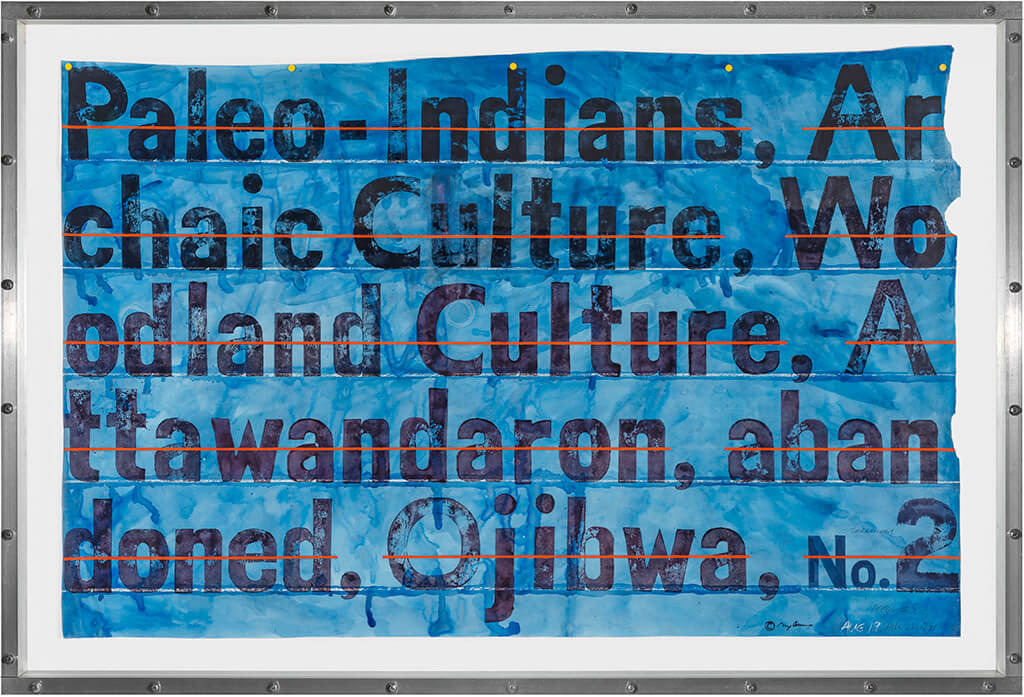

Deeds #5 1991

Greg Curnoe, Deeds #5, August 19–22, 1991

Stamp pad ink, poster paint, graphite, watercolour on paper, 110 x 168 cm

Winnipeg Art Gallery

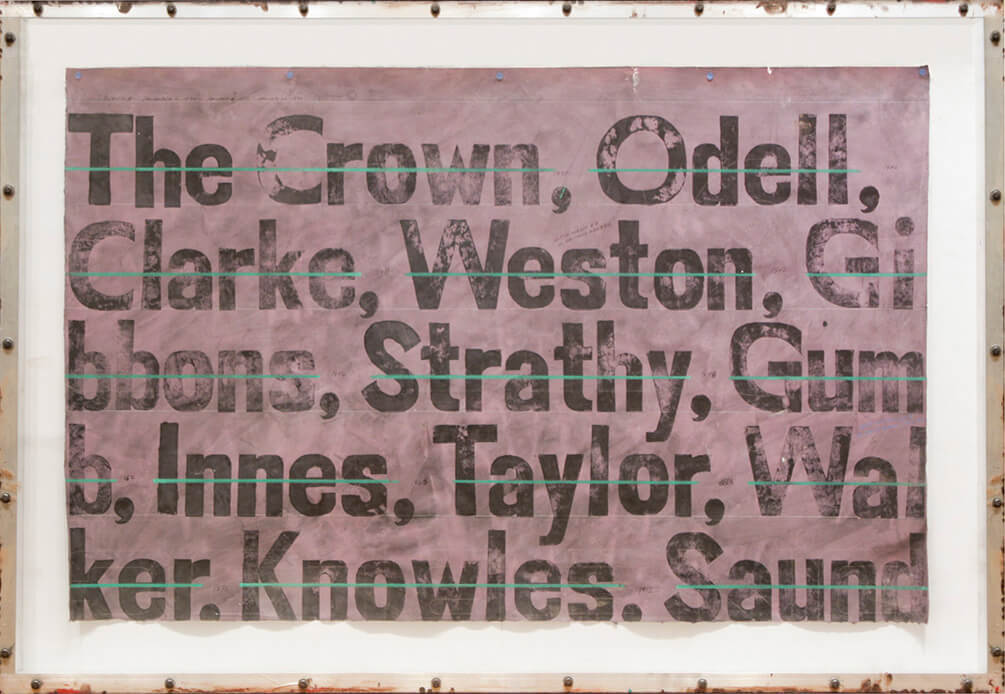

Greg Curnoe spent much of the last two years of his life tracing the history of his property at 38 Weston Street in London, Ontario, by searching records (deeds and abstracts of the records) and interviewing descendants of European settlers and First Nations inhabitants. This work, the last in a series of five large text works, documents the earliest history, from the Paleo-Indian Period (8600 BCE) to the “No. 2 Surrender” to the Crown of the Ojibwa lands in Southwestern Ontario in 1790.

Curnoe described his startling realization: “We live in a culture where pre-existing cultures lived and live. They have survived in isolation from the culture of the City of London, both within the city and in areas of original settlement that date back to around 1690, fifteen miles away. They have been omitted from most books of local history.” In an ironic twist, the anti-American and Canadian patriot was forced to confront the “cultural imperialism” of his own predecessors.

Having documented his research on his newly purchased computer, he found that he had enough material for a book. After his death, his editors divided the original material into two volumes: Deeds/Abstracts (1995), the history of his lot, and Deeds/Nations (1996), an alphabetical listing of over one thousand First Nations individuals who lived in southwestern Ontario between 1750 and 1850. As archaeologist Neal Ferris explained, “Until Greg Curnoe’s monumental effort to track down, follow up and piece together the personal biographies and family histories of the Native people signing the southwestern Ontario land surrenders of the 18th and 19th centuries, little had been done to make sense of who most of those signatories were, or their roles in local and regional communities.”

The artist had extended his notion of regionalism from his backyard and the here and now to what had happened in his region for thousands of years. As he wrote, “I have felt the power of many details adding up to an understanding of the ground I am standing on. It is an understanding that is new to me.” We can only guess at what might have happened next in his artistic production as a result of this new insight.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements