Alex Colville’s paintings are distinctive and easily recognizable, marked by his careful, unified brushwork and meticulously arranged compositional structures. Another key process for the artist was printmaking, which appealed to Colville in its inherent limits and capacity to create multiples. He worked as a figurative painter throughout his career, focusing on an ideas-based approach. Although always a representational artist, he was interested in presenting images that expressed thoughts about the world, rather than mirroring it.

Finding His Voice

Alex Colville studied at Mount Allison University in Sackville, New Brunswick, and was influenced by his teacher Stanley Royle (1888–1961), an established Post-Impressionist painter from the U.K. Additionally, Colville had an enduring love of early Renaissance painting. Brief exposure to historical European painting, in particular the works of Giotto (c. 1267–1337) and Paolo Uccello (1397–1475) at the Louvre in Paris during the Second World War, provided Colville with years of inspiration. “I realized, that it might take me years, for instance, to absorb the effects of the two days I spent in the Louvre,” Colville wrote. His technique of laying down tiny, individual strokes of pure colour to build up a luminous, rich surface, despite its lack of texture or material depth, lent his brushwork an invisibility that echoed the early Renaissance painters’ flatly painted surfaces.

Colville was interested in such diverse artists as the American Luminists and Precisionists, and by such Realists as Thomas Eakins (1844–1916), Edward Hopper (1882–1967), and Ben Shahn (1898–1969), artists who were interested in imbuing the daily activities of their surroundings with symbolic depth, a strategy Colville shared throughout his career.

In the early 1950s the British artist Henry Moore (1898–1986) was a marked influence, as is apparent in the sculptural forms in Colville’s series of nude figures in landscapes, such as Nudes on Shore, 1950. The poses, the treatment of detail, and the settings are all reminiscent of Moore’s sculpture and drawings from this period. Though Moore had achieved quite a lot of fame during the Second World War with his shelter drawings, 1940–41, it was the Saint John, New Brunswick, painter (and fellow war artist) Miller Brittain (1914–1968) who led Colville to study the works of the great British sculptor. In the early 1950s Colville started making work he considered mature: “When I finished Nude and Dummy I said, ‘Now I sense that I’m kind of on to something’—what people in literature and poetry speak of as a poet finding their voice.”

Ideas in Material

In the late 1940s Colville was primarily working in watercolours and oils, the materials that he had used as a war artist. Works such as Railroad over Marsh, 1947, even looked like his war art in subject, composition, and technique. By 1950, however, he had also begun to use tempera as he strove to find a medium more conducive to the hard edges, simple lines, and meticulous layering of marks with which he constructed images. He painted his 1948 mural, The History of Mount Allison, in egg tempera on canvas, which was then adhered to the wall. He also completed smaller paintings, such as Nudes on Shore, 1950, in egg tempera.

As the 1950s unfolded, he sought clarity in his materials and made a deliberate shift in his subject matter, focusing on the human figure, in order to communicate more effectively. As he explained in a lecture, “Now I realized that I couldn’t go on using horses as my only organic forms, and also that oil painting was entirely unsuited to my method of working. I therefore decided that I would paint the human figure and that I would use tempera.”

Colville described himself as a “conceptual” artist, no longer relying on what he saw around him, but instead constructing images out of elements both found and invented. As he wrote in 1951, “The conceptual artist operates more independently of mundane experience; perceiving or seeing for the conceptual artist is a process which is used to confirm or to modify what he has already determined.” Colville uses “conceptual” differently here than it has come to be used in art history and theory, denoting not the 1960s idea of an art movement dedicated to the “dematerialization of the art object,” but rather to a very material and philosophical position that painting is a form of thinking. As such, it is an accurate and appropriate use of the term as it relates to his practice.

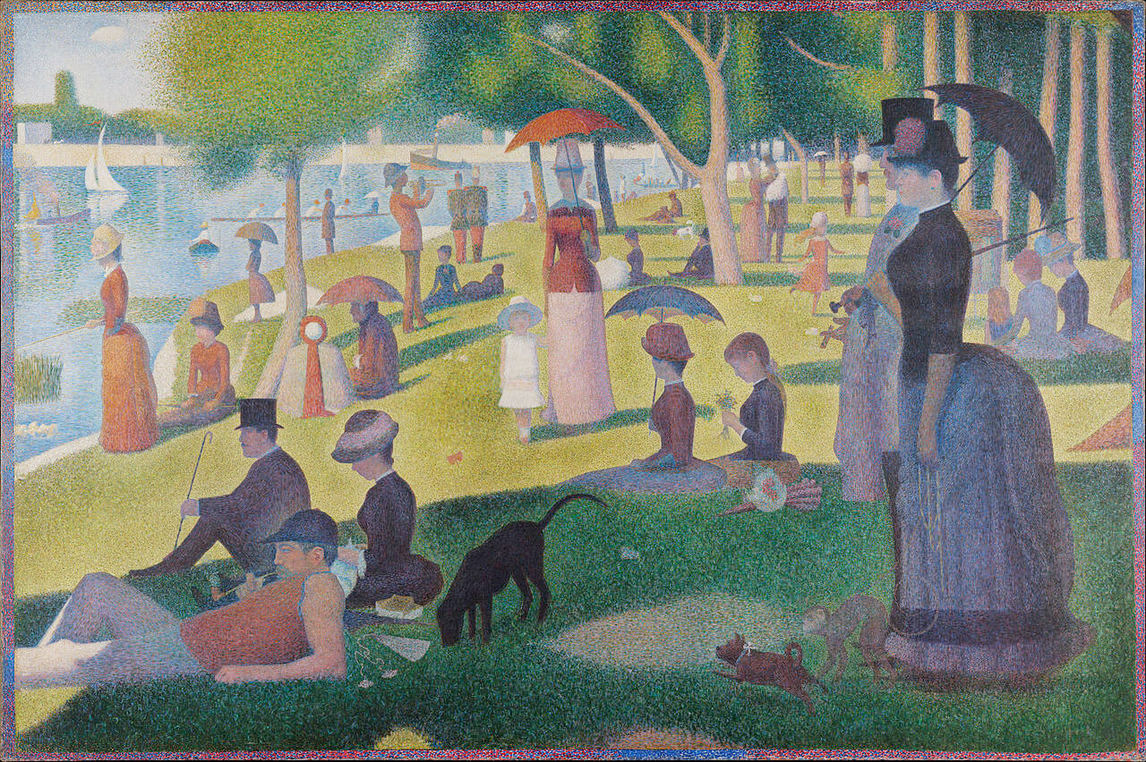

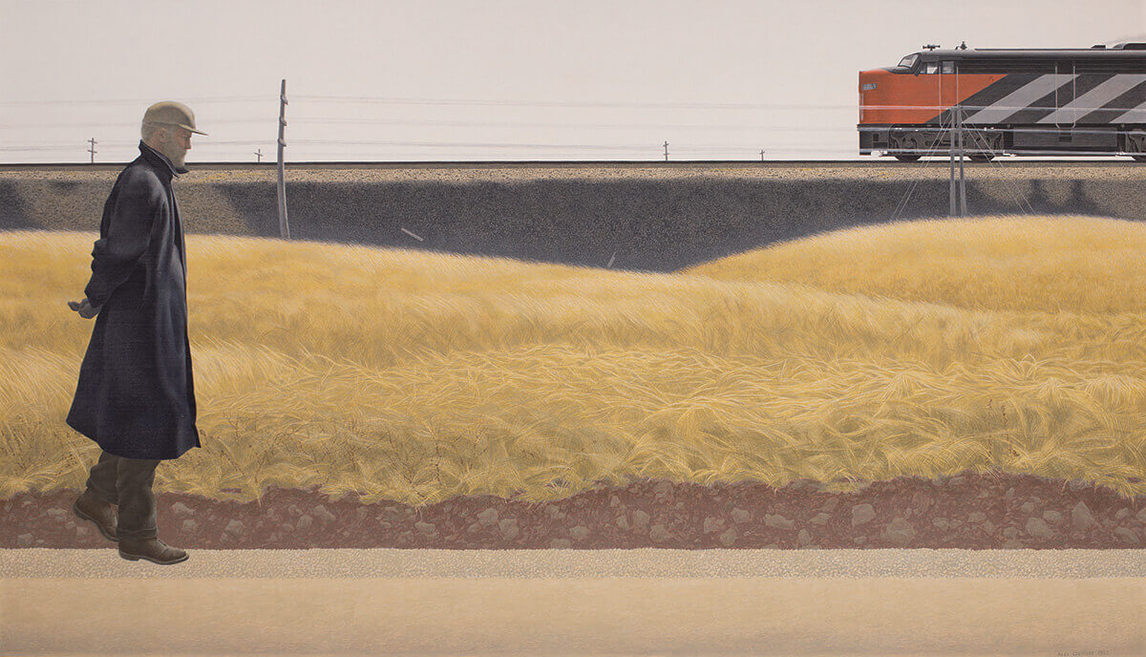

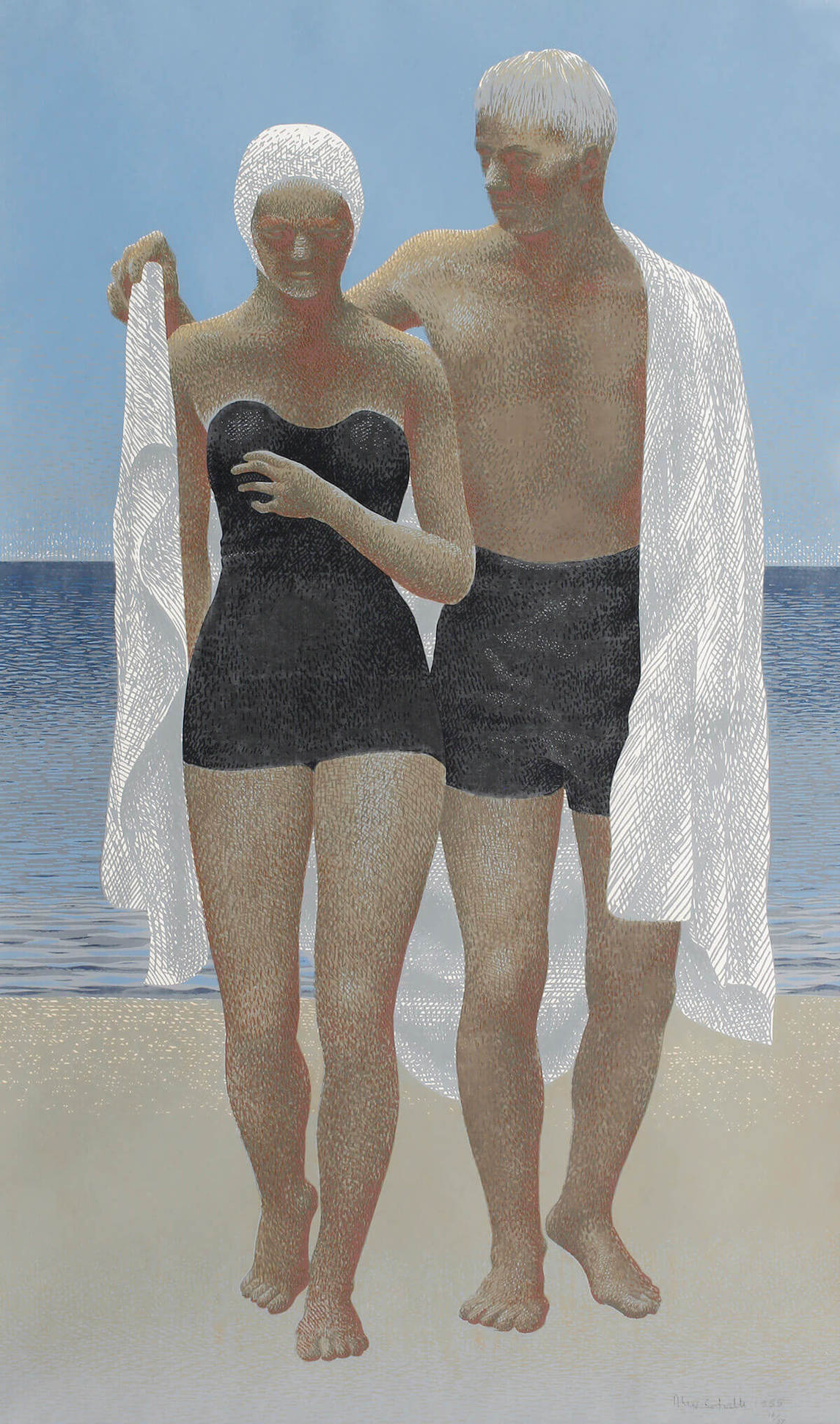

Colville’s mature painting style is based on a pointillist approach of layering marks next to each other, each mark a tiny point of colour. The sum of the parts makes the image and the tone, and the colours are not mixed in the strokes themselves. Though the technique was pioneered by Georges Seurat (1859–1891) and Paul Signac (1863–1935), Colville used a much less expressive style of pointillism that does not draw attention to the tiny strokes of colour that comprise his compositions. To that end, Colville worked with fine sable brushes, mixing each colour with a binder to create a unified surface. Glazing at the end of the process ensured a coherent, almost seamless surface. Additionally, the works are constructed on a complicated and rigorous geometric underpinning. That combination, first arrived at in the early 1950s in works such as Nude and Dummy, 1950, Nudes on Shore, 1950, Two Pacers, 1951, and Four Figures on Wharf, 1952, marked a change in style from which Colville never deviated. Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s Colville switched between tempera (casein or egg tempera) and oil. By the mid-1960s acrylic paints had achieved a quality and consistency such that Colville soon began using them exclusively, and did so until his death.

Studies: Sketches, Photographs, Watercolours

Alex Colville always drew, both as a compositional tool and as an aide-mémoire: making sketches of scenes or ideas that might have a reference in a painting he was currently contemplating. For Colville, painting was a way of thinking, and sketches played an important role in ordering thoughts: “The exploration of the unconscious, which is what I think I am doing, essentially, can only be undertaken with some kind of butterfly net, some kind of aid—something that can catch things.”

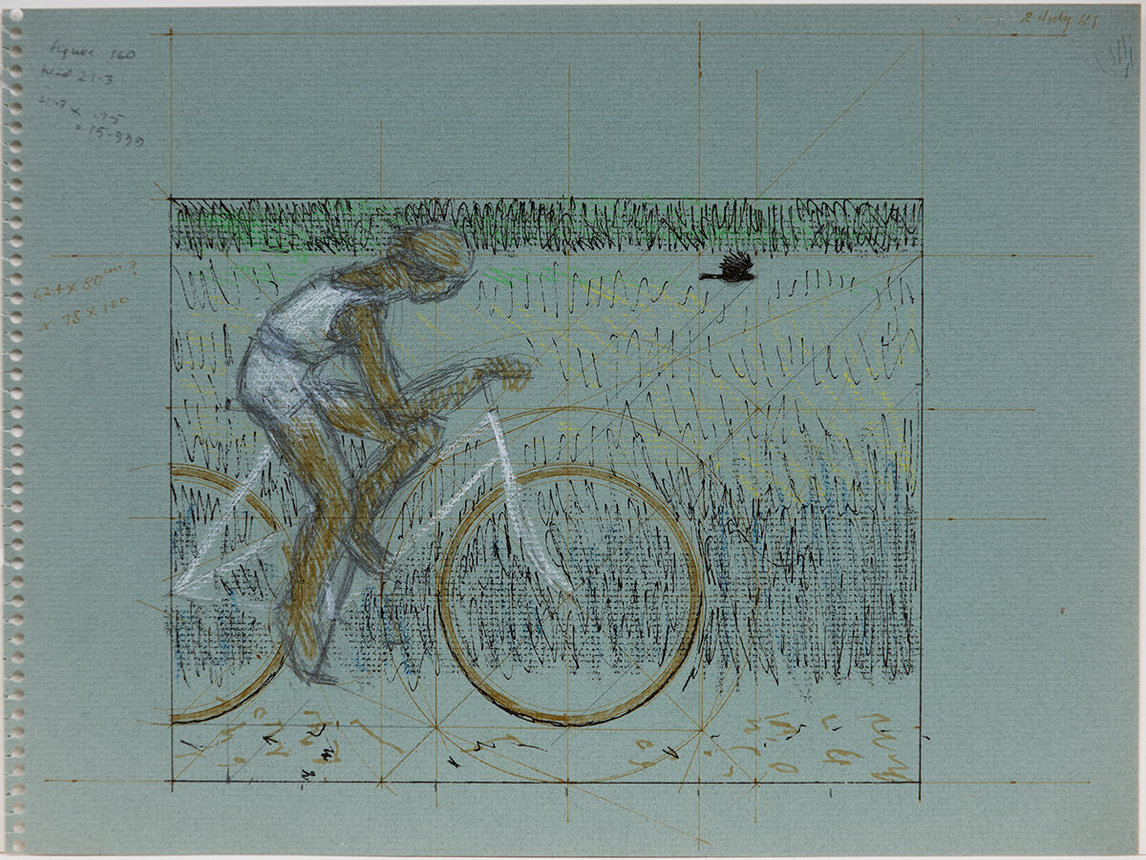

He used a camera as a tool for composition, collecting images he might use only months or years later. Colville employed photographs for depicting specific elements, such as the female on horseback in French Cross, 1988, which he combined with another element (in this case the Acadian Deportation Cross at Grand Pré, Nova Scotia) in order to make a complete composition. Colville distinguished the difference between a photograph and a painting, noting that a photograph is “taken” while a painting is “made.” Curator Philip Fry wrote of Colville’s relationship to photography that “in striking contrast to the photographic image, what happens in Cyclist and Crow appears as the embodiment of a mental image through the exercise of the painter’s competence as an artist, what could be called a ‘slow’ and ‘body-centred’ technology. The painted gesture is a construct of the imagination; it has not been taken or abstracted from time.” Fry’s point holds for any of Colville’s paintings—the camera was merely another tool. “As a good realist, I have to reinvent the world,” the artist said.

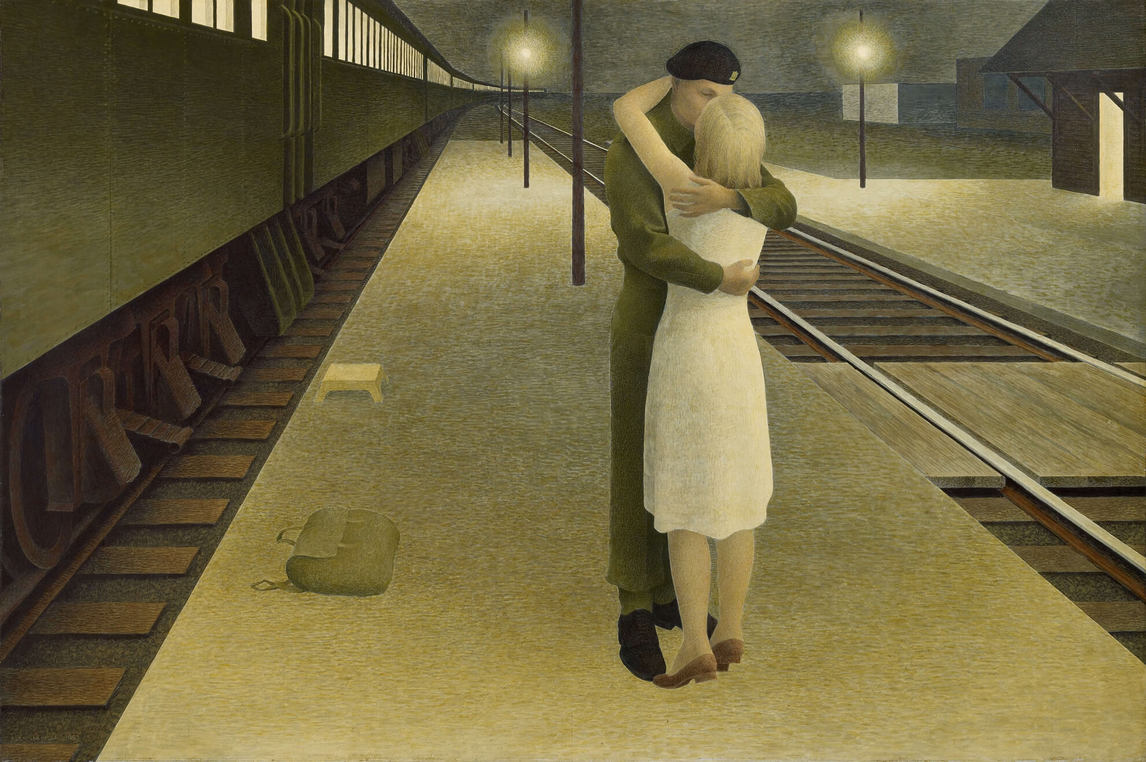

Another important tool for Colville was the medium of watercolour, which he mainly used to capture colour decisions in his sketches, for example, Study for Sackville Railway Station mural (Soldier and Girl), 1942. Though from his youth until the 1950s he turned to watercolours frequently, he stopped employing them in finished works after he discovered tempera and acrylic emulsions. A ruler and compass were as integral to his art supplies as a pencil or brush, and he filled sketches with mathematical notations and geometric calculations.

Geometry as Structure

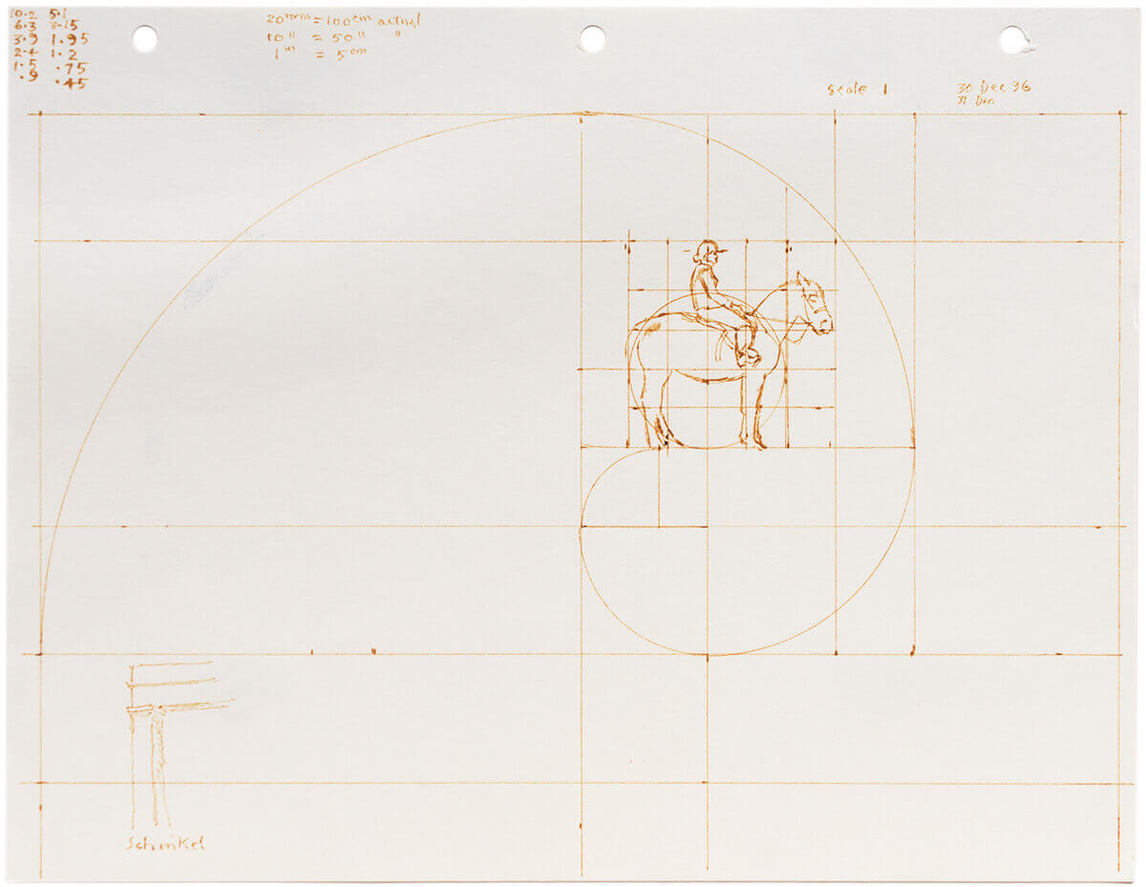

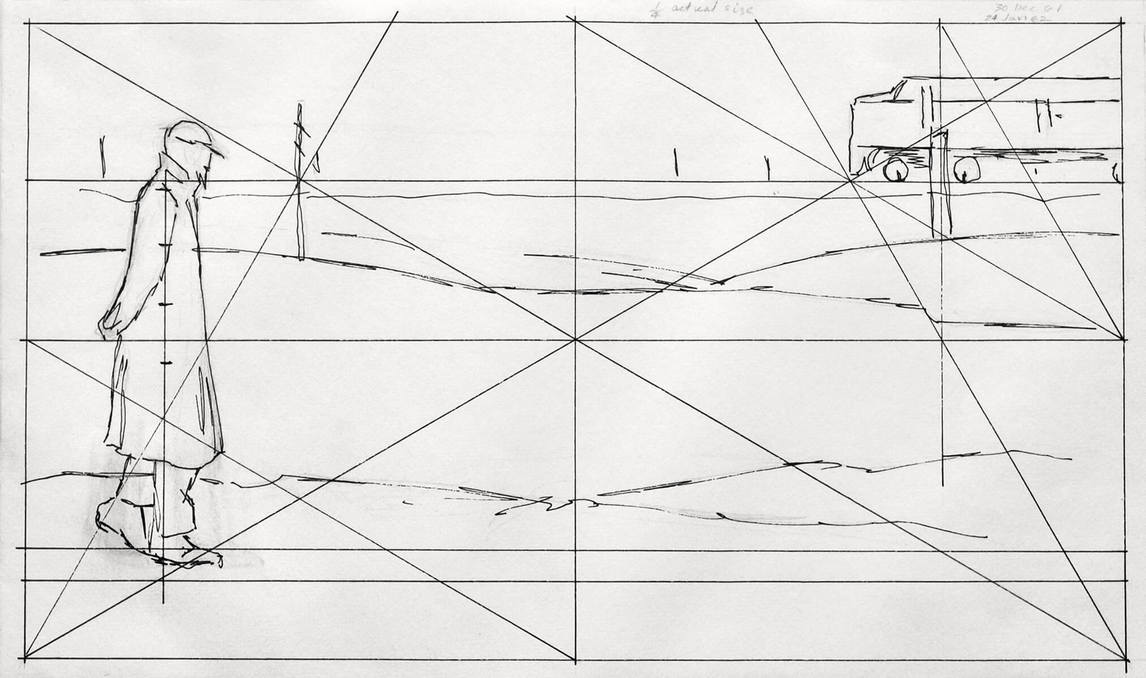

Colville’s passion for order begins with the underlying geometry of his image, a rigid skeleton of geometric relationships that dictate every aspect of his compositions. “Geometry seems to be a way into the process,” he said. “If I were a poet I would write sonnets. I would not do what you speak of as ‘free verse.’ I work within existing forms.” Often based on the golden section, his geometry is a construction technique. As curator Philip Fry noted, Colville used geometry as a “regulatory system”—as a way of imposing coherent, predictable, and orderly relationships between objects in his compositions. Often borrowed from architecture, these systems could be relatively simple, as in the golden section, or more complex, as in the Modulor system of Le Corbusier (1887–1965) and the ratios derived from the mathematical sequence called the Fibonacci series, for example, in Study for St. Croix Rider, December 30–31, 1996.

Colville’s meticulous sketches show how, before he began to paint, the image and the geometry evolved as he arrived at a composition that communicates the ideas and feelings he looked for. As art historian Martin Kemp writes: “The concept for the picture is triggered by his vision of a pregnant moment in the life of things. The picture shape that ‘fits’ the subject is then altered by repeated geometrical structuring using complex overlays from Colville’s repertoire of inscribed circles, squares, triangles, logarithmic spirals, and ratios. Human proportionality, which is based on a system of head lengths beloved of Renaissance architects and more recently Le Corbusier, has an important role in these paintings that involve his cast of wordless characters.”

For example, there are twenty-one studies for Colville’s painting Ocean Limited, 1962, in the collection of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. The sketches were primarily used to work out the geometric underpinnings of the major compositional elements: how the head of the walking figure and the train engine line up, the relative placement of the horizontal elements of the railway embankment and road, and the vertical elements of telephone poles and the walking figure in the foreground.

Order as mathematical correspondence is an ancient idea, stretching back to Pythagoras and earlier in our intellectual history. Nobel Prize–winning physicist Frank Wilczek sums up the persistent belief that a beautiful order underlies the apparent chaos of the world in a discussion of the Pythagorean aphorism, “All things are number”: “For the true essence of Pythagoras’s credo is not a literal assertion that the world must embody whole numbers, but the optimistic conviction that the world should embody beautiful concepts.”

In organizing the composition by use of “beautiful concepts” to establish an orderly underlying framework, Colville adds a sense of solidity to what at first appears as a scene taken from observation. Geometry determines the perspective, ensuring that the image, however much an invention, feels right to the eye. An almost subliminal sense of proportion and alignment conveys the underlying geometric order. Ultimately, Colville’s geometry is most important not for its specific angles, arcs, or correspondences, but for the foundational rigour that the balanced geometric framework gives to the image itself. Seeking order, one must banish chance.

Structure and Routine

Colville was a creature of habit, with a routine that permeated every aspect of his artmaking. His working life was as structured as his paintings. Critic Jeffrey Meyers notes, “His schedule is as regular as Immanuel Kant’s in Königsburg. He rises early, walks the dog and works from eight to twelve. After lunch and a nap, he picks up his mail at the local post office and does some shopping, answers letters and makes phone calls, and lets the afternoon ‘kind of drift away’. After dinner at six he reads or watches television, is in bed at nine and asleep soon after.” Alex Colville thought long and hard about every aspect of his finished works, including the frames and the materials upon which he painted. Because he used egg tempera, casein tempera, and acrylic polymer emulsion—all of which dry hard and brittle—Colville worked on Masonite surfaces or other types of wooden panel. He did not want any flex or give, neither while he was working nor once the paintings were finished.

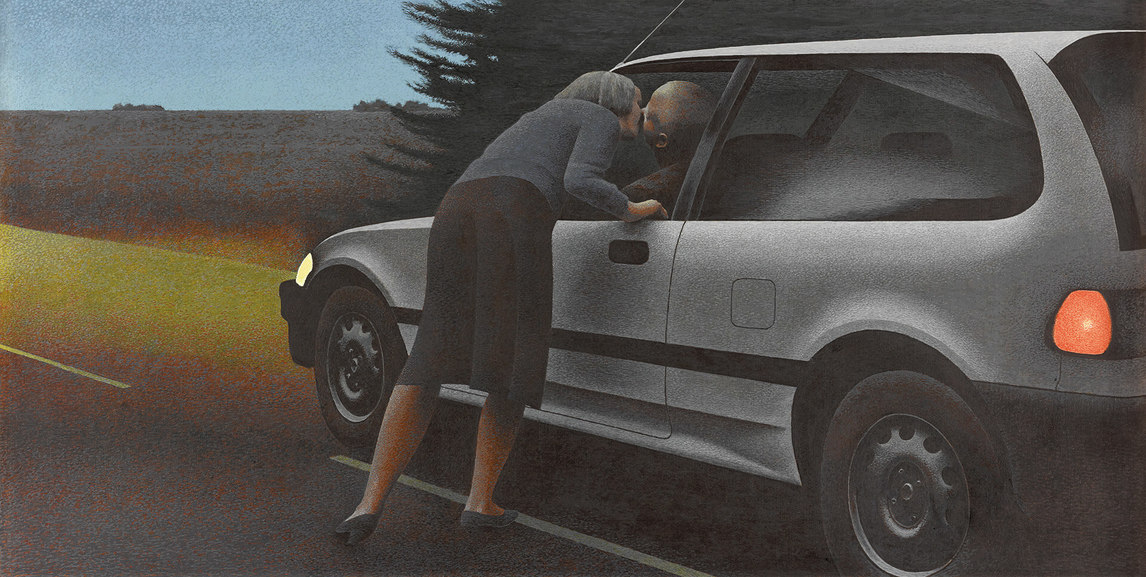

He also cared about how his works were seen, and he built and designed his own frames. Each simple and elegant wooden frame constructed by the artist from the late 1950s onward is unique, and reflects the artist’s passion for order. And yet it is rare to find images of Colville’s paintings that include the frames. Most major monographs on the artist omit them altogether. A welcome exception is Philip Fry’s book Alex Colville: Paintings, Prints and Processes, 1983–1994, in which all of the paintings are shown in frames designed and constructed by Colville. One can see his varied approaches: almost architectural and stark, painted black, in the case of Kiss with Honda, 1989, or Bat, 1989; less assertive and lighter in tone, painted in washy greys in the frames for Boat and Bather, 1984, or Western Star, 1985. This attention to detail is entirely consistent with Colville’s approach to artmaking, where being meticulous is as necessary as being thoughtful. Craft, the actual making of things, was important to Colville. As he said, “Anyone working in the visual arts is a kind of artisan.”

A Cinematic Painter

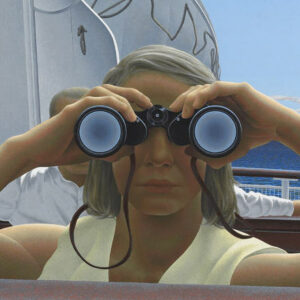

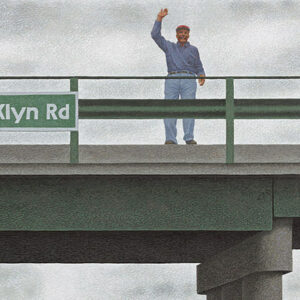

Film, arguably the most influential art form of the twentieth century, had a distinct impact on how Colville composed his images. He layered multiple viewpoints and time frames in his images, so that at first view the scene makes sense, but as one studies it further, it becomes apparent that different moments are pictured simultaneously, as in Horse and Train, 1954. Tom Smart writes, “The horse exists on an entirely different perceptual plane to the train; it is as if the animal has been collaged on the ground occupied by the track and train.” Colville’s use of slightly differing viewpoints, as if images registered seconds or moments apart, occurs in West Brooklyn Road, 1996. Here, the viewpoint is from a speeding automobile, but with a different focus in different sections of the painting—the oncoming truck is registered a few seconds before it, or the speeding car, reaches the overpass, creating a change in scale that reflects a time lapse in the point of attention. Much like in an early Renaissance painting, Colville depicts different times in the same composition. However, the shortness of the duration of the two time frames here points more to the influence of film on the artist.

Film was also ubiquitous; even tiny Sackville, where Colville lived for many years, had a cinema where popular films were on view in the manner conceived by their originators. This was not so for most fine art, for which Colville had to travel—something he did rarely. Film’s immediacy and its ability to tell stories and the way distinct images cohered together had an impact on Colville’s thinking about how he constructed his own images. Of film, and in the context of discussing Horse and Train, 1954, he said that he aspired to “the kind of immediacy that films have [and] this means what I think of as authenticating the thing so that it is not just a kind of an abstract or symbolic train, but a very specific, actual thing.”

However, Colville stated that he deliberately chose to live in Sackville to escape influence—he was not seeking to emulate anyone, but rather was intent on his own visual language and approach to painting. Colville never worked in a group and despite his inclusion over the decades in several “realist” exhibitions he never wholeheartedly adopted any school of painting as his own. Colville’s search for meaning was a conversation with history, with the past and the future, played out in the eternal present of each viewing of his work. He aspired to be wholly of his time, but also timeless.

Serigraphs

From 1955, in addition to his paintings, Colville worked with serigraphy. Usually in print runs of between twenty and seventy, Colville’s serigraphs, or silkscreen prints, should be considered of equal weight to his paintings, and they show little difference from his panels in subject matter and composition. Colville made thirty-five screen prints between 1955 and 2002, and in 2013 he donated an entire set to Mount Allison University, where he first studied and later taught. The donation comprises the only complete set of his screen prints in any public or private collection.

Serigraphs are made by pushing ink through a fine mesh onto a substrate, with the areas that are not to be that particular colour blocked by a stencil or other medium. A different screen is used for each colour. Colville made all his prints himself and never reproduced his paintings in this medium. Rather, each print is a unique composition. After Swimming, 1955, was Colville’s first published serigraph. This image reflects a theme that Colville returned to often throughout his career—the relationship between a man and a woman, specifically between husband and wife, as evidenced by the use of himself and his wife, Rhoda, as the models.

Though a complicated and demanding process, serigraphy took much less time than his paintings and allowed Colville to work in multiples. The relative immediacy of the technique (colours are applied over the whole surface and images appear at once rather than being gradually built up with thousands of brush strokes), the unforgiving nature of making images with colour applied through screens, and the inherent limits of the process, drew Colville’s interest: “One of the appeals of print-making is the discipline of the printing technique; in painting almost anything is possible—in print-making there are limitations of means; the concept must be adapted to a more economical mode of expression.” Interestingly, he didn’t branch out into other kinds of printmaking, nor did he, after the 1940s, create watercolours or drawings as finished artworks. He focused unswervingly on paintings and screen prints.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements