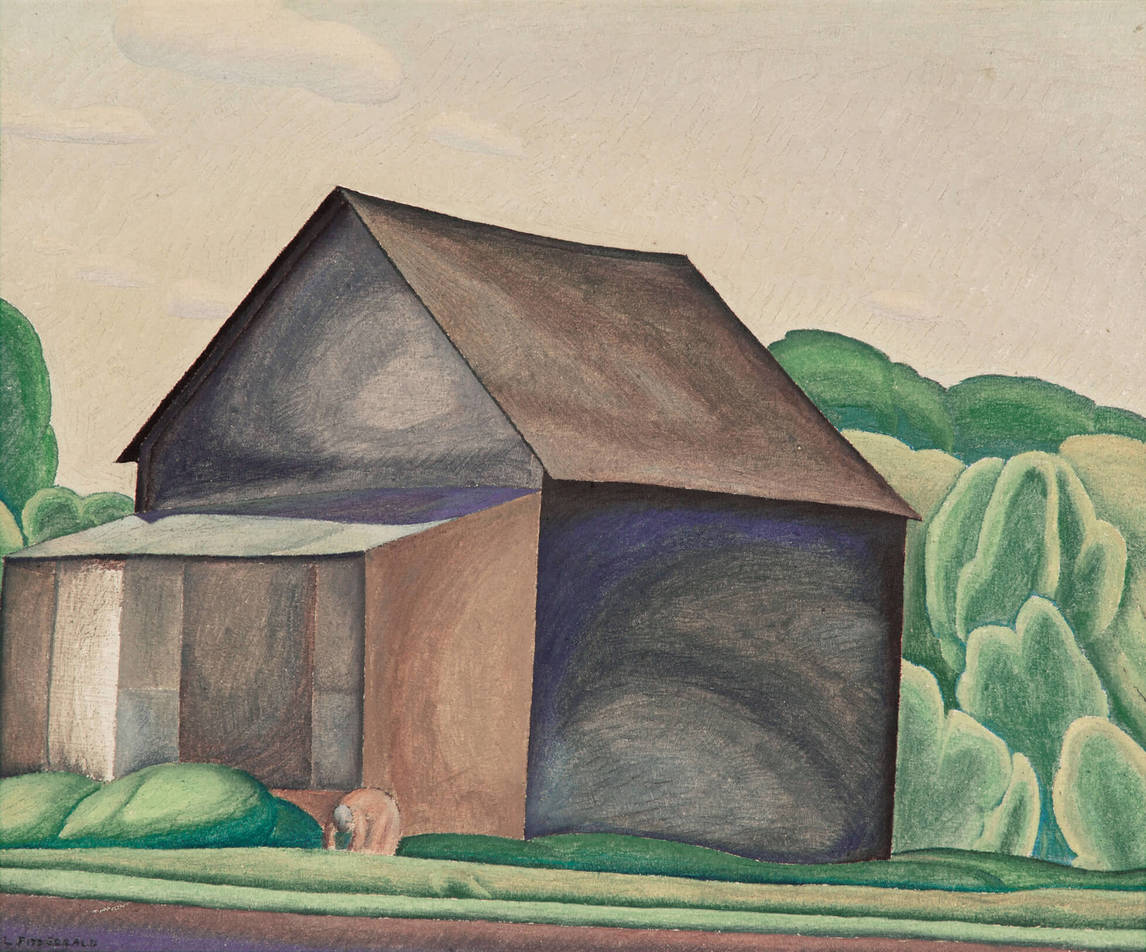

Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald’s work has come to epitomize the prairie landscape experience. He is the artist who perfected the quintessential Western Canadian look of land, sky, trees, and, most importantly, the penetrating, intense light. This led him to be invited by the Group of Seven to become their tenth member. While capturing the essence of place, FitzGerald’s art transcends subject matter and empirical observation, addressing formal problems and universal issues that still resonate beyond the borders of his native home.

The Formation of an Aesthetic

By the early 1930s FitzGerald had achieved maturity as an artist, a fact signalled by his most important painting, Doc Snyder’s House, 1931. The Group of Seven recognized his mastery and perceived FitzGerald as a kindred spirit. In May 1932 Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), acting on the group’s behalf, invited FitzGerald to become an official member. He was pleased to accept this recognition as the only Western Canadian artist to join their ranks, although his direct association with them was to be short-lived. The group disbanded by early 1933 to form the larger exhibiting society the Canadian Group of Painters (CGP), which included FitzGerald as a founding member. At the first CGP exhibition held during the summer of 1933 in Atlantic City, New Jersey, FitzGerald exhibited Broken Tree in Landscape, 1931, under the title Dead Tree.

Although he sensed a “definite connection” to the Group of Seven, FitzGerald’s aims were quite different. He did not feel compelled to express their aggressive brand of Canadian national identity through his art nor to seek out sublime views of Canada’s vast wilderness as source material for his work. On the contrary, his was a veiled approach to Canadian consciousness communicated simply by depicting the immediate Winnipeg prairie and urban surroundings that he loved. Toronto artist Bertram Brooker (1888–1955) recognized how FitzGerald was different. Rather than paying attention to “the essential moods of the country … [he] is constantly searching for the structure, spatial relationships and colour subtleties of the subjects he approaches.”

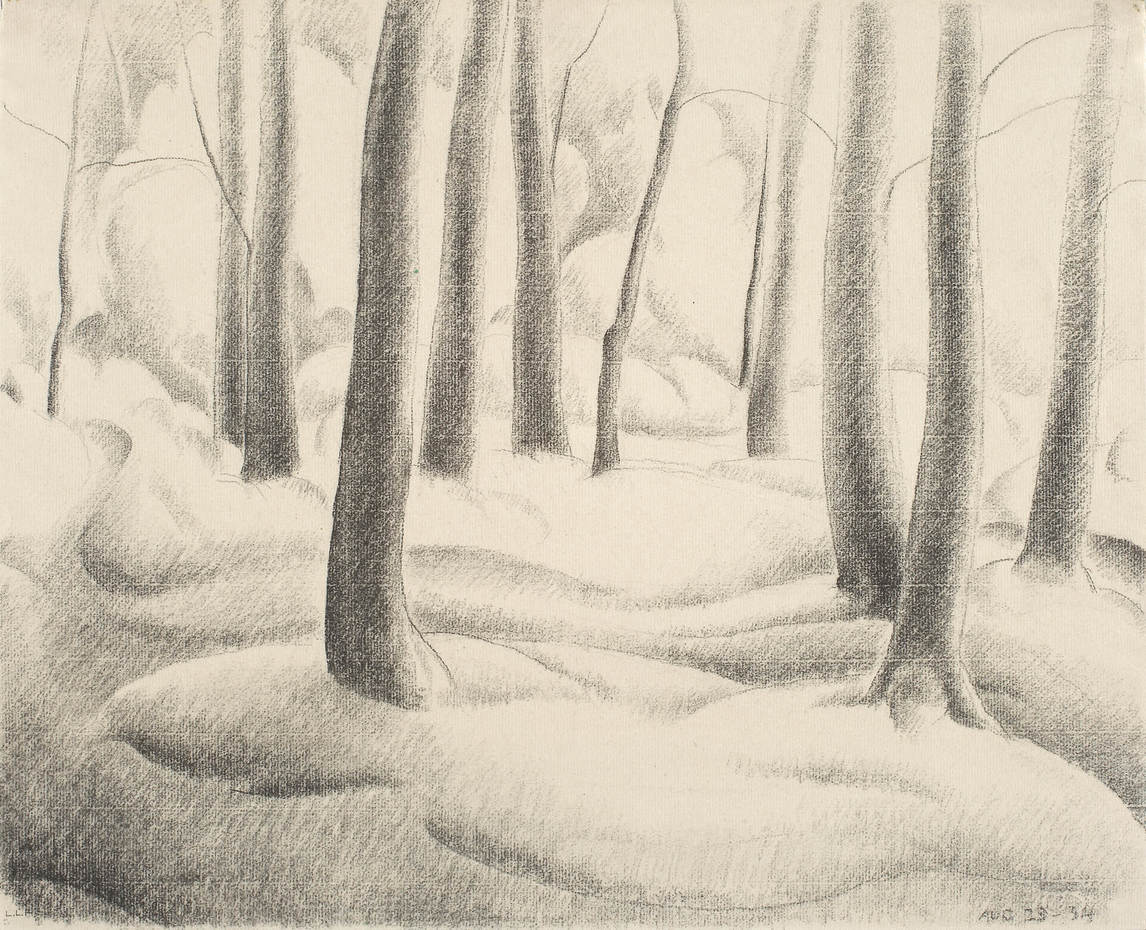

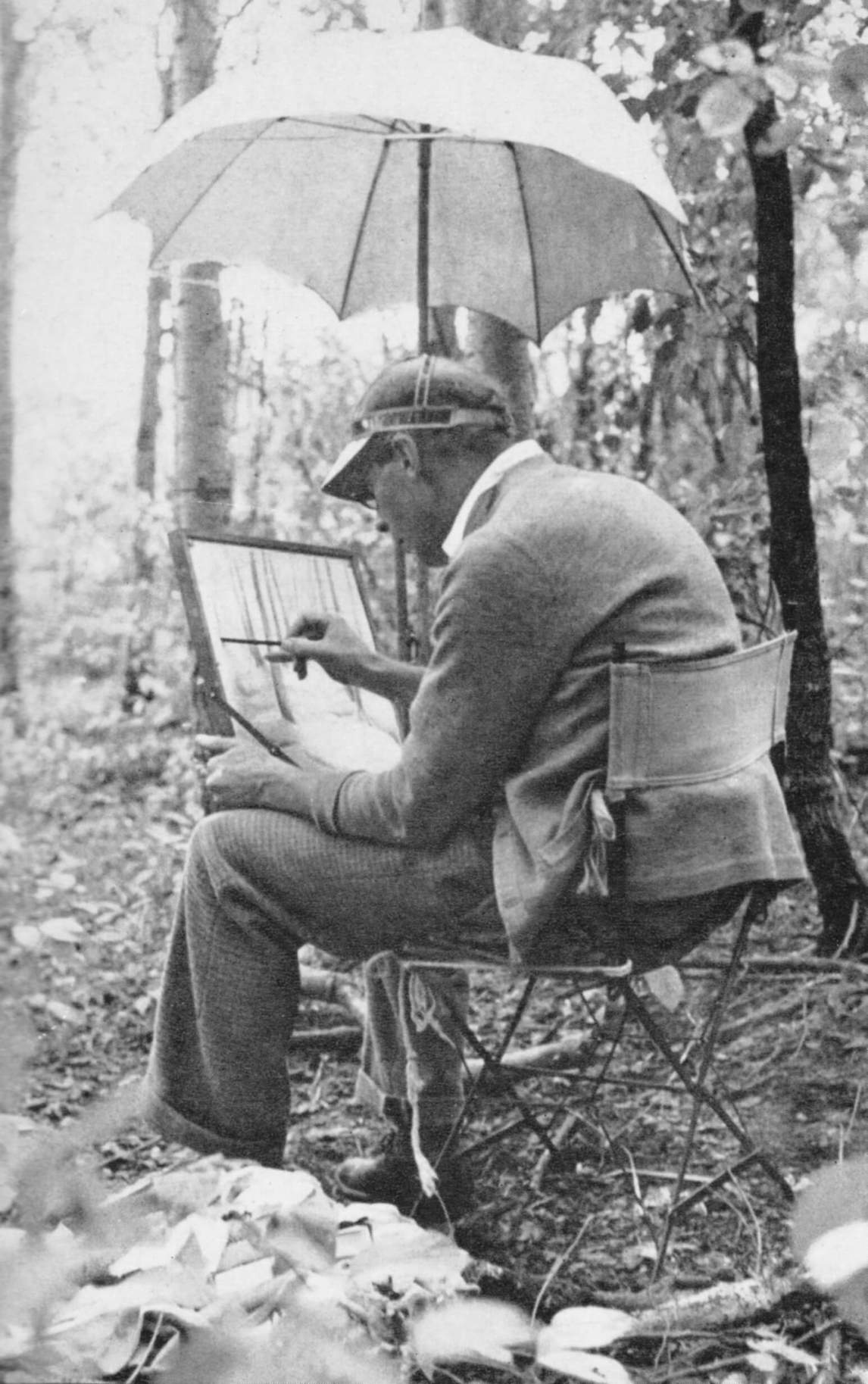

Elements of Drawing (1857) by John Ruskin (1819–1900) was FitzGerald’s initial guide to the close examination of nature that would inform his entire career. Ruskin’s lessons instilled in the young artist the practice of careful empirical observation followed by patient sketching from nature. This is documented in a 1934 photograph of FitzGerald executing a charcoal drawing Landscape with Trees, August 23, 1934, in the Winnipeg neighbourhood of Silver Heights. By the late 1920s, FitzGerald had established an aesthetic position beyond Ruskin’s starting point. Brooker tried to characterize this when describing FitzGerald to Group of Seven–member Lawren Harris (1885–1970): “He seems to have little, if any, interest in metaphysics, but draws his sustenance from the ground and from his recognition of the relationships between all varieties of form—particularly the structure and rhythm in men and trees.” For Brooker, FitzGerald’s genius resided in moving beyond the appearance of nature to explore its underlying meanings.

The pattern of FitzGerald’s career follows a well-travelled route associated since the turn of the twentieth century with European modern artists who used nature as a springboard to explore how line, colour, and form can work together independently. The evolution from recognizable subject matter to abstraction that may be traced in FitzGerald’s work also defined the modernist practice of many avant-garde European twentieth-century artists, including Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), and Kazimir Malevich (1878–1935). But the difference between these artists and FitzGerald is that while some of his late works may look non-objective, they are still rooted ultimately in natural phenomena.

The Living Force

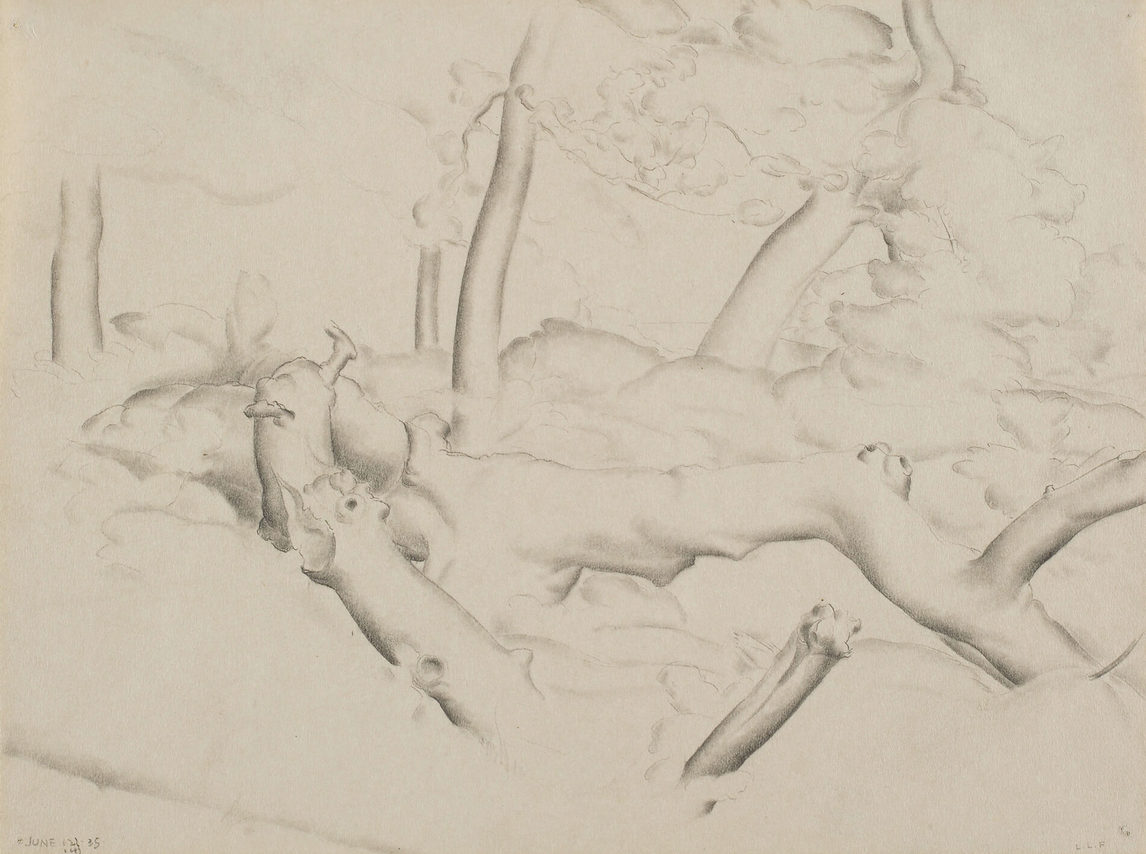

Bertram Brooker immediately seized on the notion of the living quality in FitzGerald’s work when he first acquired a pencil sketch from the artist’s 1928 exhibition at the Arts and Letters Club of Toronto. Presumably he is referring to this drawing in his 1949 lecture: “[I]t was a very fast drawing of a bulbous, twisted tree. Looking at it often I came to think that the tree might just as well be a carrot or an elephant—in other words it was not so much an object as an attempt to search out the organization of any living thing. It was not really a thing, it was a verb—a picture of living!” While this work has not been identified, Trees and Stumps, June 12, 1935, represents the kind of drawing that Brooker described.

The possible sources of FitzGerald’s aesthetics are open to conjecture. Born in 1890 FitzGerald was heir to ideas engendered by two powerful artistic developments from the nineteenth century: the Arts and Crafts movement and Art Nouveau. As an avid reader of the London-based The Studio magazine, he would have been aware of their basic principles. He valued the anti-industrial ethos promulgated by the members of the Arts and Crafts movement, who advocated handmade artistic expressions using a wide variety of media. Art Nouveau, in which architecture and sculptural forms could be transformed into seemingly living, growing plant forms, would have appealed to FitzGerald’s belief that nature was animated by a vital, living force. “The seeing of a tree, a cloud, an earth form always gives me a greater feeling of life than the human body. I really sense the life in the former, and only occasionally in the latter. I rarely feel so free in social intercourse with humans as I always feel with trees.”

The intellectual backdrop for this may have been European neo-Romantic theories about science and aesthetics from the turn of the century, now referred to as Biocentrism, which posits the “idea of ‘nature’ as the experience of the unity of all life.” Blending metaphysics and natural science, Biocentrism influenced the development of various aspects of avant-garde modern art whereby some Russian artists, for example, could see the visible world and the forces of the cosmos linked in mystical and spiritual ways. Bertram Brooker scholar Adam Lauder has pointed to the likely interest shared by FitzGerald and Brooker in biological themes and the doctrine of vitalism (élan vital) (one aspect of the complex amalgam of philosophical beliefs that formed Biocentrism) as an avenue thus far unexplored in scholarship on the two artists.

FitzGerald never mentioned vitalism in his writings, but this anti-mechanistic view of the world would have appealed to both artists and may have been a topic of discussion. A comparison of Tree (with Human Limbs), n.d., by FitzGerald and Shore Roots, 1936, by Brooker demonstrates a shared stylistic and aesthetic sensibility. Brooker owned the book Creative Evolution (1907) by the French philosopher Henri Bergson, who originated the term “élan vital” and whose ideas on the nature of the universe Brooker may have communicated to FitzGerald.

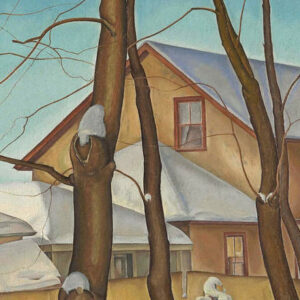

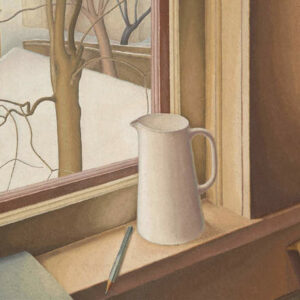

FitzGerald’s intense devotion to capturing the world he saw around him is not unlike that of Jack Chambers (1931–1978), who would much later articulate a theory of “perceptual realism.” Both artists wished to convey a heightened sense of what it means to look at the ordinary elements of one’s surroundings, whether it be a landscape, backyard, or objects on a windowsill. And each artist gave special emphasis to light as an essential component of perception. It is FitzGerald’s genius at representing the prairie light—moving away from the blending effects of atmospheric light in his early Impressionist-inspired works such as Figure in the Woods, 1920, to a light that isolates “compositional elements … stressing their formal relationships” in a mature work such as At Silver Heights, 1931—that sets him apart from any other artist of his generation.

FitzGerald did not publicly or privately align himself with any scientific, religious, or philosophical position, which suggests that his views on art and nature were not codified but rather evolved over time in accordance with what he thought it meant to be an artist. He left behind a considerable amount of writing on that subject in letters, diaries, reports, and talks (all unpublished during his lifetime). The advice he gave to his students at the Winnipeg School of Art, recorded in notes from a lecture possibly given in 1933, articulates his artistic credo: “It is necessary to get inside the object and push it out rather than merely building it up from the outer aspect. So appreciate its structure and living quality rather than the surface only. Through this way of looking at a thing elimination takes place and only the essential things appear.”

FitzGerald often used the words “unity” and “harmony” to describe what he saw in both nature and works of art. He continued in the notes to encourage his students to seek endlessly and contemplate the object’s “place in the universe.” The goal was to gain “an appreciation for the endlessness of the living force which seems to pervade and flow through all natural forms even though they seem on the surface to be so ephemeral.”

Winnipeg’s Artistic Milieu

In comparison with Toronto, Winnipeg was a remote artistic outpost for most of FitzGerald’s career. Yet the place attracted numerous serious artists who came and went with the ebb and flow of employment opportunities. Mutual influence between artists can operate not only in terms of stylistic or philosophic affinities but also in more subtle ways, such as with regard to what it means to be an artist in attitude and practice. FitzGerald no doubt learned from his contemporaries, but what evidence is there for direct artistic influence from those who also drew and painted the prairies, other than the obvious compositional device of low horizon/big sky?

Frank H. Johnston (1888–1949), a member of the Group of Seven, was principal at the Winnipeg School of Art from 1921 to 1924. During this period, he painted Serenity, Lake of the Woods, 1922. Although FitzGerald was studying in New York during part of Johnston’s tenure in Winnipeg, he would have looked to the more established artist as a model for his career. W.J. Phillips (1884–1963), who is known principally for his British-influenced colour woodblock prints and watercolours, was in Winnipeg from 1913 until 1940. He wrote perceptively about FitzGerald’s work, although the two artists were not deep friends. On the other hand, FitzGerald enjoyed the company of Charles Comfort (1900–1994), who worked in Winnipeg for the commercial art firm Brigdens of Winnipeg Limited and attended classes at both the Winnipeg School of Art and then the Art Students League of New York from 1922 to 1923 (just after FitzGerald). The glowing colours of Prairie Road, 1925, suggest that the prairie is a place of mystic wonder for Comfort—a sensibility he shared with FitzGerald but, as can be seen in The Prairie, 1929, expressed in different terms.

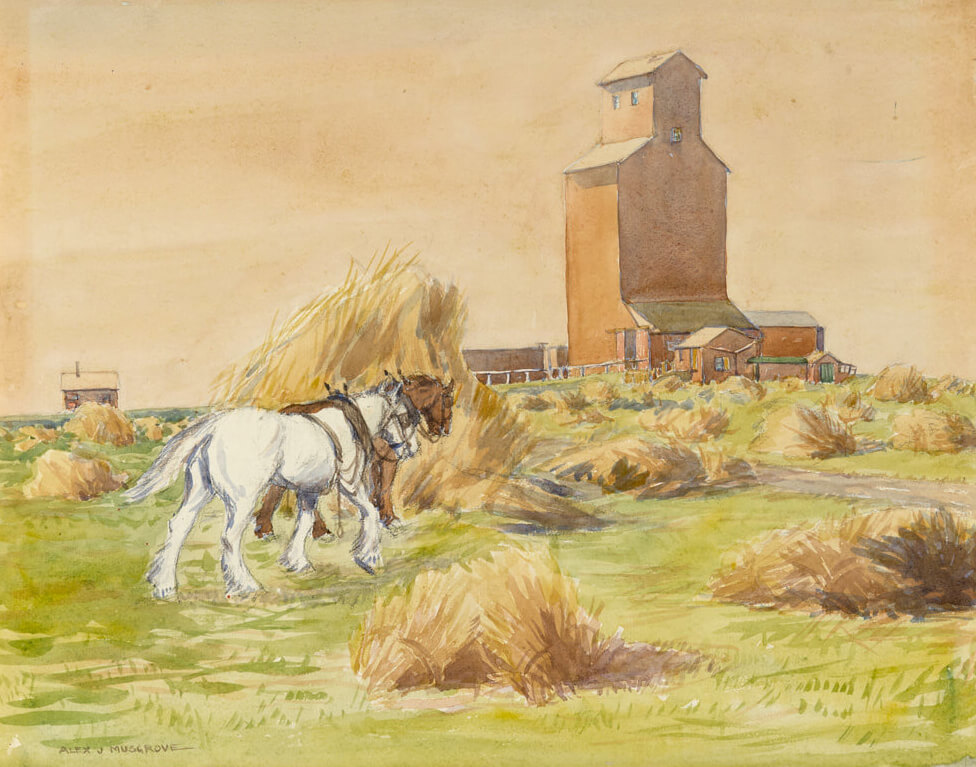

The German-born Fritz Brandtner (1896–1969), who arrived in Winnipeg in 1928 and left in 1934, was an exponent of German Expressionism. It is likely that he spoke with FitzGerald about the latest European developments in Expressionism, Constructivism, and the Bauhaus. Another German émigré, Eric Bergman (1893–1958), arrived in Winnipeg in 1914 to find employment at Brigdens of Winnipeg Limited. Like W.J. Phillips, Bergman excelled at woodblock printmaking, as did other Winnipeg contemporaries such as Alison Newton (1890–1967) and Alexander Musgrove (1882–1952).

Musgrove was principal at the Winnipeg School of Art from 1913 until 1921. Although he was a practitioner of “conservative” realism—for example, Country Elevator with Horses and Field of Hay, c. 1920–29—his energy as a tireless advocate for the arts (he founded the Winnipeg Sketch Club in 1914 and co-founded the Manitoba Society of Artists in 1925) would have impressed FitzGerald.

Given his association with the aforementioned artists, FitzGerald’s isolation in Winnipeg was only one of degree. Nevertheless, art historian Liz Wylie is correct in concluding that in the works of his contemporaries, “one may see some stylistic similarity to FitzGerald’s prairie paintings, but any such parallel is usually a fairly superficial one.”

Teaching and Legacy

FitzGerald taught at the Winnipeg School of Art from 1924 until 1947. During that period he came in contact with hundreds of students. A few went on to enjoy professional art careers of consequence. While FitzGerald did not encourage disciples of his work, he exerted a powerful influence remembered years later.

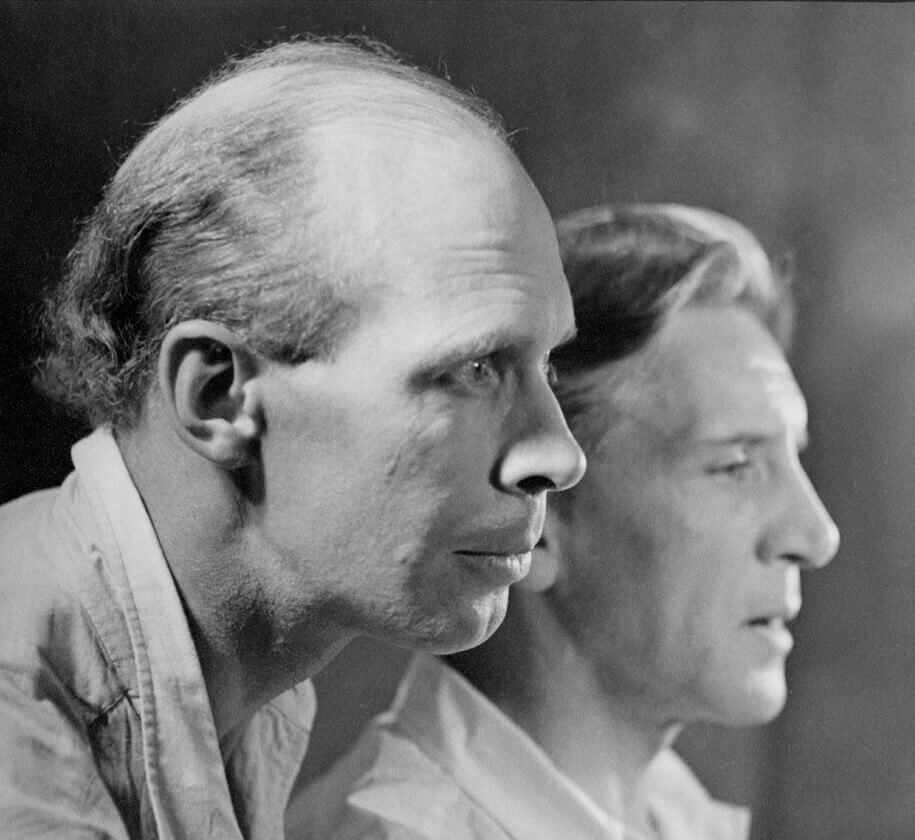

Caven Atkins (1907–2000), who was a student and later an instructor at the school from 1930 to 1934, recalled the nine-year period in which he knew FitzGerald. Atkins stressed that FitzGerald “tried to fire the students’ imagination to observe and through trial and error, find their own methods to achieve ‘their’ feelings.” Perhaps influenced stylistically by FitzGerald more than any of his contemporaries, Atkins’s drawings, linocut prints, and a number of paintings clearly reflect an affinity in terms of composition, although his oils are more strident in hue and tone than FitzGerald’s delicate handling of paint. This is evident in a comparison of Atkins’s Landscape with River, Beausejour, Manitoba, 1937, with FitzGerald’s painting Summer, 1931.

Gordon Smith (b. 1919), who became a noted abstract artist from British Columbia, studied drawing under FitzGerald at the school from 1935 to 1936. In an interview, Smith pointed out that FitzGerald advocated a very close observation of the subject to be sketched before beginning a contour line that would later be filled in. “He’d talk about a keen line and he’d say, start at the top, around the head and make that line go around and watch your eye the way a fly crawls over your shoulder and really search and draw with your eye.”

FitzGerald often made reference in his writings to the importance of the artist keeping the eye of the viewer within the composition of a picture. Irene Heywood Hemsworth (1912–1989) was a student of FitzGerald from 1931 to 1934. She remembers: “The square, the edge of a painting was terribly important to him…. He had to have an inside pencil line before he started. Every piece of that square was important to him.”

FitzGerald’s former students recalled his character with great fondness. Atkins remembered: “He was a very earthy man. He loved nature and simple things. He was philosophic, but in a simple, not a complex form or way. He would have made a very good Zen monk.” Smith remarked on FitzGerald’s mere presence as an example to students of what it was to be a professional artist: “I think he taught you to think.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements