment at 120 West 12th Street in 1986, eventually adding a studio in the meat-packing district. Zontal spent more of his time in New York, while Partz remained based in Toronto, and Bronson travelled between them.

To keep their collaboration going, they communicated through telephone calls, faxes, frequent visits, and exhibition travel. As they had many international projects in the seven years that followed, they spent much of their year together on the road. Discussing their ability to work together despite geographical distance, they affirmed that over the years General Idea had developed its own language and a group mind.

AIDS Projects

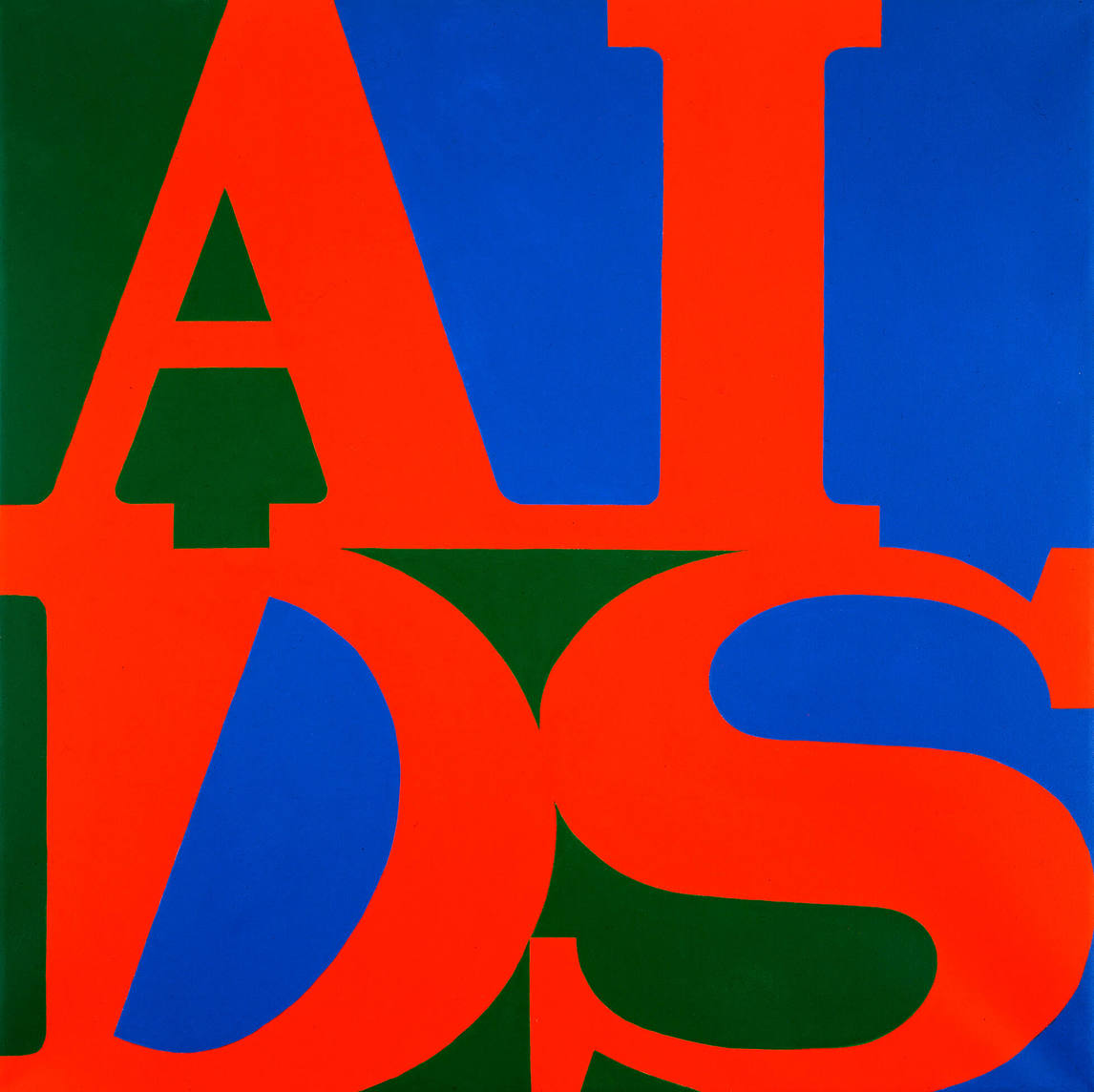

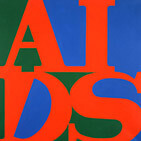

In 1987 the artists were invited by their gallery Koury Wingate in New York (previously International With Monument) to contribute to a June exhibition in support of the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR). General Idea created a painting, AIDS, 1987, that mimicked Robert Indiana’s (b. 1928) famous painting LOVE, 1966, but replaced the word “LOVE” with “AIDS.” From this moment on, the majority of General Idea’s work focused on addressing HIV/AIDS in ways both explicit and implicit.

The AIDS logo was central to many of these works, the bulk of which were temporary public art projects, as well as art created for display in museums and commercial galleries. For example, the group created an extensive series of posters, painting installations, a sculpture, and an animation for the Spectacolor Board in Times Square, New York City, all of which were based on the AIDS logo. The group’s aim was to use AIDS as a means to name what, at the time, was unnamable: raising AIDS as a topic of discussion in the public sphere.

General Idea’s works took a brazen approach to AIDS. In the late 1980s AIDS was a taboo topic and a climate of fear surrounded the disease due to widespread and extreme homophobia. This was because initially the disease was thought to exclusively affect gay men. For instance, in 1981 the first article in the New York Times to address AIDS identified it as a cancer that only affected homosexuals. This was not helped by the fact that inaccurate and inflammatory information about the disease circulated widely in the media. Many aspects of the AIDS pandemic, including its scope and severity, were not at first understood. Tremendous prejudice—including within the medical community—was widespread given the initial impact of AIDS in the gay community and its sexual transmission. As such, there was a moral dimension to the AIDS pandemic that activists, as well as artists, sought to address.

In 1989 General Idea produced the last issue of FILE Megazine, closing the publication after twenty-six issues over seventeen years. This was the start of a productive but difficult period for the artists. Felix Partz was diagnosed HIV-positive in 1989; Jorge Zontal was diagnosed the following year. The artists publicly disclosed their HIV status—Zontal addressed his illness in a 1993 interview on CBC Radio. Such public disclosure was significant given the politics of the era and the stigma associated with the disease.

Partz and Zontal’s diagnoses gave a new urgency to General Idea’s projects. A key exhibition in the 1990s was the touring retrospective General Idea’s Fin de siècle, which focused on the group’s works since 1984, primarily AIDS-related projects. Initiated by the Württembergischer Kunstverein in Stuttgart, Germany, this show toured in Barcelona and Hamburg in Europe and in Columbus, San Francisco, and Toronto in North America in 1992 and 1993.

Final Months

Zontal’s illness manifested in summer 1993, leading to a rapid deterioration that eventually left him blind and bedridden; in Partz the disease progressed more slowly. Bronson and Zontal left New York City and returned to Toronto. The trio again lived together under one roof, moving into a penthouse apartment in The Colonnade at 131 Bloor Street West.

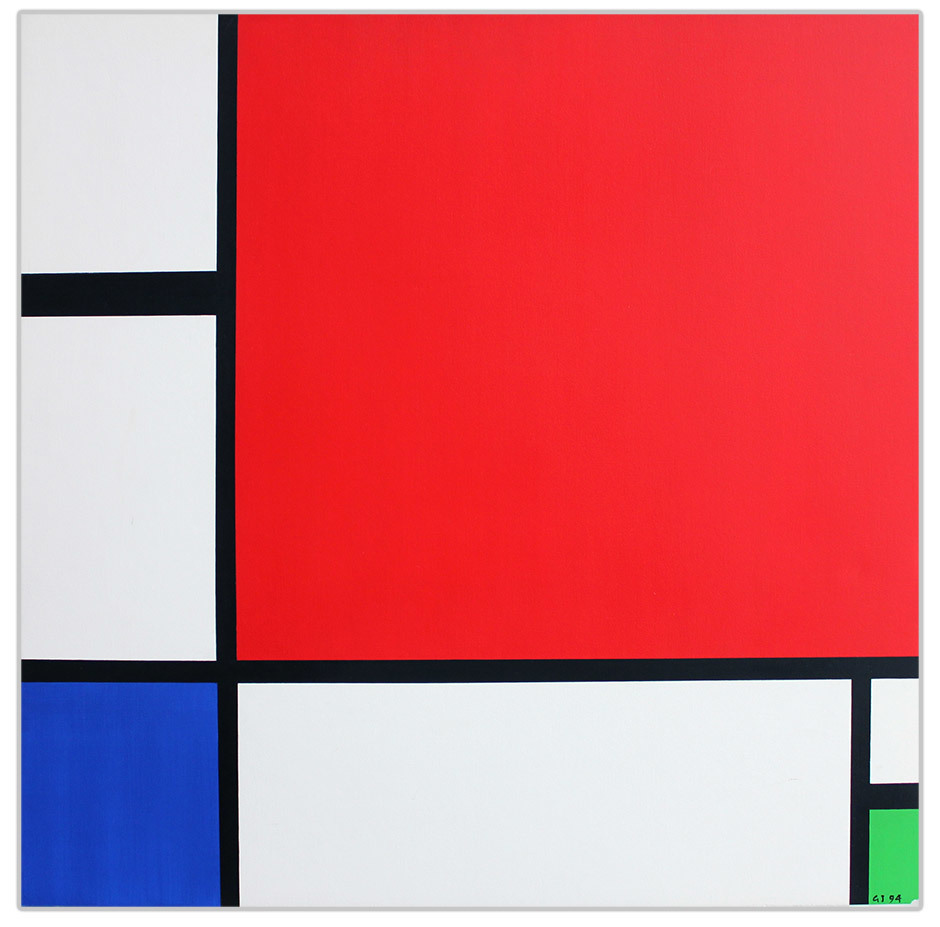

The Colonnade space was enormous, accommodating their studio practice—which continued unabated—as well as medical equipment. Together with a group of close friends, Bronson took on the role of caretaker for Partz and Zontal, who both decided they would endure AIDS, which at the time was a terminal illness, at home. In their last months together, the three worked on smaller projects. These included paintings, such as the Infe©ted Mondrian series, 1994, which appropriates and subverts the sparse linear aesthetic of the signature abstract works by Dutch painter Piet Mondrian (1872–1944). In the early 1990s General Idea received several significant honours, including the City of Toronto’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 1993.

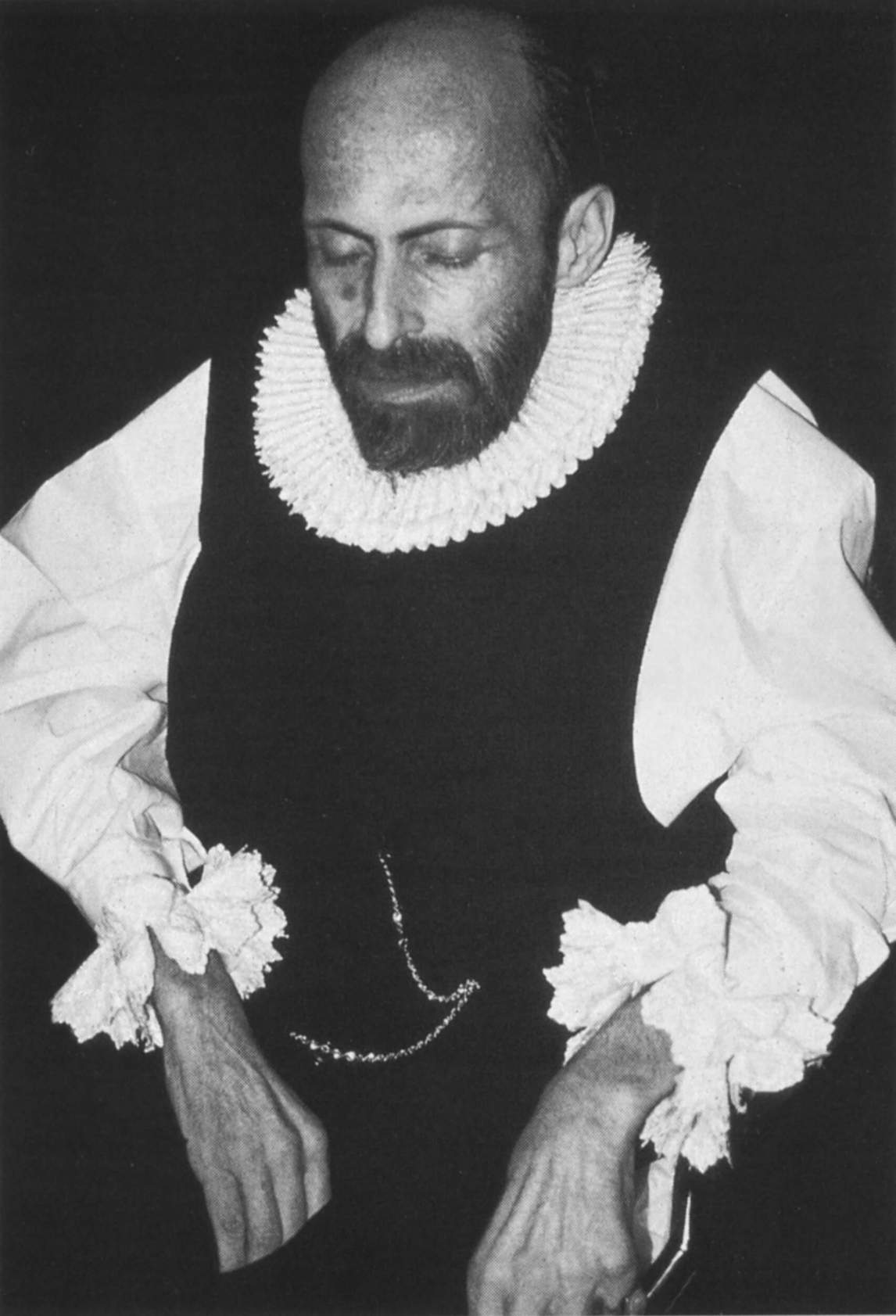

The group lived full lives despite the toll of AIDS. On January 29, 1994, General Idea honoured Zontal during his last days by celebrating his fiftieth birthday with a party at the General Idea penthouse. More than one hundred guests came to the event, some flying in from as far away as Los Angeles, New York City, Zurich, London, and Amsterdam. At the party Zontal made a spirited final appearance dressed at his request as a Spanish nobleman, a reference to the El Greco (c. 1541–1614) painting The Nobleman with his Hand on his Chest, 1580.

For the last two months of his life, Zontal was confined to his bed. He died of AIDS-related causes on February 3, 1994. Partz passed away four months and two days later, on June 5, 1994. Later that year General Idea was recognized with the Jean A. Chalmers Award for Visual Arts in Toronto. Bronson showed up to accept the honour in Partz’s wheelchair, wearing the white shirt with ruff donned by Zontal on his fiftieth birthday.

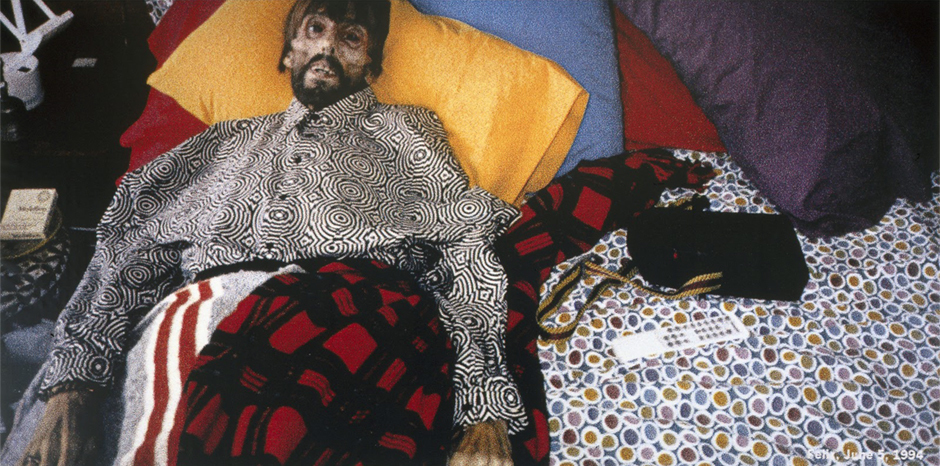

Reflecting in 2012, Bronson explained that he initially did not know how to be an artist outside of the group. Some of his early solo works were tributes to General Idea. The best known of these is the portrait of Partz, Felix, June 5, 1994, 1994, a billboard-scale digital print of lacquer on vinyl. This image features Partz at home in his bed in the hours following his death.

Felix shows Partz as he was in the last three weeks of his life. It is at once striking and unsettling. Surrounded by his favourite objects—including a tape recorder, a remote control, and a package of cigarettes—Partz is dressed in a vividly patterned black and white shirt, and his head rests against an array of multicoloured cushions. Bronson notes that Partz was drawn to vibrant clothing during his illness: “As [Felix] got closer and closer to death he started wearing colours that were more alive, brighter and brighter colours. He got totally crazed with colour and pattern.” Partz’s face, with sunken eye sockets and prominent cheekbones, betrays the trauma of AIDS; he suffered from wasting so extreme that his eyes could not close. Felix is a poignant tribute to Partz: a means of farewell and a testament to Bronson’s continued art making.

The demand for General Idea’s work has increased since the group’s demise. It circulates internationally and continues to receive recognition in the twenty-first century. For instance, in 2011 a travelling retrospective was organized by the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris and another retrospective will tour Latin America in 2016–17. This latter show is linked to the publication of General Idea’s catalogue raisonné. The group has also had significant exhibitions in commercial galleries. The Esther Schipper Gallery in Berlin, for example, has been particularly focused on revealing aspects of General Idea’s work that were previously unknown. Other galleries, including Mai 36 Galerie in Zürich and Maureen Paley in London, are showing General Idea at art fairs internationally as well as in their exhibition programs. The group has also continued to receive accolades. Most prominently, in 2011 AA Bronson accepted on behalf of General Idea the Chevalier de l’ordre des Arts et des Lettres from Frédéric Mitterand, then Minister of Culture of France.

Bronson maintains a successful solo art practice. He currently lives in Berlin.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements