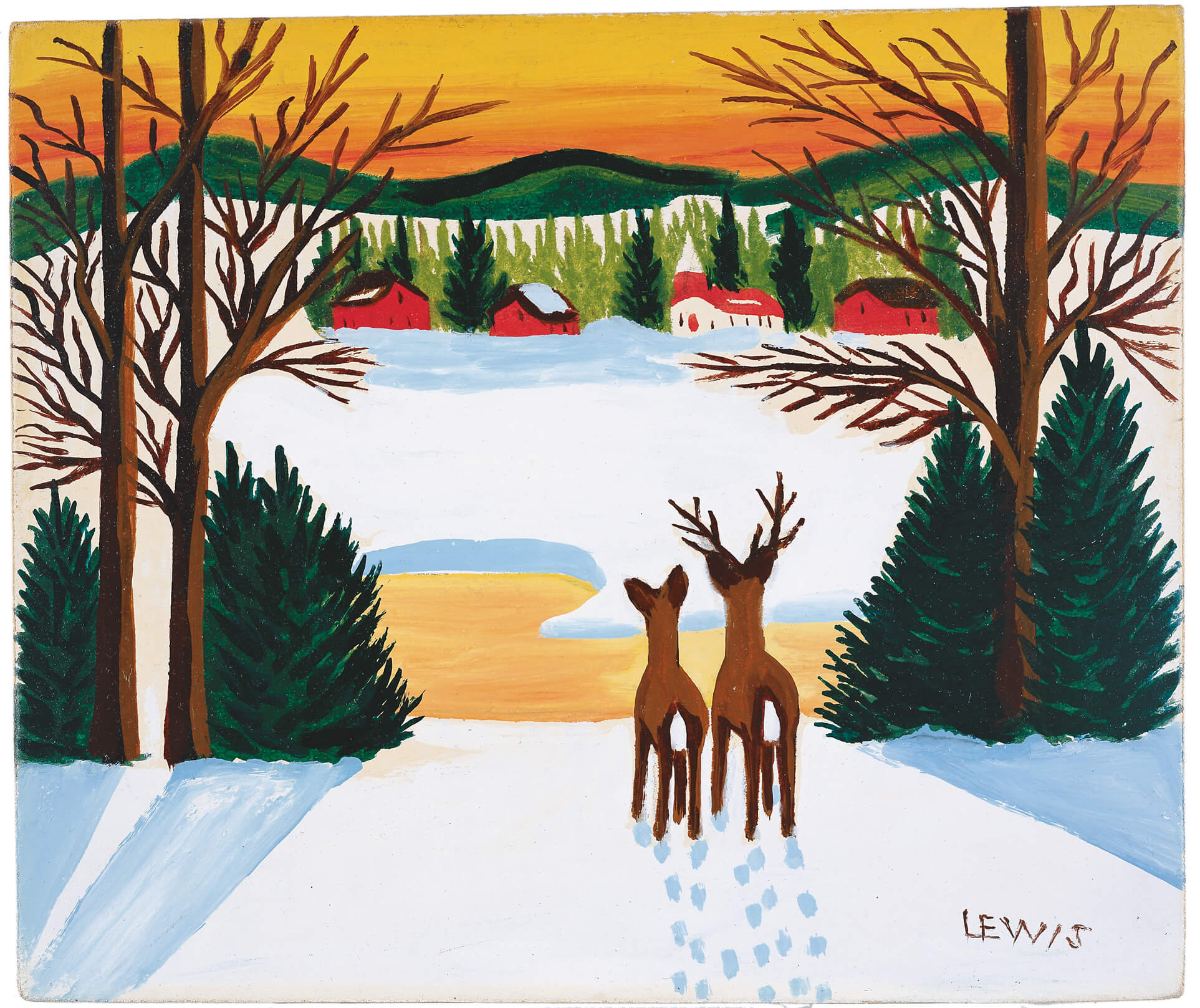

Deer in Winter c.1950

Maud Lewis, Deer in Winter, c.1950

Oil on pulpboard, 29.6 x 35.9 cm

Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax

This relatively early Maud Lewis image of two deer looking across a valley at a small village has many elements that became notable in her style. These include a sense of contained space—the viewer’s eye is led from the foreground through the entire composition until it is stopped by the line of hills in the background. The painting is also notable for its treatment of light. Despite being characterized as “without shadows,” her work often did, in fact, have shadows. Here they are clearly visible, cast by objects lit by the variegated light of the setting (or rising) sun. The three hills are shadowed at their crests. The trees in the foreground cast blue shadows on the snow, as do the stand of trees and the buildings in the middle ground. The three leafless hardwood trees also display shadows on their trunks. The pond (or stream) in the middle ground is shadowed by snowbanks and reflects the orange of the sun.

The Nova Scotia Lewis depicts is a rosy version of its past and her work is essentially nostalgic. Here the tiny village—a few houses and barns flanking a white wooden church—lies nestled in its peaceful valley. There are no signs of modernity—no power lines or even a road. The unlikely pair of white tail deer—a doe and a stag—look out onto the scene much as the viewer of the painting does. Here we have nature observing culture, a bucolic and wishful expression of harmony between the human and animal worlds.

Lewis often painted deer in scenes that are reminiscent of illustrations from calendars depicting hunting scenes, such as the leaping stag in Deer Crossing Stream, 1960s. That sense of action is absent in this painting, where the image shares a certain romanticism with many of her village scenes.

The deer are framed by the trees at their sides, which overarch them in what, in another season, would have been a sort of bower. The internal frame is a common compositional element employed by Lewis in her paintings of oxen and cats, which are often shown surrounded by floral borders. Here the scene is framed like a stage set, with the deer serving as actors or audience, depending on our point of view. This device is a common graphic technique, used to this day in advertising and calendar imagery, to focus the eye on the central figures. Lewis’s adoption of it, and her use of natural elements to create the framing effect, highlight how she absorbed the lessons of the graphic work she saw in magazines and other sources, mining them to create her own visual strategies.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements