While she was a student and an apprentice, Lake’s experience in art was in drawing, printmaking, and abstract painting. Once she purchased a camera, she became interested in the interplay between a performance (usually by herself) and the viewer’s perception of it, and in the way photographic devices could make this connection visible. Her physical manipulations of film through stretching and lighting reveal hidden aspects of the subject’s inner self, even as her constant use of her own body provides a visual marker through which to consider the mechanical techniques of photography.

Camera Art

Lake took up photography in 1970 to “see what [she] looked like” as she engaged in various performances and to convey her experience in a manner the audience could trust.1 She called the results “camera art,” a term coined by video artist Les Levine (b.1935), who described it as “devoid of logic,” requiring viewers to apply their own reasoning to it. Beyond an emphasis on narrative content, Lake’s photographs hinge on aesthetic and compositional concerns and on attention to the process of creating the works themselves. For this reason, Lake’s oeuvre has often been considered part of the Conceptual art movement: her photography explores not only social and perceptual processes but also the medium itself. Lake’s own body became—and has remained—the primary site of exploration.

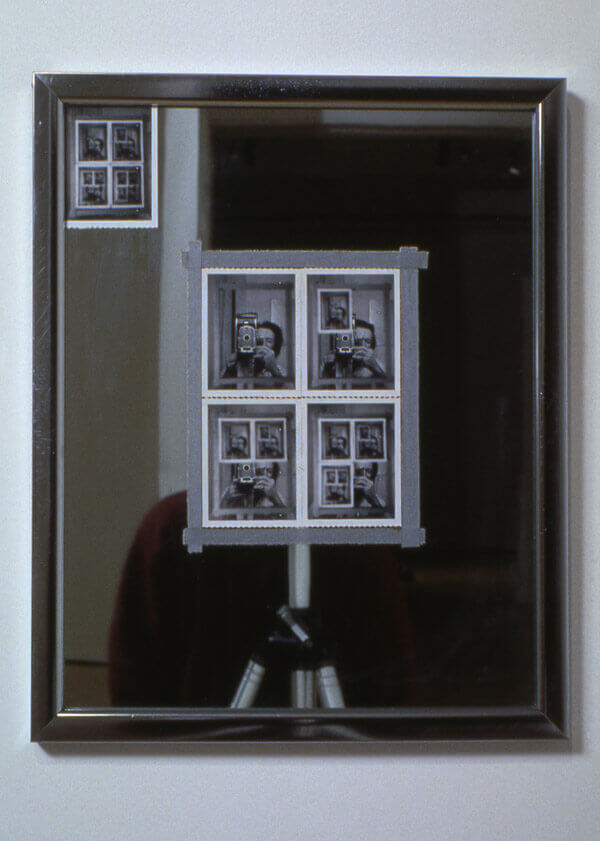

Photography as employed within Conceptualism offered the means through which to document conceptual experiments, at once acting as a document and as a work itself. Process, duration, and action were crystallized into an image, or images, whereby artists employed organizational structures, such as the grid, to communicate the different stages of their experiments as they unfold through time. A notable example is Nine Polaroid Photographs of a Mirror, 1967, by American artist William Anastasi (b.1933)—a grid-within-a-grid work composed of nine larger photographic images of the artist taking his own picture in front of a mirror. The camera is also reflected in the mirror, seemingly pointed directly at the viewer. Anastasi takes his portrait, and the immediacy offered by the Polaroid format allows him to affix the fresh image to the mirror, creating a grid on the mirror until almost its entire surface is covered, save for the bottom-right corner, where his forearm remains visible. Within the new grid, an even smaller grid begins to appear—the document of Anastasi’s placement of each new photograph onto the mirror. Two years later, Canadian artist Michael Snow (b.1928) would engage a similar experiment with Authorization, 1969, covering only part of the mirror’s surface to produce a grid of four images and one stray photograph in the top-left corner. Photography, here, is at once the end product and a record of the product’s making. Lake frequently used a grid format for displaying her photographs and constructing a narrative. This arrangement further emphasizes notions of duration and process—the ability to document a performance or event over time as well as the steps taken in making the works themselves.

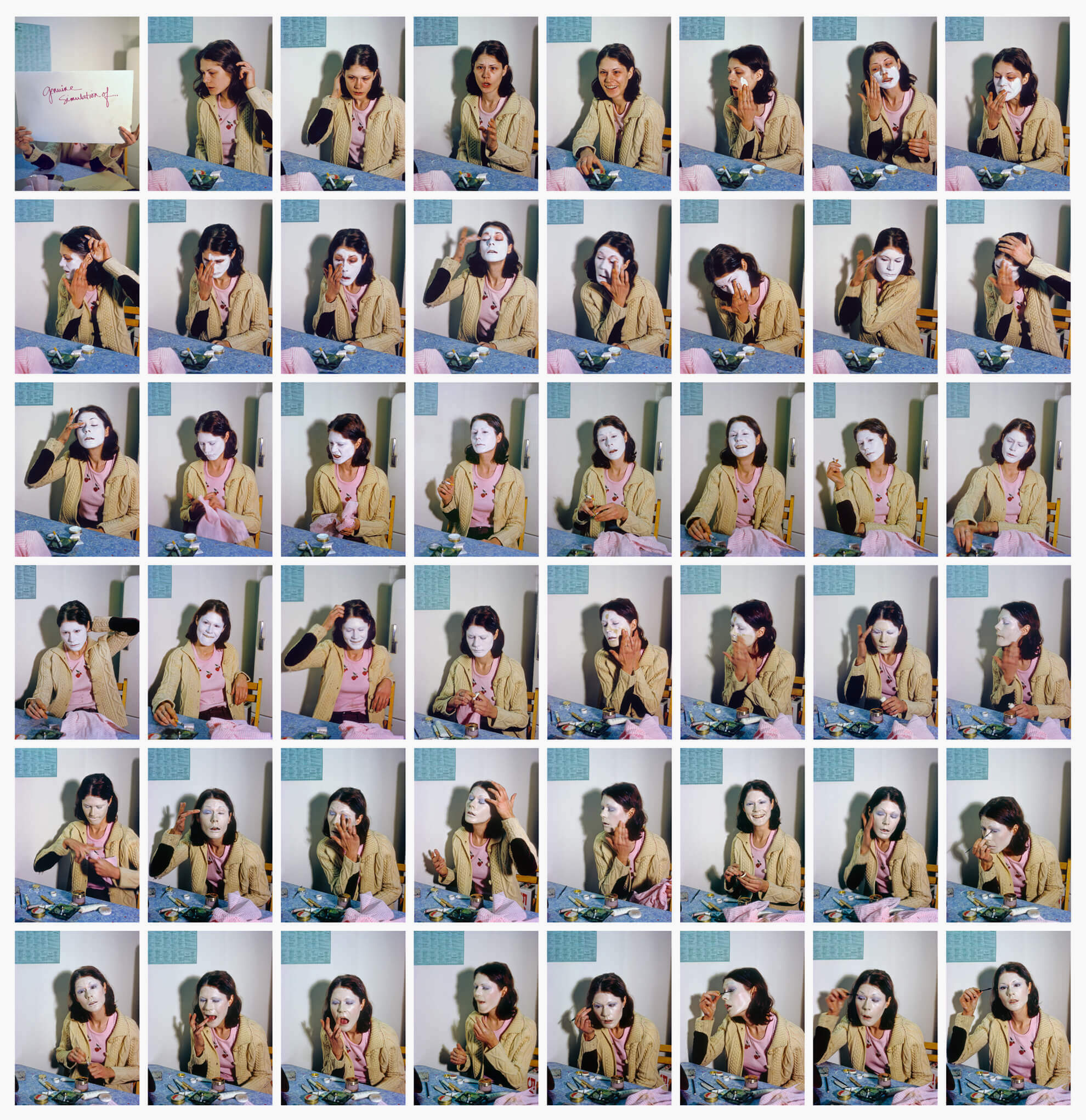

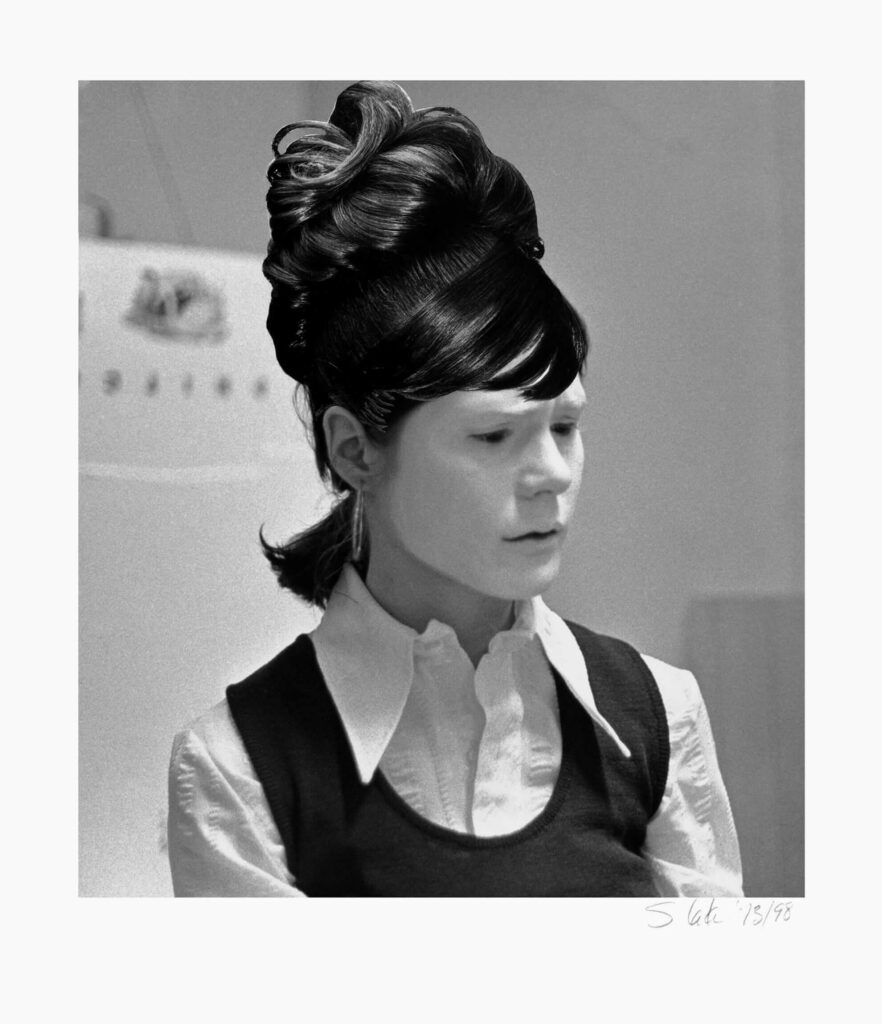

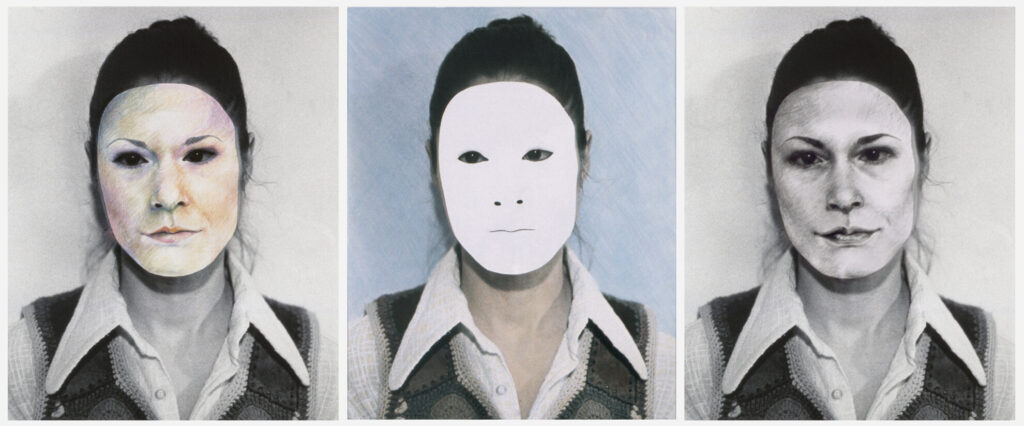

Works like On Stage, 1972–74, show Lake merging photography (as documenting a process) and the body (as a site through which to enact the process). In this series she initially posed for photographs in a manner that mimicked fashion photography; twice, later, she returned to the photographs—in 1973 adding new text and in 1974 adding an entirely new set of self-portraits. These photographic additions feature Lake in whiteface makeup—signifying a “zero” state, without individual character—effectively fusing painting, performance, and photography, a central strategy to which she returned throughout the early 1970s, as in Imitations of Myself #1, 1973/2012, and A Genuine Simulation Of …, 1973/1974. Imitations of Myself #1, composed of forty-eight chromogenic prints arranged in a grid of eight by six, documents an entire cycle of transformation, showing Lake seated at a table, initially without makeup, and gradually going on to cover her entire face with the white makeup. In most of the images, Lake appears dabbing the makeup onto her face with her fingers; in a few, she appears to pause and engage in conversation with someone out of the frame. By the final row, with her face entirely covered, she continues her transformation by applying lipstick and mascara to her visage—by now, transformed into a zero-state palette.

Lake’s series reveal the method she uses to select works to exhibit, pulling from a vast photographic repertoire in which the documented performances themselves were often unpredictable. In this way she ultimately exerts control. She often returns to previous works to explore new issues related to the original concept, imbuing the work with different formal or political concerns and/or considering the concept from a new vantage point. In Rhythm of a True Space #1, 2008, for instance, during a major renovation of the Art Gallery of Ontario, she revisits Re-Reading Recovery, 1994–99, with the images transferred to a vinyl wrap on the construction scaffolds that surround the building. For this project Lake took the photographs from her 1994 performance and enlarged them to a massive scale, and then, through their presentation as one consecutive image, introduced an element of rhythm previously latent in the original work.

In all her camera art, as the process develops, Lake is open to new ideas—even years later. “My favourite works are those from which I learn more than I could have ever expected,” she writes. “Regardless of Maquette or sketches, I do not follow plans as if to fill a prescription … The production process is invaluable in orchestrating a more complex narrative.”2

Performance

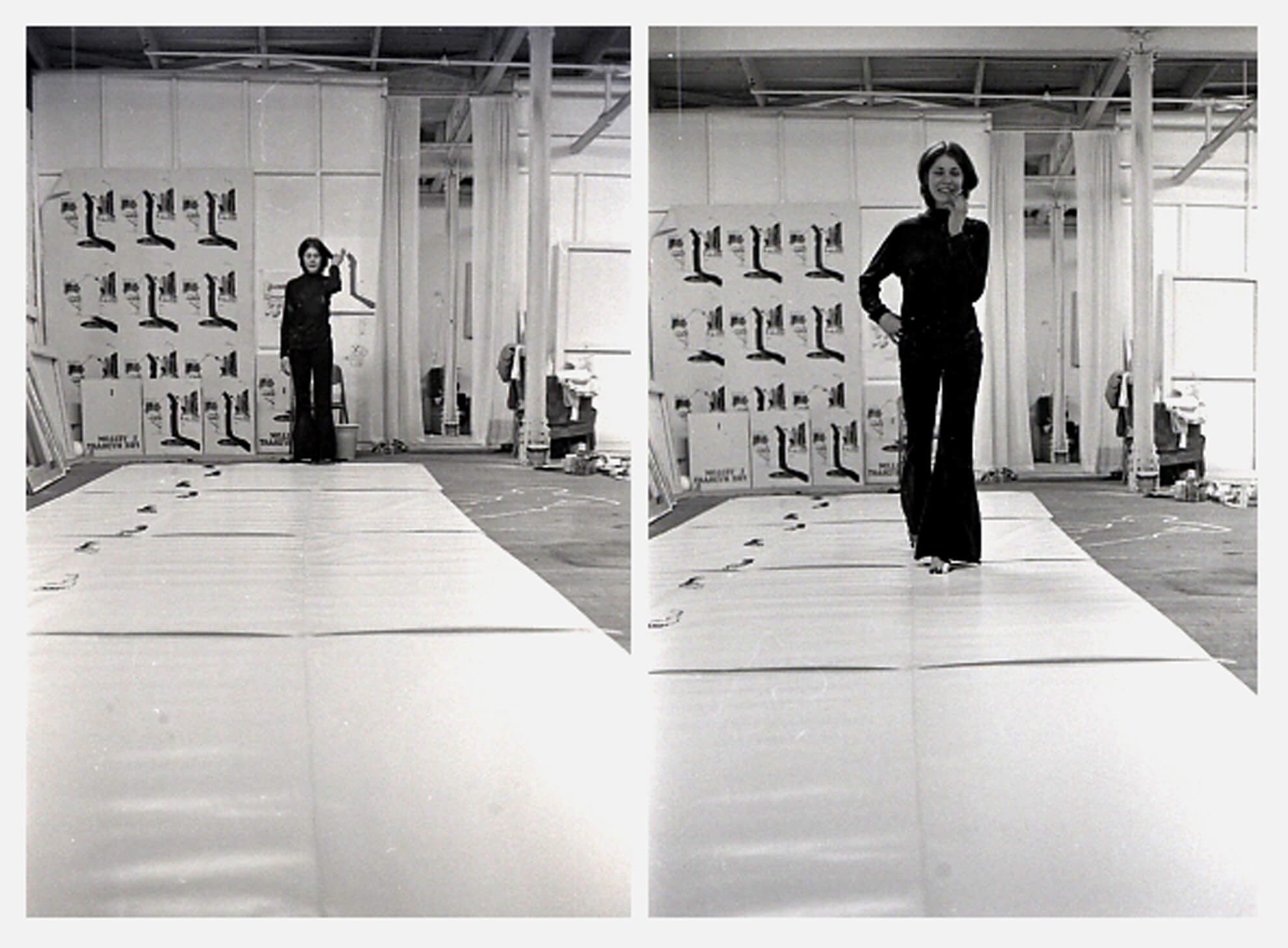

Lake’s work in the early 1970s also echoed the “Happenings” from that time—pop culture and political events where people gathered to experience a performance together or make their protest. During Lake’s studio performance/event Behavioural Prints, 1972, friends dipped their feet in paint and walked across a long sheet of paper, then allowed the paint to dry, switched positions, and followed the line again. This work perhaps recalled Automobile Tire Print, 1953, by Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008)—a collaborative effort with composer John Cage during which Cage drove his Model A Ford in a straight line over sheets of paper he had glued together. Behavioural Prints also echoed Anthropometries, 1960, by Yves Klein (1928–1962), for which the artist used models—“living brushes”—covered in blue paint to produce his canvases. In these events that transpired in Lake’s studio, the invisible participant is Lake’s studio, which, over the course of her career, has functioned as more than a place to make work behind the scenes; it is an active space whereby social and political events occurring outside can be explored through artistic means. As Lake has reflected, “I do believe that a lot of the elements that influence or provoke my work happen in the world. I’m able to bring all those influences, the raw materials, into the studio and put them on the walls, have them on the floor, test them off among other things and form the work.”3

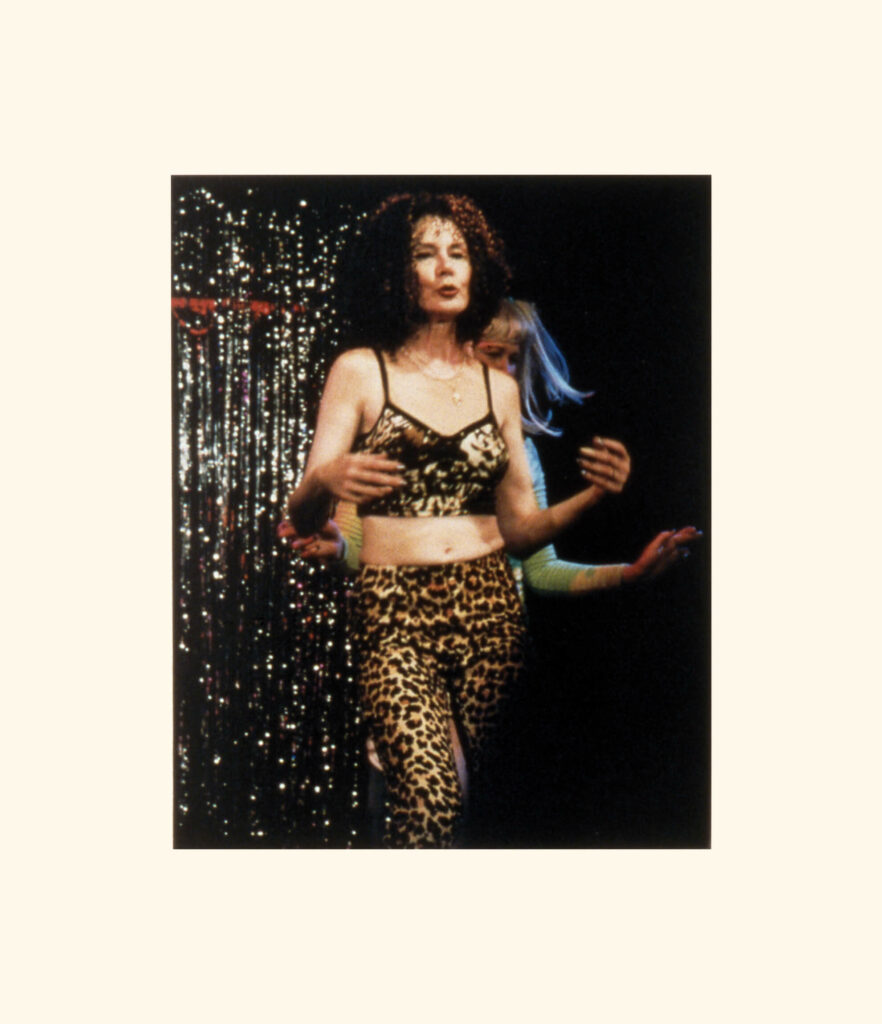

Lake’s photographs capture carefully constructed performances staged for the camera and for audiences—as in Forever Young, 2000, her series of three chromogenic prints showing her playing guitar, dancing, and singing as she holds a microphone. Through her photographs, Lake records her exploration of conceptual questions that she acts out using her body—in Forever Young, her probings about the aging female body. Photography is “evidence” or “a record,” as she described her performance for the camera in A Genuine Simulation Of …, 1973/1974, in which Lake, dressed in a plaid shirt and seated at a table with a matching tablecloth, her face bare, proceeds to apply layers of whiteface, blush, and mascara, pausing to light a cigarette or examine her work in the mirror. In the last frame of the ninety photographs she selected is Lake’s reflection in the mirror. All through the series, which is presented in a grid arrangement, she interrogated how identity is formed and perceived—by herself, by others, and by society in general.4

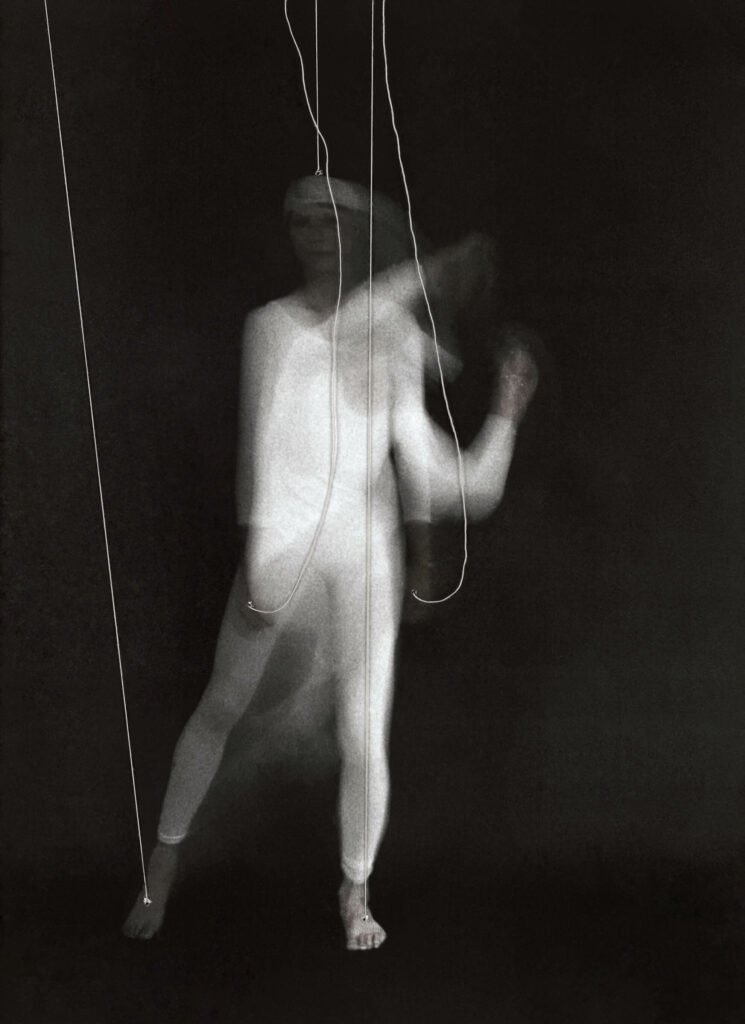

For Lake, photography creates images of performance and of movement, and it can capture something the eye does not see. In Choreographed Puppets, 1976–77, for example, she, as the performer controlled by the puppeteers, became unrecognizable because of the blurring caused by her manipulated movements—as had happened during experiments with chronophotography in the 1800s, in which early photo practitioners attempted to capture figures in motion. On Stage, 1972–74, in contrast, appears to stop motion.

Lake’s photographs are documents of various performances, all of which have been orchestrated in such a way that the camera is not merely a recording device but an active player in the staging, performance, and outcome of the work. In Are You Talking to Me?, 1978–79, Lake repeats the famous question Robert De Niro asked in the film Taxi Driver, only this time directing the question to herself, and using the camera to capture the subtle shifts in facial expression and the position of her lips and head. Presented in a sequence that appears to be rhythmically installed, the mouth aligns in all the pieces as though mimicking a film strip or an animation reel. This work is a re-staging not only of a performance but of an experience of breaking down the cinematic fourth wall: Lake engages members of the audience directly and invites them to replay the same feeling of anxiety and angst that she felt as she wrestled with this question.

Lake’s performances are inextricable from the act of taking the photograph, and the body—Lake’s body—becomes a medium in and of itself, open to the very types of manipulations and distortions that Lake performs and experiments with in her photographs. These aspects mirror Lake’s concerns with process, duration, and endurance. In Box Concert, 1973–74, an early video piece, for example, Lake holds a long box (a container for a roll of backdrop paper) and lifts it over a table again and again. Her attempt to repeat the original movement sets the narrative of the piece in motion and also employs the body—Lake’s body—as the necessary force to permit the action to continue.

Lake has acknowledged the influence of 1960s experimental dance by artists including Yvonne Rainer (b.1934) and Simone Forti (b.1935), as well as Anna Halprin (b.1920), Deborah Hay (b.1941), and Meredith Monk (b.1942), saying that she “learned something from each one.”5 In addition to Lake’s training in mime, she identifies Rainer’s use of daily life as a narrative and Forti’s animalistic movements that cross-pollinate between dance and mime as being particularly influential.6 Lake has also noted that, while studying mime, she often took dance classes, and it was likely there that she first learned about the Judson Dance Theater.

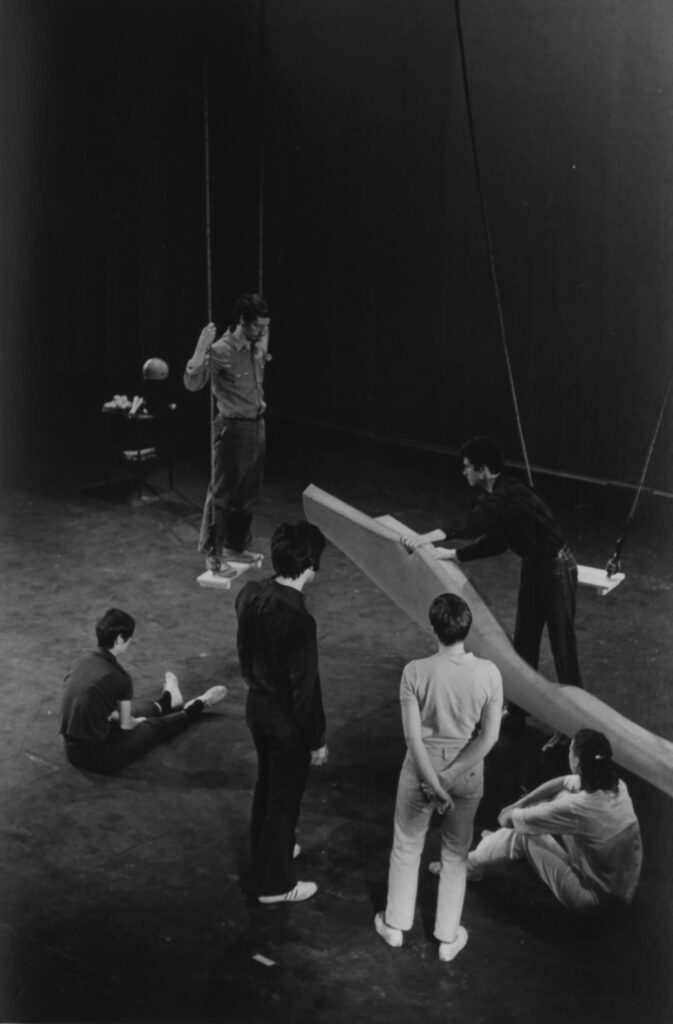

As its title suggests, Choreographed Puppets involves dance and the choreographies of the body.7 Although it is regularly described as “performance-photos,” it evokes Rainer’s multipart performance The Mind Is a Muscle, 1968, which is often referred to as a “dance-theatre situation” and “image-making in live form.”8 Choreographed Puppets is complex and multilayered. In it, Lake not only explores loss of identity in the face of control by others, but also retains a physical control as the director of the scene. She establishes the construction as well as the script for the unpredictable performance that occurs; she remains the author despite the work’s attempt to subvert authority.

Lake shares this control with Forti, whose Five Dance Constructions and Some Other Things, 1961, sprung from a set of scripted directions that functioned as the groundwork for a series of seemingly unpredictable movements that she expected to emerge from the dancer’s body in relation to force and gravity. Dancers improvised movements as a mode of negotiating the objects included in the performance, such as ropes and plywood boxes. Rainer and other dancers also performed works where their bodies encountered other bodies and inanimate objects in loosely scripted yet unpredictable ways. All the works now exist only in photographic documentation.

While Lake was influenced by these experiments with the body, for her the camera became an invisible yet ever-present witness. A re-enactment of Choreographed Puppets by Toronto-based choreographer and dancer Amelia Ehrhardt during the exhibition Introducing Suzy Lake at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2014 illustrated how dance could be translated back from photographic documentation. In the course of the performance, spectators were straining, simultaneously, to take in both Ehrhardt’s intense re-performance and Lake’s original photographic sequence. In this way, Lake’s work continues to bridge the gap between performance and image in new ways that defy convention.

Manipulating Photography and Film

Although Lake abandoned painting in the early 1970s as she became invested in photographic processes and modes for documenting performance, she transferred the tactile qualities of painting to her work in photography—notably by using camera film and other photographic techniques as tools for studying and testing the limits of time and representation. She not only embraces but also stretches photographic technologies to explore different modes of perception.

Through her tactile manipulation of the photographic surface, both pre- and post-exposure of film, Lake evokes the innovations of early photographic practitioners and avant-garde artists testing the perceptual possibilities afforded by photography, for instance, the composite photography of Oscar Rejlander (1813–75), the late-nineteenth-century experiments in chronophotography by Étienne-Jules Marey (1830–1904), and the perfection of the technique known as solarization by Man Ray and Lee Miller in 1929.

Early in her career, Lake began to manipulate photographs. She drew or painted directly onto photographic prints, referring both to her own training as a painter and the hand-tinted photographs from the late nineteenth century. In A Genuine Simulation of … No. 2, 1974, Lake explores the painterly qualities of makeup. In just six black and white headshots, she applied cosmetic makeup directly to the photographs themselves. In this way she evoked early photographic hand-tinting and her own training in painting even as she explored the tactility and malleability of the photographic medium. She also produced composite images, such as Suzy Lake as Gary William Smith, 1973–74, in the Transformations series, by using stencils in the darkroom to print selected areas of a picture. Lake also experimented with manipulating film itself: to make ImPositions #1, 1977, Lake heated her negatives and stretched them to produce a distortion effect.

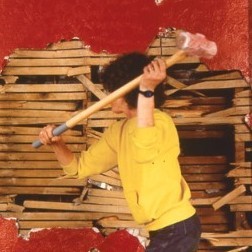

In addition to the physical manipulation of her film, Lake has also experimented with strategies of perceptual manipulation, engaging the space between the content of the image and its borders to confuse the limits of the photographic frame. In Pre-Resolution: Using the Ordinances at Hand, 1983–85, and My Friend Told Me I Carried Too Many Stones, 1994–95, she showed her fascination with illusion and with the boundaries of the photograph and its frame. In both works, she used her body to produce a trompe l’oeil effect similar to those adopted by Canadian artist Michael Snow—for example, In Media Res, 1998, where three people chase a bird over a panoramic photograph glued like a rug to the gallery floor. In these two works by Lake, the viewer is able to perceptually look “beyond” the surface of the photograph, into the recessed space Lake appears to be excavating, for instance, by demolishing the red wall depicted in Pre-Resolution: Using the Ordinances at Hand, or by scratching at bits of torn wallpaper on the surface of the wall in a photograph overlaid on a photograph of the same wall in My Friend Told Me I Carried Too Many Stones.

In recent years Lake has continued to challenge the limits of photography, often experimenting with duration and exposure time to create powerful visual effects. In Reduced Performing, 2008–11, Lake “photographed” herself on an eight-foot flatbed scanner engaging in various subtle and expressive gestures such as blinking, breathing, or crying as the scanner captured her over the course of twelve minutes. The result of direct engagement with the digital scanning technology—different from photographic capture—was that instances in which Lake moved slightly, such as in breathing, resulted in digital drag (blurring and smudging of the image) on Lake’s clothing, while movement resulting in contrast, as with Lake’s eyes, resulted in RGB colour breakup—an effect where the colours appear to break apart and breach the authenticity of the image.

Lake again used her body to explore the long-time photographic questions around movement, light, and exposure in Extended Breathing, 2008–14. In this series she stood still for an hour-long exposure as the camera captured her surroundings with perfect clarity. Lake herself appears slightly blurred because of her physical need to breathe. Once again, the body—the constant—allows invisible perceptual phenomena to become visible.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements