Barry Ace

Barry Ace, trinity suite: Bandolier for Niibwa Ndanwendaagan (My Relatives); Bandolier for Manidoo-minising (Manitoulin Island); Bandolier for Charlie (In Memoriam), 2011-2015

Mixed media (motion sensor display monitors, fabric, metal, horsehair, extension cords, mirror, plastic, capacitors and resistors), overall installed: 207 x 95 x 53 cm

Collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

The above image depicts a 2018 installation of the work at the McLean Centre, Art Gallery of Ontario.

Anishinābe artist Barry Ace (b.1958) draws inspiration for his art practice from the historical Anishinaabeg arts of the Great Lakes region. His mixed-media works upcycle reclaimed and salvaged electronic components including capacitors and resistors, transforming the refuse of our technological age into complex beadwork-inspired floral motifs. Ace’s trinity suite: Bandolier for Niibwa Ndanwendaagan (My Relatives); Bandolier for Manidoo-minising (Manitoulin Island); Bandolier for Charlie (In Memoriam), 2011–2015, reveals his deep exploration of manidoominens, spirit berries, and electronic components. As he explains, his “work embraces the impact of the digital age and how it exponentially transforms and infuses Anishinaabeg culture (and other global cultures) with new technologies and new ways of communicating, harnessing, and bridging the precipice between historical and contemporary knowledge, art, and power, while maintaining a distinct Anishinaabeg aesthetic connecting generations.”

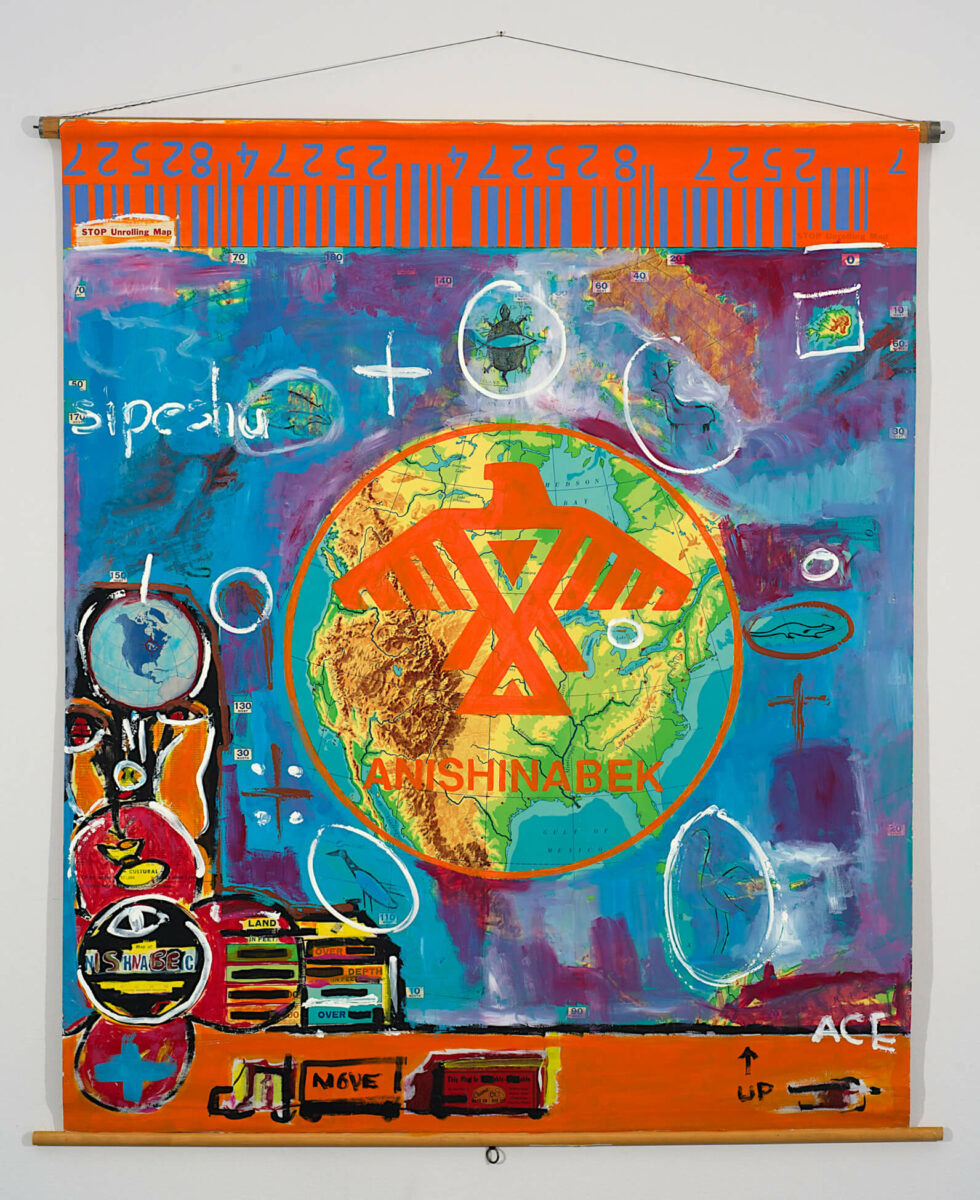

Ace is Odawa and a debendaagzijig (citizen) of the M’Chigeeng First Nation, Odawa Mnis (Manitoulin Island, Ontario). He learned Indigenous techniques at an early age, inspired by Anishinābe beadwork, quillwork, and basketry. After initially studying electronic engineering at Cambrian College in Sudbury, he switched to graphic arts. Still, his knowledge of circuitry has played a role in his art, especially in the mixed-media works that include electrical components. In everything that he creates, Ace affirms the need to take control of imagery and representation and assert one’s identity and culture. In Anishinabek in the Hood, 2007, for instance, he created a work in which his Indigenous self has re-established his place in the Eurocentric world of mapping, and reversed the concepts of dispossession and relocation that the maps represent.

From 1994 to 2000, Ace was chief curator at the federal Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (now called Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada). In that time, he was responsible for numerous exhibitions, including Transitions: Contemporary Canadian Indian and Inuit Art (1997), which toured internationally. In 2006, Ace co-founded and served as the inaugural director of the Aboriginal Curatorial Collective (now the Indigenous Curatorial Collective). He later became one of the founding members of the Ottawa-based artist collective Ottawa Ontario Seven (OO7), which supports Indigenous artists with opportunities for self-curation, public engagement, and critique.

Ace’s work also extends to include collaborative projects, as in his recent work for the exhibition wāwīndamaw, promise: Indigenous Art and Colonial Treaties in Canada at the North American Native Museum in Zurich, Switzerland. Ace created a site-specific collaborative work that is an extension of his 2018 collaborative work For as long as the sun shines, grass grows and water flows that coalesced the complex Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action in response to the adverse impact of Canada’s residential institutions calling for reconciliation between Canadians and Indigenous peoples. The work waawiindmawaa – promise (to promise something to somebody), 2022, focuses attention on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and also fulfills the Truth and Reconciliation Call to Action #83 (“for Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists to undertake collaborative projects and produce works that contribute to the reconciliation process”) and takes the call to an international level.

Ace’s body of work is a constant reminder that Indigenous art is not in stasis. His constantly evolving artistic practice manifests the reality that Indigenous practitioners are continuously striving to represent and explore their own social, political, environmental, and cultural context within a larger negotiated space.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements