Halifax has always been a city in transition, a point of arrival and departure, permeable and impermeable at once, one of Canada’s contact points with the rest of the world. Halifax was established as a fortified town, a direct response to the French Fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island; its very reason for being was to defend against perceived enemies. Nonetheless, the city has also witnessed much social and cultural change as it has absorbed (if not always welcomed) influences from around the world.

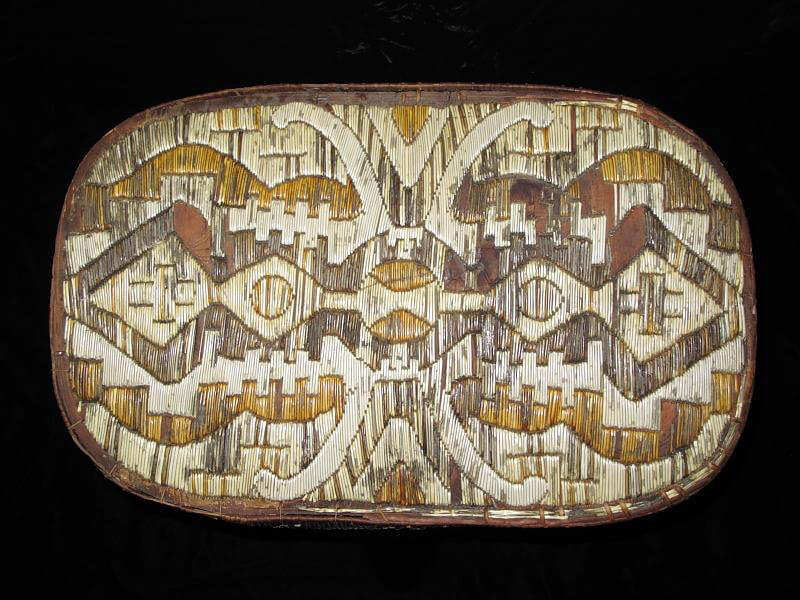

One of Canada’s oldest cities, Halifax has been the site of many important firsts in Canadian history, including the first elected representative assembly and the first newspaper. It was also the home of the first public art exhibition, the first fine art association (the Halifax Chess, Pencil and Brush Club, founded in 1787), and the first degree-granting independent art college. All but the last were achievements that predate Canada itself, reflecting the long history of European settlement around the “great harbour.” And as is true of any colonial city, settlers brought their idea of the arts with them, overlooking or dismissing what was already here. Because, of course, the Mi’kmaq, whose unceded land this city occupies, have their own visual culture, one aspect of which, their petroglyphs, is literally written on the land. Halifax’s art history long predates the city itself.

Kjipuktuk, meaning “the Great Harbour” and transliterated by the British and French as “Chebucto,” is the Mi’kmaw name for Halifax Harbour. Situated on the Atlantic Coast, it is one of the deepest harbours in North America and its strategic advantages were early on recognized by the European colonial powers. The Town of Halifax was founded on the shores of Kjipuktuk in 1749; it was named after the second earl of Halifax, George Montagu Dunk (1716–1771), who was responsible for the mission to establish a fort and city on the site. Its settlement sparked decades-long strife with the Mi’kmaq, who objected to the British presence on, and usurpation of, their territory. The first governor of Halifax, Edward Cornwallis (1713–1776), ordered vicious attacks on the local Mi’kmaw residents that amount to attempts at genocide. Long years of conflict were finally ended, if not resolved, by the Peace and Friendship Treaties signed in 1760 and 1761, which still bind the Crown’s relationship with the Mi’kmaq.

Garrison towns are often conservative; perhaps it is the nature of their origins. Despite a strain of insularity (sculptor and writer Robin Peck [b.1950] has described Halifax as “a place so well-defended that nothing ever happened”), the city’s defensive norms and conventions have been challenged by visitors as diverse as Oscar Wilde, Duke Ellington, and the Rolling Stones. In the visual arts, occasional visitors have often been as influential as—and often more influential than—residents. Joseph Beuys (1921–1986), Gerhard Richter (b.1932), Dan Graham (1942–2022), and John Baldessari (1931–2020), for instance, made only brief stops in this place, but influenced generations of artists.

The city’s art history, too, is a story of a series of arrivals and departures. Arthur Lismer (1885–1969) came for a few years and struggled mightily to change the city’s culture. He succeeded only partially, and the art school he ran reverted to a more conservative path after his experiments, although its core program expanded greatly under Lismer’s successors. Garry Neill Kennedy (1935–2021) took that same art school fifty years later and shook it out of its comfort zone, creating an internationally renowned centre for artistic experimentation. Under his leadership, the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (now NSCAD University) brought in artists and scholars such as Gerald Ferguson (1937–2009), David Askevold (1940–2008), Kasper König (b.1943), Benjamin H.D. Buchloh (b.1941), Lucy Lippard (b.1937), Eric Fischl (b.1948), and many, many more. Some stayed for just days, some for months or a few years. Some stayed for decades. But Kennedy himself eventually left, moving to Vancouver after his retirement from NSCAD and taking up a teaching appointment at the University of British Columbia.

Most of the college’s graduates leave, ensuring that Halifax’s influence on the fine arts in Canada and beyond is as much a function of exporting artists, curators, writers, and educators as it is from activity that happens within the city itself. For those who stay, Halifax can be a tough place to be an artist, with not much of an art market and few opportunities for work except for NSCAD University and the (often struggling) film industry. However, with its four university art galleries, four artist-run organizations, and a public art museum, Halifax is a city with lots of opportunity for artists to show their work and to be exposed to contemporary art from near and far.

It is also a city with a long history of artist-led culture, a place where, if artists cannot find what they are looking for (an exhibition venue, an art magazine, a production facility, an arts council), they tend to roll up their sleeves and work to realize what was lacking. Halifax’s art history has proceeded in fits and starts, with bursts of energy that move the city along. Jeffrey Spalding (1951–2019), a former director of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia and an acclaimed artist and writer, once described cultural work in Halifax to me as about getting things—institutions, careers, collections—“to the next level.” It was a hard slog up that hill (“Halifax is set atop a hostile site,” writes Peck, “a lump of igneous rock open to the North Atlantic”), but Spalding believed that the city evolved by being dragged upward to new levels. Each success meant that, after a short breather to enjoy the view, the work could start again. That’s as good an analogy for this hard city’s art history as any I can imagine. For every victory—an art school, an art museum, an art award—there is a long battle for resources, a near-constant overcoming of resistance (from within and without Halifax’s defences), and a step-by-step slog to that tantalizing “next level.”

Nova Scotia is Latin for “New Scotland,” but for much of Halifax’s long history the powers-that-be have seemingly focused on the first syllable, “No,” as in, “No” to an art school in 1870, “No” to an art museum in 1908, “No” to a purpose-built building for that eventual museum in 1985, and so on. Sometimes, Halifax’s artists and community builders were able to turn those noes to yeses: “Yes” to the Victoria School of Art and Design in 1887, “Yes” to the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in 1975, and “Yes” to a proposal for a new Art Gallery of Nova Scotia building in 2019.

Halifax’s art and artists have alternately struggled and flourished thus, in a rhythm as predictable, if not as regular, as the tides that wash against this outcropping into the Atlantic Ocean. Halifax, Kjipuktuk, is a work in progress. There is always a new level to reach, and a new view to be appreciated, before the work starts again.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements