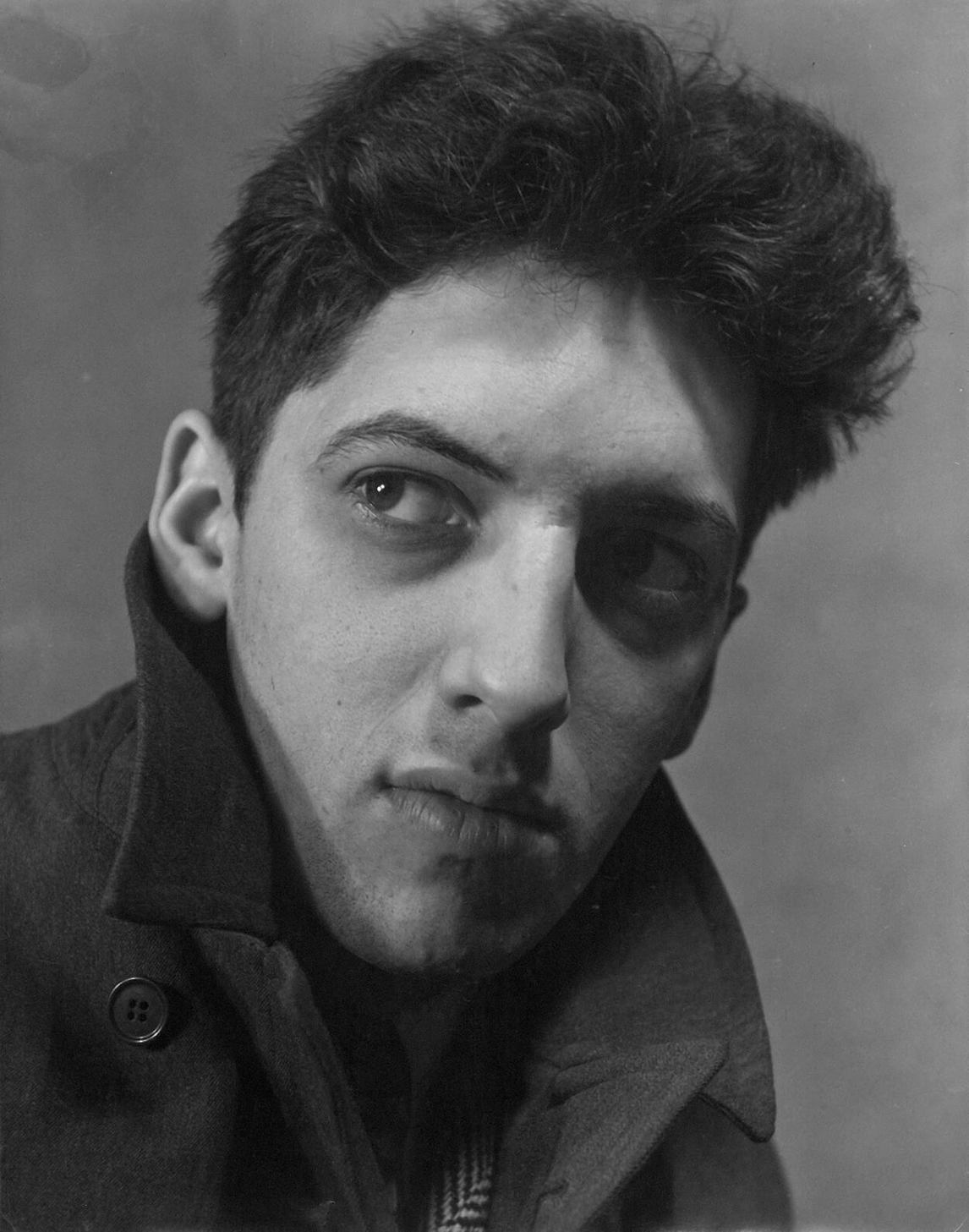

Jean Paul Riopelle (1923–2002) is one of Canada’s most significant artists of the twentieth century. Attracted to painting from a young age, in 1943 he enrolled in the art program at Montreal’s École du meuble, where he met the painter Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960). The encounter was life changing for Riopelle, who went on to join the Automatistes, an influential group of Québécois artists, and to be a signatory of their landmark 1948 manifesto, Refus global. He later settled in Paris, where he became the most famous Canadian painter in Europe and the rest of the world. Stylistically linked to many of the most important art movements of his time, Riopelle’s legacy is his large and diverse body of work, expressing both abstraction and figuration in imaginative and surprising ways.

Youth and Formative Years

Jean Paul Riopelle was born in Montreal on October 7, 1923, into a prosperous family. His father, Léopold, was a trained carpenter who became successful in real estate and construction. His trademark was the exterior staircases so typical of Montreal homes, especially in the working-class neighbourhood near de Lorimier Avenue where the Riopelles lived. Jean Paul’s mother, Anna Riopelle (his parents were cousins), was the only daughter of a businessman, from whom she inherited several properties. Jean Paul’s delight in nature was apparent from his earliest years, as can be seen in a photograph taken when he was about five, showing him triumphantly returning from a fishing trip.

Jean Paul’s sibling, Pierre, was three years his junior. On November 8, 1930, when Jean Paul was only seven, he and his family were faced with Pierre’s tragic death. The Catholic burial rite for children required that the deceased’s clothing, the church hangings, and the liturgical accessories all be white. According to Hélène de Billy, in her biography of Riopelle, for some time afterward “every reminder of snow meant abandonment, suffering, and death to Riopelle. Such an association with deep loss may also have contributed to the initial predominance of vivid colour in his work.

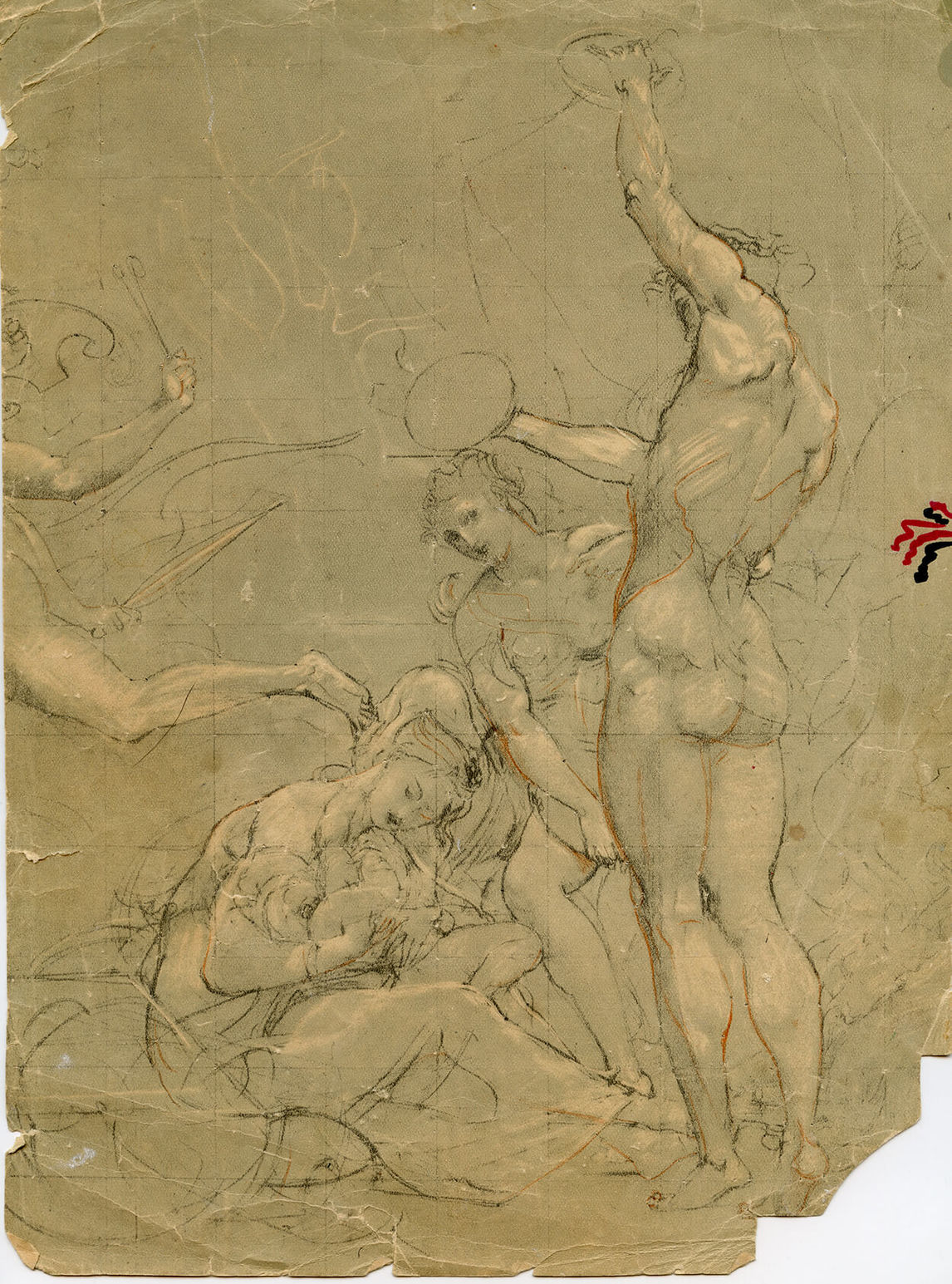

Riopelle began his education in his neighbourhood, at the Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague school. In 1936, when he was thirteen years old, his parents responded to their son’s growing interest in art by encouraging him to take the drawing and painting classes that Henri Bisson (1900–1973) taught in his home on weekends. Bisson’s practice was predominantly sculpture, based on drawing from life models, and some of his works were shown at the annual Salon du printemps in Montreal (1934–36, 1938, 1942–43). He was the principal artist of the Monument to the Patriots (Monument à la gloire des Patriotes), 1937, a centenary project memorializing the resistance fighters in the Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837 to 1838 (known in Quebec as the Patriots’ War), as well as another monument recognizing Jean-Olivier Chénier, a Saint-Eustache patriot who died in that same conflict against British colonial rule.

Riopelle had many happy yet conflicting memories of his drawing teacher and what he later called his “bissonnière school.” Bisson advocated that artists should copy nature as realistically as they could, which was a philosophy of art that condemned anything that departed from faithful representation. In particular, his dislike of the Impressionists would have a profound effect on Riopelle, who would soon come to enjoy their expressive use of paint and novel combinations of colour.

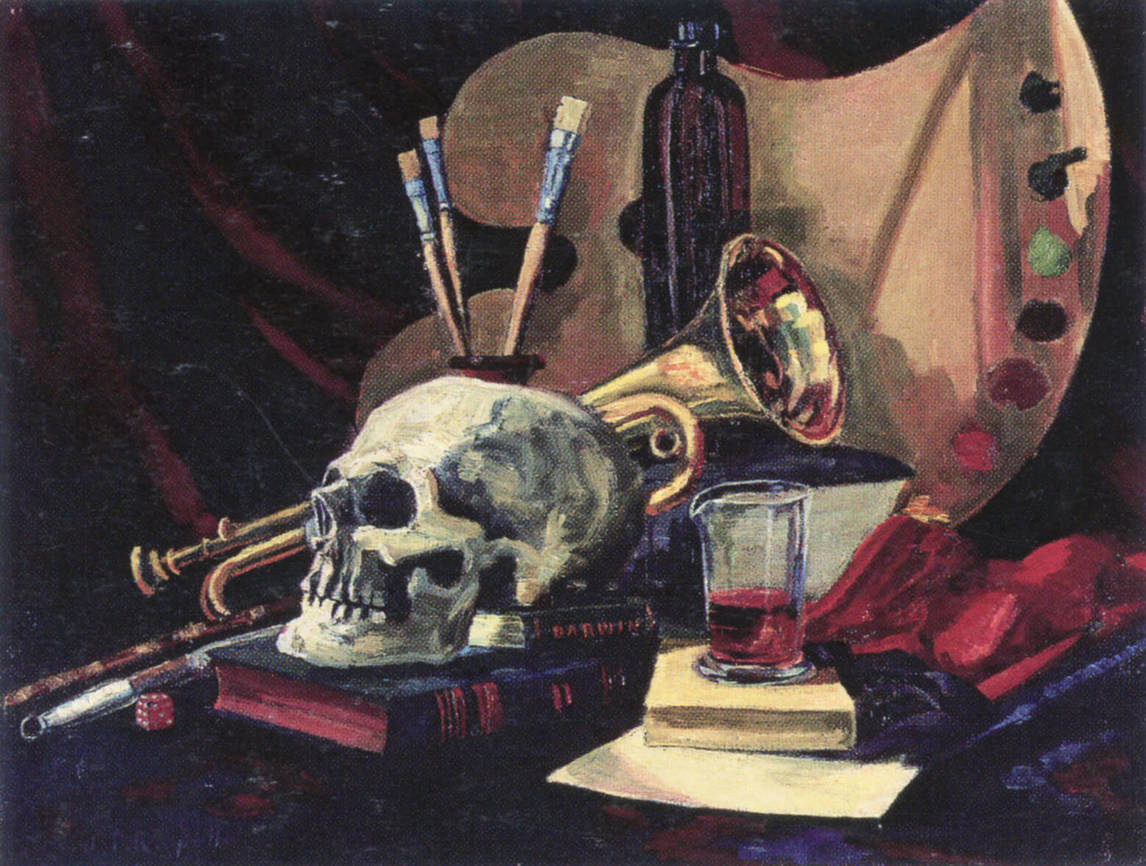

Many of Riopelle’s earliest works can be traced back to his time with Bisson. An example is Riopelle’s Very Still Life (Nature bien morte), 1942, which is, according to Henri Bisson’s daughter, Yvette, a copy of a work by her father. Art historian Pierre Schneider (1925–2013) observes that it is modelled after Bisson’s Darwin Vanitas (Vanité au Darwin), n.d. Riopelle’s interpretation depicts a vanitas of the arts (paintbrushes, palette, bugle, books) and sciences, and he, ever the wit, called it Very Still Life.

The École du Meuble

Riopelle’s parents wanted to see him concentrate on a more profitable profession than painting, so he was enrolled in 1941 at the École polytechnique de Montréal, where he studied architecture and engineering. The following year, still enamoured with painting and having failed at the school, he enrolled in the École des beaux-arts, only to move on shortly thereafter to the École du meuble.

Less academic than the École des beaux-arts then under the direction of Charles Maillard (1887–1973), the École du meuble, with its broader curriculum, gave Riopelle the opportunity to take courses from Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960), Marcel Parizeau (1898-1945), and Maurice Gagnon (1904–1956). He quickly fell in with many of Borduas’s students, some of them future members of the Automatistes, such as the painter Marcel Barbeau (1925–2016) and the photographer Maurice Perron (1924–1999), whom Riopelle had previously met at the Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague school during his teenage years.

At the beginning of his training at the École du meuble, and still influenced by Bisson’s lessons, Riopelle resisted Borduas’s style of teaching. Borduas was interested in abstract painting, and he encouraged his students to let go of their preconceived ideas and paint from a new perspective. At first, Riopelle could not understand why Borduas graded his academic drawings as the lowest in the class. However, Riopelle soon embraced his teacher’s direction and began to excel. Borduas was a committed teacher, eager for each student to develop a unique voice and his courses were formative for them as both artists and humanitarians. For Riopelle, Borduas’s automatic writing and painting exercises, based in Surrealist techniques that encouraged spontaneous thought and embraced the unconscious imagination, were decisive; as a result, he abandoned Bisson’s academic teaching.

While still a student, Riopelle spent part of the winter of 1944 to 1945 with Borduas in order to focus on his study of painting. Borduas had recently returned to his birthplace of Saint-Hilaire (now Mont-Saint-Hilaire), thirty-five kilometres northeast of Montreal, and his home had become a safe haven of artistic incubation for the young Automatistes. Together, the group began to explore radical ideas about art and politics that would see their culmination some years later in the creation of the Refus global manifesto, but they were, according to Riopelle, out of step with the international scene. Ideas about art, and specifically about painting, took time to travel from the artistic centres of New York City and Paris to Montreal, and Riopelle felt that, as a result, the group lagged behind.

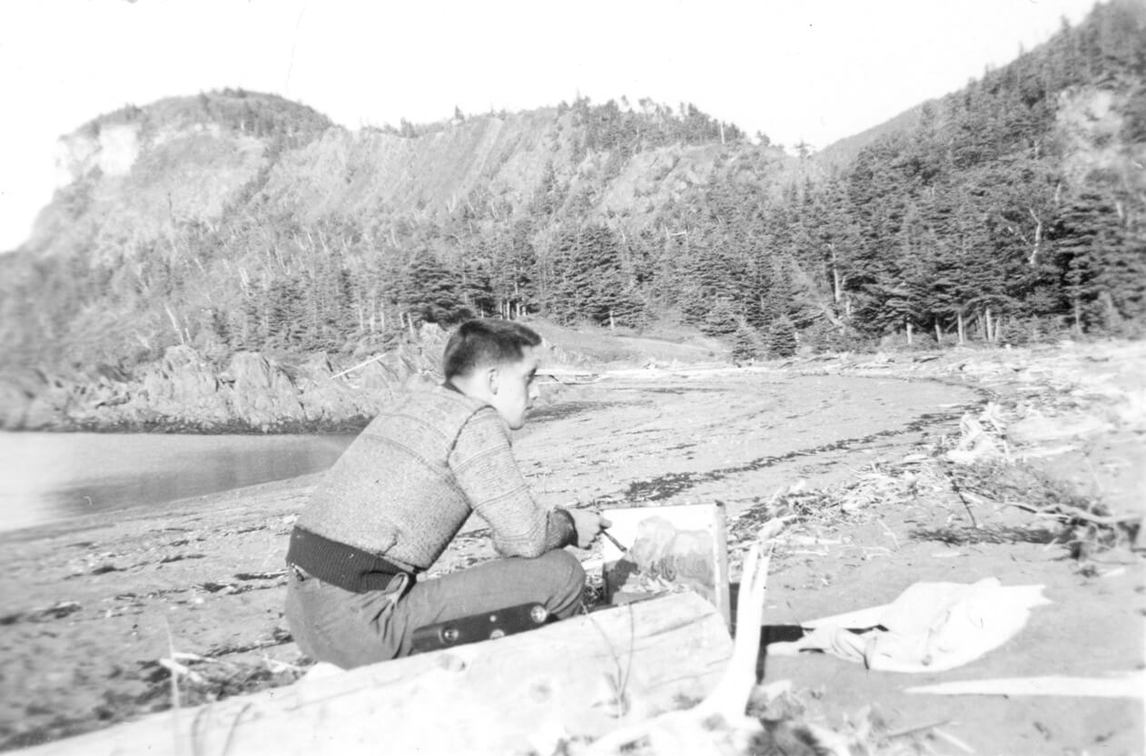

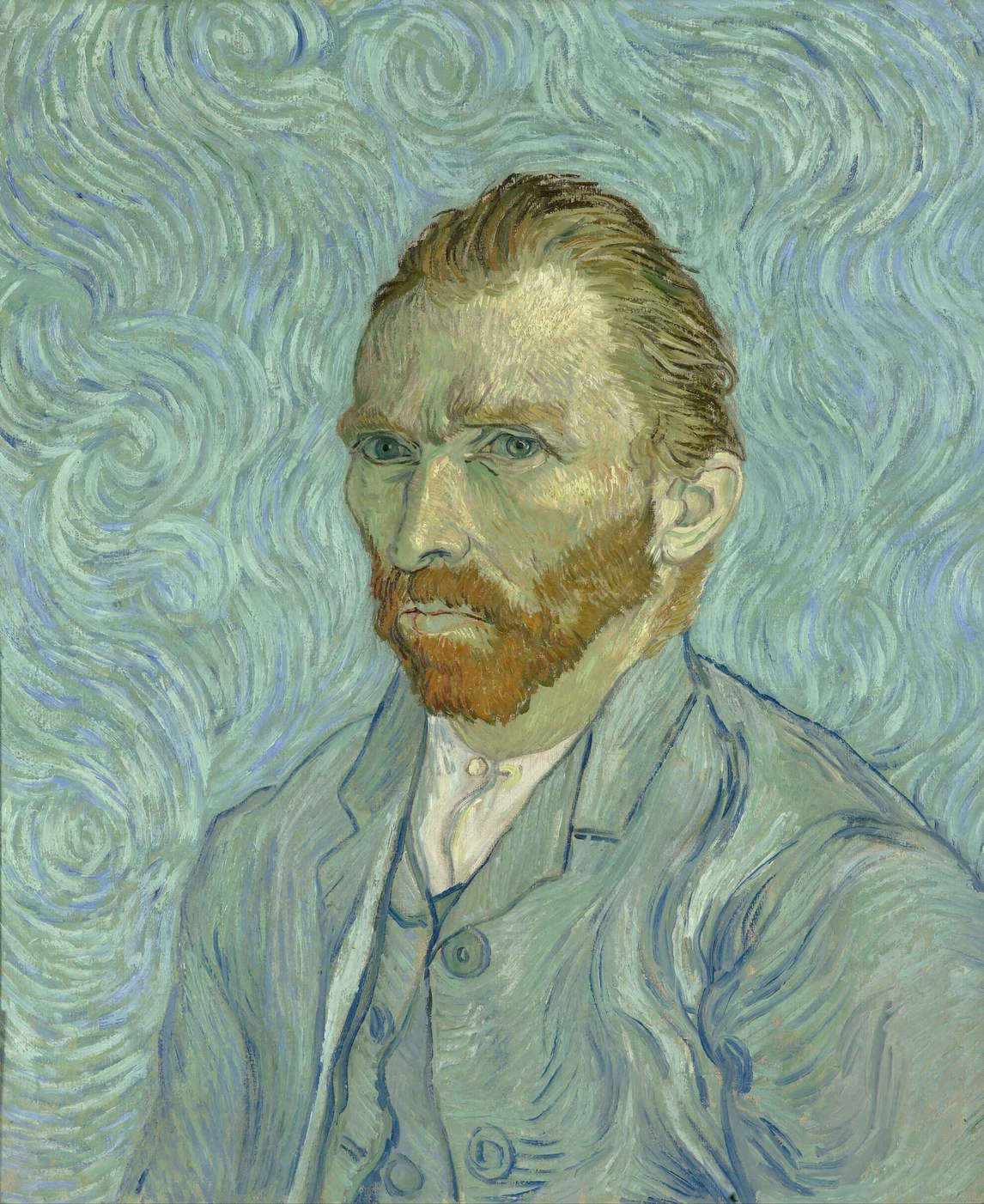

Another crucial event of this period that marks Riopelle’s transition from the academic painting of his early days to the abstraction for which he would become known is his encounter with the paintings of Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890). In 1944 a major Dutch art exhibition at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts included the artist’s work. Riopelle was struck by Van Gogh’s Post-Impressionist style. Not long after seeing the works, he travelled to Saint-Fabien, a small village on the Lower Saint Lawrence. There Riopelle produced his first “abstraction”: a representation of a water hole left on the shore by the tide that his friends described as “non-figurative.” Riopelle would later claim to have painted exactly what he saw. Unfortunately, there is no record of this decisive work.

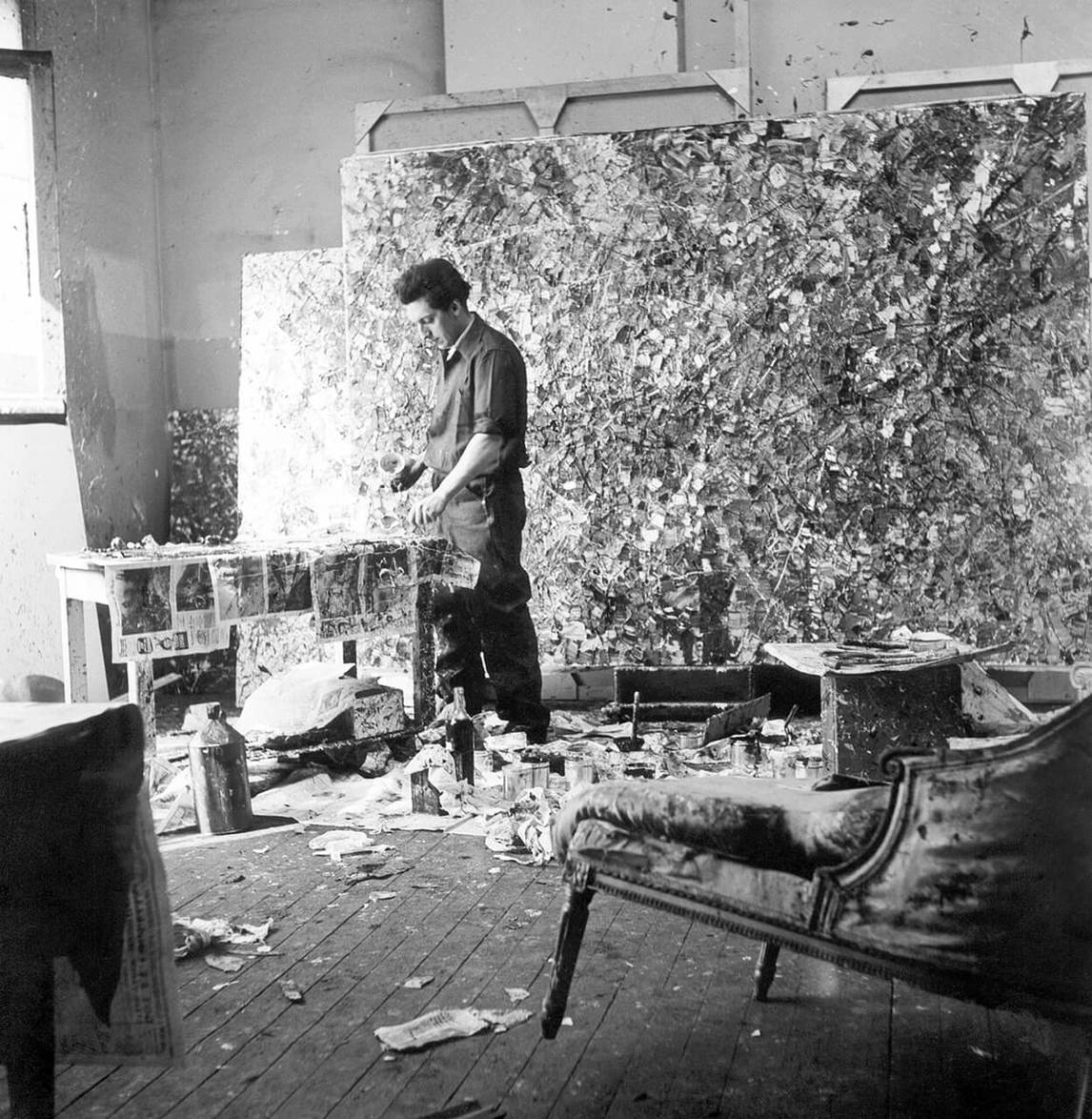

The Alley Studio

In 1946 Riopelle’s friend Marcel Barbeau rented for $10 a month (using the money he made as a grocery store attendant) a “studio,” or rather a shed, overlooking an alley between Saint-Hubert and Resther Streets in Montreal. Riopelle, whose newest paintings were no longer appreciated by his parents—his mother actually called his “abstractions” the works of the devil—shared the space with Barbeau and Jean-Paul Mousseau (1927–1991). It was in this makeshift studio that Riopelle, Barbeau and Mousseau began to truly explore the explosive potential of automatism.

Riopelle referred to his early automatism paintings as works of “destruction.” As he would explain, later in his life:

Very few of these paintings lasted, as they were generally easily damaged. They were made with enamel, with car paint, because we didn’t have the money to buy anything else. And besides, we painted at such a pace that we used everything we could get our hands on. The most important thing was to paint at all costs, for the sake of painting. It was a destruction, rather than a construction.

From April 20 to 29, 1946, Riopelle took part in the first exhibition of the Automatistes, simply titled Exposition de peinture (Painting Exhibition), at 1257 Amherst Street in Montreal, with Barbeau, Borduas, Roger Fauteux (b.1923), Pierre Gauvreau (1922–2011), Fernand Leduc (1916–2014), and Mousseau. In line with their interests of the time, the works on display were experimental in nature and the exhibition was intended not to commemorate something monumental or lasting but to revel in the joy of the moment. Many of the works were collaborations, as a philosophy of the young artists was to paint not unique works of art but spirited and impersonal automatic creations.

Today, and perhaps in true form with the intent of the exhibition, all that remains of Riopelle’s participation is an account by the journalist and poet Charles Doyon. In an article Doyon mentions three paintings: Thus There Is No More Desert (Ainsi il n’y a plus de désert), All Is Found Again (Tout se retrouve), and Never Did April Appear (Jamais avril n’apparut). While these titles cannot be found in the first volume of the Riopelle catalogue raisonné, it should be noted that Doyon was not a very good source for this kind of information. Known to dabble in poetry, he was not averse to taking liberties with the titles of the works he was reviewing—or to plain and simple make them up.

The First Trips to France

In the summer of 1946, Riopelle travelled to France, a trip he said he had made “à fond de cale,” working as a horse groom as he traversed the countryside. During this formative time away from home, Riopelle was struck by the extraordinary paintings of horses by the Romantic painter Théodore Géricault (1791–1824) that he saw at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen.

Eventually, Riopelle was able to visit the Musée de l’Orangerie in the Jardins des Tuileries in Paris, where he saw the exhibition Les Chefs-d’œuvre des collections privées françaises retrouvés en Allemagne par la Commission de récupération artistique et les Services Alliés (Masterpieces from French Private Collections Retrieved in Germany). The paintings that most interested Riopelle were by Claude Monet (1840–1926), Berthe Morisot (1841–1895), Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721), Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867), and Francisco Goya (1746–1828). Monet in particular would prove to be a lifelong inspiration to the artist.

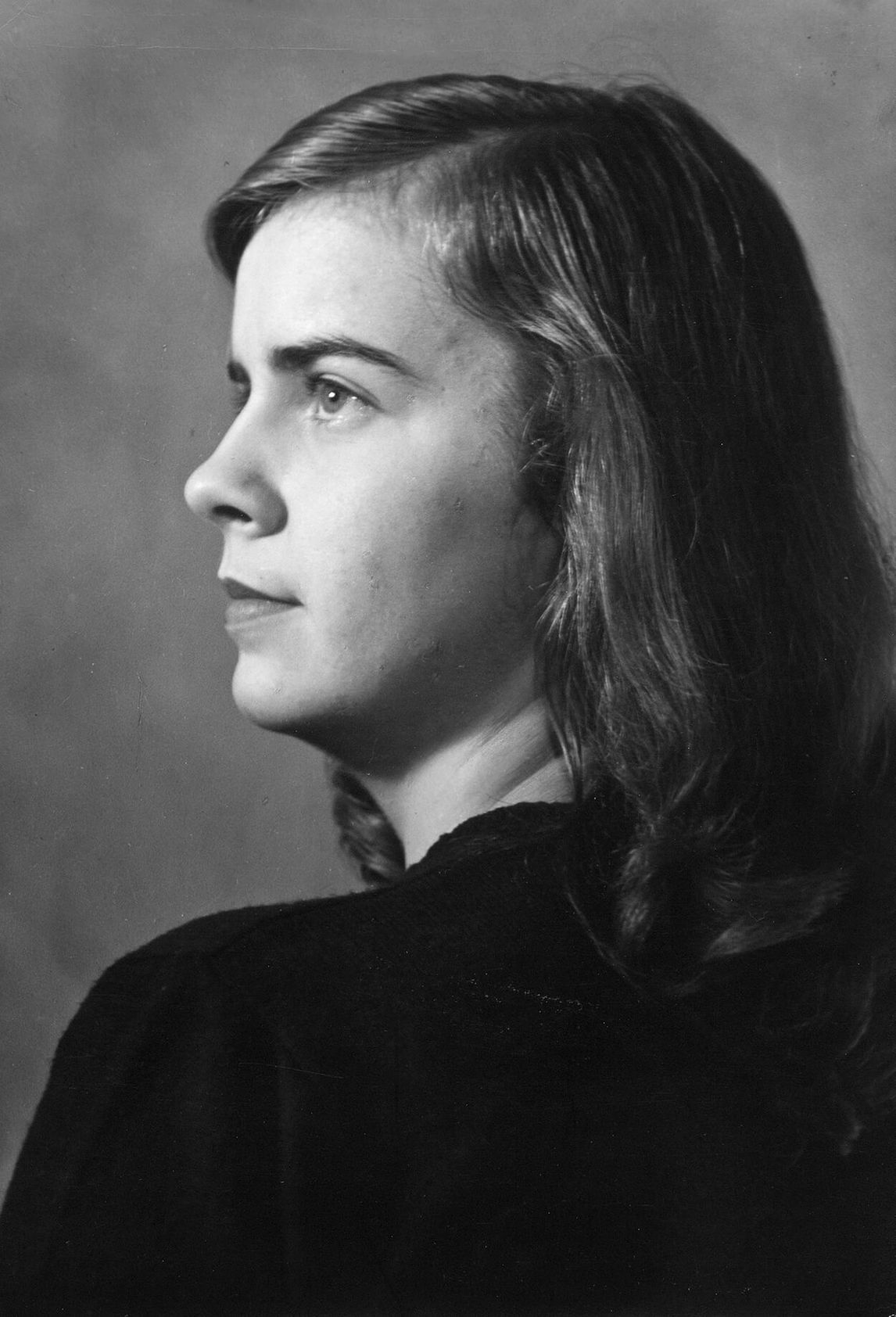

Riopelle called this first trip to France a revelation: “I decided that it was in the Île-de-France [the Paris Region], where the light is the most beautiful, that I would live.” He returned to Canada in 1946 at the end of September and reconnected with his girlfriend, Françoise Lespérance. The lovers went off to New York City for a few weeks in October with Riopelle’s friend the playwright Claude Gauvreau. There, Riopelle visited the studio of the British artist William Hayter (1901–1988) and he became familiar with basic print techniques among other important artists of the time. Once back in Canada, they married on October 30, 1946, at the Church of the Immaculate Conception in Montreal. Riopelle went against the wishes of his parents, who thought the couple was too young. Still, Riopelle’s father gave the newlyweds a house as a wedding gift, which they sold before long, providing them with the means to live and travel as they desired. They chose to start with Paris, and most likely left for Europe on December 9, 1946.

Riopelle soon met the Parisian art dealer Pierre Loeb (1897–1964), owner of the Galerie Pierre, which promoted major Surrealist and Cubist artists, including Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Joan Miró (1893–1983). It was through Loeb that Riopelle met the French writer and father of the Surrealist movement André Breton (1896–1966). Breton invited Riopelle to participate in the major Surrealist exhibition of June 1947, and asked Riopelle to forward the invitation to Borduas and his friends. Riopelle wrote the following to Borduas about his encounter with Breton:

We discussed Automatism and Surrealism in general. Although Automatism is not in his [Breton’s] opinion the only key to this inner world, his reaction to our paintings shows that if among Surrealist painters, Automatism manifested itself only timidly, that was hardly his fault. So, as you can see here, you are invited to take part in an international Surrealist exhibition. This invitation extends to Barbeau, Gauvreau, Mousseau, and Fauteux.

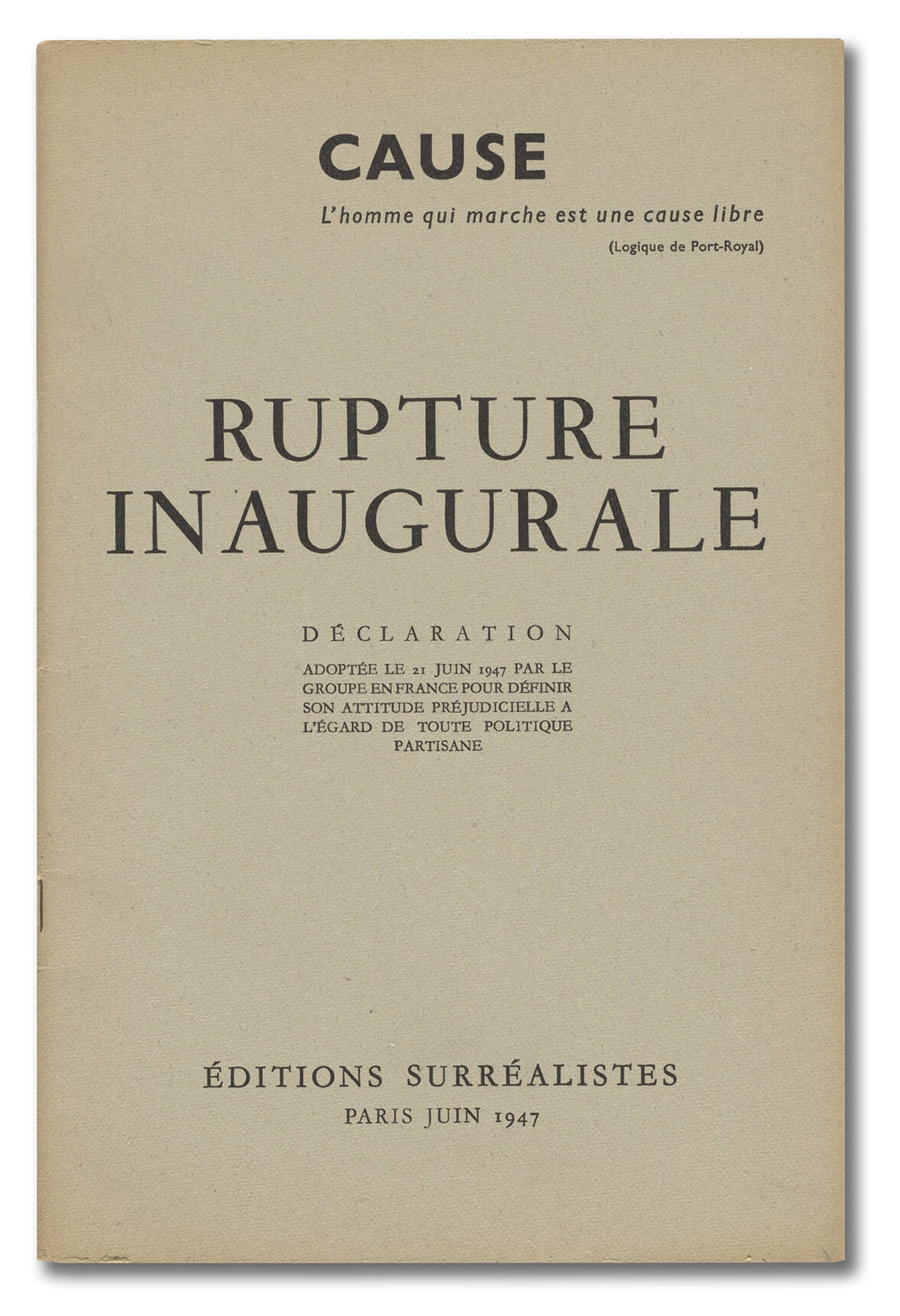

As a result of Breton’s somewhat dismissive attitude toward them, Borduas and the other members of the group decided to postpone their official collaboration with the European Surrealists to another occasion. Riopelle was the only Canadian both to sign with Breton the Rupture inaugurale manifesto, written by Breton’s disciple Henri Pastoureau, and to participate in the VIe Exposition internationale du surréalisme (6th International Exhibition of Surrealism) organized by Breton and Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), held during the summer of 1947 at the Galerie Maeght in Paris. Riopelle showed two watercolours, one of which was Mother Liquors (Eaux-mères), 1947.

Refus global and the First Parisian Exhibition

In 1947 the Riopelles returned to Montreal for their birth of their first child, Yseult. Riopelle soon contributed to a joint exhibition with Jean-Paul Mousseau, held in the apartment of Muriel Guilbault on Sherbrooke Street West from November 28 to December 15. As he reconnected with the Automatistes, he discouraged them from signing the French manifesto Rupture inaugurale and, instead, proposed that they produce their own declaration and take a position against the insularity of Quebec society under Premier Maurice Duplessis (1890–1959), an ultraconservative traditionalist who had won several consecutive elections.

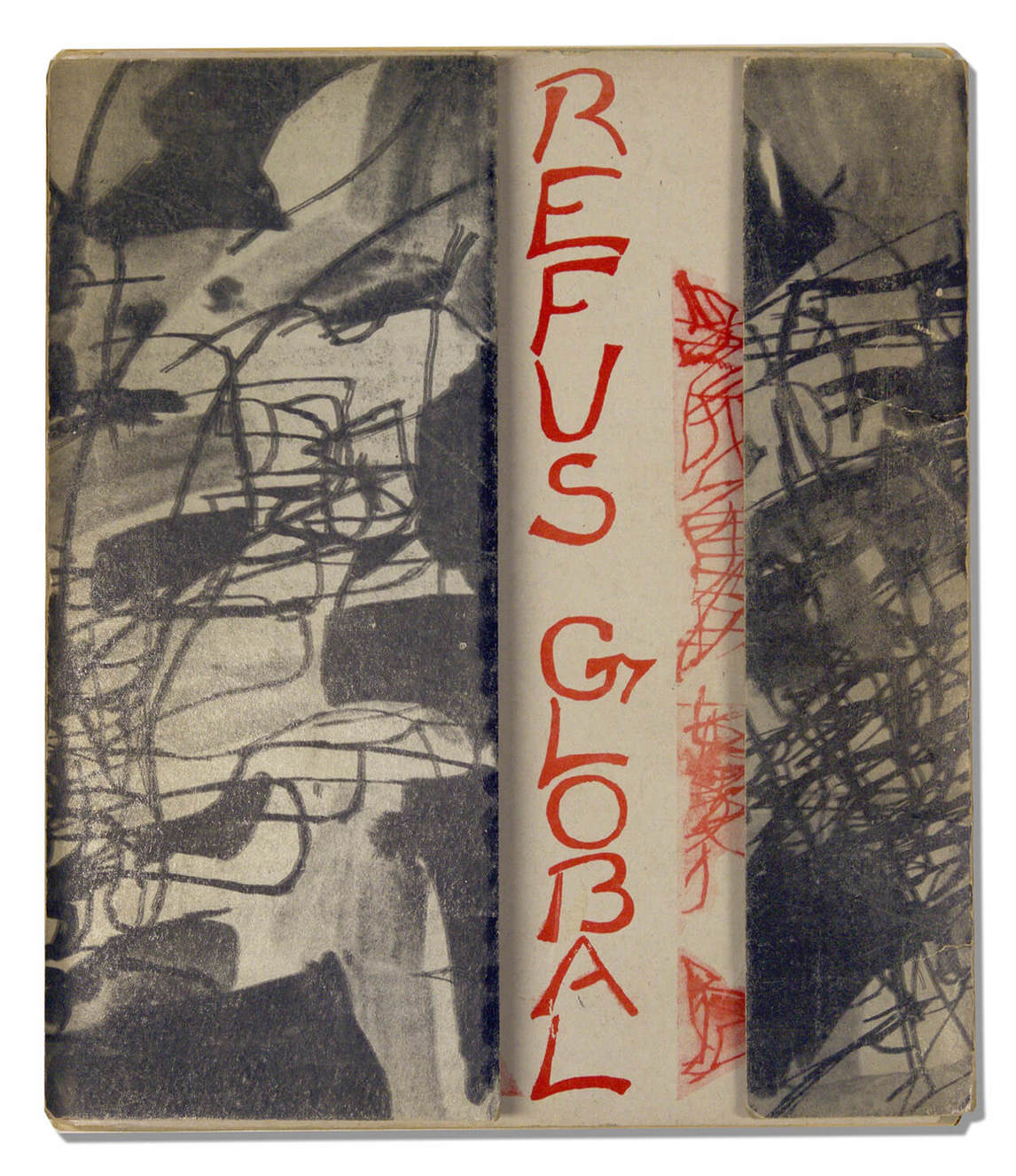

Jean Paul Riopelle and Pierre Gauvreau, cover page of the manifesto Refus global(Total Refusal), 1948, ink on paper, 21.5 x 18.5 cm. Paul-Émile Borduas and other signatories, Refus global, Saint-Hilaire, Éditions Mithra-Mythe, 1948. © Jean Paul Riopelle Estate and Pierre Gauvreau Estate / SOCAN (2019).

It was therefore at Riopelle’s suggestion that Borduas began, in February 1948, to write the principal essay of what became Refus global (Total Refusal), an anti-clerical, anti-establishment, and anarchistic manifesto denouncing the obscurantism of Quebec society at the time. Supplementary texts were written by Pierre and Claude Gauvreau, Françoise Sullivan (b.1923), and Fernand Leduc, among others. Riopelle supplied the watercolour for the cover. Maurice Perron took photographs of some of the group members’ artworks, which were added to complete the publication. There were sixteen signatories: Madeleine Arbour, Barbeau, Borduas, Bruno Cormier, Marcelle Ferron, Claude and Pierre Gauvreau, Muriel Guilbault, Leduc, Mousseau, Perron, Louise Renaud, Thérèse Renaud, the Riopelles, and Sullivan.

At first the idea was to turn the Refus global into a kind of catalogue to accompany an exhibition of the group’s works, but Riopelle objected and insisted on making the launch of the manifesto itself the main event. Borduas thought that its August 9 release date, during school holidays, would lessen any risk of the publication threatening his teaching position at the École du meuble. Unfortunately, the uproar caused by the manifesto’s release could not be ignored and Borduas was let go. However, Refus global proved to be one of the essential factors that led to the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s and the eventual transformation of Quebec society.

Near the end of 1948, the Riopelles returned to Paris. Jean Paul’s first solo exhibition in Paris, Riopelle à La Dragonne (Riopelle at La Dragonne) soon followed. It took place from March 23 to April 23, 1949, at Galerie Nina Dausset, where he showed his inks, watercolours, and oil paintings. Works like City of No Words—The Wood Hive (Cité sans parole—La ruche du bois), 1948, show a colourful background offset by bold applications of ink, characteristic of his work at that time. André Breton, Élisa Breton (1906–2000), and Benjamin Péret (1899–1959), the latter a poet, Dadaist, and Surrealist, created a text about Riopelle for the occasion: “Aparté” (a private conversation) emphasized his “Canadian” character—his accent, the “pearl grey” houses of Gaspésie, the “dark lakes” north of Montreal, and the “great woods.” Breton described Riopelle as a “superior trapper,” a label that long remained attached to him in Paris:

For me, his art is that of a superior trapper. Traps both for the animals of the burrows and for those of the clouds, as [the Symbolist poet] Germain Nouveau said. What I find useful about the notion of a trap, which I like somewhat, is that they are also traps for traps. Once these traps are trapped, a high degree of freedom is achieved.

Véhémences confrontées and the Mosaic Breakthrough

In 1951 the painter Georges Mathieu (1921–2012), leader of the French Lyrical Abstraction movement, organized an international exhibition, Véhémences confrontées (Confronted Vehemences). Its intention was to “confront” the various trends in contemporary art in France, Germany, Italy, and North America. The show included paintings by Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), Willem de Kooning (1904–1997), Giuseppe Capogrossi (1900–1972), Alfred Russell (1920–2007), and Riopelle. As Mathieu later wrote, he “had the handout for the exhibition made in the form of a large manifesto-poster on coated paper with the texts in red on the front and the reproductions of the artworks and the graphics in black on the back.”

For Riopelle, who was already feeling a certain detachment from Breton’s Surrealism, his participation in Véhémences confrontées marked a move toward a body of work that would come to be known as the “mosaics.” Throughout the 1950s, these large paintings, including The Wheel (Cold Dog—Indian Summer) (La roue [Cold Dog—Indian Summer]), 1954–55, would come to make Riopelle’s name and garner him international renown for his abandonment of the brush for the palette knife. The canvases, composed of pure colour straight from the tube applied with a palette knife, have an ethereal quality and resemble the tesserae of a mosaic.

In 1952 Riopelle’s friend Henri Fara lent him his studio on rue Durantin in Montmartre. “This is the first time I’ve had a workshop of my own,” the artist confessed. Having the creative space enabled him to exhibit at the Galerie Pierre Loeb from May 8 to 23, 1953. For Pierre Schneider, this decisive exhibition was the starting point for Riopelle’s Paris celebrity: “Unknown in 1947, exhibiting only in small galleries on the Left Bank, he gained some fame only around 1953, while he was exhibiting at Pierre Loeb’s.”

Riopelle’s increasing fame led Pierre Matisse, the youngest child of the French painter Henri Matisse (1869–1954), to include him in a group exhibition in his New York gallery from October 26 to November 14, 1953, which featured the work of internationally renowned painters such as Balthus (1908–2001), Georges Braque (1882–1863), Constantin Brancusi (1876–1957), Marc Chagall (1887–1985), André Derain (1880–1954), Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985), Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966), Joan Miró (1893–1983), Amadeo Modigliani (1884–1920), and Georges Rouault (1871–1958). Among Riopelle’s works in the exhibition was Tribute to Robert the Evil One (Hommage à Robert le diabolique), 1953, one of his most remarkable mosaics to date. The show was a success and from 1954 onward, Pierre Matisse regularly held solo exhibition of Riopelle’s art in New York, which was significant since a manufactured rivalry between the Paris school of artists and the New York one was under development (and Riopelle was associated with the former); the two men became close friends, sharing an enthusiasm for sailboats and vintage cars.

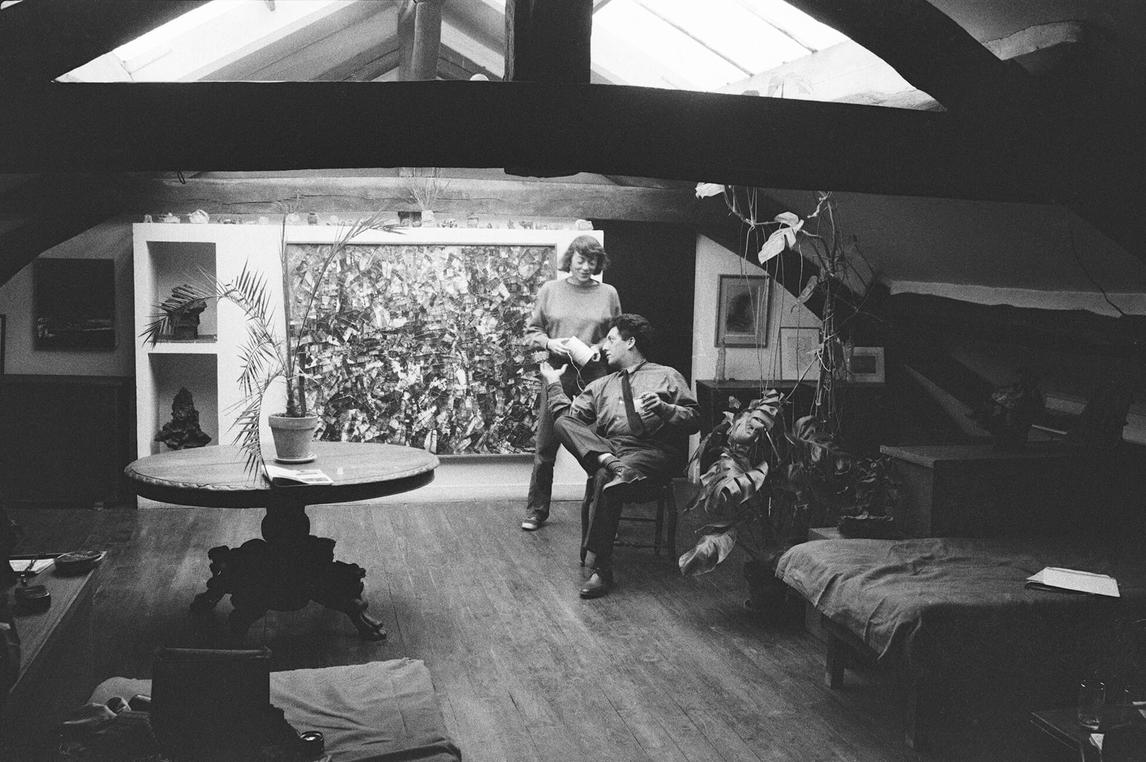

The 1960s and Relationships with Mitchell and Monet

Joan Mitchell (1925–1992), a young painter from Chicago, met Riopelle in Paris in the summer of 1955. (Riopelle and Françoise Lespérance separated a few years later in 1958; they would divorce in 1959). The two quickly became romantic partners and began a relationship that lasted nearly twenty-five years. Riopelle had recently exhibited twice at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York in 1955, the first time in May and the second in December. Mitchell may have seen the second show, as she had returned to America a few weeks after meeting Riopelle and worked at her studio in St. Mark’s Place in New York. The two artists corresponded while apart. In a letter to her dated January 10, 1956, Riopelle confided that being short of inspiration in oils, he was painting in gouache. It is a medium in which he became proficient, as is clear in Eskimo Mask, 1955.

By 1959 Mitchell had settled permanently in Paris, where she lived with Riopelle on rue Frémicourt, in the fifteenth arrondissement. In the summer of 1960, after a brief visit to Long Island and New York City, Riopelle resumed the practice of sculpture. The artist liked to say that he had “always” been sculpting, as evidenced by three small mud-brick figures, dated 1947–48, photographed in the snow by Riopelle himself. On his return to France, he shared a studio in Meudon, southwest of central Paris, with Roseline Granet (b.1936), a French sculptor known for her Tribute to Jean-Paul Sartre (Hommage à Jean-Paul Sartre), 1987, a work commissioned by the City of Paris. Throughout his career, Riopelle created many sculptures to which he said he attached “enormous importance.”

From June 26 to August 23, 1962, Riopelle represented Canada at the 31st Venice Biennale, where his work—paintings and sculptures freshly cast in bronze such as The Tooth at the Opera (La dent à l’opéra), 1960—filled the entire Canada Pavilion. The work earned him the UNESCO Prize, “a distinction that no other Canadian artist had yet won.” At the same Biennale, Alberto Giacometti won the grand prize for sculpture and Alfred Manessier (1911–1993) the prize for painting.

Both Riopelle and Mitchell greatly admired the work of Claude Monet, particularly the large paintings of his pond and garden at Givenchy. Already in 1957, Riopelle had been referred to as an heir to the artist’s work by Life magazine. What they found fascinating was how the works appeared abstract even though they were intended to represent a natural setting. Additionally, the works looked to have neither top nor bottom and could be exhibited any which way. The water, plant life, and their reflections seemed to blend seamlessly into a unified whole.

Riopelle and Mitchell’s mutual interest led them in 1967 to Vétheuil, a village on the Seine about sixty kilometres northwest of Paris, which is where Monet lived from 1878 to 1881. In Vétheuil, Mitchell acquired La Tour, a vast property with a garden where the pair then settled. Riopelle would travel to Paris almost every day, notably to Meudon, where he worked on his sculpture. He also spent time at the Imprimerie Arte–Adrien Maeght, a printmaking atelier. He got into the habit of cutting up his unwanted prints to make collages, sometimes creating ones of impressive size, such as Verb-Herb (Verbe-Herbe) and Sawed Spikes (Épis sciés), both from 1967. With these new works, Riopelle went towards an increasingly fragmented artistic style. Nonetheless, the collages are recognized as some of his most interesting work of the period.

A personal highlight of the decade for Riopelle was his first major exhibition in Quebec, Peintures et sculptures de Riopelle (Paintings and Sculptures by Riopelle), held in the summer of 1967. The exhibition was organized by Guy Viau (1920–1971), who was an associate of the Automatistes and at the time was the director of the Musée du Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec). The exhibition included pieces such as Untitled (Sans titre), 1967, an assemblage donated to the museum by the artist on the occasion of the ambitious retrospective.

The 1970s and the Return Home

In the 1970s Riopelle’s visits to Canada became increasingly longer and more frequent. At the suggestion of his friend Champlain Charest, Riopelle set up a studio in Sainte-Marguerite-du-Lac-Masson in the Quebec Laurentians, in 1974. He had become familiar with the area from hunting and fishing trips over the years with Charest. Riopelle designed the studio space according to plans he had once drawn up at the École du meuble: the building, essentially a large loft able to accommodate his sizable paintings allowed him to work in isolation. His travels in the Quebec wilderness as far north as Abitibi and even to James Bay influenced his art practice. He found an abundance of inspiration in his new surroundings: “The string games, the hunting. Fishing. . . . Making artificial flies: now, that is art.”

In 1969 Riopelle began a major sculpture project: The Joust (La joute). It is a monumental ensemble of thirty figures and was first executed in clay and then in plaster. The plaster version was first exhibited at the Fondation Maeght in Saint-Paul de Vence in the south of France from 1970 to 1971, and again in Paris in 1972, as part of the show Ficelles et autres jeux (Strings and Other Games) presented at the Canadian Cultural Centre and the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris. This exhibition, which included such works as Owl-Shovel (Hibou-pelle), Fish (Poisson), Bear (Ours), and Dog (Chien), confirmed Riopelle’s remarkable talent and creative range. As the critic Michel Dupuy wrote, the artist “drops the brushes to sculpt in plaster, clay, or bronze his animals full of power and humour.” The Joust was cast in bronze in 1974 and installed at Olympic Park for the 1976 Summer Olympic Games in Montreal.

The owl, an important element of The Joust (La joute), soon became a recurring motif in Riopelle’s art. From 1970 alone there are more than twenty paintings and almost as many bronze sculptures dedicated to the nocturnal bird. While the works show an incredible variety of representation, they also signify Riopelle’s return to figuration, a trend that had begun in 1965. Some considered this abandonment of pure abstraction by the painter as an affront; however, Riopelle did not consider abstract and figural work to be separate from one another. As he explained:

Those of my paintings considered the most abstract have been, for me, the most figurative, in the true sense of the word. On the other hand, geese, owls, moose. . . . These paintings whose meaning we think we can read—aren’t they even more abstract than the rest? Abstract: “abstraction,” “drawing from,” “taking from. . .” My approach is the opposite. I don’t draw from nature, I go toward nature. . . . To be honest, abstraction doesn’t exist in painting. Abstraction is impossible; figuration is just as impossible. Paint the sky?. . . One could risk it, but only if one has never seen the sky. In this sense, as I have already said, I am less impressionist than depressionist. I move just the right distance away from reality, but I don’t totally separate myself from it. How much distance do I establish? The right amount.

Beginning in 1976 large snow geese were added to Riopelle’s repertoire, such as in The Lachange Brothers (Les frères Lachance) from 1983. He became fascinated by their annual migration, when more than seventy-five-thousands of them would invade Cap Tourmente, just north of Quebec City. The experience affected Riopelle so deeply that he would often return to it in his later work, including in a series of thirteen lithographs on Japanese paper from 1983.

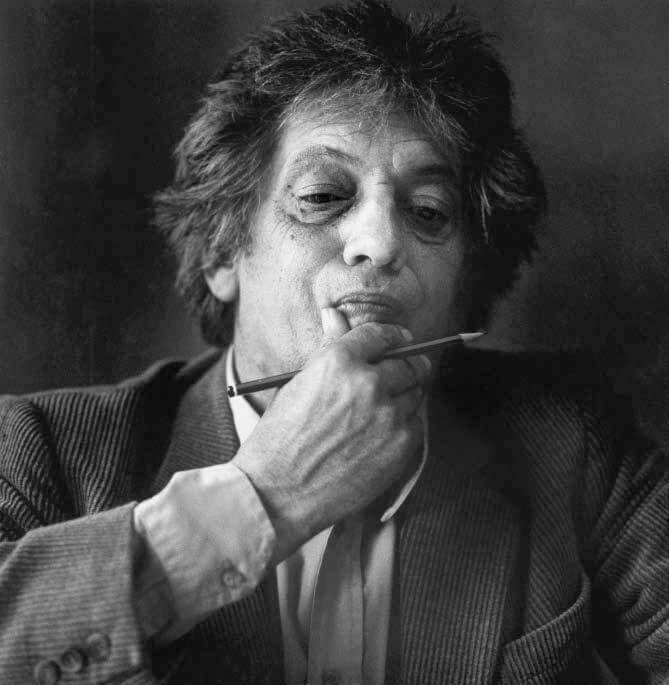

The 1980s and Recognition

In the 1980s numerous Canadian retrospective exhibitions devoted to the art of the Automatistes took place, including Riopelle: La Révolution automatiste, organized by the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal in 1980 and L’Étoile noire (Black Star), a 1981 travelling exhibition organized in collaboration with the Art Gallery of Peterborough, Ontario, the National Gallery of Canada, the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, and the Musée du Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec). Galerie Dresdnere in Toronto mounted two shows, Les Automatistes d’hier à aujourd’hui / The Automatistes Then and Now in 1986 and Borduas and Other Rebels in 1988; and the Drabinsky Gallery, also in Toronto, showed in 1990 Les Automatistes: Montreal Painting of the 1940s and 1950s. Finally, the Musée de Saint-Hilaire (now Musée des beaux-arts de Saint-Hilaire), Quebec, presented Saint-Hilaire et les Automatistes in 1997. These events showcased Riopelle’s work, which was seen as central to the Automatistes’ rejection of the cultural and political status quo in Quebec in the 1940s.

In the same period, Riopelle was also honoured in France: in 1981 the Musée national d’art moderne de Paris organized a retrospective of his work from 1946 to 1977. This exhibition travelled to the Musée du Québec, the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City, and finally the Galería de Arte Nacional in Caracas. In 1981 the Prix Paul-Émile-Borduas, Quebec’s most prestigious award for an artist, was presented to Riopelle in recognition of his major contribution to cultural life.

Soon after these accolades Riopelle returned to his first remote studio, the one he built in 1974 at Sainte-Marguerite-du-Lac-Masson in the Laurentians. Before long he travelled to Île-aux-Oies (island of geese) and Isle-aux-Grues (island of cranes), two islands connected by a sandbar that are part of an archipelago in the Saint Lawrence River northeast of Quebec City. Riopelle had frequented the area since 1974 as a member of a hunting club and in 1976 undertook a series of drawings documenting the area. A work like Blue Geese (Les oies bleues), 1981, details the natural panoramas that surrounded Riopelle as he lived alternately in the Laurentians and Isle-aux-Grues after his permanent return from France in 1990. It was on the windy Île-aux-Oies where the artist set up a new studio in the former town hall—an old farm house called Le Repaire (the lair). There he produced many of his works from 1990 and 1992.

A Final Tribute and Last Years

Joan Mitchell died on October 30, 1992, in the American Hospital of Paris, Neuilly-sur-Seine. Although the couple had separated in 1979, when Riopelle returned to Île-aux-Oies that fall, he began his last great monumental painting, Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg (Hommage à Rosa Luxemburg), 1992, in memory of their shared life. The work, more than forty metres long and comprising thirty paintings, was first exhibited in Mont-Rolland in the Laurentians in April 1993. For five days nearly a hundred visitors admired the piece. It was shown in the fall of the same year in a Montreal gallery, Michel Tétreault Art International, under the title Œuvres vives et l’Hommage à Rosa Luxemburg (Œuvres vives and the Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg). The three sections were arranged in a U shape so viewers literally had to enter the work to see it. It then travelled in 1995 to the Château de La Roche-Guyon, not far from Paris, and on to the Musée du Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec [MNBAQ]) in the spring of 1996, where, over a five-week period, thirty-three thousand visitors were able to see it.

Following an agreement with Loto-Québec, the work was acquired in 1996 as a gift from Riopelle to the Musée du Québec, together with two other major works by the artist, Pangnirtung, 1977, and Victory and the Sphinx (La victoire et le sphinx), 1963. Tribute was to be hung in the Casino de Hull (now the Casino du Lac-Leamy) for twenty years but spent only three years there before being moved to the Musée du Québec in May 2000 to ensure its preservation. Thanks to the diligence of John R. Porter, then director of the museum, the work was retrieved and exhibited in two ways: its three sections were first presented in a Z shape, then reorganized as they can be seen today, along a corridor in the new Pierre Lassonde Pavilion of the MNBAQ.

Riopelle’s last works, such as The Happy Isle (L’Isle heureuse), 1992, a luminous large-format painting on wood, radiate the serenity of the later years of a worldly painter who chose for his final destination a tranquil retreat into the natural environment he loved. Having been made a Grand Officer of the National Order of Quebec in 1994, he was recognized both at home and abroad as one of the great artists of his generation. Jean Paul Riopelle died at his home on Île-aux-Grues on March 12, 2002. On March 18, the government of Quebec, at the behest of the Parti Québécois premier Bernard Landry, held a national funeral in his honour.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements