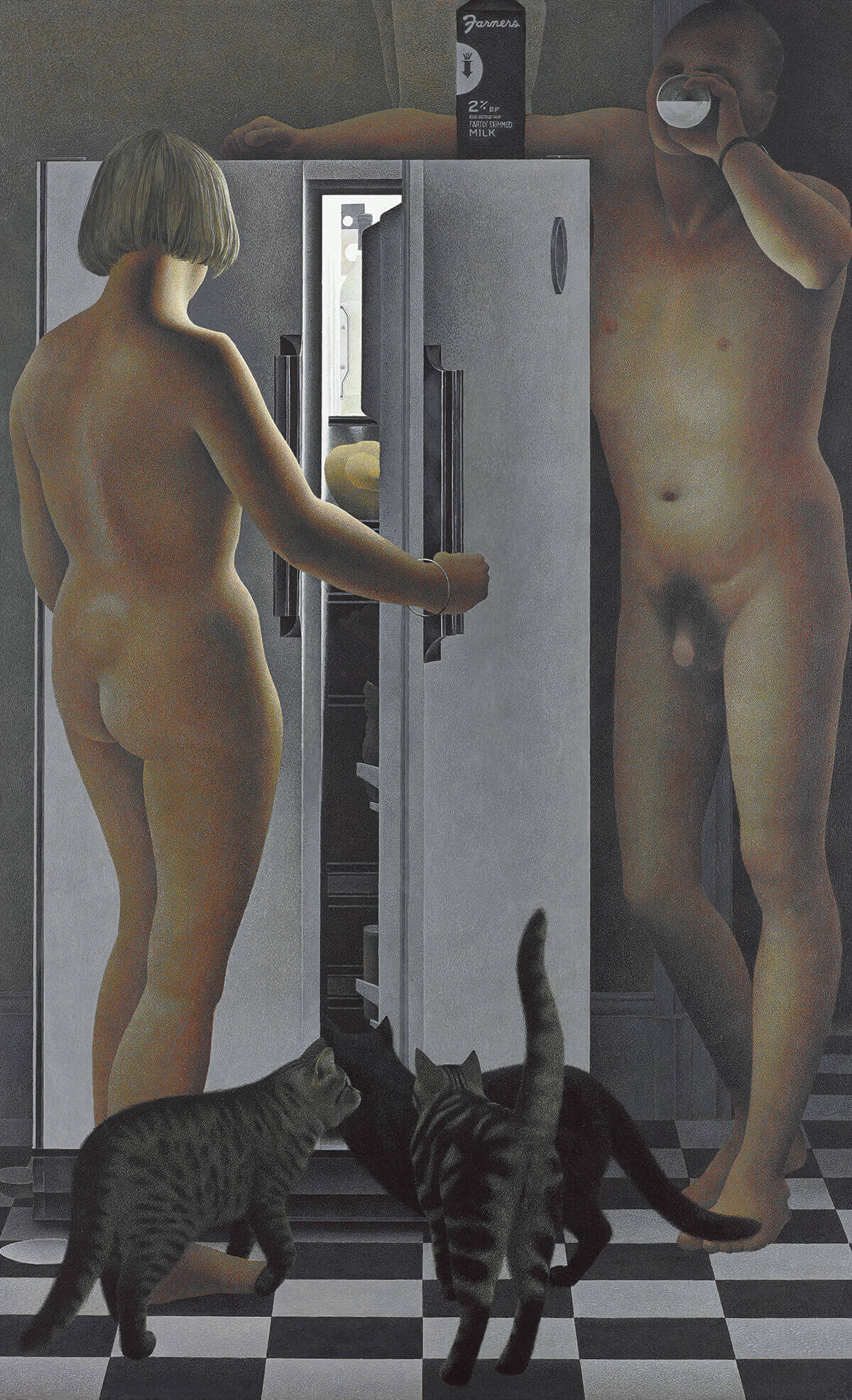

Refrigerator 1977

Alex Colville, Refrigerator, 1977

Acrylic polymer emulsion on hardboard, 120 x 74 cm

Private collection

In 1970s Canada, Colville’s most controversial work, Refrigerator, shocked with its frank depiction of a nude, middle-aged couple. As art historian Mark Cheetham writes, “For some viewers, this ‘familiarity’ is taken too far, and Colville has been criticized for the nudity here (apparently they are more concerned with male than female nudity, an ancient tradition in art).” Even today, the full-frontal nudity of the image is screened out by the filters of most internet search engines. It remains inappropriate, apparently, forty years after its creation.

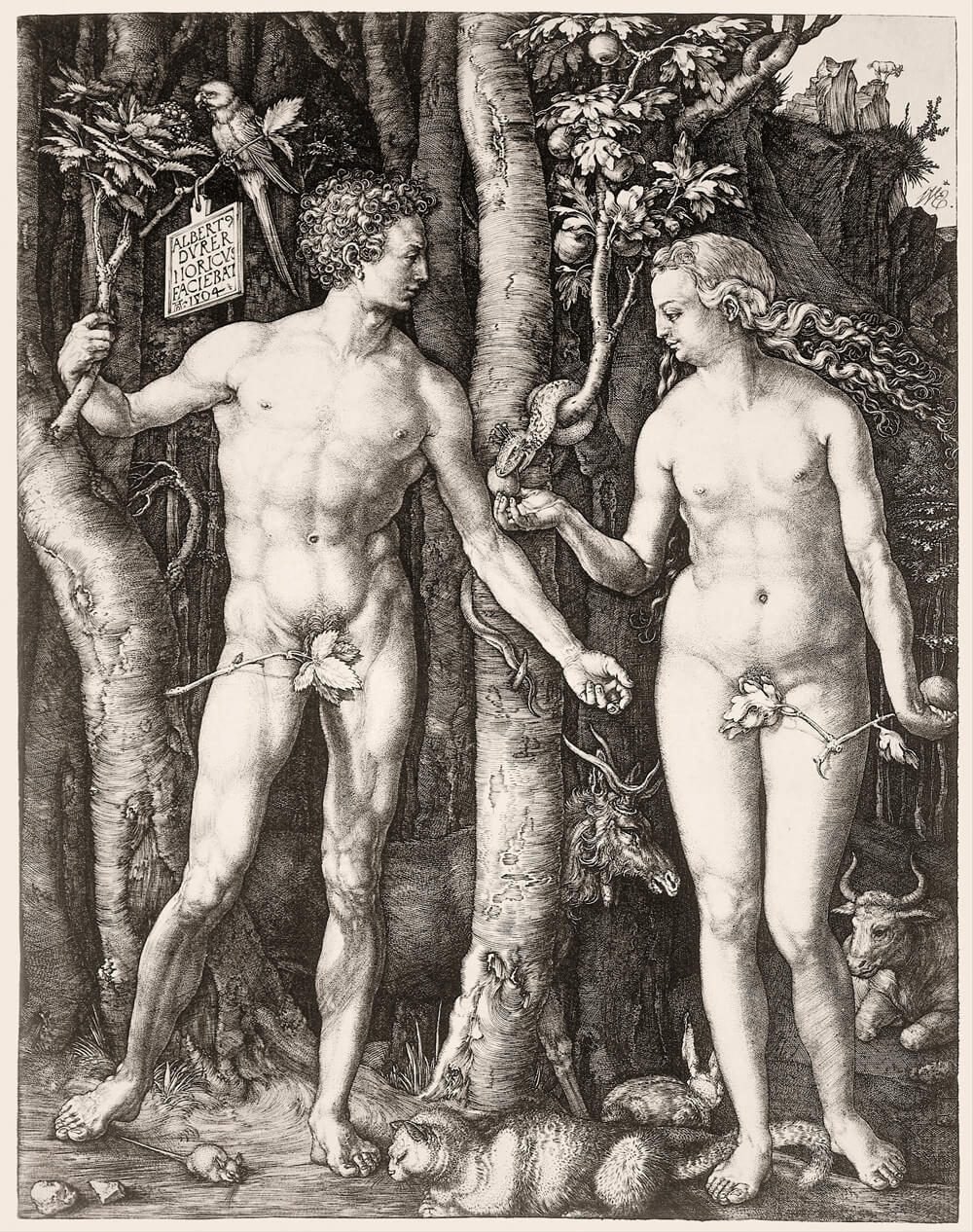

The painting depicts a nude couple in a dark kitchen standing around their fridge. The man drinks a glass of milk; the woman is at the open door, as if considering her options. Three cats gather at their feet, hoping for some food or drink, or merely attention. Historically in Western painting, the female nude is ubiquitous. However, the full-frontal male nude, without the convenient fig leaf familiar from early depictions of Adam and Eve, is decidedly less so. Here Colville presents a domestic scene that, despite its Adam-and-Eve allusions, is distinctly contemporary.

As with all of Colville’s images this one lacks extraneous detail—no notes or drawings on the refrigerator door, no use of the fridge-top for storage. The female figure stands naturally, one hand holding the door open. The male stands beside the fridge with his arm draped across the top of it, facing the viewer. Even for a tall man, this would be an uncomfortable pose, and he would have to be more than two metres tall to manage such a contortion. But the image feels right, despite its physical incongruities.

The man’s pose is not from life, but from compositional necessity. His outstretched arm visually links with the woman’s head, and the cats create a horizontal line across the bottom of the picture, leading to the male figure, which completes the “frame” on the right-hand side. The rectangle created by the bodies mimics that of the refrigerator, the glowing “hearth” around which this domestic scene centres.

The relationship between husbands and wives is a constant theme in Colville’s painting, with those figures almost always depicting himself and his wife, Rhoda. Here the figures are self-sufficient, but necessary to each other—the feeling of ease would be lacking without one of the human figures. The contorted male pose only seems normal in the context of the compositional balancing of the female figure. That the woman provides the stability is no surprise, given Colville’s body of work—as with After Swimming, 1955, the female figure is the anchor, while the male figure is off-balance, steadied only by his relation to the female.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements