Jean Paul Riopelle’s career as an artist was productive, extending more than fifty years and filled with unceasing, assured practice. It is marked by free experimentation and intuitive exploration. A multitude of techniques characterize his style: the academic approach of his early years, focused on “copying” nature, which was taught at the schools of fine arts in Montreal and Quebec City; the distinctive “mosaic” technique of his bold multichromatic work of the 1950s, which retain a sculptural effect; his 1960s return to sculpture; the printmaking and collage; and finally, the audacious spray-paint medium that he took up during the final years of his career. From first to last, Riopelle’s artistic journey was remarkable.

The Academic Technique

From about 1936 to 1941, as a student of the realist sculptor Henri Bisson (1900–1973), Riopelle was instructed in the academic tradition. His painting Still Life with Violin (Nature morte au violon), 1941, shows Bisson’s influence. The work depicts a vanitas, a symbolic visualization of the ephemeral nature of all the arts. Music, literature, and sculpture are subtly represented by a violin, a metronome, a book, and other transitory objects in an arrangement reminiscent of those in still lifes by Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), work that Riopelle admired despite his mentor’s dismissal of it. The irregularly angled leaf of sheet music is visible to the viewer while the other objects are held together in a delicate balance that is an uneasy combination of the artist’s competing influences.

While at art school, Riopelle studied traditional academic theories, in which drawing means at once the physical act of working on paper and the underlying purpose or design of the composition—that is to say, it represents the idea that takes intellectual shape before its execution as an image. For many years, drawing was considered the purest form of expression. At the time of Riopelle’s training, it was still given the greatest emphasis in art schools—and line drawing was a technique taught to students early on; they were tested on their ability to draw accurately and faithfully from nature. Riopelle’s second mentor, Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960), recalled that during his time at Montreal’s École des beaux-arts, its first directors, Emmanuel Fougerat and Charles Maillard, never stopped repeating, “Drawing, drawing, drawing again . . . first, last, and always, drawing.” Bisson, Riopelle’s teacher, no doubt gave him the same instruction. During his time at the “bissonnière” school, he would have spent countless hours copying Old Master works.

An example of this influence is apparent in Still Life with Violin: pictured is a head of a Roman emperor, probably Julius Caesar. The art school would have collected such plaster reproductions because of their use in training artists in the study of chiaroscuro and contour before the application of colour. Apprentices such as Riopelle learned drawing in stages: first, they copied from engraved reproductions of works of art by the great masters; second, they drew from a three-dimensional model, often a reproduction such as this Roman emperor’s head (a copy of an ancient sculpture); and finally, the culmination of every drawing course: drawing from nature, using a life model. During the Italian Renaissance, the artists of Florence were devoted to the practice of drawing, while the Venetians, like the great Titian, were known for their mastery of colour.

Still current when Riopelle was a student was the idea that the birth of drawing could be; traced to ancient accounts, particularly to a fable by Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE). In it, Kora, daughter of the potter Butades of Sicyon, fell in love with a young man who was leaving to travel abroad. She decided to immortalize his silhouette in a picture to comfort her in her loneliness while he was away. During the seventeenth century, Johann Jacob von Sandrart immortalized the story in an engraving that was published in an early treatise on the arts. The fable of Pliny was still popular during the twentieth century and teachers like Bisson continued to emphasize the importance of drawing as a result. Even if Riopelle did not pursue a career within it, academic painting was nevertheless the foundation of his apprenticeship, as it was for most of the painters he admired, such as Claude Monet (1840–1926), and the majority of his contemporaries.

The Mosaics

Riopelle’s paintings of the 1950s belong to his “mosaics” period. It is not clear who first spoke of mosaics in connection with Riopelle. Yseult Riopelle, one of his two daughters and the author of his catalogue raisonné, suggests that the comparison may have originated with Georges Duthuit (1891–1973), who was the son-in-law of Henri Matisse (1869–1954). Duthuit, who married Matisse’s daughter Marguerite, was a great defender of contemporary painters, including his father-in-law Henri, Nicolas de Staël (1913–1955), Bram van Velde (1895–1981), and Riopelle. An art historian who specialized in Byzantine and Coptic art, Duthuit was familiar with the mosaic tradition practised by the Byzantines from the fifth to the fifteenth century.

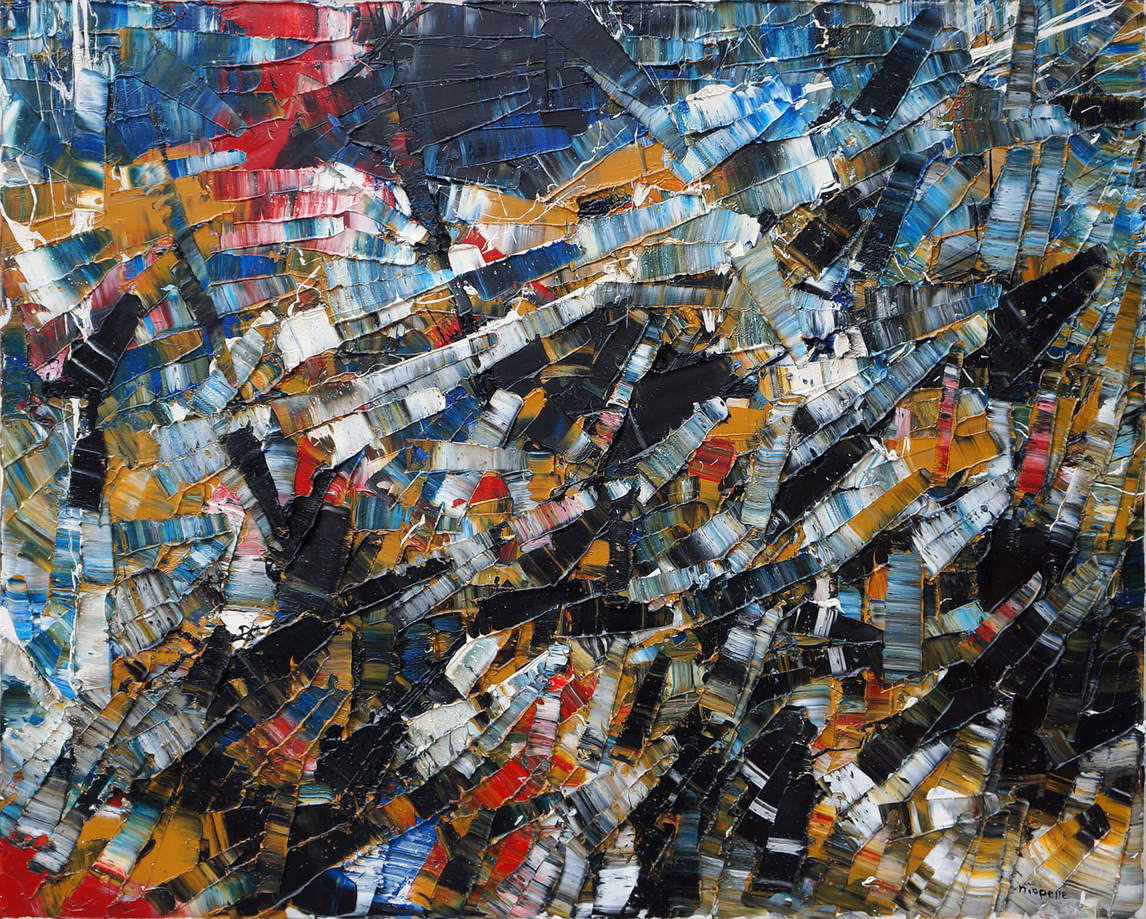

The “mosaic” effect in Riopelle’s work is derived from his use of the palette knife to directly apply paint on the surface of the canvas, giving each dab of colour a sculptural character. The juxtaposition of colours in a work such as Composition, 1954, suggests the appearance of a mosaic—that is, an assemblage of tesserae, which are small coloured squares of marble, stone or glass placed close together and affixed to a wall to form a picture. Riopelle’s rhythmic and irregular applications evoke the square shapes of tesserae and the paintings are reminiscent of Byzantine mosaics in their use of geometric assemblages, harmonious colours, and vivid materiality.

According to Pierre Schneider (1925–2013), in an affirmation echoed by the critic René Viau, it was around 1949 that the painter abandoned the brush. For Riopelle, the brush had become a limitation and hindrance as he moved toward creating ambitious abstract compositions characterized by generous applications of paint in many colours. This change in pictorial technique may seem of little consequence today. After all, Riopelle simply decided to use one tool instead of another. How could that have influenced the artist’s conception of a picture, his style, or his very understanding of painting? In fact, the decision to abandon the brush had a profound effect on Riopelle’s art and his subsequent body of work. The move took Riopelle as far away from his academic training as he could imagine. Without drawing, without figuration, without a brush, he was forced to rethink how he understood pictorial space, and he arrived at a new way to apply paint, achieving exceptional results in the process.

Not only did the palette knife introduce a fundamental change to the way Riopelle thought about the act of painting, but it also added an element of chance and a loss of visual control. Before he applied paint to canvas, he would first load his tool with different configurations of colours straight from the tube. Once he pressed the pigment against the composition, he could move, push, and shape the paint without seeing the effect. In this way, the outcome of his act remained unknown until he could see the results. As Riopelle progressed across the canvas, he discovered the painting as he painted it. For Riopelle, this loss of visual control clearly distanced his work from that of the Automatistes, who in his mind had never abandoned it in their production. Much earlier in his career, Riopelle had called for “hasard total,” or “absolute chance,” as the basis for a work of art, and that early demand is a clear indication of the direction of his later works, particularly the mosaics.

Because Riopelle was an academically trained artist, we must consider his art as an example of working within and outside of the rules of the discipline. Throughout his early and mid-career, he did his utmost to remove any question of the skilled hand from his production, taking away the painter’s brush and any semblance of figural line. This conscious act is an obvious reaction to his training in copying and drawing under Henri Bisson. The question of the hand of the artist, or the trace left by the artist, in the act of making their art never left Riopelle’s mind. He simply searched out new ways in which to express it. Take, for example, a detail from the 1956 piece Encounter (Rencontre); Riopelle leaves multiple and recurring marks, or traces, which evolve along the surface of the canvas. These imprints reveal Riopelle’s movements and are a record of the process of making art. While this might seem as trivial as the changing of a tool, his interest in this idea of record, of trace, and of being there, would increase during his final creative period. He became fascinated by what we leave behind.

The mosaics lasted only a decade. By the 1960s, he wielded the palette knife in new ways, creating marks that he could see and sculpt along the way. Untitled (Sans titre), 1965, is a prime example of this style. Gone are the separate and distinct tiles of the mosaic works of the 1950s, that sense of an artist in search of a loss of vision and line. They are replaced with something new; now, the viewer can follow the path of the palette knife as it moves, leaving trails that sometimes look as if a finger has been drawn through the material. The grooves sometimes form thin stripes, sometimes wider bands, and they appear to fragment when they meet each other. The coloured areas are also more varied, resulting in a composition full of new possibilities.

At first, when works in this new style began to appear, collectors accustomed to the mosaics were bewildered and only slowly began to take an interest in them. His 1960s works in particular were noted because they became much wider, a trend that is referred to as “abstract landscapism.” Sales were initially affected, but Riopelle did not return to his previous art-making technique. His new freedom of execution led him to return to figuration, to the owls and snow geese of his art during the 1970s and beyond.

Sculpture

Even though Jean Paul Riopelle would not make sculpture a serious component of his practice until the 1960s, the medium fascinated him from a young age. On the origin of this interest, he noted: “when I was small—and still today when I get the chance—I made snow sculptures. Starting with the traditional children’s snowman, I would create fantastic improvisations to which my bronzes owe a great deal.”

Riopelle’s earliest documented sculptures date to 1947: works of modelled small clay figures, depicting raw earth, the results of which he photographed. Aside from these pieces, the sculptures from the artist’s early years are gone. Riopelle’s attention to the medium lay dormant throughout the 1950s.

This changed shortly after Riopelle moved to France when, during the 1960s, he returned to sculpture as a way to “break away from the habits of painting.” In part, this renewed interest was one of convenience; Riopelle could now afford to employ skilled assistants to help him execute his ideas. At the Berjac Foundry in Meudon and later the Clementi Foundry, he developed a unique casting method. Riopelle noted, “the caster’s trade is one of the finest in the world. I once wanted to be a mechanic, and before that a hockey player. Later, it was the occupation of the caster that seemed to me the most fulfilling.”

Not until 1962 were Riopelle’s sculptures exhibited for the first time as part of an exhibit at the Galerie Jacques Dubourg in Paris. Among the works that were likely part of the show was B.C., a small sculpture only half a meter in height. It is characterized by jagged edges, with elements that would collapse were it not for the bronze holding the sculpture in place. Many pieces made by Riopelle during this period resemble organic forms and no doubt symbolize a return to his first experiments in clay. Upon seeing this body of work, Pierre Schneider noted that they did not renounce his paintings, but in fact focused the artist and, in the process, appeared to free him.

Typically in sculpture, and especially with bronze works, artists tend to favour smooth creations that blend seamlessly together, accentuating the material’s unique properties. This is not so with Riopelle. Like the artist’s painting, his sculpture is fragmented. Owl A (Hibou A) from 1969–70 (cast 1974), is a notable example. Thin sheets along the base appear layered and the sculpture is perforated by the hands of the artist, as if he modelled it while still molten. Of course, we know this to be impossible. No person can mold bronze as it transitions from a liquate to a solid. Yet Riopelle, using the lost wax method, made his sculptures appear as if the artist had the ability to defy the very tradition he was working within. In doing so he made the medium his own.

The Joust (La Joute), 1969–70 (cast c.1974), is Riopelle’s largest sculptural arrangement. Composed of a central “Tower of Life” figure—reminiscent of both an Inuit inuksuk and a birdbath—surrounded by thirty bronze elements in the form of animals and mythical figures, it introduces the viewer to a complex mythology drawn from Riopelle’s childhood. Titled The Tower (La Tour), this principal component of the work held considerable symbolic meaning for the artist. Of course, Riopelle would never admit this; however, his dedication to picturing and sculpting the natural world around him in novel ways is a reminder of the complexity of its influence. That at heart, he was always returning to his childlike fascination of moulding something with his hands.

Printmaking and Collage

When Riopelle first visited New York in 1946, he passed by the printmaking studio of William Hayter (1901–1988). There he met fellow artists such as Joan Miró and Franz Kline, who would become close friends later in life. This was Riopelle’s first encounter with printmaking. During the 1960s while he and Joan Mitchell lived in the French countryside, his interest in it spiked and his first full blown creations received much critical attention.

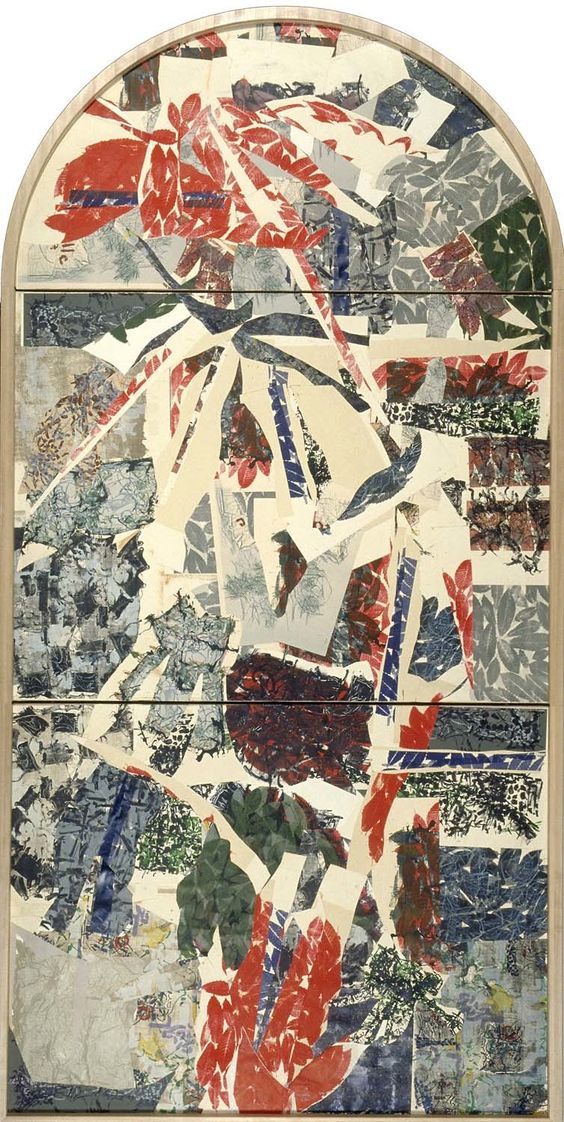

Dense layers of abstraction are visible in works such as Untitled (Sans titre), 1967, a mixed-media piece using the techniques of printmaking and collage. From his studio, Riopelle would cut up his prints and reassemble them into grand new creations. This use of cut shapes is reminiscent of the late work of Henri Matisse, who in his final years began to create beautiful images by cutting up bright pieces of paper and arranging them. Yet Riopelle explored the technique quite differently. His are not bright works marked by clear shapes. They are complex and anarchic patterns reminiscent of his early abstractions. In them, fine line is accentuated by larger and smaller cut up abstraction prints, arranged in a haphazard fashion that shows little regard for the way an image should look. His collage work, grounded in printmaking, is an exploration of potential abstract arrangements that celebrate the chance encounter that occurs when pieces never intended to share the same space are brought into contact with one another.

Riopelle’s interest in printmaking continued upon his return to Québec. He developed an important collaboration with the printmaker Bonnie Baxter, and the two worked together, either at Baxter’s Atelier du Scarabée in Val-David in Quebec or from the studio that Riopelle continued to keep in France, from 1985 up to his death in 2002. The practice, she notes, appealed to Riopelle because it allowed him to try out different arrangements. A print could progress and advance based on reworking, layering, and then be deconstructed and reformatted as a collage. Of his practice, she observed, “Just as in his painting, Riopelle was daring and experimental; he liked to mix it up and was allergic to abiding formulas.”

The Aerosal Spray Can

At the end of his career and afflicted with osteoporosis, Riopelle became fascinated with spray paint. He saw it as an innovative tool for creating art that was easily accessible given his physical limitations. There were precursors to this technique for the artist, who had during the 1950s worked with a pipette (an open-ended pipe that allows one to release drops of paint) and in the 1960s with a Fly-Tox hand sprayer (to manually release pumped paint). In the 1970s, Riopelle discovered spray paint and used it to develop many new and extremely varied motifs, techniques, and vocabularies—including a unique form of interplay between positive and negative space.

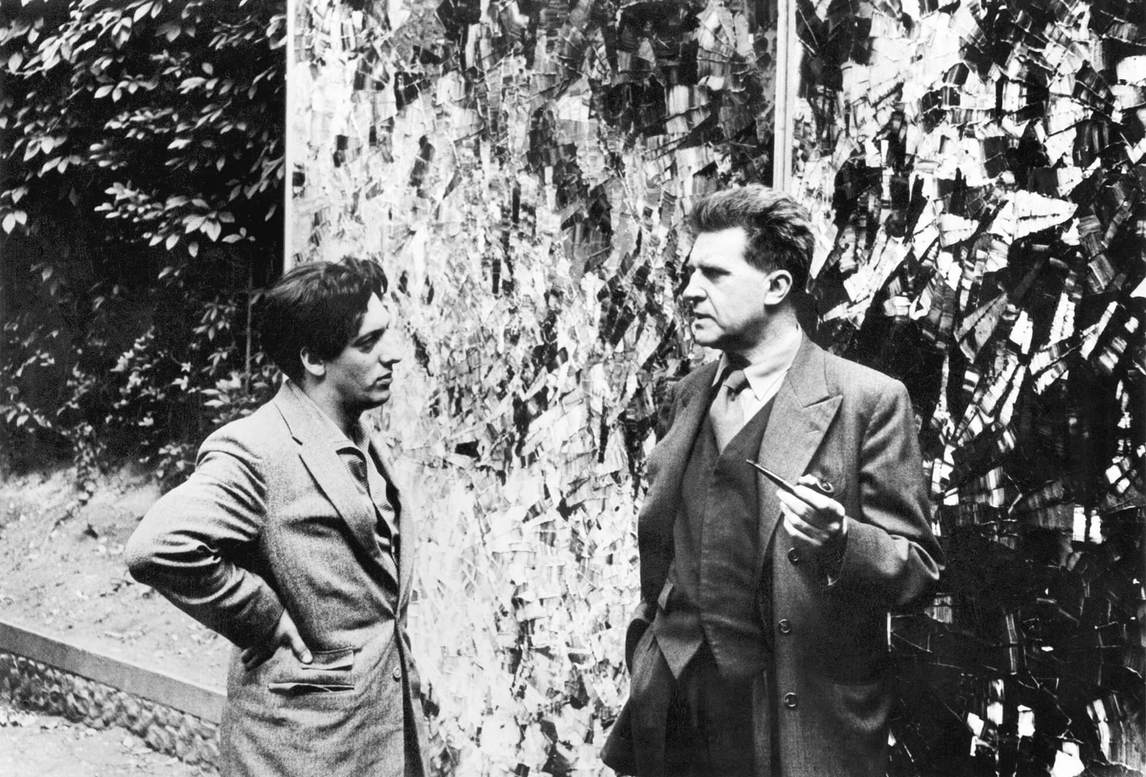

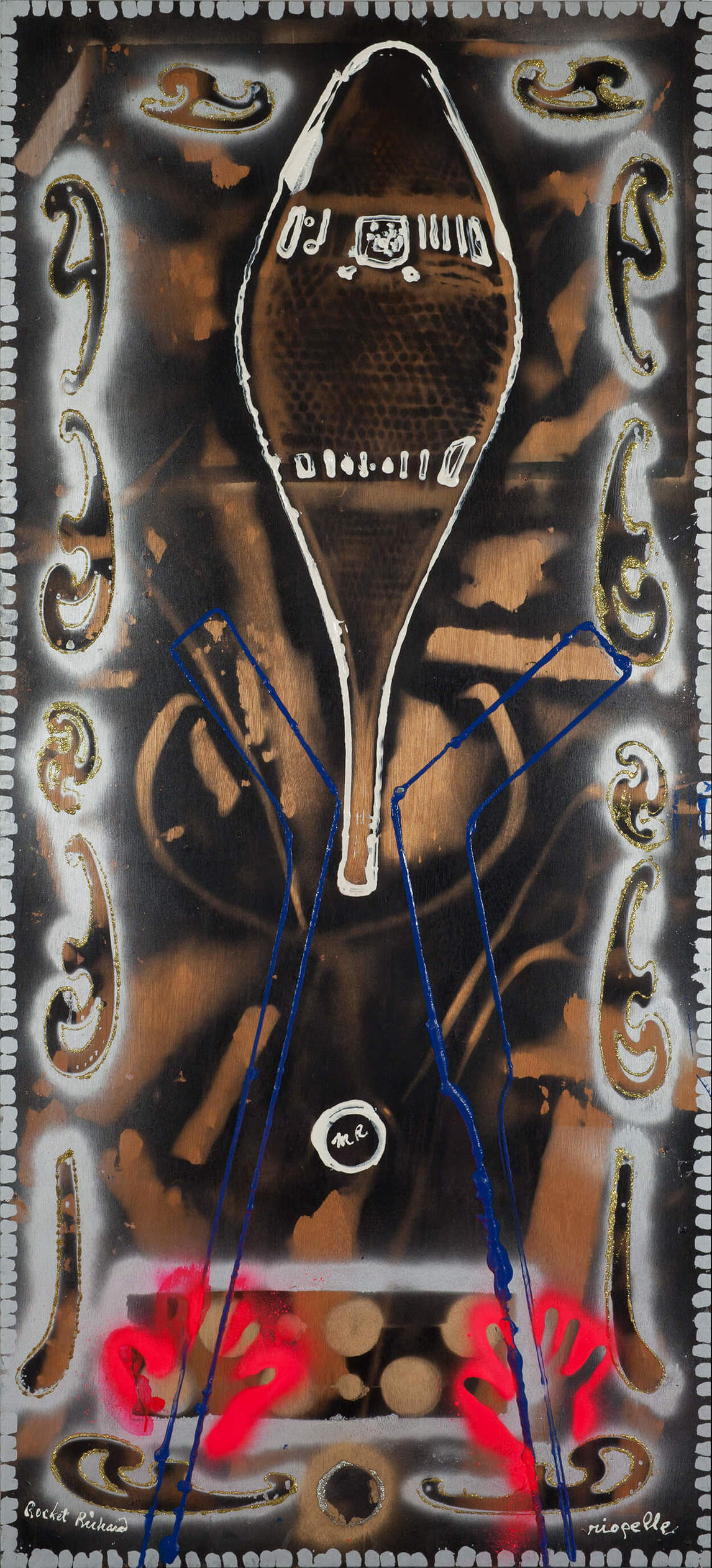

Unlike the pipette or atomizer, which are activated by pumping a liquid up through a tube or spritzing or blowing it out, the aerosol can makes it possible to spray bursts of colour with the simple touch of a finger. Riopelle was delighted with the fact an object could be laid flat on a canvas and sprayed, which would create a negative image similar to a cut-out beneath it. An example of the process is found in photographic documentation of Riopelle and the hockey player Maurice Richard (of whom Riopelle was a passionate fan in his youth) as the artist creates Tribute to Duchamp (Tribute to Maurice Richard) (Hommage à Duchamp [Hommage à Maurice Richard]), 1990. As in much of Riopelle’s oeuvre, this painting, which has two sides, shows the return of his fascination with the hand, yet this time it is the hand of the hockey player that Riopelle intends to mark. Richard lays his hand flat on the canvas and Riopelle records the negative imprint, then records his own hand, that of the artist using the spray can. It is through this act that Riopelle enters himself into a millennia old dialogue about art that has been ongoing since the time of the Paleolithic Chauvet Cave painters, the question of what remains.

The title Tribute to Duchamp (Tribute to Maurice Richard) (Hommage à Duchamp [Hommage à Maurice Richard]), 1990, pays homage not only to the great hockey player but also to one of the most important artists of the twentieth century, Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968). Duchamp contributed the readymade to art history in 1917 by turning a urinal on its back, titling it Fountain, signing it with an invented name, and declaring it a work of art. Tribute to Duchamp (Tribute to Maurice Richard) (Hommage à Duchamp [Hommage à Maurice Richard]) employs readymade items, but they are used in reverse. Like the imprint of the hand, these are imprints and outlines of tools. The tool of the architect, the French curve template, borders the painting. The tool of the trapper, the snowshoe, is in the upper half while two hockey sticks, tools of the player, are outlined in the lower half. These silhouettes are all that remain of the objects that once rested on the work. After he completed it, Riopelle gave the painting to Maurice Richard, who later donated it to the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

Using spray paint, Riopelle developed his skill and began to search for every possible way he could of present the negative imprint of an object. In Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg (Hommage à Rosa Luxemburg), 1992, the technique finds its most spectacular application. The imprints created by the spray paint are now lighter or darker, depending on how the artist chose to emphasize them in different areas of the composition. The dominant visual effect is now ethereal as opposed to dark, with constellations of material sprayed across the canvas that create an impression of soft, almost muted, shapes. The colours are festive, tender, and beautifully vivid, despite the contrasts of black and white. Some areas show a clear X-ray effect, with negative imprints captured in white paint against a black background. Elsewhere, the bright colours enhance and overlap paler shapes. They reveal fiery-red birds, or frosted bright blue and white birds that flutter against shaded forms of deep red, rose-pink, green, yellow, and orange—the whole appears temporary and, yet, at the same time has an intense monumentality.

The suite of thirty paintings that makes up Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg is extraordinarily coherent, despite the density of the overall composition. The colours work to create linkages between them while the forms are repeated and transformed, fading and falling into a rather mysterious repertoire of objects. Everything contributes to the whole, from ordinary bolts and a white goose shot by Riopelle himself, to ferns and common tools, including a drill. All these objects are easily recognizable, but they are not portrayed by real contour lines. They appear as shapes against blurred or hazy backgrounds, and the impression they leave is one of absence as opposed to presence. They are ghosts, both animate and inanimate. Traces of a life lived to the fullest.

A Career of Transformations

Riopelle’s career inspires reflection on the evolution of art over time. The art that we recognize as historic is steeped in the academic tradition. Through training, the artist learned to hide their brush strokes, to disguise the work of painting the background, to eliminate the marks of hesitation that occur while tracing an outline, to paint over ugly colours, and to never exhibit a failure. Looking at a painting by Nicolas Poussin (1594–1655), who would know that he ever hesitated? This is what Riopelle learned from his teacher Bisson: to create works that were pure “copies of nature,” to hide their secrets and the presence of the artist.

Modern and contemporary art proceeds in a completely different way. No contemporary artist would hesitate to show us the genesis of a painting. Today, painters intentionally leave visible traces, inviting viewers to redefine the work in their own way. When Riopelle moved away from the academy and toward the methods of Automatism, Lyrical Abstraction or American Abstract Expressionism, he began to include the viewer as a witness to the origin of each painting. Every application of paint is visible on the surface of the finished work. We see it repeated in the famous mosaics of the 1950s; later, we follow the traces of palette-knife marks as his work develops in a new direction, which leaves us to visually reconstruct his painting process.

Finally, when Riopelle turns his attention to spray paint, his interest in the mark, the trace, the hand of the painter, returns with full force. We understand that the shapes that appear on the canvas, such as those of the wild birds, owls, and rabbits, of his last great work, The Happy Isle (L’Isle heureuse), 1992, are the negative imprints of objects first laid physically on the canvas by Riopelle. Yet surprisingly, they are now combined with the line and pictorial techniques of the classically trained painter, made visible by the line work that gives precious detail to elements of the composition. In this culmination, Riopelle’s entire production intersects, resulting in an image solely individual in its execution. Thus, at the end of his career, the genesis of form no longer holds any mystery—Riopelle, by his own creative process, deliberately exposes it. This creation of another world.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements