While Halifax’s history stretches back thousands of years as a centre of Mi’kma’ki, its colonial origins date to the mid-eighteenth century when it was established in 1749 as a British fort. It remains a military centre, home to Canada’s East Coast Navy and the shipyards that sustain it. It is the capital of Nova Scotia and the largest, and richest, city in Atlantic Canada. It attracts thousands of newcomers every year: tourists, students, and economic migrants from across the region, the country, and the world. Halifax is a city of education, home to five major universities as well as being the centre for health care education and research in eastern Canada. It has a thriving arts community in the visual arts, music, literature, theatre, and film. It is a city that often seems to be in flux. Like the tides that have shaped its landscape, Halifax’s fortunes ebb and flow, its art history, like so much of the rest of its history, a series of arrivals, departures, and returns.

Pre-colonization

The area that is now known as Halifax has always been an important part of Mi’kmaw life and culture. K’jipuktuk, “the Great Harbour,” was integral to the coordinated movements of a people who moved across their lands in harmony with the seasons and the rhythms of the animals that were their food sources. Inland were caribou and moose, and the shores of K’jipuktuk abounded with shellfish, seabirds, and, just offshore, teeming shoals of fish. The numerous rivers that fed the harbour were magnets for Atlantic salmon that in hundreds and thousands thronged up even the smallest creeks. “[The] food supply [for the Mi’kmaq] was bountiful, dependable and extremely healthy,” Mi’kmaw historian Daniel N. Paul writes, “and materials needed to construct snug wigwams and make clothing suited to the seasons of Mi’kma’ki were readily available.”

The Mi’kmaq had a sophisticated visual culture based on the creation of objects that united beauty and utility. Carving, quilling, beading (using beads made from shells and other natural materials), and weaving were among the techniques practiced by Mi’kmaw artisans before sustained European contact. “In Mi’kmaq and Maliseet [Wolastoqey] communities recognition and support has always been given to creative expression, People with skills in dance, song, storytelling, and in the creation and decorating of objects have always been appreciated,” observes Indigenous curator Viviane Gray. As in many cultures, there were gender-based differences in labour roles. For instance, Paul tells us, men hunted and women made things.

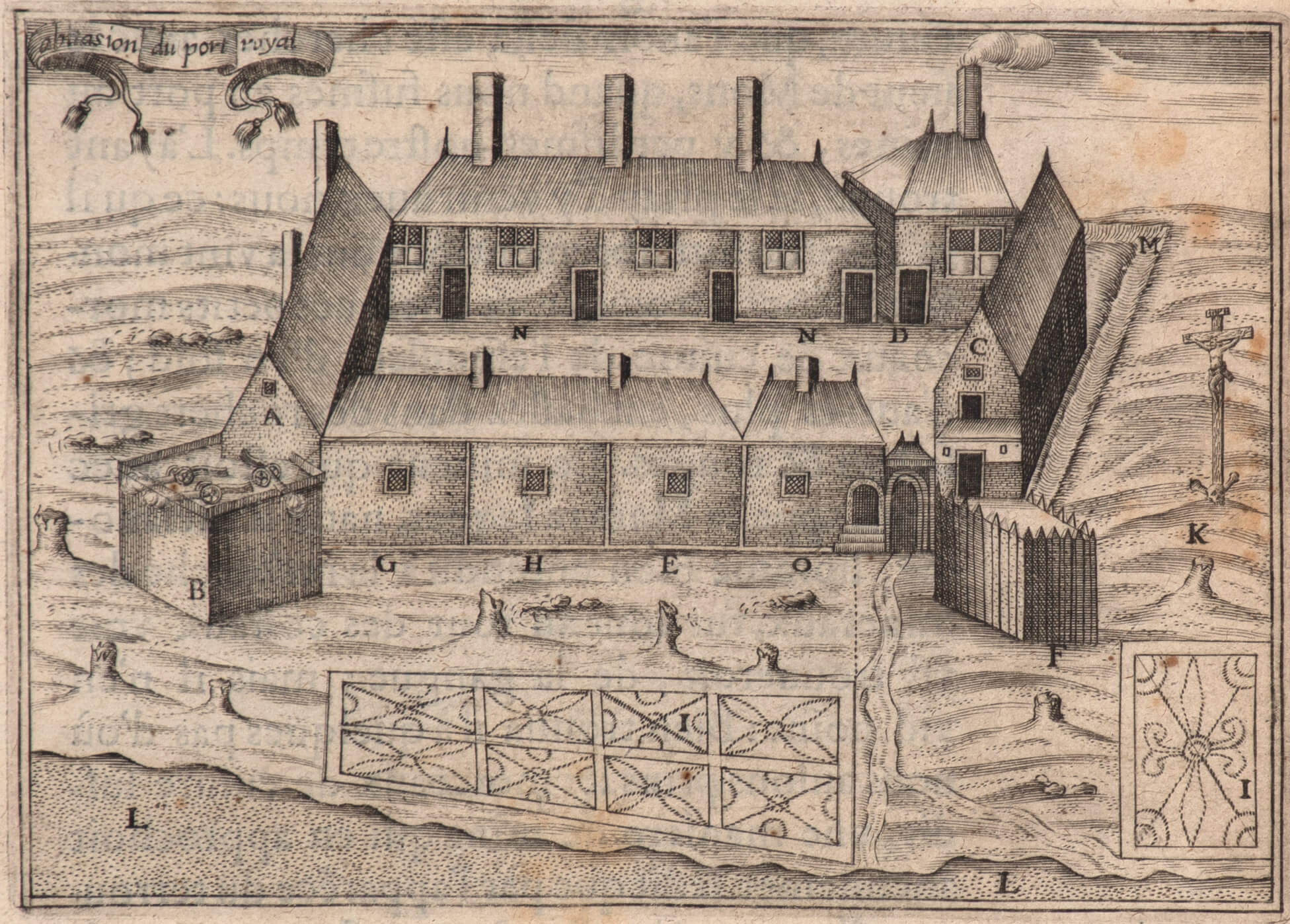

Europeans first came to live in the vicinity of K’jipuktuk in 1605, when the French explorers Pierre Dugua de Mons (c.1558–1628) and Samuel de Champlain (c.1567–1635) established the settlement of Port-Royal near present-day Annapolis Royal on Nova Scotia’s Bay of Fundy coast. But that was by no means the first time Europeans and the Mi’kmaq had been in contact. Basque fishermen had been using K’jipuktuk as a stopping place for at least a hundred years before the French settled down on the opposite side of what the British would eventually name Nova Scotia, and Vikings had been known in Mi’kmaw territory five hundred years before that.

Early European visitors noted the diverse range of art practices by Mi’kmaw artisans. In 1606 French explorer and writer Marc Lescarbot (c.1570–1642) noted that the Mi’kmaq pursued “the industry both of painting and carving, and do make pictures of beast, birds, and men, as well in stone as in wood.” Mi’kmaw visual culture was expressed in objects used by the community, either as decoration or as tools. Because it was largely made from ephemeral natural materials, few examples of pre-colonization Mi’kmaw art survive, and none can be firmly attributed to having been made in K’jipuktuk. For the Mi’kmaw artisan, it seems, an object was beautiful when it was used. There was no attempt to create objects that would last forever—when a basket wore out, for example, one made another. Objects were ephemeral; the tradition endured.

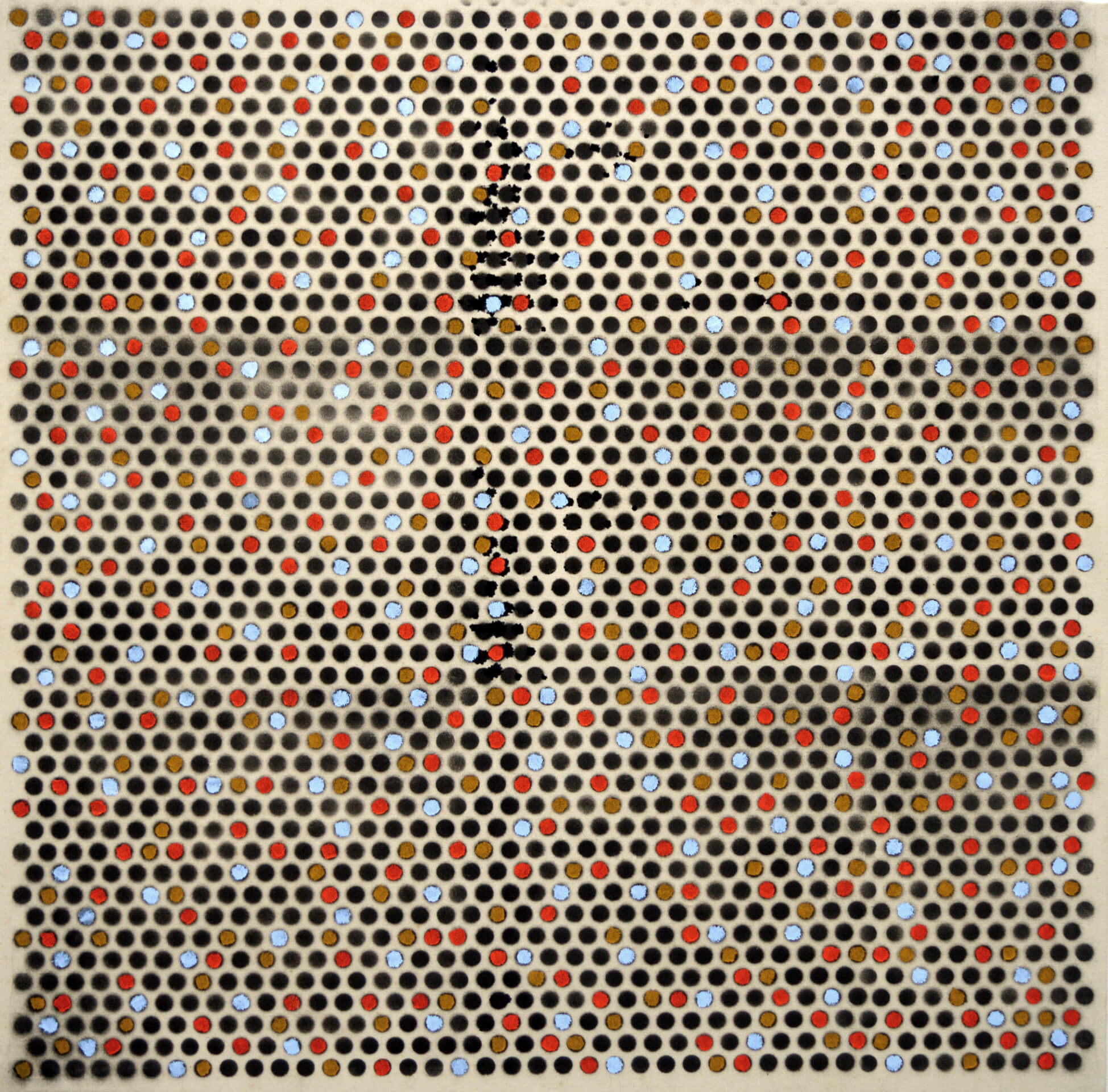

The fruits of that tradition can be seen in the basket work of contemporary Mi’kmaw artists such as Ursula Johnson (b.1980), and in the use of quillwork by those such as Mi’kmaw artist Jordan Bennett (b.1986) and the collective of Mi’kmaw women who call themselves “the Quill Sisters” (Cheryl Simon, Melissa Peter-Paul, and Kay Sark). Bennett has described working with quillwork as a conversation with the past: “There was a way to pass on this language, and it is embedded in all these objects. The way I like to think of it is that the makers knew what they were doing by putting this language into objects that would then be collected. That way future generations can then see it and try to figure it out.”

Cheryl Simon, who is also a law professor and active teacher of quillwork, sees the practice as “an accumulation and an expansion of my research, and an understanding of our treaty rights, our aboriginal rights are our legal system.”

The Mi’kmaq also left a more durable artistic expression: petroglyphs, drawings etched into stone. More than five hundred can be seen in various sites around Kejimkujik National Park, on the Fundy shore of Nova Scotia. Many of these images predate colonization. The only petroglyphs observed in K’jipuktuk are now protected as the Bedford Petroglyphs National Historic Site. Located on the Bedford Barrens, the two petroglyphs—an eight-pointed star and a drawing of an abstracted human figure—are carved into a quartzite outcropping. The site was long known to the Mi’kmaq and “discovered” by local residents in the 1980s. The marker at the site acknowledges this history, declaring, “the Bedford Barrens is a special site and a place where objects of cultural significance are offered to honour our ancestors.”

Petroglyphs remain central to Mi’kmaw iconography, and they are often used in contemporary and traditional art practice. Wolastoqi artist Shirley Bear (1936–2022) from Tobique First Nation in New Brunswick started using imagery from petroglyphs in her contemporary art in the 1970s, influencing a generation of artists, including Mi’kmaw artist Alan Syliboy (b.1952): “Understanding the meaning of the petroglyphs is a whole lifetime process,” Syliboy says. “I don’t want to set myself up as some sort of expert, because they really are a mystery to me and I look at them that way. I’m searching like anybody else. I try to get them to talk to me and I try to understand.”

Founding (1749–1800)

The history of European colonization in North America cannot be separated from the European wars that saw territories taken and retaken in battle and traded as bargaining chips in treaties. England and France engaged in conflict in Europe and their various colonies throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Port-Royal changed hands several times; it was finally conquered in 1710 by the English and renamed Annapolis Royal, removing the last French foothold in continental Acadia.

In 1748, further north, the British returned the Fortress of Louisbourg to the French as part of the conditions of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which ended the War of the Austrian Succession. It was not a popular move with the New England colonists who had captured the fort in 1745 and viewed Louisbourg as a threat to trade and, in particular, as a safe harbour for marauding privateers. These concerns were shared by the authorities in London, and a decision was made there to create a counterweight to the French presence on the island of Île Royale (now Cape Breton Island). The British capital, Annapolis Royal, while fortified, did not possess a harbour of sufficient size or depth to become the home of a large fleet, should that be deemed necessary. K’jipuktuk (or, as it had come to be known by the French and British, Chebucto), on the Atlantic side of the Nova Scotia peninsula, did.

The first few years of life in the colony were difficult, and most inhabitants were focused simply on survival. Nonetheless, several early colonists made the time for more cultural pursuits. One of the original settlers was Moses Harris (1730–1787), who drew the first plan of the new colony. Plan of the New Town of Halifax, a map based on his drawing, was subsequently published in London’s Gentleman’s Magazine in October 1749. In 1750, Harris published another map of the town in Gentleman’s Magazine. This map has come to be referred to as the “Porcupine Map,” for its fanciful depiction of the North American mammal. The map also includes insects (a beetle and two butterflies), as well as the coats of arms of various prominent Halifax families. Harris, whose uncle and namesake was a British natural scientist, was following a family tradition in his choice of decoration.

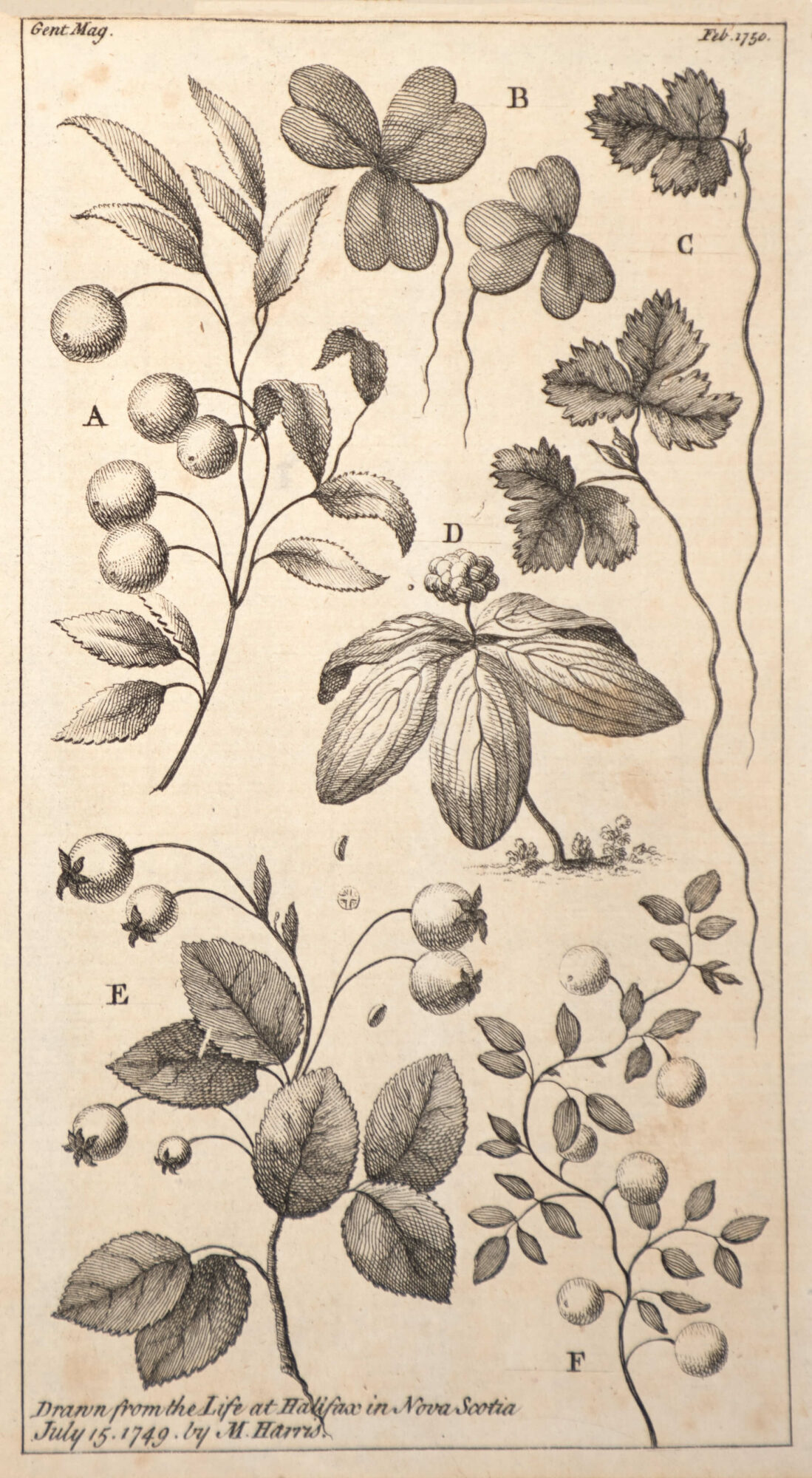

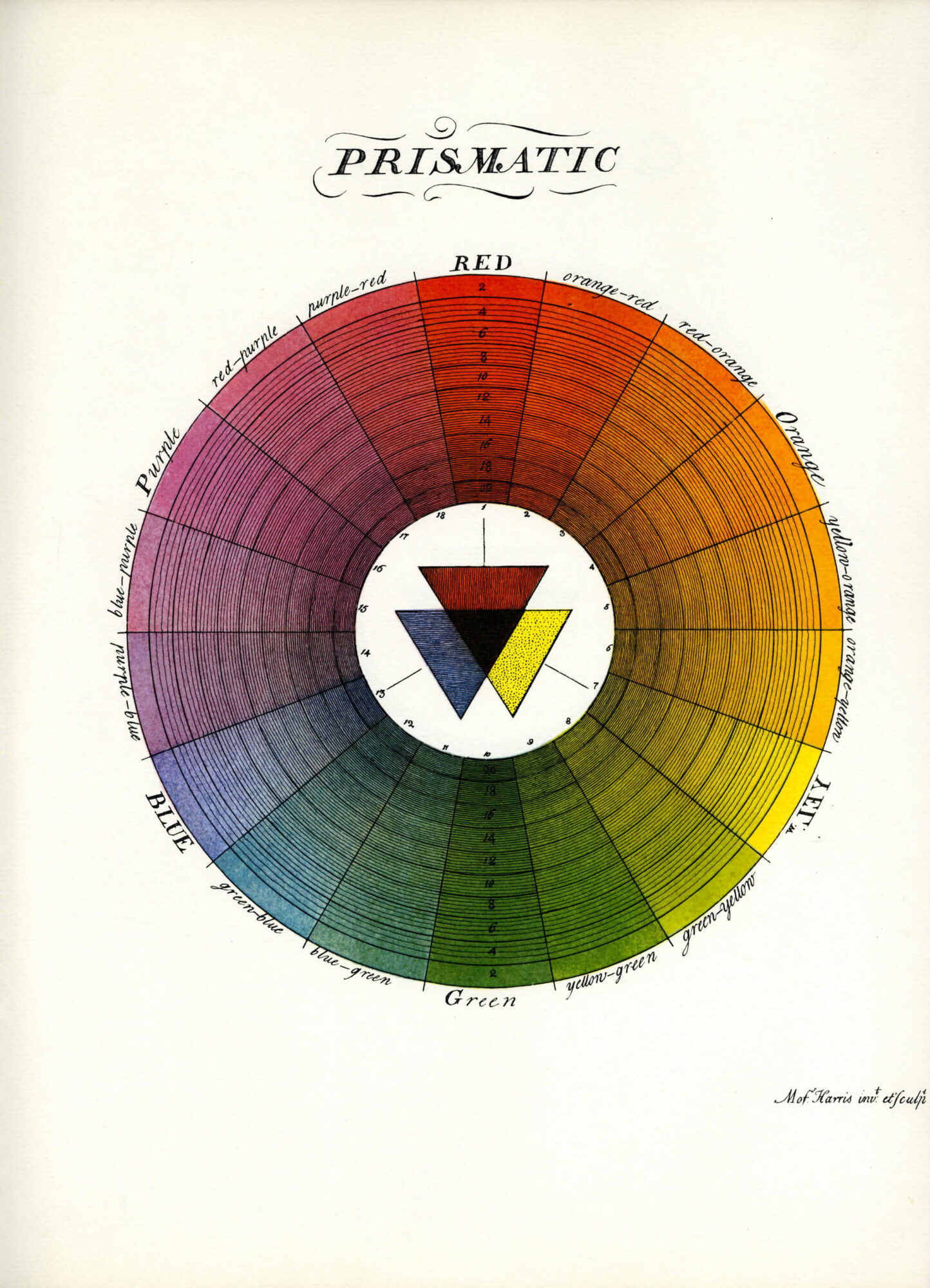

In addition to printing Harris’s two town plans in its pages, the Gentleman’s Magazine in London published an image of six Nova Scotia plants, which were labelled “Drawn from the Life at Halifax in Nova Scotia, July 15, 1749, by M. Harris.” Harris was just eighteen when he came to Halifax, and a budding natural historian. In offering his views he was fulfilling a public desire for information about the new British colonies, as “educated people throughout the Western word were keenly interested in natural history as well as in learning everything possible about the flora and fauna of the New World.” In what would presage the pattern of so many of the artists who made an impact on Halifax, Harris did not remain in the city, and he was back in England by 1752, where he pursued a successful career as an entomologist, engraver, and colour theorist. In 1766 he published The Aurelian: or, natural history of English insects, for which he also provided illustrations, and he later published The Natural System of Colours (c.1769–76), a book on colour theory that was much praised in its time.

While Harris was the first European artist to depict Halifax, the most important was Richard Short (active 1748–1777), the purser of ships including the HMS Prince of Orange. Short, like almost every other artist in the colony, had a day job: he visited Halifax in 1759 as part of General Wolfe’s fleet bound to lay siege to the French fortress city of Quebec. While in Halifax he produced six sketches of the town, and after the British siege of Quebec City he made twelve sketches of that city. The Halifax sketches were first transformed into paintings in England in 1761 and 1762 by Dominic Serres (1719–1793), an English painter who was later appointed the official Marine Painter to George III. Those paintings were the basis for engravings that were published in 1764. Four views of Halifax by Serres are in the collection of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in Halifax.

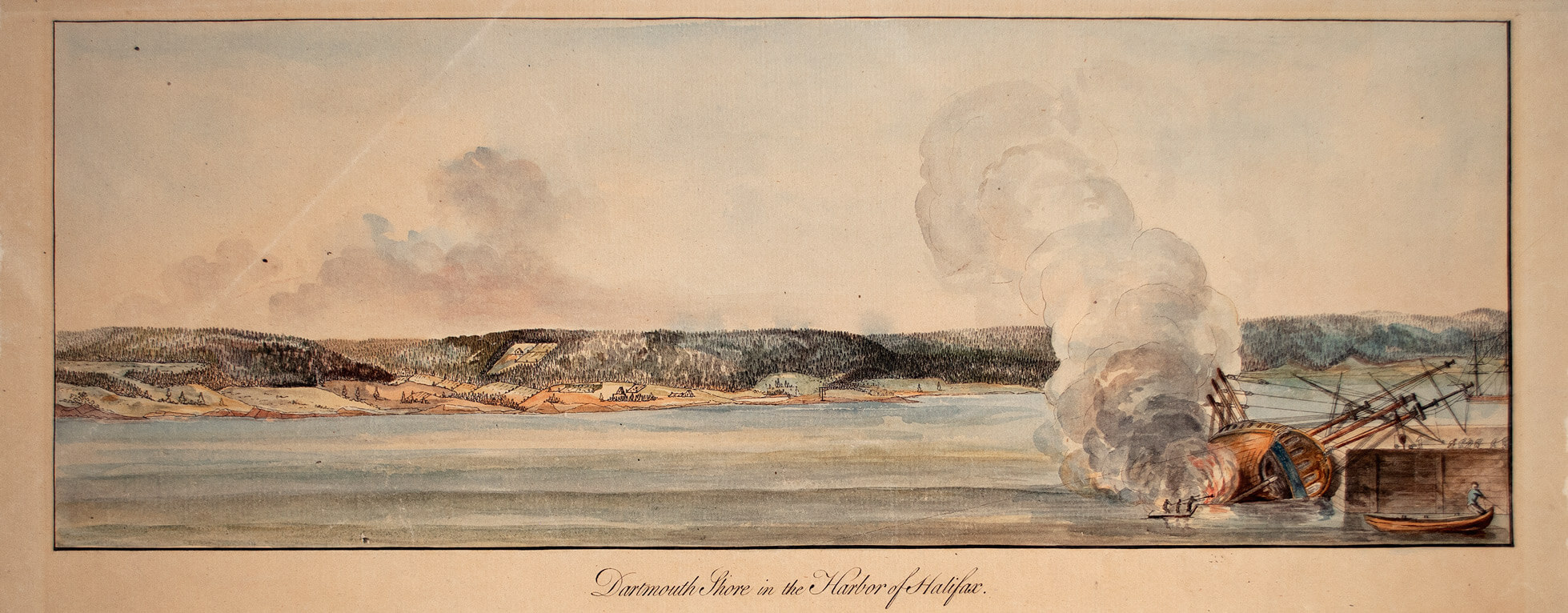

For the remainder of the eighteenth century, most of the views of Halifax that have survived were created by amateurs, most often British military officers trained in topographic illustration and surveying. Among these were Joseph Frederick Wallet DesBarres (1721–1824), who was active in Nova Scotia from 1758 and authored the Atlantic Neptune, published in 1777. Its four volumes included the first coastal survey of Nova Scotia, liberally larded with charts, plans, and engravings of his watercolours and sketches. Lieutenant Colonel Edward Hicks, another British military topographer, was stationed in Halifax from 1778 to 1782, during which time he produced several views of the settlement and its environs. Four aquatints were published on his return to England around 1782. One outlier to the views of the topographers is the popular image Micmac Encampment at Water’s Edge, which was probably first painted by Hibbert Newton Binney (1766–1842), a Collector of Customs and Excise, in about 1790. Numerous versions of this scene of a Mi’kmaw camp on the Dartmouth shore of the harbour exist, including a 1783 copy signed just “J.C.,” tentatively identified by art historian and curator Dianne O’Neill (b.1944) as John Cunningham, a colleague of the Nova Scotia statesman Richard Bulkeley (1717–1800) and likely a member of the Halifax Chess, Pencil and Brush Club.

Prominent citizens turned to New England for the services of professional artists, including Jonathan Belcher (1710–1776), the first chief justice of Nova Scotia and its lieutenant governor from 1760 to 1763, who commissioned his portrait from the American painter John Singleton Copley (1738–1815). So too did Michael Francklin (1733–1782), the lieutenant governor of the province from 1766 to 1772. Copley’s portraits of Francklin and his wife, Susannah, are in the collection of the Nova Scotia Museum.

In those early decades of colonial life, Halifax’s place as a locus of arrivals, migrations, and military manoeuvrings was reflected in the subjects of images produced and collected: ships and newly settled territories, as well as British-born leaders and the peoples they helped displace.

Halifax expanded greatly in the latter part of the eighteenth century, due in large part to its role as a major port for the British fleet during the American Revolution. As the only British colony not in rebellion, Nova Scotia provided a secure supply centre for British forces and a major point of connection with Europe. Later, with the American victory, Halifax became the largest British harbour in continental North America. Trade between Europe, the West Indies, and even the new Southern republic flourished. Prince Edward, later the Duke of Kent and Strathearn (1767–1820), arrived in Halifax in 1794, sparking a period in which, “society reached a peak of brilliance in Halifax and further improvements over the next six years made the whole town shine.”

The Tumultuous Nineteenth Century

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn (1767–1820), left Halifax in 1800, taking with him his enthusiasm for building and much of the social cachet that had surrounded what was, in effect, a royal court. The city experienced a period of depression, which lasted for almost a decade until the new tensions of the Napoleonic wars brought a further influx of British military and trade activity. Born in war, Halifax’s fortunes rose and fell with the geopolitical situation of the day. What was good for the fleet was invariably good for Halifax. The city’s continued expansion through much of the nineteenth century was directly tied to the economies of war: against France, against the United States, and in reaction to the American Civil War, when Halifax became a hub for the import and export of goods that once would have travelled through the blockaded Southern ports.

The arts were as susceptible to the ups and downs of the economy as any other sector, and the nineteenth century saw a cycle of cultural boom and bust that would continue to mark the art history of Halifax until the present day. Artists would find success during boom times and would seek greener pastures in the inevitable downturns.

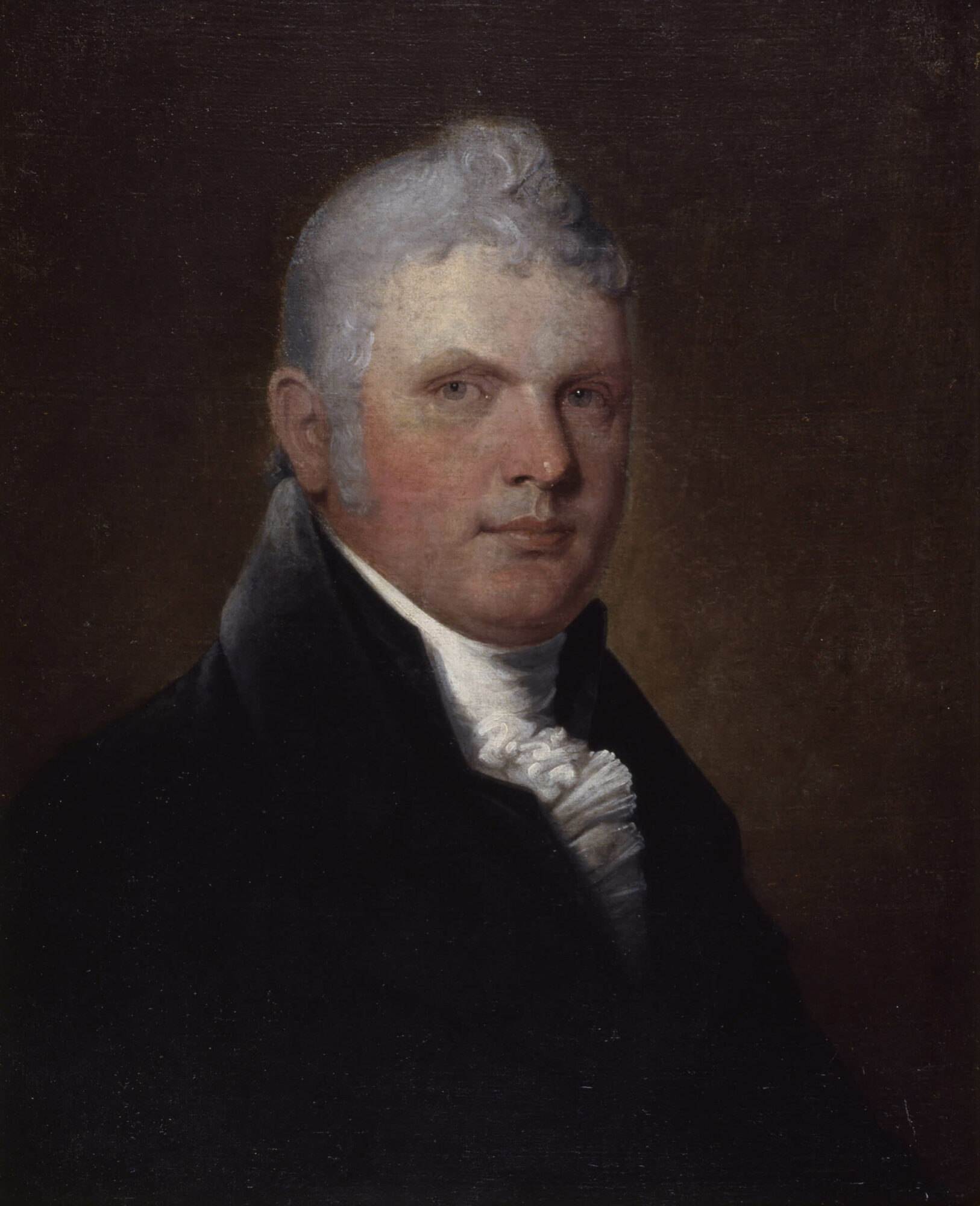

Halifax’s first resident professional artist was drawn to the city by the unrest brewing in the United States in the latter part of the first decade of the nineteenth century. Tensions between England and the United States, which would eventually lead to war in 1812, prompted Robert Field (c.1769–1819), an Englishman who as an itinerant portrait painter had worked for Thomas Jefferson and George and Martha Washington amidst an impressive clientele, to move to Halifax, where his nationality was less of a professional drawback. While his friends in the United States were British, his patrons were increasingly in favour of war with Britain. Field, who had studied at the Royal Academy in London, lived in Halifax from 1808 until 1816, executing numerous portrait commissions. He was apparently well-connected socially, as during his first year in Halifax he painted portraits of the then-current lieutenant governor and his immediate predecessor. Both men were members of the exclusive Rockingham Club, and Field executed numerous portraits of the club’s members over his eight years in Halifax. The end of the Napoleonic Wars prompted another economic downturn in Halifax, and in 1816 Field moved on to Jamaica, where he died of yellow fever.

Portraits were in great demand among nineteenth-century government, church, and military officials, and several other itinerant artists visited Halifax in the first decades of the nineteenth century, seeking portrait commissions and often offering art instruction. Perhaps the best-known of these was John Poad Drake (1794–1883), who left a life-size portrait of Chief Justice Blowers (1742–1842) and at least two depictions of Halifax Harbour (one now in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada, and one, Shipping at Low Tide, Halifax, c.1820, at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia).

Watercolour landscapes and miniature portraits were popular in early Halifax. Among the pieces that have survived are works by Joseph Comingo (1784–1821), a painter who is credited by some scholars as being Canada’s first native-born professional artist. Comingo’s time in Halifax overlapped with Robert Field’s, and he worked throughout the Maritimes before settling in the Bahamas. There has been some speculation by later historians that he had been Field’s student.

Topographic art, particularly works documenting the burgeoning colonies, was another nineteenth-century passion. The genre arrived along with the architect and painter John Elliott Woolford (1778–1866), who came to Halifax in 1816 as part of the retinue of the new lieutenant governor, Lord Dalhousie (1770–1838). Woolford’s artistic abilities had first caught the attention of the earl years prior: at nineteen, Woolford had entered the army and served as a soldier under Dalhousie’s command in Malta. When the regiment was mustered for a campaign in Egypt in 1800, Woolford was no longer a foot soldier, but was instead tasked by Dalhousie to visually document the expedition.

In 1816 Dalhousie employed Woolford as a draftsman; for the remainder of Dalhousie’s military and political career Woolford would work for him as an artist chronicling his travels. Upon his arrival in Canada in 1816, Woolford began creating a series of landscape views of Halifax and of locations further afield in Nova Scotia. In 1819 he published four aquatints of Halifax—two of Province House (the meeting place of the Nova Scotia House of Assembly) and two of Government House (the residence of the lieutenant governor).

One of the best-regarded topographic artists active in Halifax in the early nineteenth century was the Irish-born William Eagar (c.1796–1839), who was also instrumental in introducing lithography to Halifax. Eagar worked around Atlantic Canada, teaching painting as well as introducing commercial lithography to the region. (Lithography would eventually have immense importance to the art history of Halifax with the creation of the NSCAD Lithography Workshop, which ran from 1969 to 1976, and had a contemporary reintroduction from 2017.)

Most of the artists in early colonial Halifax, a fortress town, had other professions: surveyor, maritime officer, soldier. Indeed, the British garrison continued to provide artists throughout the nineteenth century, including Robert Petley (1812–1869). Petley was stationed in Halifax from 1832 to 1836. In 1837 he published a series of lithographs in London, Sketches of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

While the elite classes were interested in portraits, there was rarely enough demand for these to fully sustain artistic careers. One of the more important artists in this time, William Valentine (1798–1849), was a professional painter, albeit one who did not always work in the fine arts. He also painted signs and houses, running a business that offered painting and decorating services. Valentine arrived in Halifax from his native England in 1818. Self-taught, he moved in different social circles than had Robert Field, and his clientele were drawn from the middle, rather than the ruling, classes. By 1821 he had opened a drawing school, and in 1831 he was one of the founders of the Halifax Mechanics’ Institute, which offered lectures and technical classes on a broad array of subjects, including the arts. In 1842 Valentine introduced the daguerreotype process to Halifax, opening the first photographic studio in Nova Scotia.

Another educator worth mention is W.H. Jones (active at Dalhousie College 1829–1830), a short-term resident of the city from Boston who taught painting at Dalhousie College (now Dalhousie University). Jones organized Halifax’s (and British North America’s) first art exhibition at Dalhousie College, which ran from May 10 to 29, 1830. The majority of the works on view were by his students, but he also included works borrowed from local collections. Jones’s brief period teaching at Dalhousie College from 1829 to 1830 was most noteworthy because he provided art instruction to Maria Morris (later Miller) (1810–1875), who published four volumes of hand-coloured lithographs of Nova Scotia flora and was Halifax’s first woman professional artist.

Halifax’s importance as a trading port increased throughout the nineteenth century, and ship portraits (images of sailing vessels which expressed pride of ownership and also served as records for insurance purposes) became an important part of the artistic activity of the city. John O’Brien (1831–1891) was born in Saint John, New Brunswick, and raised in Halifax. He was working as a sign painter and a self-taught ship portrait painter when his artistic talent was recognized by a group of Halifax merchants who funded his art studies in Europe. Most painters of ship portraits lacked formal training; O’Brien’s academic training and relative sophistication made his work highly prized. He was also credited as being Halifax’s first native-born professional artist (forgetting Maria Morris Miller, who did not get her due until much later).

While Confederation in 1867 eventually brought political stability to Nova Scotia, it also narrowed Halifax’s role as a major part of the British defences. The garrison, long the social and cultural engine of the city, decreased in size, along with the British naval presence. As a result, the market for art in Halifax declined after Confederation, and despite the individual prominence of certain artists, the arts in Halifax were not flourishing. “Painters of ability failed to build on these beginnings and a real ‘scene’ for painting never did develop in Halifax,” one historian wrote.

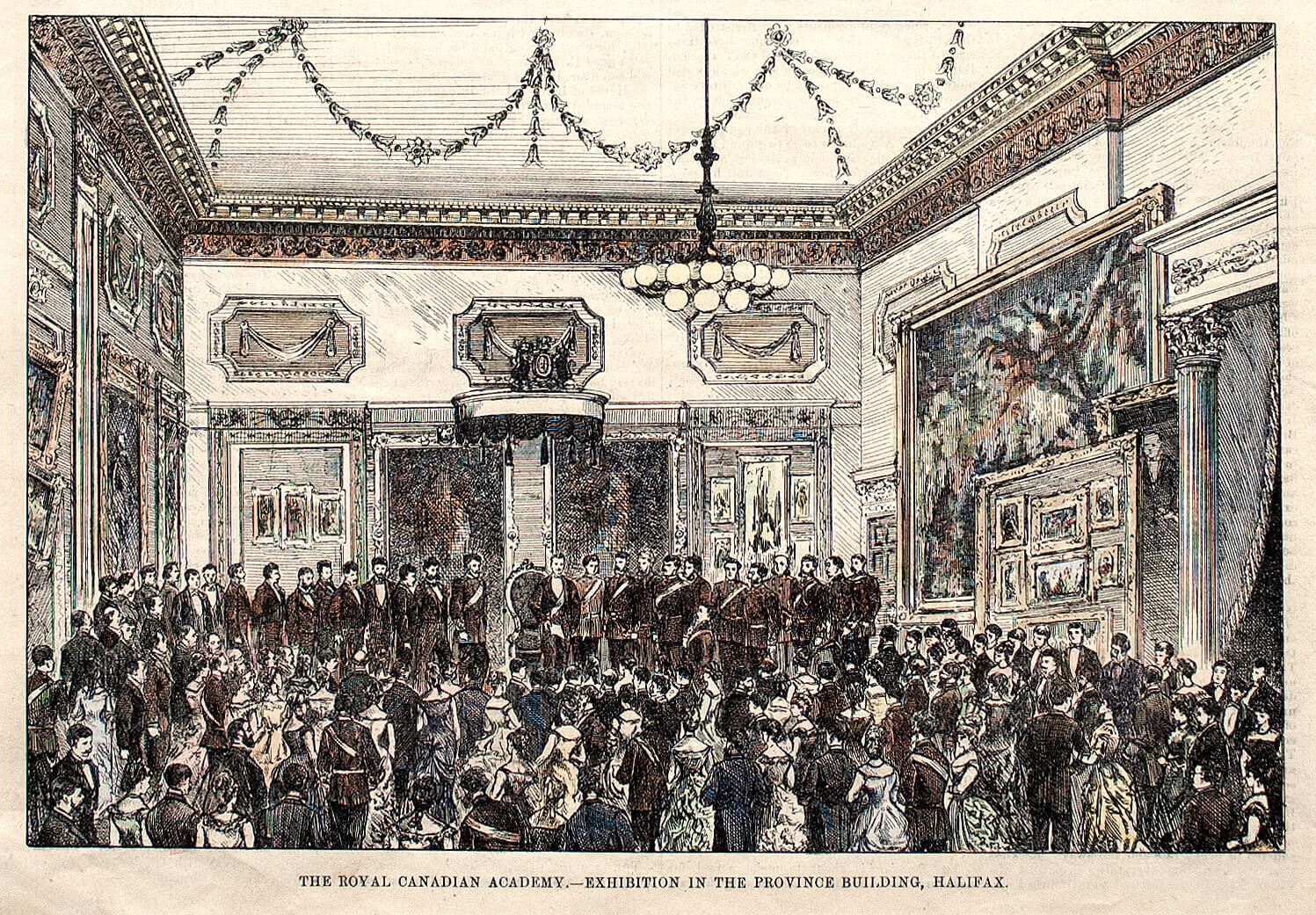

It was not until the 1880s that conditions for such a “scene” seemed to be in place, though Halifax remained a difficult place for the arts and for artists. In 1881, the second exhibition of the fledgling Royal Canadian Academy of Arts was held in Halifax. The exhibition was a popular success, but so few paintings sold that the Academy did not hold its annual exhibition outside of Toronto, Ottawa, or Montreal again. At the show’s opening the governor general, the Marquis of Lorne (1845–1914), called for the creation of an art school in Halifax. Despite having had occasional instruction available from at least 1809, when an artist named John Thomson offered drawing classes from his studio, Halifax had never had an established institution for art instruction. A group of prominent Haligonians took up the challenge, including Anna Leonowens (1831–1915), former governess to the King of Siam’s children and a Victorian celebrity due to her travel writing (she was made famous again in the twentieth century by the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical The King and I).

The Victoria School of Art and Design (VSAD) was founded by Leonowens in 1887, with English landscape painter George Harvey (1846–1910) as its first headmaster (the job title was changed to principal in 1895). The school struggled though the remainder of the nineteenth century, rarely having more than a few hundred part-time students, with five different leaders before the turn of the century. Some relative stability was introduced in 1898 with the appointment as principal of the American artist Henry M. Rosenberg (1858–1947), who remained in the position until 1910.

The Arrival of Modernism (1901–1967)

The first decades of the new century were noteworthy in the arts for the growth of the Victoria School of Art and Design (VSAD). Its principal in that first decade, Henry M. Rosenberg (1858–1947), had known James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) in Europe and Ernest Lawson (1873–1939) in New York. Whistler was the most famous artist of his era, while Lawson, a native of Halifax, was well known as a founder of American Impressionism and a member of The Eight (a group of artists in New York who advocated for a distinct style of American painting, much as Canada’s Group of Seven began to do for Canadian art twelve years later). Rosenberg brought the prevailing international styles of Tonalism and Impressionism to Halifax, where he remained an influential artist after his retirement from teaching in 1910. Rosenberg was also part of a group of Haligonians who founded the Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts in 1908, which aspired to build an art museum in Nova Scotia’s capital.

Halifax was a major port for sending troops and arms to Europe during the First World War, with massive convoys gathering in the Bedford Basin before braving the North Atlantic and the German U-boats. The bustling wartime city was devastated in December 1917 by the Halifax Explosion, caused by the collision in the harbour of a munitions ship and a freighter. The explosion, which until the first detonation of an atomic bomb was the largest humanmade explosion in history, killed almost 2,000 Haligonians, and left over 9,000 blinded, burned, and otherwise injured.

-

Looking north toward Pier 8 from Hillis foundry after great explosion, Halifax, December 6, 1917

Photograph by W.G. MacLaughlan

Nova Scotia Archives, Halifax -

A.Y. Jackson, The Old Gun, Halifax, 1919

Oil on canvas, 54.2 x 65.4 cm

Art Gallery of Hamilton -

Harold Gilman, Halifax Harbour, 1918

Oil on canvas, 198 x 335.8 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa -

Arthur Lismer, Olympic with Returned Soldiers, 1919

Oil on canvas, 123 x 163.3 cm

Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, Canadian War Museum, Ottawa -

Arthur Lismer, Troopship Leaving Halifax, 1918

Lithograph on paper, 30.7 x 40.4 cm

Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax

War artists such as A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) and Harold Gilman (1876–1919) made important paintings of Halifax during this period. Gilman’s Halifax Harbour, 1918, depicts the city after the explosion, a seeming calm that “evokes a sense of tranquil order that offsets the drastic aberration represented by the explosion and the war more broadly.”

But the official war artist most important to Halifax’s history was surely Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), the future founding member of the Group of Seven. Lismer was hired in 1916 to become the principal of VSAD, and he lived in Halifax until 1919. During the First World War Lismer recorded the military activity around Halifax and its harbour. He created several paintings of camouflaged ships, such as Convoy in Bedford Basin, 1919, and Olympic with Returned Soldiers, 1919—both now in the collection of the Canadian War Museum—now in the Canadian War Museum collection—as well as a series of lithographs depicting the batteries and gun installations around the harbour. Under his tenure both the art school and the art museum grew, although he met resistance in his efforts to modernize the school. “Anything in the way of innovation is met with exasperating apathy,” he complained of Halifax’s conservative community.

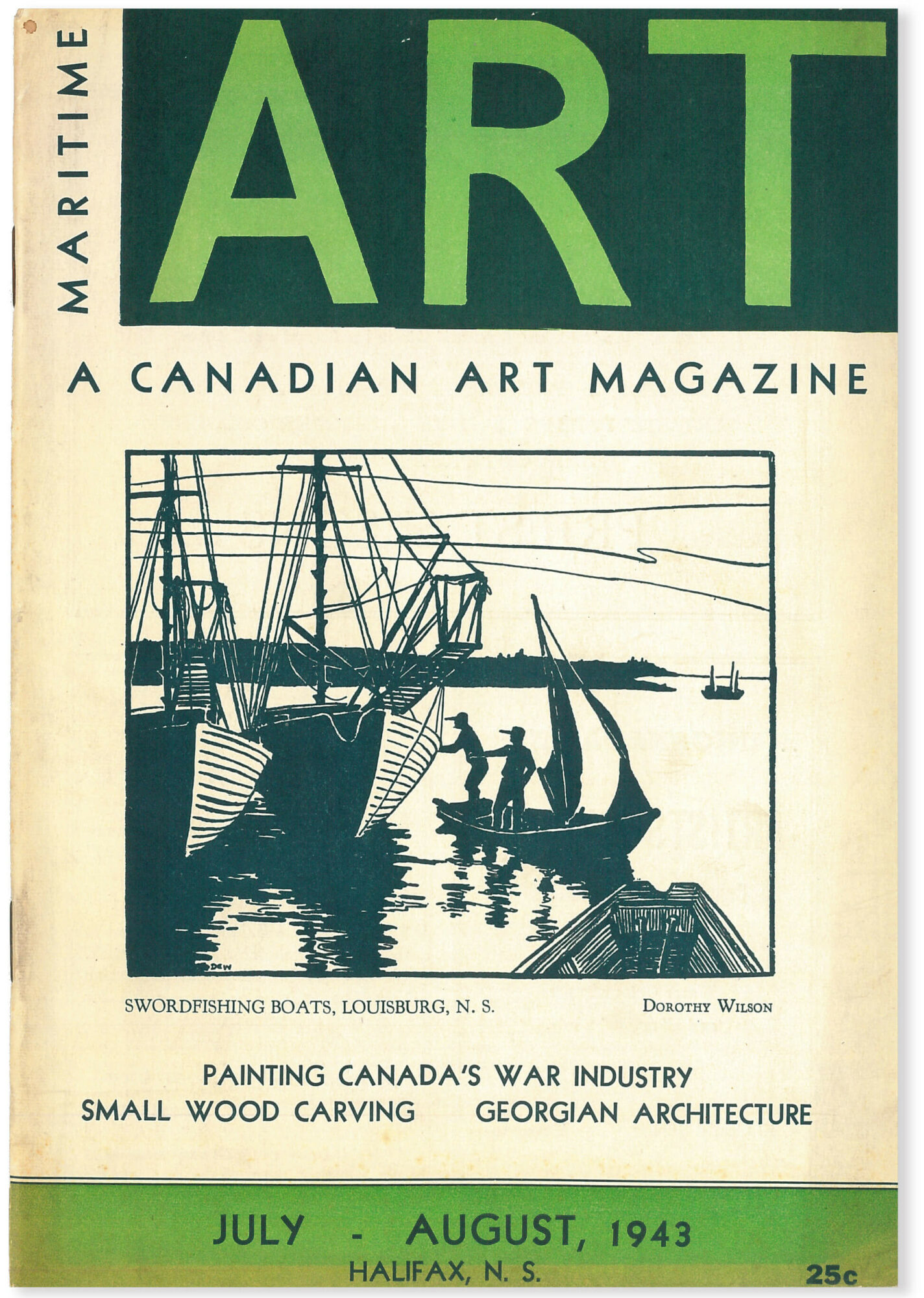

The years after the war saw a surge in artistic activity. In 1922 the Nova Scotia Society of Artists (NSSA) was founded in Halifax. Its first exhibition was at VSAD, thanks to the organizational energies of Lismer’s successor at VSAD, British painter Elizabeth Styring Nutt (1870–1946) (while not a founding member, Nutt became president of the NSSA in 1929). The NSSA organized art classes and regular exhibitions for more than five decades. The Victoria School of Art and Design was renamed the Nova Scotia College of Art (NSCA) in 1925 and continued to expand under the leadership of Nutt. In 1935 a collective of galleries and other exhibition venues formed the Maritime Art Association, which concentrated on organizing and borrowing art exhibitions that toured throughout the region. It also began publishing Canada’s first dedicated arts journal, Maritime Art (later Canadian Art), which launched in 1940 under the editorship of art history professor and Acadia University gallery curator Walter Abell (1897–1956).

Not long after, Halifax was once again an important staging point for the armies and the shipping of the Second World War, with official war artists depicting the activities both on the home front and in the Battle of the Atlantic. Post-war, the arts in Halifax were given a boost by the creation of the Dalhousie Art Gallery in 1953, the first permanent art gallery in the city.

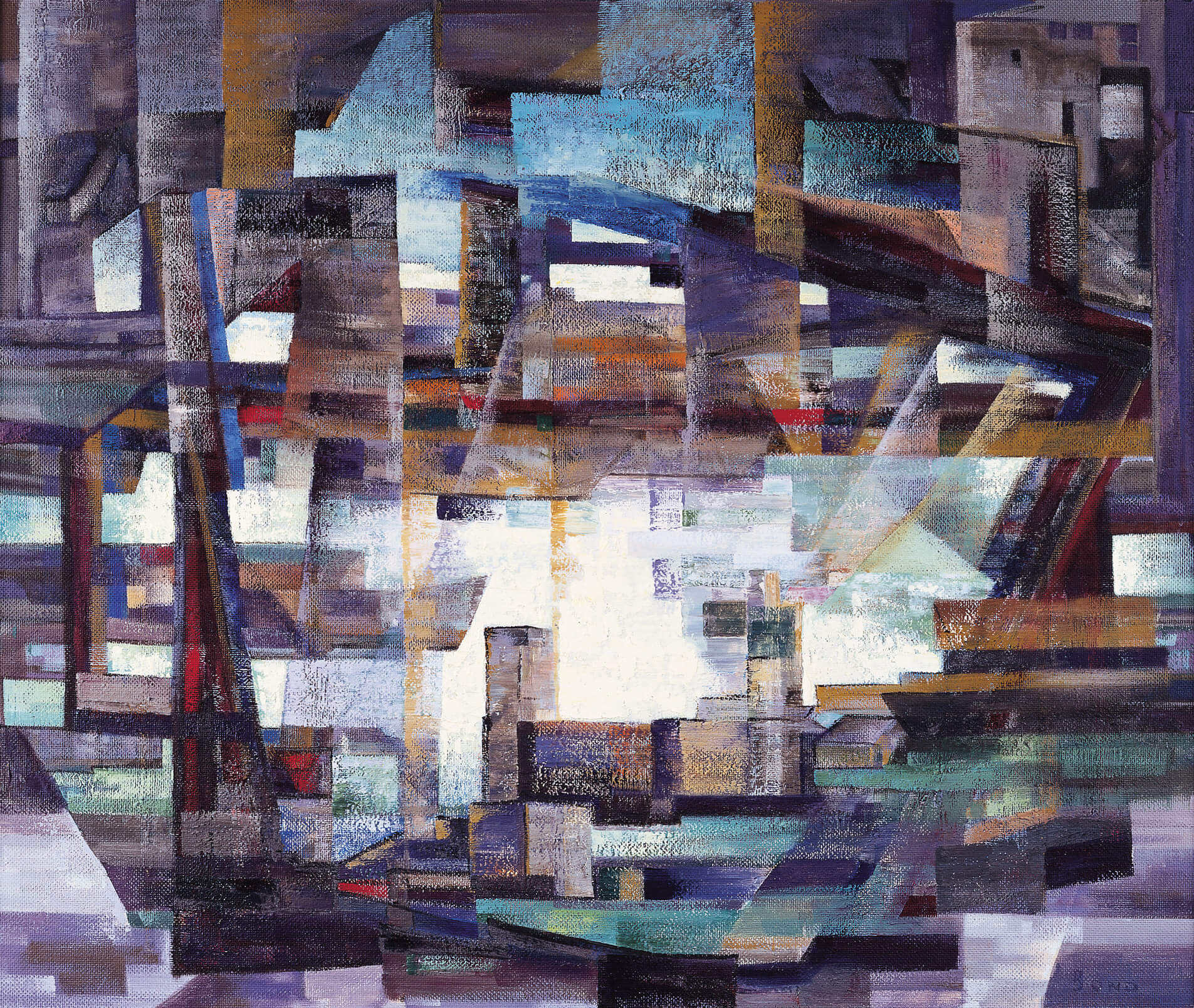

The predominance of abstraction in Canadian painting, as evidenced by the Automatistes in Montreal and Painters Eleven in Toronto, among others, was bringing much change to the arts in Canada, though less so in Halifax, where the arts remained relatively conservative and focused on realism and Post-Impressionist landscape painting. This was driven as much by the tastes of patrons for art as it was by the relatively conservative atmosphere at the art college that resisted any attempts to introduce more contemporary ideas into the curriculum.

The annual exhibitions of the Nova Scotia Society of Artists were replete with views of Peggy’s Cove and other seascapes, of Point Pleasant Park, and of the shipping in the harbour. Some artists, such as Marion Bond (1903–1965), LeRoy Zwicker (1906–1987), and Leonard Brooks (1911–2011), experimented with abstraction. Ruth Salter Wainwright (1902–1984) and Aileen Meagher (1910–1987) went so far as to take classes at the famous summer school run by Hans Hofmann (1880–1966) in Provincetown, Massachusetts. Carol Hoorn Fraser (1930–1991) experimented with Surrealist themes in her figurative paintings, and from the late 1950s sculptor Sara Jackson (1924–2004) was making bronze works that in their expressive Surrealism would not have looked out of place in London or Paris. But for the most part, while the international art world was roiled by Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop art, and Minimalism, most artists in Halifax seemed content with the status quo.

The conservatism of the NSCA, fostered under Elizabeth Styring Nutt’s long tenure (from 1919 to 1943), continued under Nutt’s successor, Donald Cameron (D.C.) Mackay (1906–1979). Arthur Lismer, who was consulted about Nutt’s replacement, was well aware of his old school’s limitations, and was lobbying for a successor to Nutt. “The day of the studio practices of fifty years ago in England is pretty near over and the standards of design, painting and achievement generally have been advanced and changed,” he wrote to one NSCA board member, in a letter recommending Frederick Varley (1881–1969) as the new principal. Mackay did not bring the changes Lismer recommended. Instead, “the overall picture of mid-1960s NSCA was one of artistic torpor and depressed staff and student morale.”

The art school was not alone in its conservatism. The Maritime Arts Association and the Nova Scotia Society of Artists were also criticized for contributing to what Stuart Smith, the director of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, called in 1967 “a reactionary and restrictive influence on painting in all three provinces.” Smith blamed a coterie of “Sunday painters” for this influence, suggesting that “financial stagnation” may have been partly to blame.

As artist and art dealer LeRoy Zwicker wrote in Canadian Art in 1945, audiences in Halifax, “this conservative old city,” preferred regional subjects: “The regional dealer must understand his region. It is natural that the conservative characteristic would find an echo in what is known as ‘sound’ painting.” Far from implying any sort of experimentation, Zwicker meant that the community preferred orthodox painting, finding it more “sound” than the contemporary trends. The market, such as it was, simply would not support more innovative practices. While the market never would catch up, innovation, in the form of a new art school president, was poised to arrive later that year.

Postmodernism (1967–present)

In 1967 Garry Neill Kennedy (1935–2021) was appointed the first president of the Nova Scotia College of Art, which in 1969 was renamed the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD). In his first decade at the art college he oversaw two major expansions: first the addition to the college’s campus on Coburg Road, and then, in the late 1970s, its move to a block of historic buildings on the Halifax waterfront. Kennedy also refocused the school, firing or retiring most of the faculty that had been in place and hiring a new, mostly American, group of artists who were products of university art programs and interested in innovative approaches to visual art. New faculty members such as Gerald Ferguson (1937–2009), David Askevold (1940–2008), Walter Ostrom (b.1944), Eric Fischl (b.1948), Martha Wilson (b.1947), Benjamin H.D. Buchloh (b.1941), and Kasper König (b.1943) radically changed Halifax’s conservative art school.

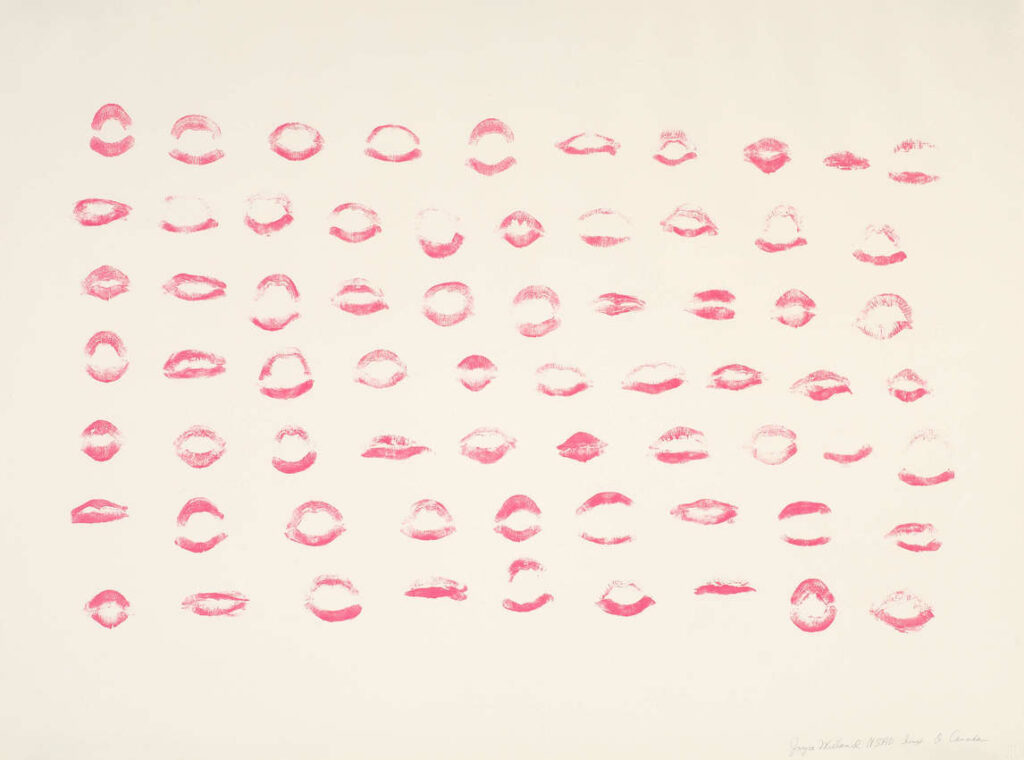

Realism and Post-Impressionism were abandoned in favour of Conceptual art approaches. Easels were discarded, and pottery wheels were, albeit briefly, banished from the ceramics studio. Video, performance, land art, and installation all became part of the curriculum, and NSCAD’s Visiting Artists Program brought contemporary artists from across the world to Halifax. The school established two exhibition spaces, the Mezzanine Gallery and the Anna Leonowens Gallery, which rapidly became the most innovative exhibition venues in Atlantic Canada, featuring work by students and faculty as well as by visiting artists such as Gerhard Richter (b.1932), Dan Graham (1942–2022), John Baldessari (1931–2020), Lawrence Weiner (1942–2021), Jackie Winsor (b.1941), Joyce Wieland (1930–1998), and Michael Snow (1928–2023). The NSCAD Lithography Workshop (1969–76) and the NSCAD Press were active throughout the 1970s and produced a body of work unparalleled in Canadian art history.

But it wasn’t just the art school that was sparking fundamental change in the arts in Halifax. Two Halifax universities, Mount Saint Vincent University and Saint Mary’s University, founded art galleries in 1971. The Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts had been operating the Centennial Art Gallery in a powder magazine on Citadel Hill since 1967, and in 1975 it moved into the former premises of NSCAD on Coburg Road. Through an act of legislature its collection was granted later that year to the newly incorporated Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (AGNS). One of the AGNS’s first major exhibitions was Folk Art of Nova Scotia, a nationally touring exhibition that introduced Nova Scotia folk art to Canadian audiences. Folk art would remain a major focus of the AGNS, culminating in a series of major exhibitions in the 1980s and 1990s.

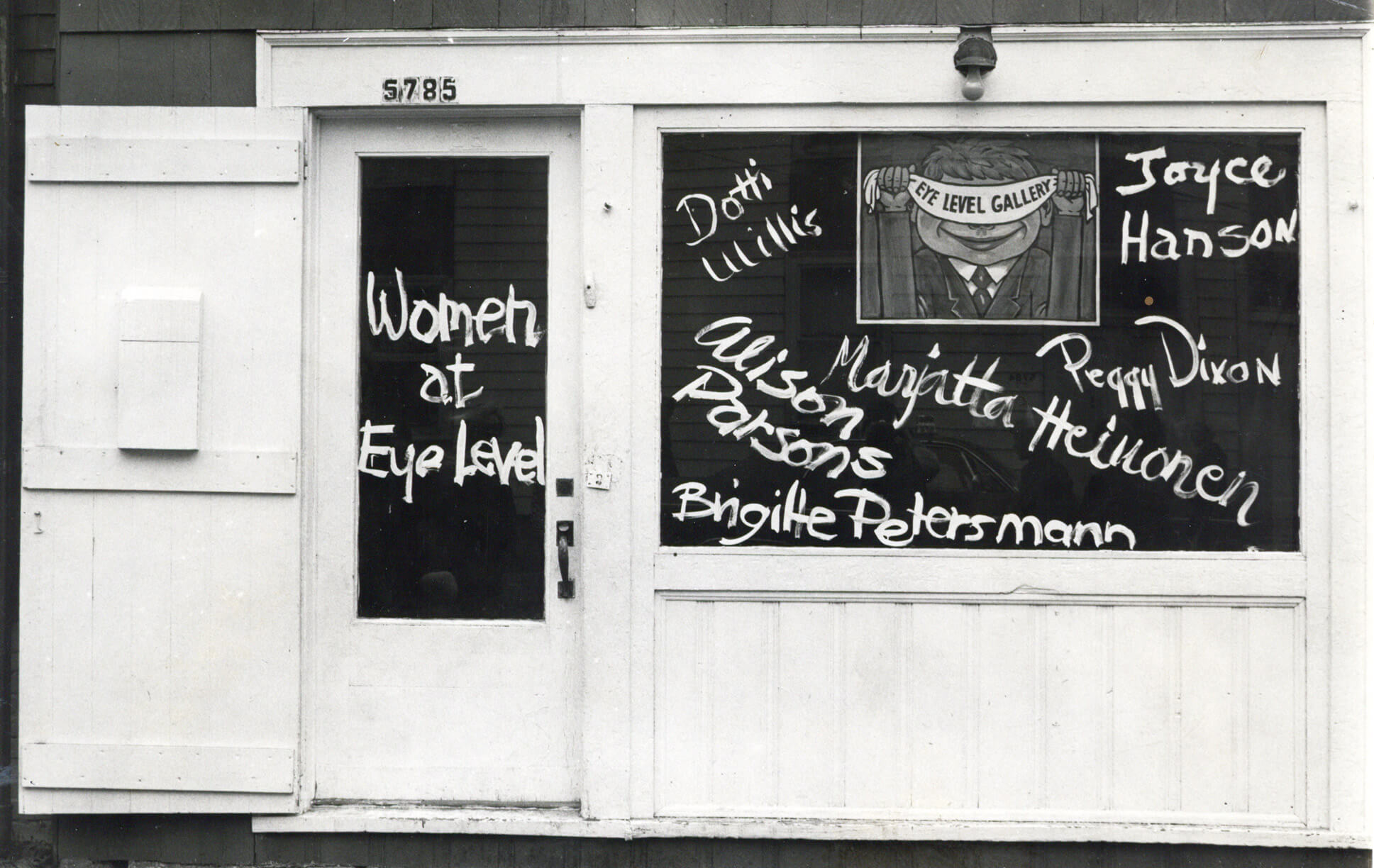

In 1972 a group of women artists founded Inventions Gallery, a short-lived artist-run space that became Eye Level Gallery Society (now Eyelevel) in 1974. That same year the Atlantic Filmmakers Cooperative was established. The seventeen founding members were inspired in part by the frequent visits to Halifax of Robert Frank (1924–2019), who had a home in Cape Breton. Frank sold the co-op their first film camera, the same one he had used to shoot Cocksucker Blues, his infamous documentary about the Rolling Stones. Both artist-run centres benefited from new funds available from the Canada Council for the Arts. The Centre for Art Tapes, an exhibition and production facility concentrating on video and sound art, was founded in 1979. The AGNS moved downtown from the Dalhousie University campus in 1988 into a renovated historic building a few blocks away from NSCAD. Its inaugural exhibition was a history of the art school, Eighty/Twenty: 100 Years of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design.

Despite the number of art galleries in Halifax, artists continued to create their own exhibition venues. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s there were numerous artist-driven initiatives aimed at expanding the exhibition opportunities for emerging contemporary artists. The Ecphore Exhibition Society was founded in 1986 and mounted three annual exhibitions in empty buildings in Halifax’s downtown. Submissions were open to all artists and the exhibitions ran over a weekend each fall. The lawn of the Technical University of Nova Scotia became the venue for several outdoor sculpture shows in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Following this series of shows were two significant exhibitions organized by young sculptors: the empty Pier 21 site on the Halifax waterfront was the venue for The Shed Show in 1993, and a mostly vacant shopping centre became the site for Sculpture Expo ’94: The Mall Show in 1994, an exhibition featuring nineteen artists. In the early 1900s a short-lived gallery opened in Halifax, a co-op space for contemporary art called OO Gallery. The Khyber Centre for the Arts, a new artist-run centre, was opened in 1995 in a run-down historic building on Barrington Street.

Artist-run spaces and events and the university galleries were the major venues for contemporary art in Halifax from the 1970s until the turn of the century. Despite the international attention being turned to Halifax, and the exhibitions at the Anna Leonowens Gallery of artists such as Gerhard Richter (b.1932), A.R. Penck (1939–2017), Alice Aycock (b.1946), Lawrence Weiner (1942–2021), Richard Prince (b.1949), and John Baldessari (1931–2020), amidst many other now-famous names, Halifax audiences remained interested in regional landscapes—in conservative, or what LeRoy Zwicker (1906–1987) had pejoratively termed “sound,” painting. No works from these exhibitions were acquired by Nova Scotia collections (public, corporate, or private).

There were very few commercial galleries in Halifax, and most did not exhibit the kind of work considered cutting-edge. Zwicker’s Gallery, the oldest commercial art gallery in the region (opened by Judson A. Zwicker, and later run by his son, LeRoy), was founded in 1886. By the 1980s the gallery was mostly focused on the secondary market. Its contemporary offerings were mostly works of Atlantic Realism. Secord Gallery was founded in 1979 and represents numerous Nova Scotia artists, many representational in style, though they do also feature abstract painters as well as printmakers, photographers, and sculptors. The first commercial gallery that attempted to represent artists who were also being exhibited widely in public galleries was Studio 21 Fine Art, founded in 1983 by artist Ineke Graham (b.1937). With a mix of artists from the region and the rest of Canada, Studio 21 became the most successful commercial gallery in the city, albeit with a relatively conservative stable of artists. (In September 2023, Studio 21 changed ownership and became Katzman Art Projects.) Gallery Page and Strange, which opened in 2005, also focused on contemporary art, but was unable to survive in the difficult Halifax market.

Despite having an active public gallery sector, opportunities for critical attention from magazines and newspapers, and the constant churn of activity around NSCAD, Halifax has never been able to sustain an art market large enough to create a sense of critical mass in the arts. Dependant on teaching, grants, and work in other fields (such as the film industry), art careers in Halifax are tenuous, and many artists move on to other cities.

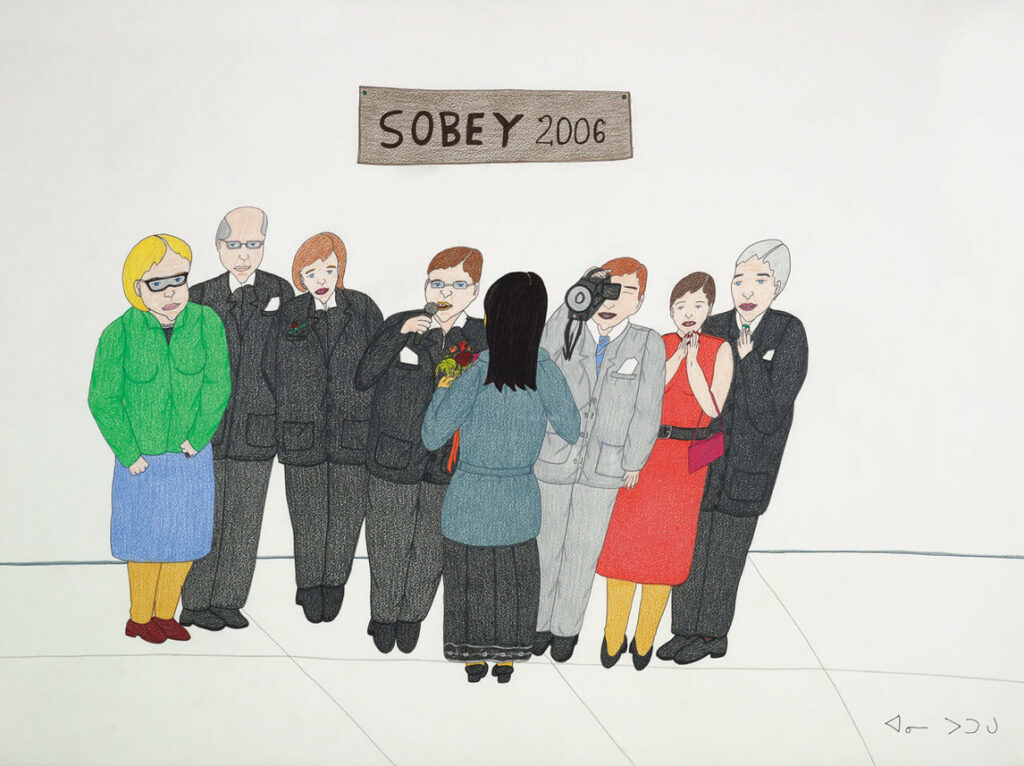

An important step forward was taken in 2001, when the Sobey Art Foundation, through the AGNS, founded the Sobey Art Award. This prize, the largest for the contemporary arts in Canada, was managed by the AGNS until 2015; in 2016 the award was moved to the National Gallery of Canada. Through its annual exhibitions and jury meetings in Nova Scotia, curators from across Canada were brought to Halifax and given the opportunity to see works by artists in the city (whether or not they were in contention for the award), raising the profile of the contemporary arts exponentially. This in turn led to increased visibility, nationally and internationally, for contemporary artists in the city.

Halifax began a series of major developments on the peninsula in the early part of the twenty-first century that created pressure on artists in terms of finding affordable studio space. The days of empty, or even affordable, centrally located spaces were over, and as in other cities across North America, the downtown core, once the hub of contemporary art activity, became too expensive for artists and artist-run centres, forcing their move further and further away from the city centre.

Yet artists continue to make significant change themselves. In 2019, artist Emily Falencki (b.1972) purchased a large former printing facility in the city’s North End and renovated it extensively to create a new art institution. The Blue Building, which opened in 2021, now houses artist studios, production facilities, educational programs, Eyelevel’s office and bookstore, and an artist-led commercial gallery. As the saying has it, a rising tide lifts all boats. The opening of The Blue Building complex fuels optimism that Halifax’s art scene is making its next leap.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements