Alex Colville’s career spanned his service as an official war artist during the Second World War to his death in 2013. From the early 1950s he had achieved a signature style, maintaining a set of images, subjects, and contextual concerns that remained remarkably consistent. His family (in particular his wife, Rhoda), the immediate environs of his homes in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, and animals (often his own family pets) were his most frequent subjects.

Formative Years

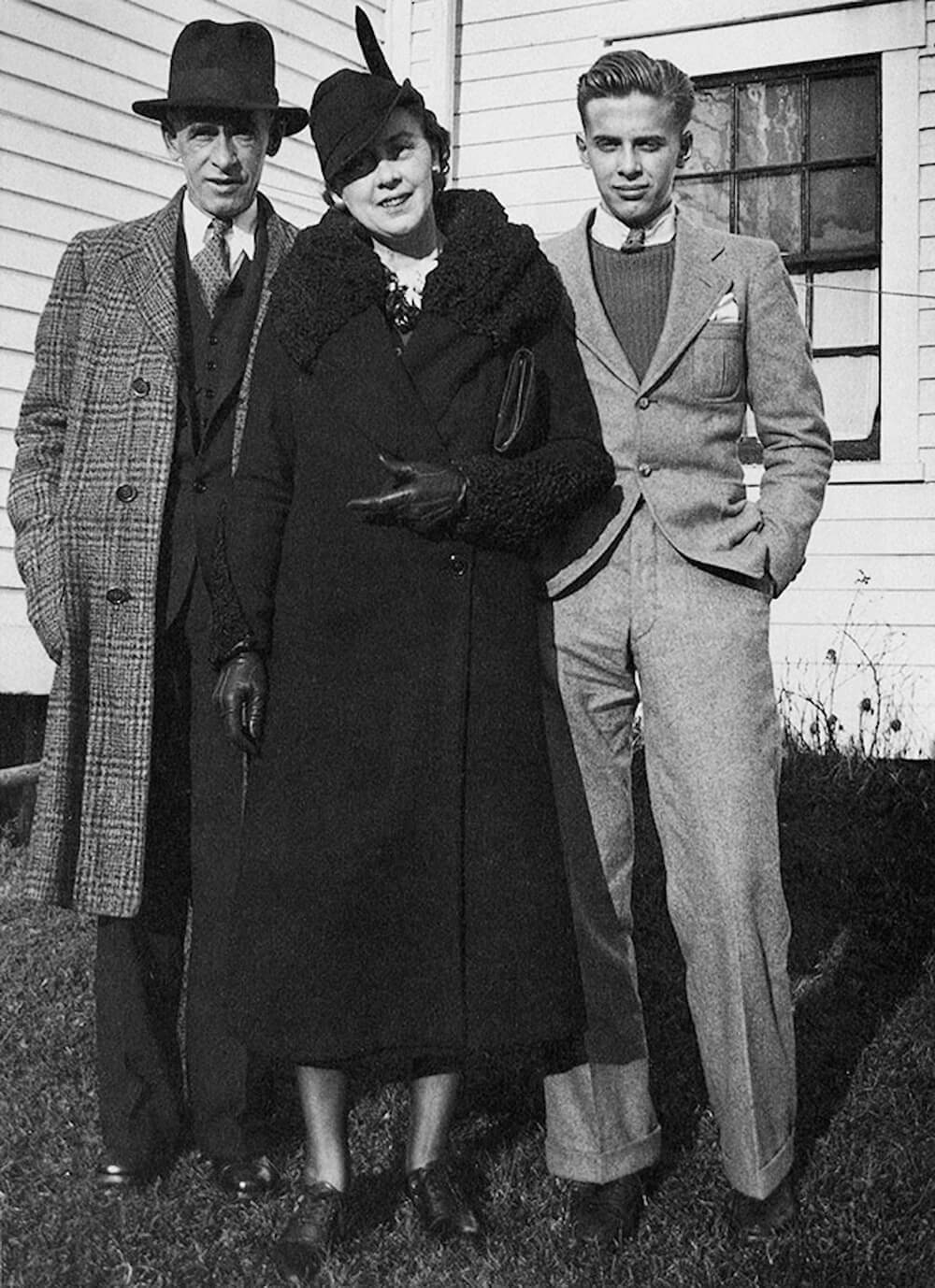

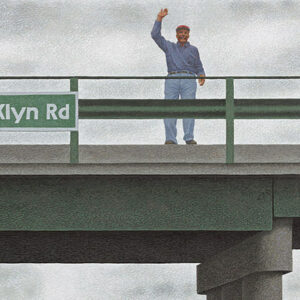

Although Alex Colville is often heralded as an iconic painter from the Maritimes, he was born in Toronto, on August 24, 1920. David Alexander (Alex) Colville was the second son of David Colville and Florence Gault. David Sr. was from a small Scottish mining town and immigrated to Canada in 1910. He spent his career working in construction, specifically in steel work, building bridges and other large engineering projects. In 1914 he married Florence, who was from Trenton, Ontario. David’s work kept them on the move for the first years of their marriage, with stops in Moncton, New Brunswick; Cape Breton, Nova Scotia; and Trenton. In 1920 they moved to Toronto, where their five-year-old son, Robert, soon had a little brother, Alex.

In 1927 the Colvilles moved to St. Catharines, Ontario, and two years later to Amherst, Nova Scotia. David had taken a job as plant supervisor at Robb Engineering and he worked there for the rest of his career. Florence apprenticed to a milliner and eventually started her own business. Almost upon arrival in Nova Scotia the young Alex Colville contracted pneumonia, from which, by his own account, he almost died. His recovery in those pre-antibiotics days was long and isolated, with six months of lonely bedrest. His mother supplied him with books and art materials, and he filled his time by reading and drawing, developing an interest in art that blossomed in the coming years. Colville notes:

I stress this business of having pneumonia and almost dying because I think it had an effect on me. In addition, I was lifted out of association with my friends and schoolmates. All through that spring and summer I led an almost solitary life. In this period I became what we usually call an introvert, one whose life is essentially a kind of inner life. I began to read, really for the first time, and I did quite a few drawings, simply because I was alone and had to find something to do. The drawings I made were all of machines, without exception. I drew cars, boats, airplanes, things like that.

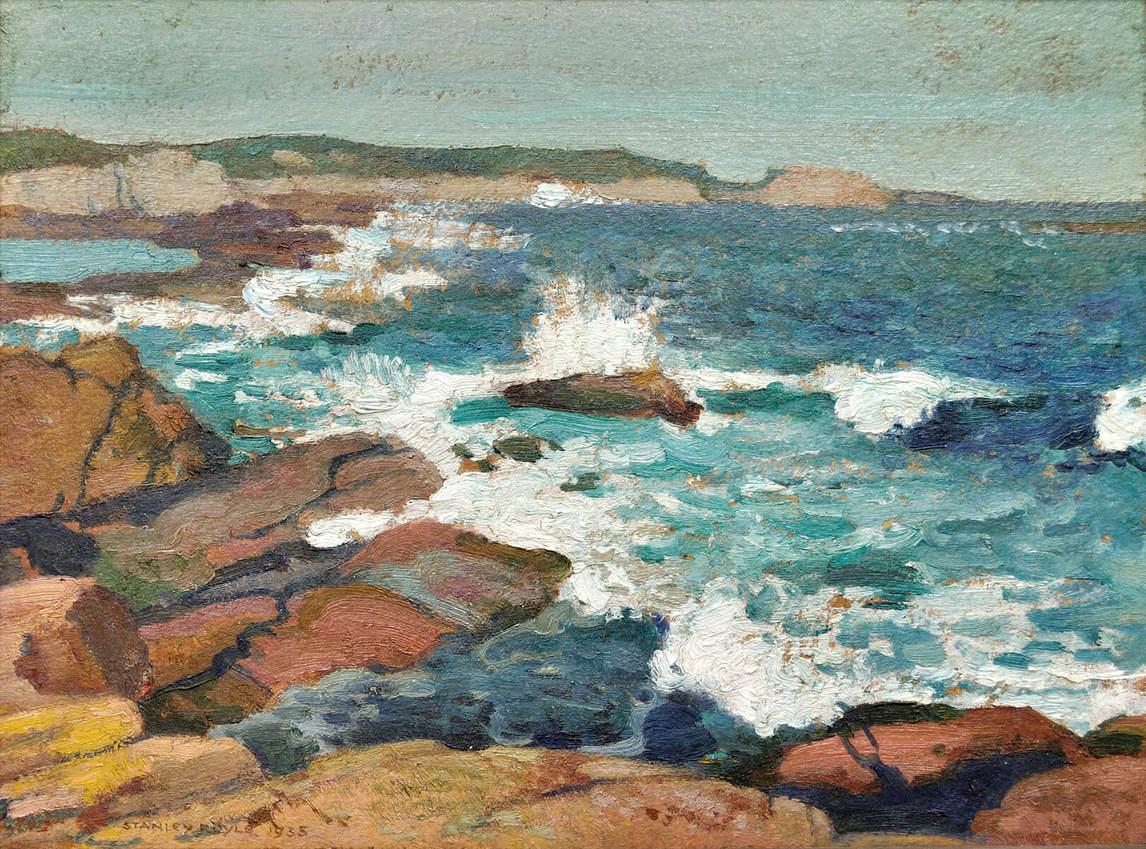

The interests kindled in Colville in those months of recovery found an outlet in 1934, when he began to take weekly art classes in Amherst. For three years Colville studied painting, drawing, and sculpture under Sarah Hart (1880–1981), a native of Saint John, New Brunswick, who had studied at The Cooper Union college in New York. Primarily a woodcarver, Hart also taught painting in a Post-Impressionist style influenced by her former teachers. Hart’s classes were part of an extension initiative, from New Brunswick, of Mount Allison University’s fine art department, which saw faculty holding classes in several small Maritime communities. Program faculty closely monitored participants in order to identify potential full-time students, and Stanley Royle (1888–1961), who became an important early mentor to Colville, took notice of the young student. “Once, or perhaps twice in each year, Mrs. Hart would invite the professor of fine art at Mount Allison University, Stanley Royle, to come and observe the work of the classes,” Colville remembered. “Mr. Royle gave me a lot of encouragement, he said that my stuff was good and that I should keep at it.”

Royle, from Sheffield, England, had joined the Mount Allison faculty in 1935 and taught there for ten years before returning to the U.K. in 1945. Royle was an accomplished Post-Impressionist painter working en plein air in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. He was a graduate of the Sheffield School of Art (now Sheffield Institute of Arts), as were his contemporaries Elizabeth Styring Nutt (1870–1946), the principal of the Nova Scotia College of Art (now NSCAD University), and her predecessor, Arthur Lismer (1885–1969). Royle encouraged Colville to consider art as a profession. Colville was planning to study law and politics, and had been accepted into Dalhousie University in Halifax with an entrance scholarship. Royle secured an equivalent scholarship for Colville at Mount Allison, and in September 1938 he started there in a class of ten students.

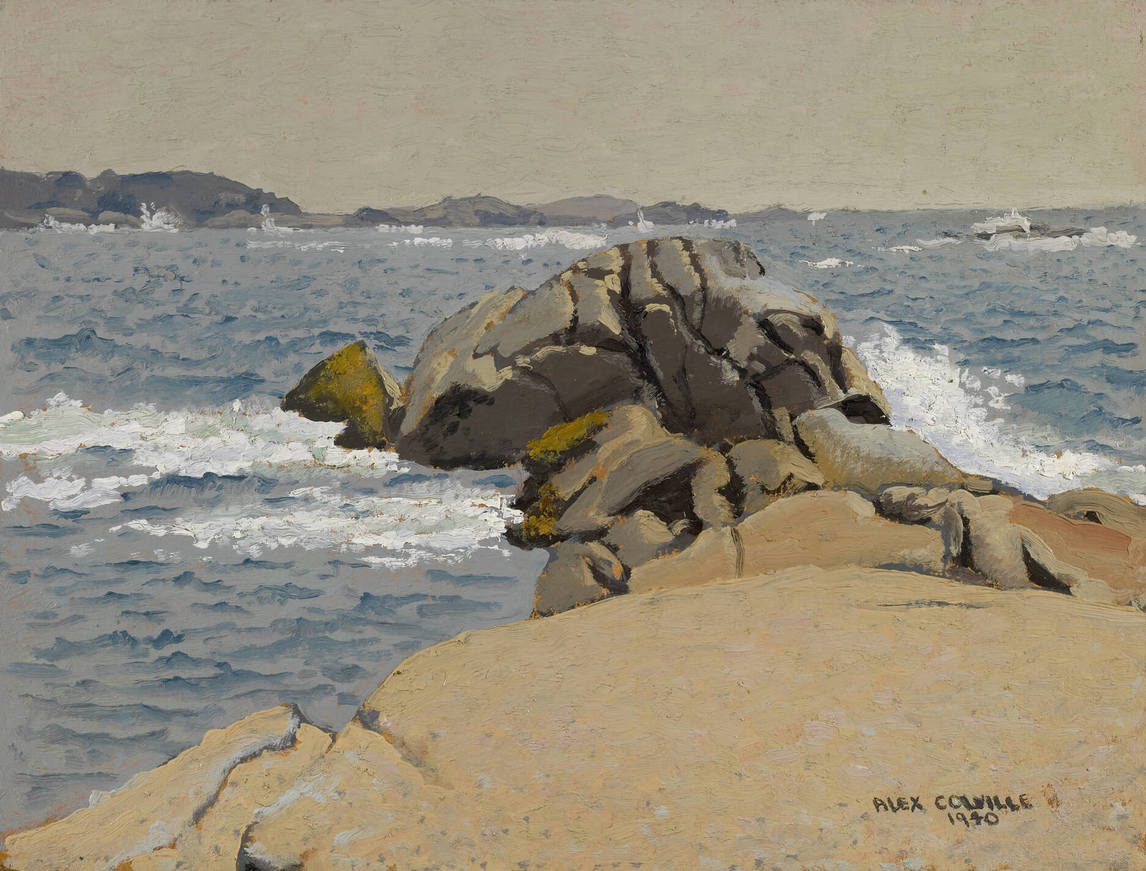

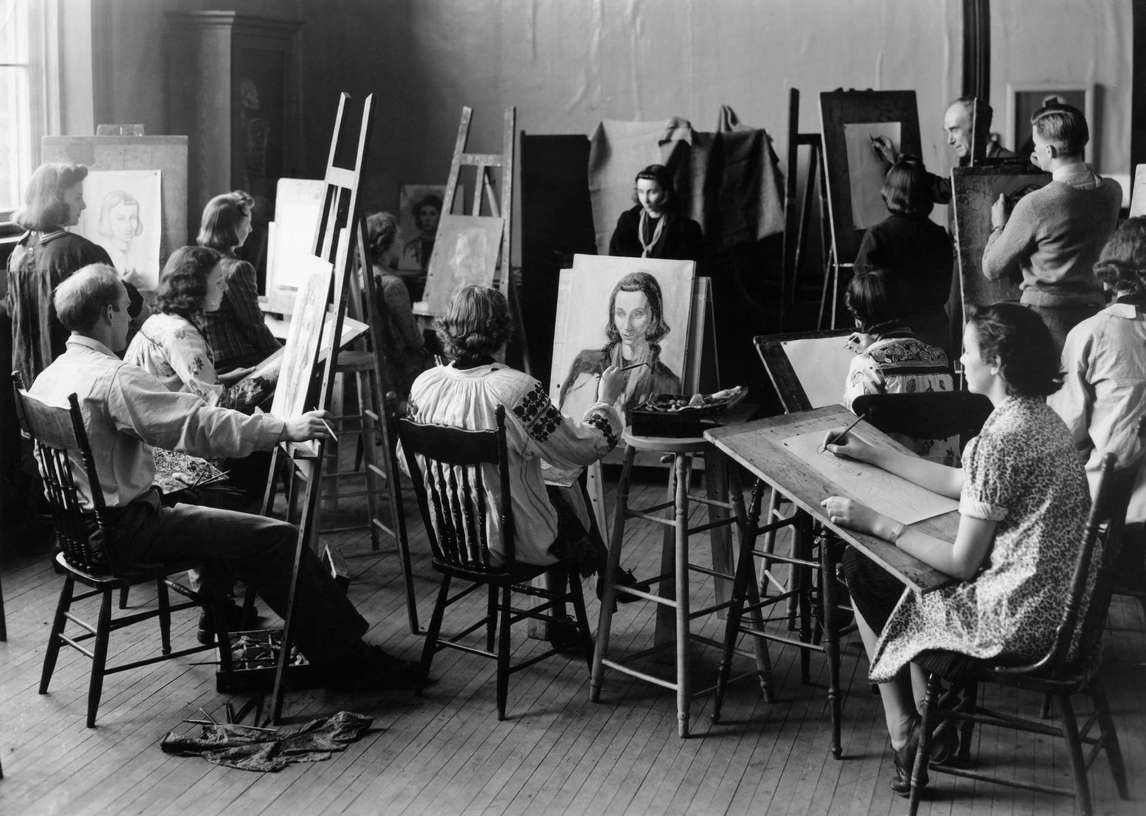

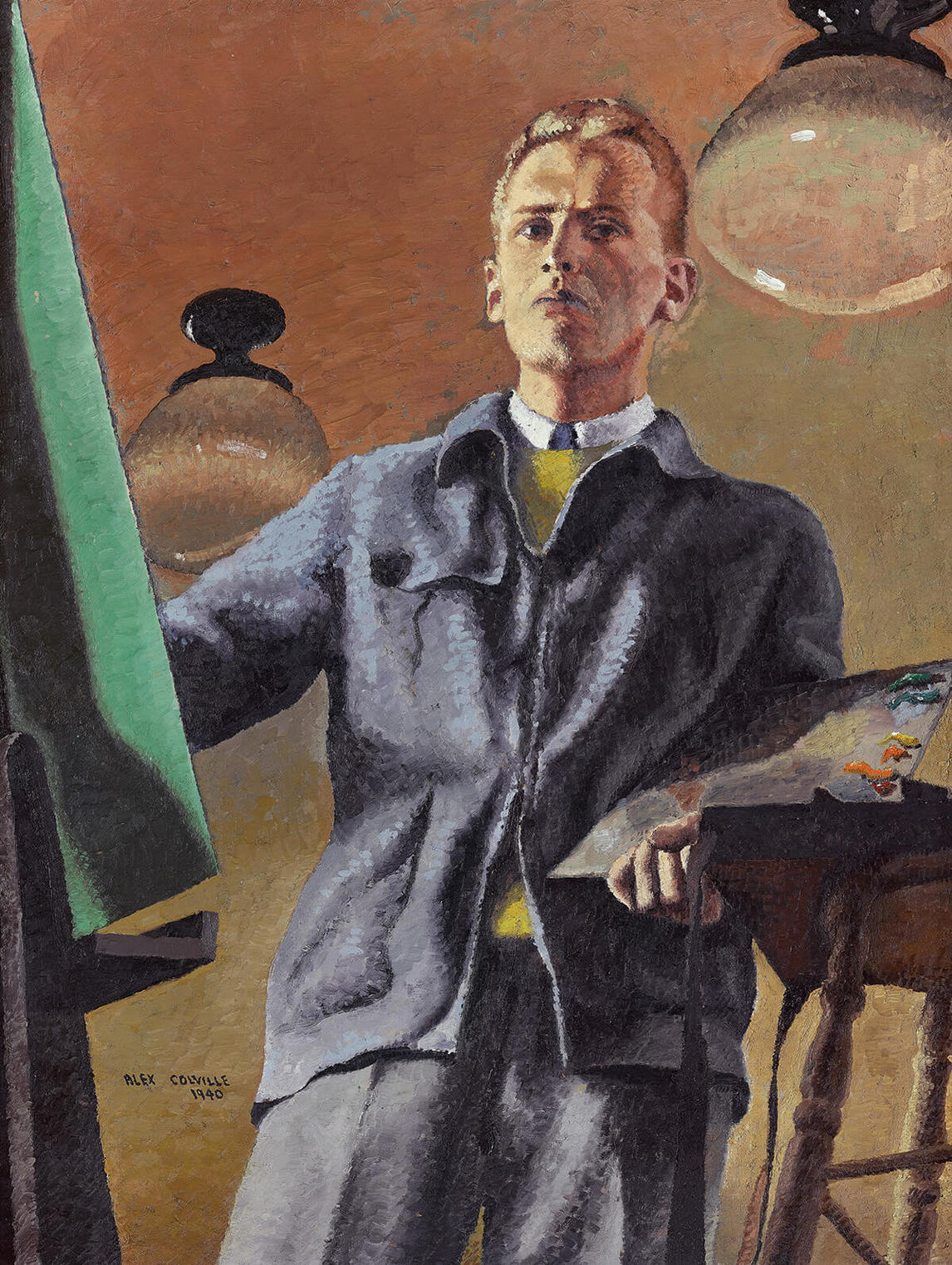

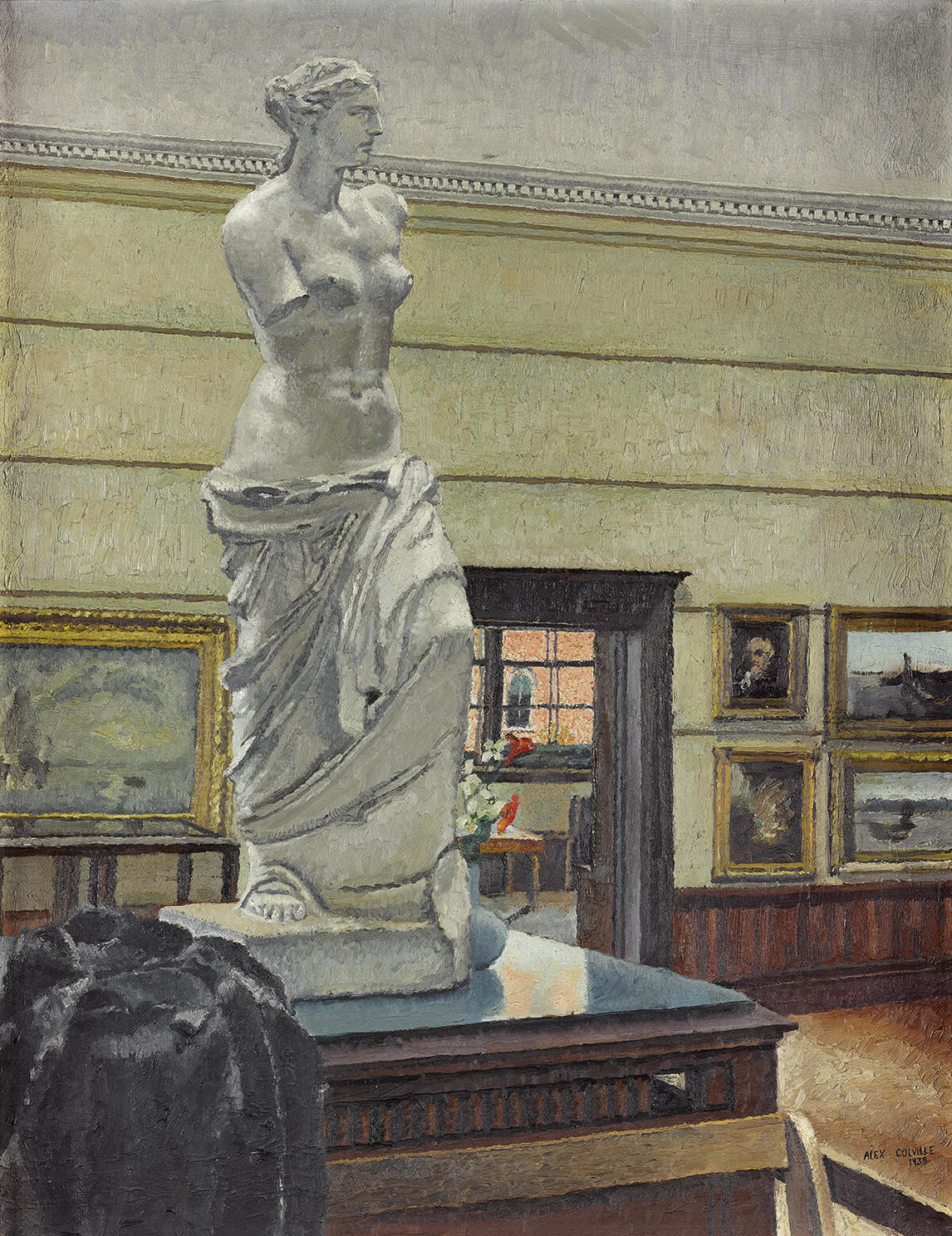

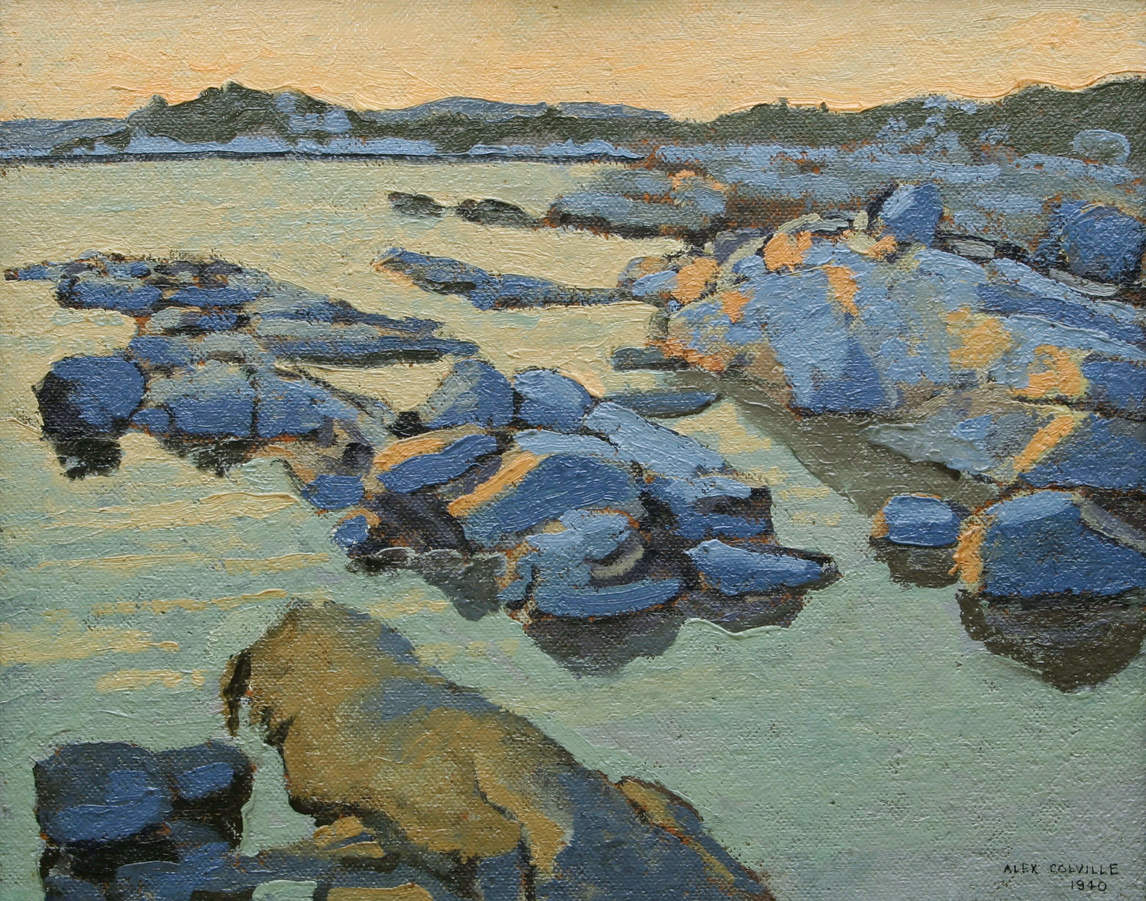

The school’s curriculum under Royle was quite traditional. It focused on drawing and painting from life and copying from classical casts and nineteenth-century paintings and drawings held in the collection of Mount Allison’s Owens Art Gallery, which included popular Victoriana such as paintings by Tito Conti (1842–1924) and other painters of the day, as well as prints by Whistler (1834–1903) and an impressive tondo by Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898). The art school was housed in the gallery, which Royle also directed. Few paintings by Colville from this period have survived, and the ones that have display a Post-Impressionist style much influenced by Royle, as in Self Portrait, 1940, and Interior Owens Art Gallery with Figure, 1941.

Colville had his first successes as an artist while enrolled at Mount Allison, with works included in exhibitions of the Art Association of Montreal (now Montreal Museum of Fine Arts) in 1941 and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA) in 1942. This significant achievement must have contributed to Colville’s sense that a career in art was possible, though Colville credited a conversation with Royle he had as a seventeen-year-old high school student: “I then asked him if he thought that if I became an artist I would be poor and have a terrible time. Fortunately, he said that he didn’t think that would happen. I think I decided virtually that same day that I would be an artist.”

This was an ambitious idea in those early war years, especially in a poor region such as the Maritimes, but Colville would have seen such artists as Royle in Sackville, Miller Brittain (1914–1968) in Saint John, and Nutt and D.C. Mackay (1906–1979) in Halifax, all who exhibited nationally and internationally. Their careers made apparent that making a living as a painter was indeed possible. The Canadian art world in the interwar years was smaller and less fractured than today, with groups such as the RCA and the Canadian Group of Painters and the institution of annual group exhibitions doing much to ensure that artists across the country were aware of one another and their work.

Colville’s first-year class in 1938 included a person who became the central figure of his life: Rhoda Wright. Rhoda, born in 1921, was from Wolfville, Nova Scotia. Originally friends, their relationship developed slowly. “We met as freshman at Mount A.,” remembered Rhoda. “I really didn’t think he was any ‘great shakes,’ as they say. It took us a long time to get to know each other.” The relationship developed, however, with one memory standing out as a turning point for Rhoda:

But there was a night after we had been to a movie downtown and we came out of this old movie theatre into a very snowy winter night and there was a crossroads in the town and we had to go across there to go up York Street. Alex took my hand when we walked across. With his bare hand he held mine and we walked across. That was quite a thrill. Can you imagine that? I think, maybe, that was the beginning of the end of the platonic friendship.

The two were married in August 1942. Their decision to wed was complicated by another momentous event in Colville’s life: upon graduation from Mount Allison in the spring of 1942, he had enlisted in the First Canadian Army.

The Second World War

Colville aspired to be a war artist, as such Canadian painters as A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) and Arthur Lismer had been in the First World War. However, the official war art program was yet to be instituted when Colville enlisted, and he spent the first two years of his service in non-combatant roles, receiving a commission as a lieutenant in September 1943. He served in Fredericton, New Brunswick, and then in Camp Petawawa, Ontario. In May 1944 he was assigned to London, England, where he was made an official war artist. He spent the next two years documenting Canada’s war effort in England and on the continent.

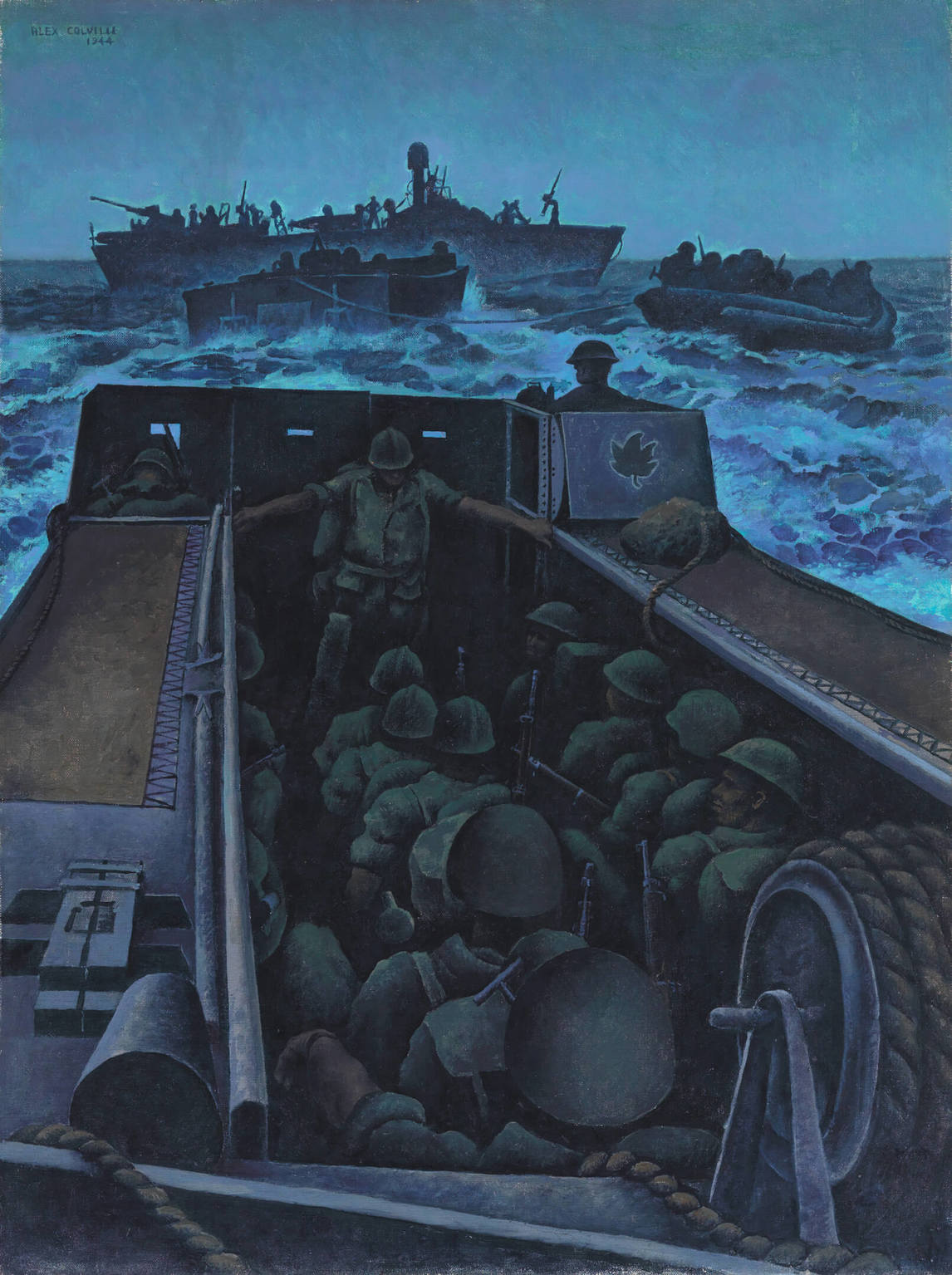

Colville was first stationed with the Royal Army Service Corps in the Northern England county of Yorkshire, where he made sketches of the men and equipment being marshalled to send to France in support of the D-Day invasion. Six weeks later he was assigned to the navy and sailed to the Mediterranean aboard the HMCS Prince David, a ship carrying troops for Operation Dragoon, the allied landing in Southern France that followed the successful D-Day landings. He was aboard the Prince David for six weeks, after which he returned to England to work up finished paintings from his sketches from Yorkshire and the Mediterranean, as in Convoy in Yorkshire, No. 2, 1944. In October 1944 he joined the Third Canadian Infantry Division, where he remained until September 1945. As part of his service he was present at the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, witnessing first-hand the extremes of inhumanity to which Nazi ideology had led Germany. In October he was assigned to Ottawa, where he spent the last six months of his army career creating oil paintings from his sketches and watercolours.

The war had a great impact on Colville, but he always resisted notions that his view of the world was overly coloured by his wartime experience. Author and curator Tom Smart, in Alex Colville: Return, makes much of the trauma of the war and read into Colville’s paintings a response to horror. “When Colville entered the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp at the end of the war, his artistic sensibility was fixed, petrified by the defining moment of witnessing the mass graves,” he writes. “Whether the distance from Bergen-Belsen is measured in days, years or half a lifetime, the vividness of his experience continues to haunt Colville’s work.” Colville, however, had a very different idea of the war’s impact on his art, telling Toronto Star critic Peter Goddard that Smart’s reading of his art as a “visual testimony” to the horrors of war was “over emphasized.” Resisting any characterization as a victim, he continued: “The war had a profound effect on me. But it was all about the action of war. All my instincts as a kid were toward action. And war is action to the nth degree. It’s amazing in a sense how tough people are. I wasn’t sickened or horrified or anything.”

Perhaps as a refuge he chose to remember the war in its action—the convoys, heavy equipment, and vehicles of all descriptions (as in The Nijmegen Bridge, Holland, 1946) and in the years of training and preparation that preceded the months of actual fighting after D-Day (as in Landing Craft Assault Off Southern France, 1944). Bergen-Belsen was undoubtedly impactful for the young Colville—the sheer scale of the horror was numbing. As he put it, “Well it was kind of chilling. I remember the grave with 7,000 bodies in it and so on, still open. Pretty terrible business.” Many critics, including Tom Smart, feel that chill in all of Colville’s postwar work.

Mount Allison

Upon his demobilization from the army, Colville was offered a faculty position at Mount Allison University in New Brunswick. This attracted him because, as he wrote, “I decided to settle down in Sackville where I could have the time, the feeling of belonging, the solitude, and, above all, the freedom from distraction which I needed to become oriented as an artist.”

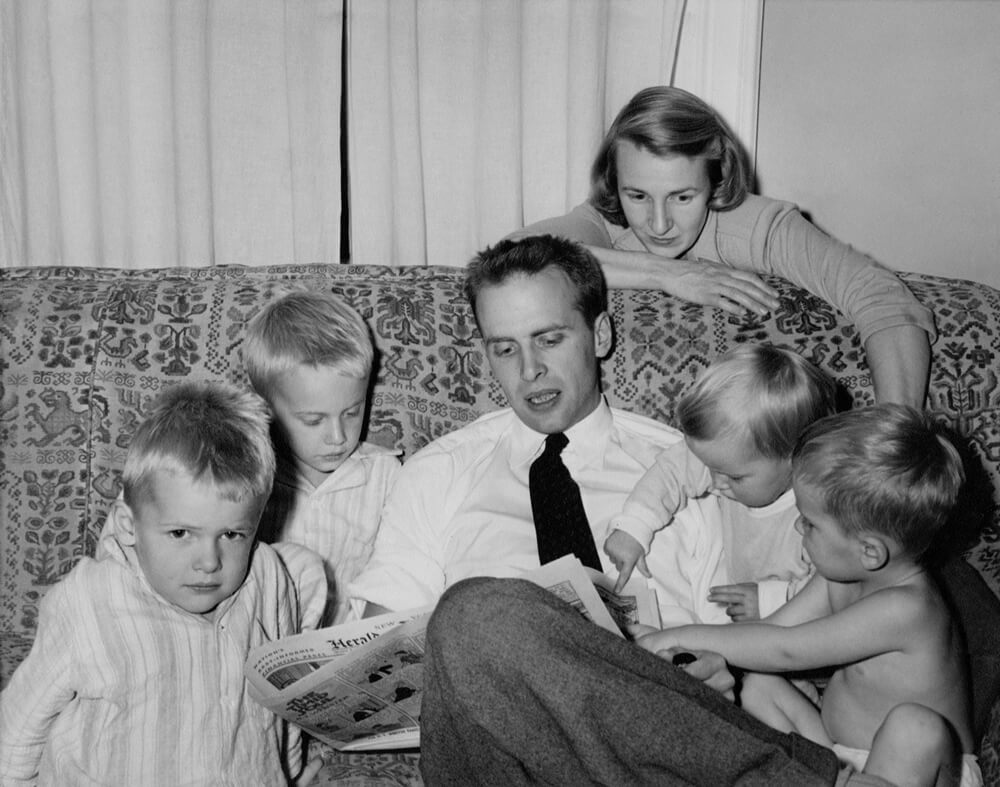

The Colville family settled into Sackville, with Alex teaching and Rhoda staying at home with the children. They had two by this point; their eldest, Graham, had been born in 1944 and their second son, John, in 1946. Charles was born in 1948 and their only daughter, Ann, in 1949. While Rhoda dedicated herself to family, she maintained an interest in creative pursuits, notably playing music and writing playful poems that marked events in the lives of her family and friends.

Initially, Colville found little time for his own creative endeavours as he concentrated on his teaching career and the growth of his young family. His few paintings of the period, for example, Windmill and Farm, 1947, were landscapes of the environs around Sackville, depicting farms, horses, and the bridges over the Tantramar Marsh. They hark back to much of his work during the war, providing straightforward renderings of what he saw around him. Student accounts reveal Colville as a meticulous teacher, one focused on skills development and observation. His practice of looking for inspiration in his immediate surroundings was inculcated in such students as Mary Pratt (b. 1935), Tom Forrestall (b. 1936), D.P. Brown (b. 1939), and Christopher Pratt (b. 1935). As Mary Pratt remembered, “He showed me you could just look at the world in its wonderful simplicity and find in that simplicity lots and lots to think about.”

However, the time that teaching took from painting frustrated Colville. According to Helen J. Dow, a colleague at Mount Allison who wrote the first major monograph on Colville, at one point he even considered giving up painting to become an architect. A major commission from Mount Allison in 1948 forestalled this, and he completed the large egg-tempera-on-linen painting over that year. This mural, called The History of Mount Allison, 1948, was his largest and most complex work to date. It served to assuage his frustration, as he was able to feel that painting could contribute to his family’s income. Architecture, while an abiding interest, ceased to be discussed as a possible career. In 1951, Colville had a solo show at the New Brunswick Museum in Saint John. Beyond being his first solo show, this exhibition was notable for several reasons, as it marked the first time his work was written about in newspapers, his first public lecture on his art, and one of his first sales to a public art gallery: the 1950 painting Nude and Dummy, to the New Brunswick Museum.

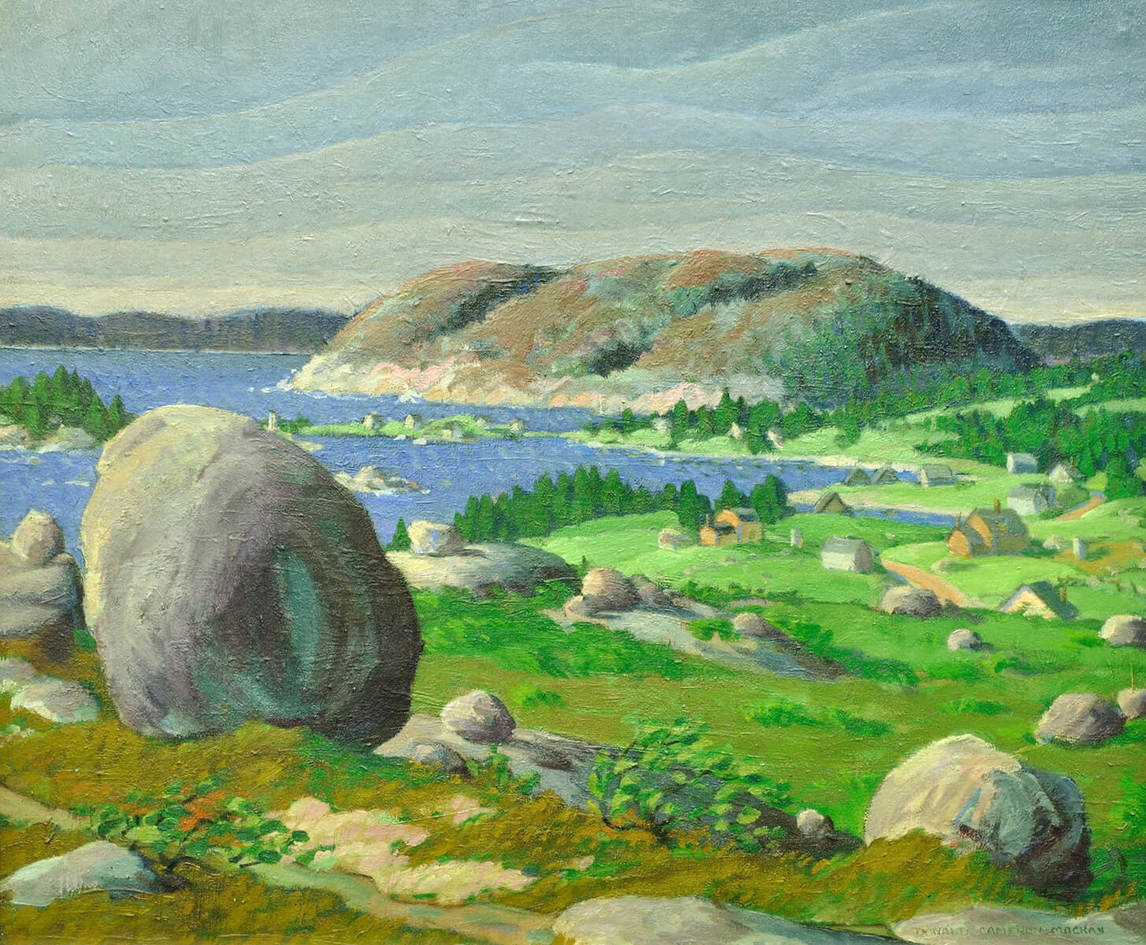

Colville always upheld that Nude and Dummy was his first mature work: it represented what he considered to be his own style and was a subject matter fully of his own invention. It seemed to mark a change for Colville, a sign that he had arrived as a painter in his own right. As he maintained, “I was therefore thirty years old before I did anything worthwhile.” His Post-Impressionist landscapes of his student days, and the illustrative approach of his war art, provided a strong foundation for this development, but one only has to compare this painting with paintings such as Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia, 1940, or The Nijmegen Bridge, Holland, 1946, to see that in these works he had not achieved his mature style.

Colville exhibited regularly throughout the 1950s, with shows at commercial galleries in New York and Toronto, as well as at Hart House Gallery at the University of Toronto (now part of the Art Museum at the University of Toronto). Canadian galleries, including the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, and the Art Gallery of Hamilton, began to acquire his work. His paintings began to be associated with the magic realists, particularly his works featuring nude female figures in non-specific landscapes and settings, such as Nudes on Shore, 1950, and Four Figures on Wharf, 1952. Though these figures were mostly invented, his wife, Rhoda, began to appear in more of his paintings, such as Woman on Wharf, 1954, or Woman at Clothesline, 1956–57. She soon became a key subject, one extending throughout his career. It was natural for Colville to use his family as models, because of his avowed desire to use his immediate surroundings as subject matter.

Other contemporaneous works, such as Child and Dog, 1952, Soldier and Girl at Station, 1953, and Family and Rainstorm, 1955, show the themes and direction he would pursue for the next six decades: his family, his home, the environs of Sackville or Wolfville (or, very occasionally, other places he lived, such as Santa Cruz, California, or Berlin). The relationships between humans and animals, and men and women, also become predominant themes. These binaries were important for Colville: “The painting starts to work, sometimes, when two elements appear to throw light on each other.” Colville had found his voice.

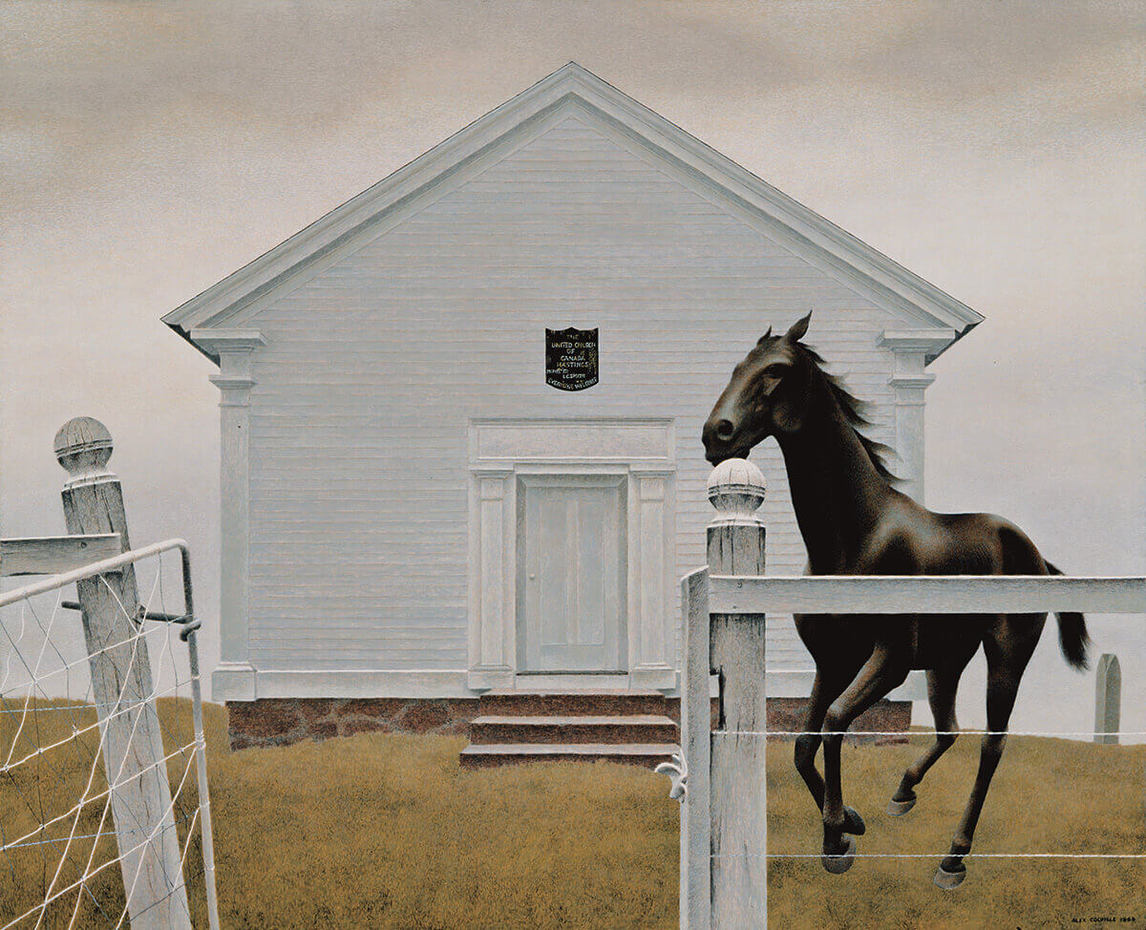

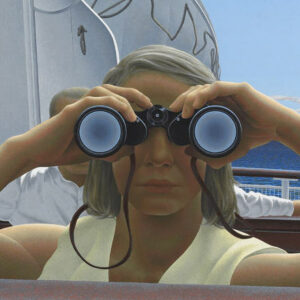

By the early 1960s Colville’s career was thriving, with regular sales and exhibitions, and he decided to resign from Mount Allison in 1963. He and Rhoda stayed in Sackville until 1973, and he remained productive during these years with important exhibitions, such as his inclusion in Canada’s entry at the 33rd Venice Biennale in 1966. He continued to have solo shows in New York and in 1969 had his first solo exhibition in Germany. Some of his most iconic works were created during this period, including To Prince Edward Island, 1965, with its image of a female figure seeming to look straight out at the viewer through a pair of binoculars, and Church and Horse, 1964, with its wild black horse running across the picture frame. Colville said of this work, “I did this painting a few months after the assassination of President Kennedy. It’s curious how one’s mind gets filled up with images, but I recall watching the funeral, as I suppose many people did, with great interest, and being impressed with the black, riderless horse, and I suppose that this has some kind of crazy connection with my having done the painting.”

In 1965 Colville was commissioned to design circulation coins commemorating Canada’s centennial. This commission meant a lot to the artist, as it represented an unexpected reach to the largest possible Canadian audience—his artworks became part of the daily life of all Canadians for decades. Accolades continued to accumulate for Colville throughout the 1960s, with election to the Order of Canada in 1967 and three honourary degrees: from Trent University in Ontario in 1967, Mount Allison in 1968, and Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia in 1969. The University of California, Santa Cruz, named him a visiting artist and he spent the 1967–68 school year living in California, where he considered staying. However, the lure of his settled life in Sackville was too strong. His London dealer, Harry Fischer, encouraged Colville to move to London, England (which he would not do), and in 1971 helped arrange for a residency in Berlin. This Colville gladly accepted, but not without reservations: although the offer was to work abroad for one year, he negotiated a six-month term in order to reduce the time away from his studio.

Nova Scotia and Later Life

In 1973 Alex and Rhoda moved to Wolfville, Nova Scotia, a small university town much like Sackville. The couple moved into Rhoda’s childhood home, a large house on the main street, across from Acadia University. Colville’s success continued, with commercial and public shows throughout the 1970s and 1980s and more professional accolades: he received the Canada Council Molson Prize in 1974 and honourary degrees from universities across Canada, including Acadia University in 1975. He was the subject of museum shows in Canada, Germany, and the Netherlands, and in 1978 began his long professional relationship with Toronto’s Mira Godard Gallery. Previously, Colville had multiple dealers: the Banfer Gallery in New York and Marlborough Fine Art and Harry Fischer in London. But when he joined Mira Godard’s stable of artists, he received almost uninterrupted solo representation by Godard (he briefly left the gallery in the 1990s to be represented by the Drabinsky Gallery, but returned to Godard after the short-lived experiment).

In 1981 Colville was named chancellor of Acadia University, a post he held for ten years. His first museum retrospective, curated by David Burnett and accompanied by a monograph, was mounted in 1983 by the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), Toronto. It subsequently toured across Canada and to Germany. His work was shown in Asia in the mid-1980s, and he continued his commercial career with shows in Toronto and London. In 1991 he was named to the board of directors of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, and in 1993 Brian Mulroney, then prime minister of Canada, named him to the Privy Council for Canada, an entity set up to advise the prime minister. Colville painted and made prints, and notable images such as French Cross, 1988, and Horse and Girl, 1984, were created in this period. His style remained the same, a steadfast approach to technique and content that he sustained throughout his career. Colville’s consistency was a hallmark of his work—his style, once achieved, remained recognizably and uniquely his own. That consistency, however, was not always valued.

The 1980s were a period in which Colville was on the receiving end of poor reviews. The Globe and Mail said of his 1983 retrospective, “Like many other mediocre art works similarly wrought with time-consuming care and obsessive attention, these paintings invite a certain kind of admiration—the kind we willingly accord a painting of the Last Supper on a thumbtack, or the precisionist kitsch of Salvador Dali.” An article in Canadian Forum attacked Colville’s status as the “Head Boy of Canadian Painters.” In part, this criticism may have been based in Colville’s lack of interest in current debates surrounding postmodernism, sexual politics, or overt political commentary—all of which were filling the galleries of the day, usually in photographic, video, and installation formats. In the eyes of many critics, Colville’s work was irredeemably conservative.

This continued well into the 1990s, with dismissive reviews and articles appearing regularly in response to a Colville exhibition. No one was more blunt, in print at least, than Globe critic John Bentley Mays. For instance, he described Colville’s Verandah, 1983, as, “a scene so banal and airless it leaves the viewer gasping. BUT this airlessness brings us to another of Colville’s manifest powers: his ability to keep making pictures of incomparable emptiness, coldness, emotional desolation, year after year, with no advance, experiment, hesitation, questing. No artist’s work seems more stagnant, less vital.”

However, Colville had his supporters in the art world and in the public who seemingly never lost their fascination with him. A 1987 Canadian Art magazine cover story on Colville went out of its way to refute earlier criticisms, noting the very comments mentioned above.

As the twentieth century drew to an end, the good reviews, honours, and accolades far outnumbered the criticisms. In 1997, Colville, who in 1951 had described himself as a “conceptual” rather than “perceptual” artist, received an honourary degree from the hotbed of Canadian conceptual art, the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. From 1993 to 2003 Colville was the subject of four museum exhibitions, two of which toured the country, including the last of his museum exhibitions mounted in his lifetime, Alex Colville: Return, organized by the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. Until 2005 it toured to Halifax, Fredericton, Toronto, London, Saskatoon, and Edmonton. In 2003 Colville received the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts, as well as the Order of Nova Scotia. He continued to paint and had five exhibitions at commercial galleries between 2002 and 2010.

In 2012 he suffered two major losses: in late February his middle son, John, died of heart failure, and on December 29 Rhoda passed away. During the summer of 2013, when he was 92 years old, Alex Colville died at home in Wolfville. Rhoda, his wife of seventy years, died at 91. “True love is never long enough,” wrote the Ottawa Citizen’s Peter Simpson. “Surely Alex’s heart was broken, and less than seven months later, on July 16, 2013, his heart stopped beating.”

In 1951 at a lecture in support of his first solo exhibition, Colville said about the audience for painting: “We can only conclude that our audience, that our public, must consist of those people from all classes who are capable of experiencing painting. We must acknowledge the worthiness of this small public and hope, as I believe, that it is steadily growing, not only in numbers, but in understanding and appetite. These are the people we paint for.”

Colville’s hopes for an expanded audience were prescient: Alex Colville, the largest exhibit of the artist’s work ever mounted, opened at the AGO in August 2014. It became the best-attended Canadian exhibition in the AGO’s history and its first Canadian show to be in the gallery’s top ten–attended exhibitions. It subsequently travelled to the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, where it drew large audiences and met with critical praise.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements