Halifax’s art history has rarely displayed steady progress, but rather has exhibited a series of fitful evolutions driven by circumstances and fuelled by the efforts of dedicated groups of activist citizens. Once the capital of a British colony and now the capital of a Canadian province, Halifax is a city in flux. As a military and commercial port, and as a home to five major universities, it is marked by the comings and goings of regiments, of immigrants and refugees, of students, of governments. The city often seems to have not laid down roots so much as it has been moored—secure, but still buffeted by time and tide. Founded as a military outpost, Halifax has also always seemed to be on the defensive culturally, and permanent institutions in the arts have taken a long time to be established. For example, the city’s art college was founded 140-odd years after the city itself, while the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia opened almost exactly 225 years after the first European settlers arrived in Kjipuktuk. But for more than two hundred years there have been art associations and institutions in the city. Perhaps the very mutability of Halifax has created the possibilities for sudden change, for transformative leaps of faith, that have culminated in the rich and diverse artistic communities found in the city today.

1787: The Halifax Chess, Pencil and Brush Club

The first recorded art association in British North America, remarkably, was the Halifax Chess, Pencil and Brush Club, founded in 1787 and active for thirty years. The club was founded with its purpose being the “promotion of drawing and watercolour painting (as well as chess) as polite pursuits.”

A key founding member was Richard Bulkeley (1717–1800), who arrived in Nova Scotia as aide-de-camp to Edward Cornwallis (1713–1776) in 1749 and was the most influential civil servant in Halifax until his death in 1800. Amidst his administrative, judicial, and military responsibilities, Bulkeley was also the city’s earliest patron of the arts as well as an amateur artist himself. A self-portrait by Bulkeley survives at the Nova Scotia Museum, which long-time curator and historian Harry Piers (1870–1940) dismissed in 1914 as a “wretchedly-executed, straddle-legged, chalk representation of himself.” Later critics have not been so harsh. Dianne O’Neill (b.1944) contends that “he appears to have captured in a few deft strokes the languid, sophisticated detachment of a man aware of the cultured life he left behind in Dublin and London, but proud of his accomplishments in his new land.”

1830: Dalhousie College Art Exhibition and Other Early Exhibitions

In 1830 the first public art exhibition in Atlantic Canada, and what has been claimed as “the first public exhibition of pictures ever in British North America,” was held at Dalhousie College from May 10 to 29. Organized by the school’s drawing and painting instructor, W.H. Jones (active at Dalhousie College 1829–1830), the exhibition included works by Jones, his students, and by other local artists, both amateur and professional. In what would become a theme in Halifax exhibitions through to the 1940s, the show also included European and American works loaned by local collectors.

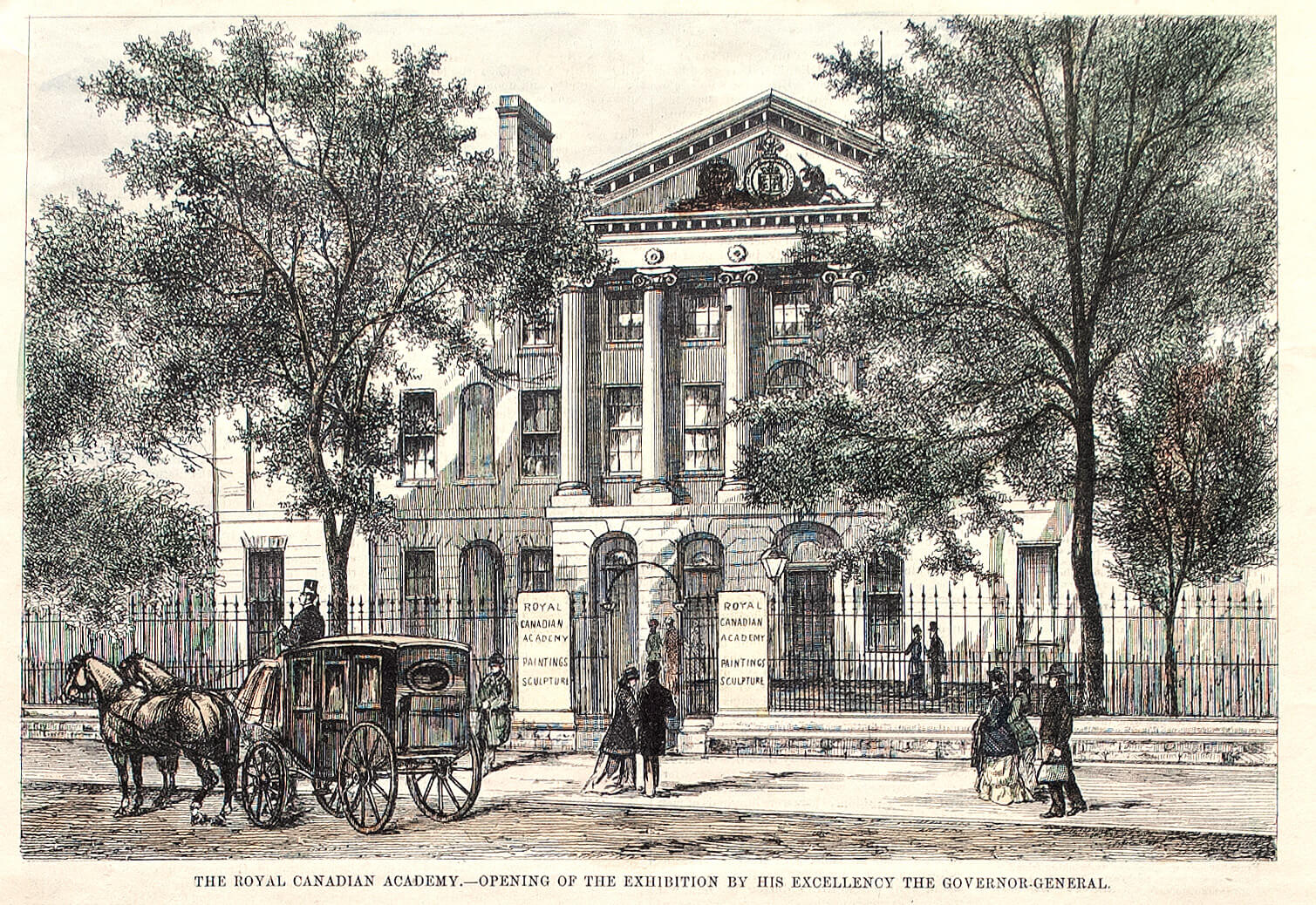

In 1848 the Halifax Mechanics’ Institute organized a large public art exhibition, which again featured the work of local artists as well as loans of European and American works from local collectors. Similar exhibitions followed, most prominently the second annual exhibition of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, held in 1881 at Province House (the Nova Scotia Legislature). The Academy never again held their exhibition in Halifax, however, as there were so few sales. At the exhibition’s opening, the governor general, the Marquis of Lorne (1845–1914), gave a speech in which he spoke about the importance of a local art school. Those remarks were to echo down the decade, inspiring a group of Halifax philanthropists to seek to make them a reality. Over the first years of the decade several events were held to raise both awareness and funds for an art school in Halifax, including a loan exhibition with numerous Asian manuscripts and artworks loaned by Anna Leonowens (1831–1915), an eventual founder of the Victoria School of Art and Design.

1831: Halifax Mechanics’ Institute and the Nova Scotia Museum

The Halifax Mechanics’ Institute was founded in 1831 as a centre for public education and “cultural improvement.” Its program included lectures on art appreciation, art classes, and travelling and locally organized exhibitions, including 1848’s large loan exhibition of work from local collections. The Institute also featured a lending library and was open to members from every part of Halifax society.

The Nova Scotia Museum was founded in 1868, with roots in both the Halifax Mechanics’ Institute and the Nova Scotia Institute of Science (founded in 1862). The Nova Scotia Museum began collecting art under its mandate as a general history museum. In the early twentieth century, its second curator, Harry Piers (1870–1940), exhaustively researched Nova Scotia’s early artists; his Artists in Nova Scotia (published in the Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society in 1914) was the first attempt at a comprehensive art history of the province.

1887: The Victoria School of Art and Design

There had been many informal schools of art instruction in Halifax, the first known dating to 1809, when John Thomson, a portrait and miniature painter, advertised his services as an art instructor in private homes or in his own studio. By the late 1800s the lack of a professional school for the training of artists was becoming a topic of conversation among artists and educational advocates. Forshaw Day (1831–1903), perhaps the most prominent Halifax artist of his era, went so far as to propose, unsuccessfully, the creation of an art college in 1870 to the Nova Scotia Board of Education. In 1881 the Marquis of Lorne (1845–1914), the governor general of the day, opened the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts exhibition in Halifax; in his remarks he referred to Halifax’s lack of an art school.

Six years later, the first steps were taken to create such an institution, not by a group of artists but by the committee that had organized events celebrating Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, which decided to continue organizing. The group mounted an exhibition and held a gala fundraiser, raising $1,600 to seed the beginning of a school named after the monarch. The Victoria School of Art and Design (VSAD) was established in 1887 by this group of local advocates and philanthropists, including Anna Leonowens (1831–1915).

The first headmaster of the college was George Harvey (1846–1910), an English painter who had emigrated to Halifax in 1881 and exhibited works at the 1881 Royal Canadian Academy of Arts exhibition. The school was small in its early years, with 75 students in its daytime classes (aimed at aspiring artists and teachers), and 135 students in its evening classes (designed as continuing education for industrial workers, artisans, and tradespeople; these classes were offered free of charge to apprentices and “others desiring to prepare themselves for industrial occupations”).

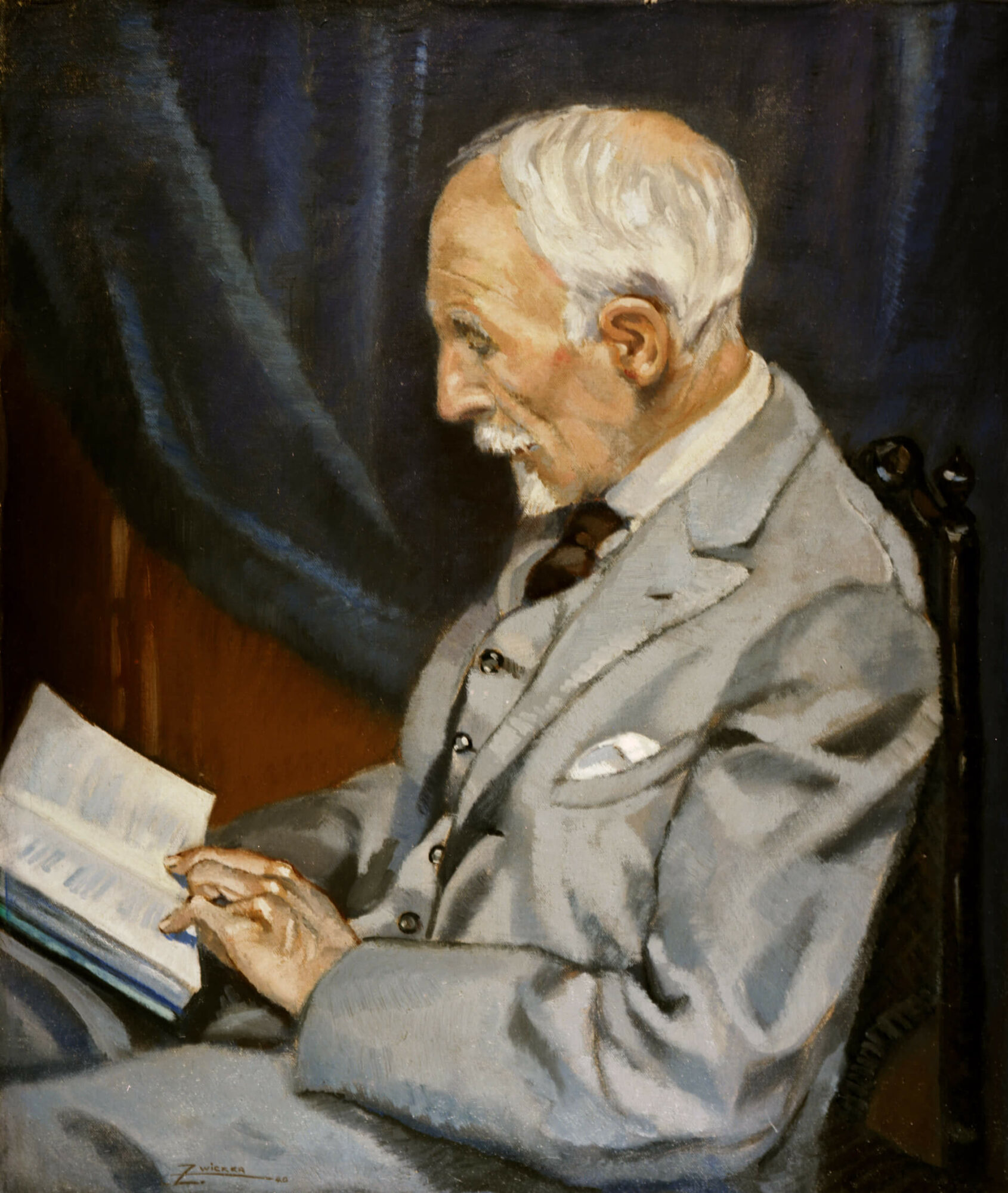

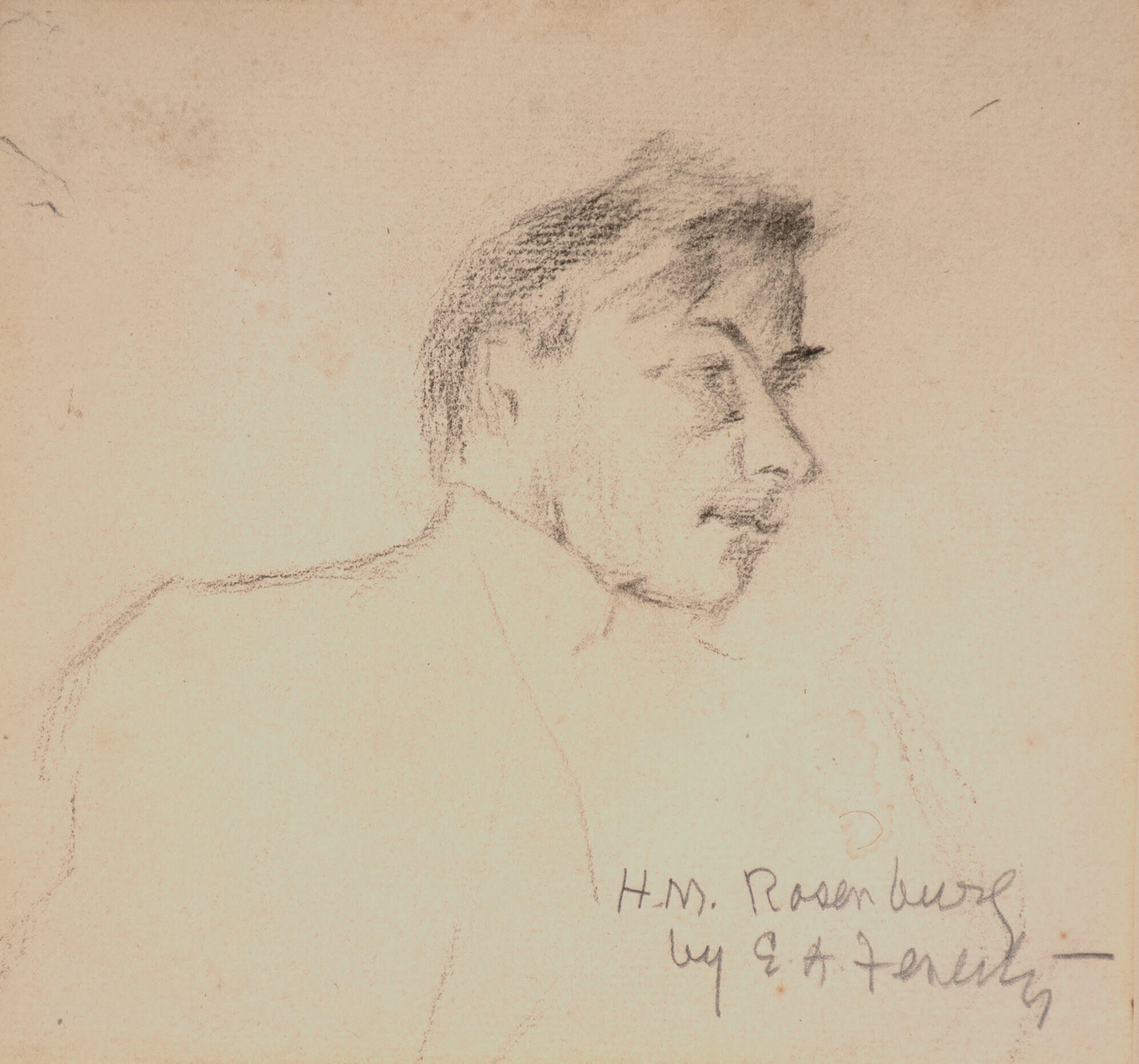

In 1895 the title of headmaster was dropped in favour of principal, and Katharine Evans (1875–1930) was hired as the first woman leader of VSAD. She was followed in 1898 by the painter Henry M. Rosenberg (1858–1947), perhaps the most accomplished artist to teach at the art school until the arrival of one of his successors, Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), who was principal from 1916 to 1919. In those early decades, the school had low enrolment, sometimes under twenty students, and the principal was often the only full-time faculty member. VSAD was renamed the Nova Scotia College of Art (NSCA) in 1925, and the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD) in 1969, before becoming NSCAD University in 2003.

1908: The Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts

The Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts (NSMFA) was founded in 1908 by a group of Haligonians, including Anna Leonowens (1831–1915) and Edith Smith (1867–1954), interested in creating an art museum in Nova Scotia’s capital city. For the more-than-sixty years it was in operation the NSMFA struggled to realize its ambitions, though it did succeed in building a modest collection and organizing numerous exhibitions. The principal of the Victoria School of Art and Design (VSAD, now NSCAD University) often served as the curator of the NSMFA, and at times the art school stored the museum’s small collection of paintings, prints, and sculptures.

Over the decades, the NSMFA worked with partner institutions such as the art college and the Nova Scotia Society of Artists (founded in 1922, originally as a branch of the NSMFA) to lobby governments for the construction of a dedicated art museum, and to raise funds to support such a project. It was also one of the initial member groups of the Maritime Art Association, although it did not have an exhibition space to participate in the Maritime Art Association’s prime function, the circulation of exhibitions. The NSMFA sold memberships at various levels, held annual meetings in Halifax, and sponsored exhibitions at the art college. In 1919, for instance, Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), then principal of VSAD and curator of the NSMFA, organized an exhibition of work by Nova Scotia-born American painter Ernest Lawson (1873–1939). Lawson, a member of the American Post-Impressionist group The Eight, had been born in Halifax, and returned often throughout the 1910s and 1920s. Lismer was able to secure funds to purchase six canvases by Lawson for the NSMFA collection.

In 1958 the NSMFA held a fiftieth anniversary exhibition at the Public Archives, drawn from its collection. The following year Nova Scotia Premier Robert Stanfield (1914–2003) announced that Lady Dunn, the widow of Sir James Dunn (and soon to marry Lord Beaverbrook) intended to fund an art gallery for Halifax. Plans were drawn up, a site was secured, and Lord Beaverbrook was named the co-custodian of the gallery that was to be modelled after his Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton. The project foundered, however, and in the end, no building of any type was built. One historian has suggested that the city and provincial governments may have balked at the prospect of supporting the ongoing operating costs of an art museum. Given the subsequent history of the quest for a purpose-built art museum in Halifax, that supposition seems likely.

It wasn’t until 1968 that the NSMFA was able to open its own space, the Centennial Art Gallery, which was located in the Halifax Citadel National Historic Site. This exhibition space displayed the collection as well as temporary shows mounted by the Centennial Art Gallery’s small staff, including its curator, Bernard Riordon (b.1947). The NSMFA operated this art gallery for ten years, until 1978, when the magazine was restored to its historical state.

When the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD) began its move from its Coburg Road location on the edges of the Dalhousie University campus, it did so in stages. The NSMFA moved into the college’s vacated Anna Leonowens Gallery in 1975, but later that year it formally dissolved, and its assets and collections were absorbed into the newly legislated Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, which continued to occupy the former NSCAD space, then owned by Dalhousie University.

1922: The Nova Scotia Society of Artists

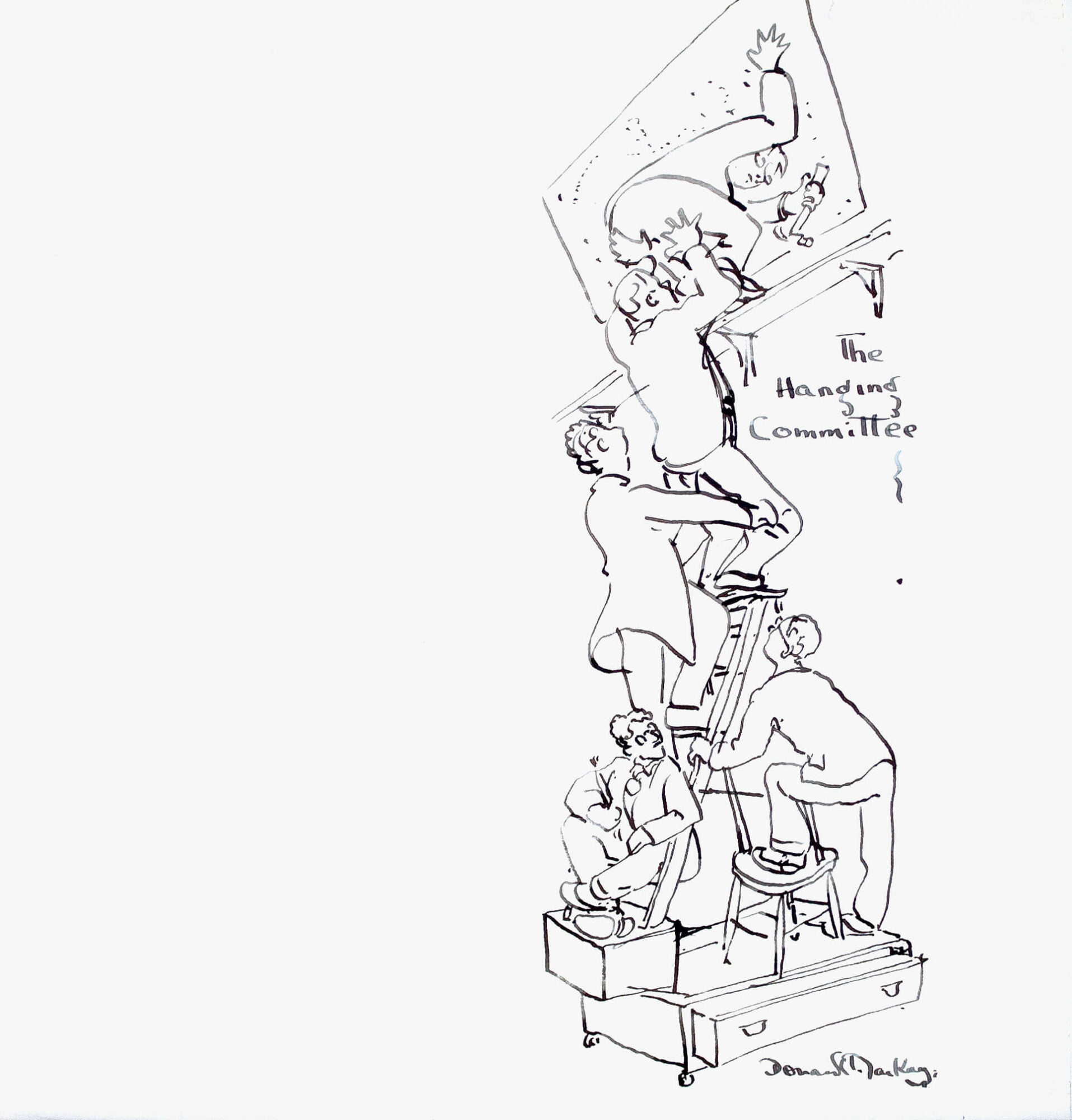

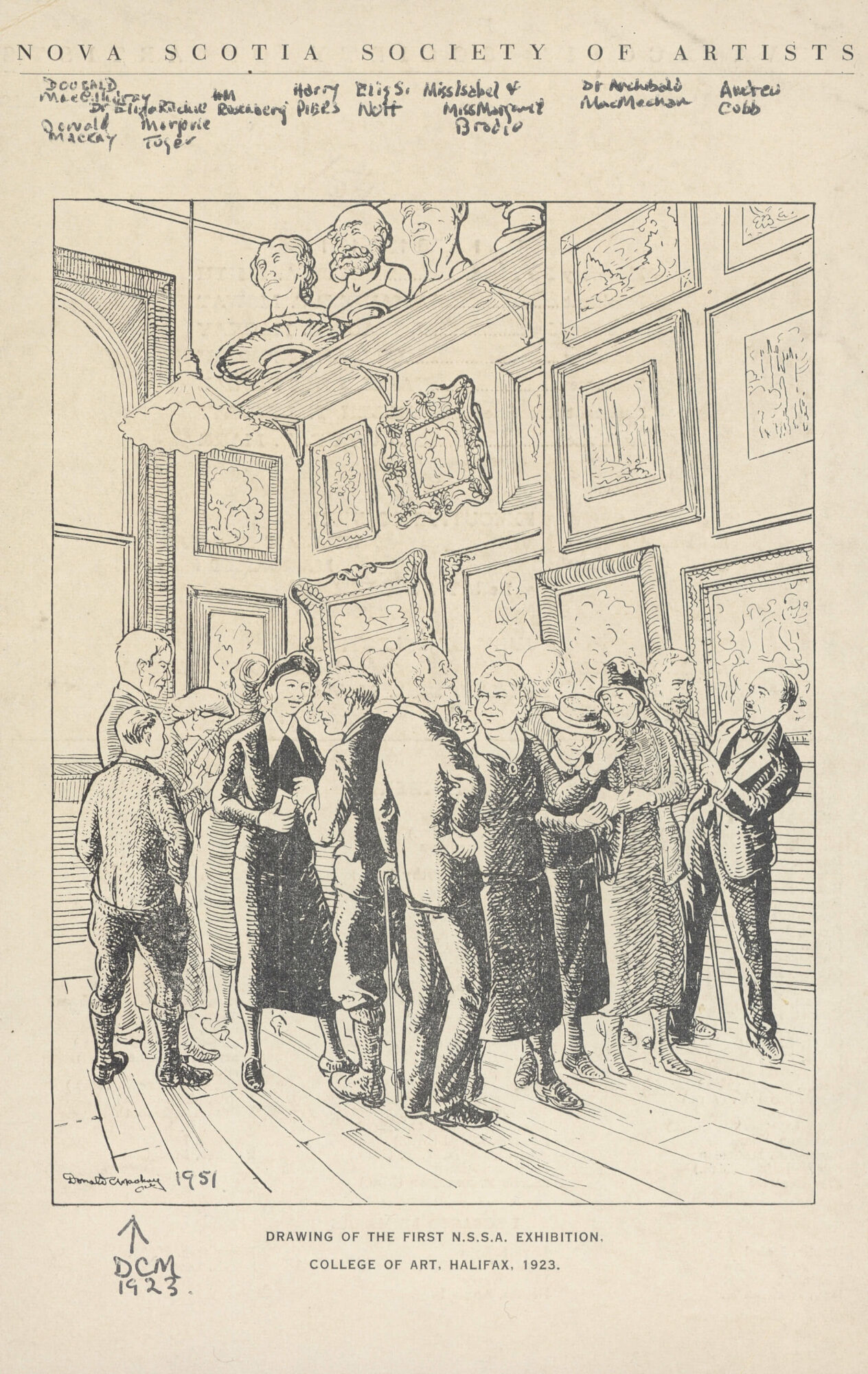

The most important art association for Halifax art and artists in the early twentieth century was the Nova Scotia Society of Artists (NSSA), founded in 1922, followed closely in importance by the Maritime Art Association, founded in 1935. The NSSA mounted annual exhibitions in Halifax for fifty years, and throughout its history was a strong advocate for the creation of a permanent art gallery for Nova Scotia. For years it was the sole artist support organization in Nova Scotia. It disbanded in 1974, as its mandate as an exhibition society seemed more and more anachronous in a city with a growing cohort of public galleries.

The most popular exhibitions in Halifax for a half-century were the Nova Scotia Society of Artists Exhibitions that were held annually from 1923. They provided a record of artistic activity in Nova Scotia that is unrivalled in its breadth: more than 4,000 paintings and other artworks were exhibited by 604 artists over 50 years. The first exhibition was held at the Victoria School of Art and Design, and shows were held at the art school annually until 1933, when the exhibition was moved to the newly constructed (and reportedly fireproof) Lord Nelson Hotel. Over the next four decades the exhibition moved from the Lord Nelson to the Halifax Memorial Library, back to the art school, and, from 1967, to the Centennial Art Gallery and the Saint Mary’s University Art Gallery.

1925: The Nova Scotia College of Art

The school that became present-day NSCAD University was still called the Victoria School of Art and Design when Elizabeth Styring Nutt (1870–1946) arrived in Halifax in 1919 to replace Arthur Lismer (1885–1869) as principal. Like Lismer, Nutt was a graduate of the Sheffield School of Art, though she was much more conservative in her methods and attitudes than was the future Group of Seven member. She was hired on Lismer’s recommendation, despite their differences, because he felt she would be able to work with the conservative board that had frustrated many of his efforts to advance the art school. As John A.B. McLeish wrote in his study of Lismer, “[Nutt] had, as Lismer knew, a personality of great strength and aggressiveness which would drive its way along to some achievements in art teaching in Halifax which he himself had not been able to accomplish.”

Nutt ruled the art school with that strong personality until 1943. In 1925 she changed the name of the school to the Nova Scotia College of Art (NSCA), dropping the “design” from its designation because, as she held, “with the advance of the last quarter century Art is recognized as one, so that the present title is all inclusive.” Under Nutt the school increased its enrolment and local profile, but it remained a conservative bastion, artistically eclipsed by the program at Mount Allison University in Sackville, New Brunswick, led from 1935 by former NSCA teacher Stanley Royle (1888–1961). Another Sheffield graduate, Royle was hired by Nutt in 1931, then fired by the NSCA in 1934 after repeatedly clashing with the principal over his teaching methods. That he was receiving popular and critical acclaim that eclipsed her own may have played a part in his departure.

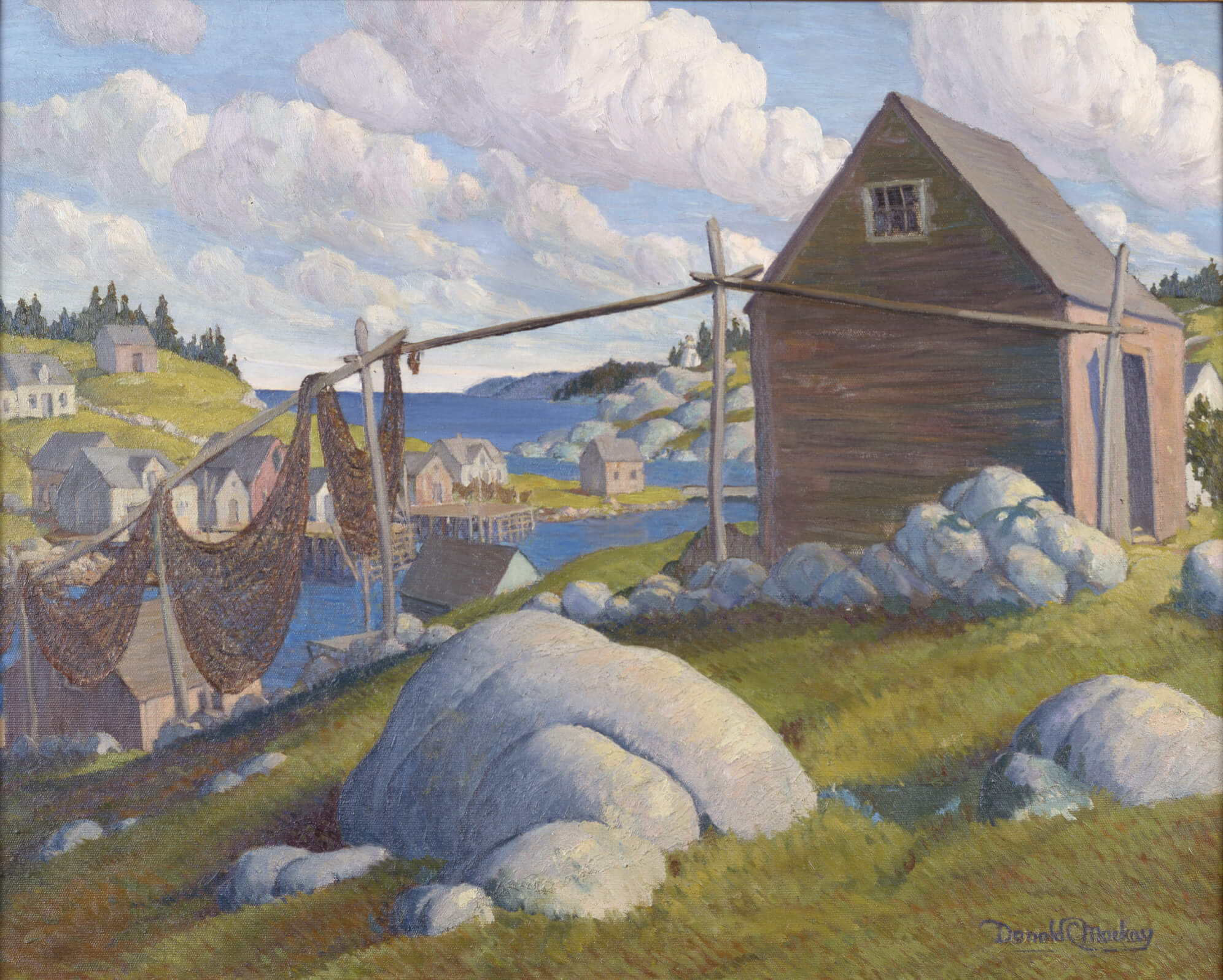

Nutt retired in 1943, but it was not until 1945, and the end of his service as an official Canadian war artist, that her permanent replacement, Donald Cameron (D.C.) Mackay (1906–1979), was hired. Mackay was a graduate of the NSCA and had studied with Lismer at the University of Toronto. Lismer had been consulted by the NSCA board of governors and, while he had made several suggestions, Mackay was not among them. Lismer was critical of what he saw as the continued conservatism of the art college, writing that the NSCA was “completely separated from what is going on in art education today.” He laid the blame squarely on the institution, not the students: “there is a lot of talent but it is killed in its inception by the training.”

Lismer had been hoping for an innovator, but Mackay continued Nutt’s conservative program and renewed the college’s emphasis on commercial art. Mackay was an active artist, though with little profile beyond Halifax. He also taught art history at Dalhousie University from 1938 to 1971 and was honorary curator of the Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts from 1945 to 1955. Mackay oversaw the move of the NSCA to a new building near the Dalhousie campus in 1957. As under Nutt, the NSCA under Mackay concentrated on landscape painting, portraits, and commercial design.

1935: The Maritime Art Association

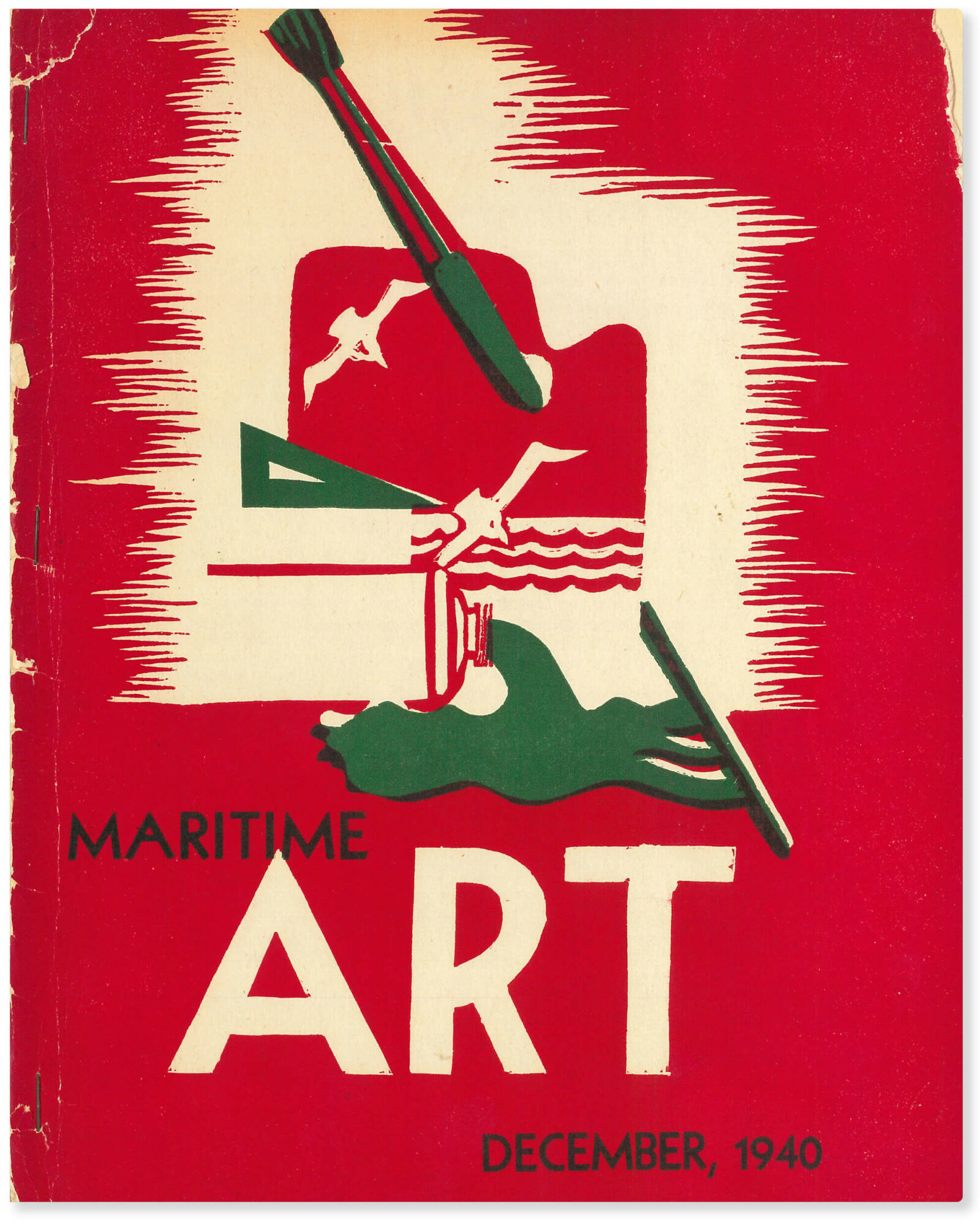

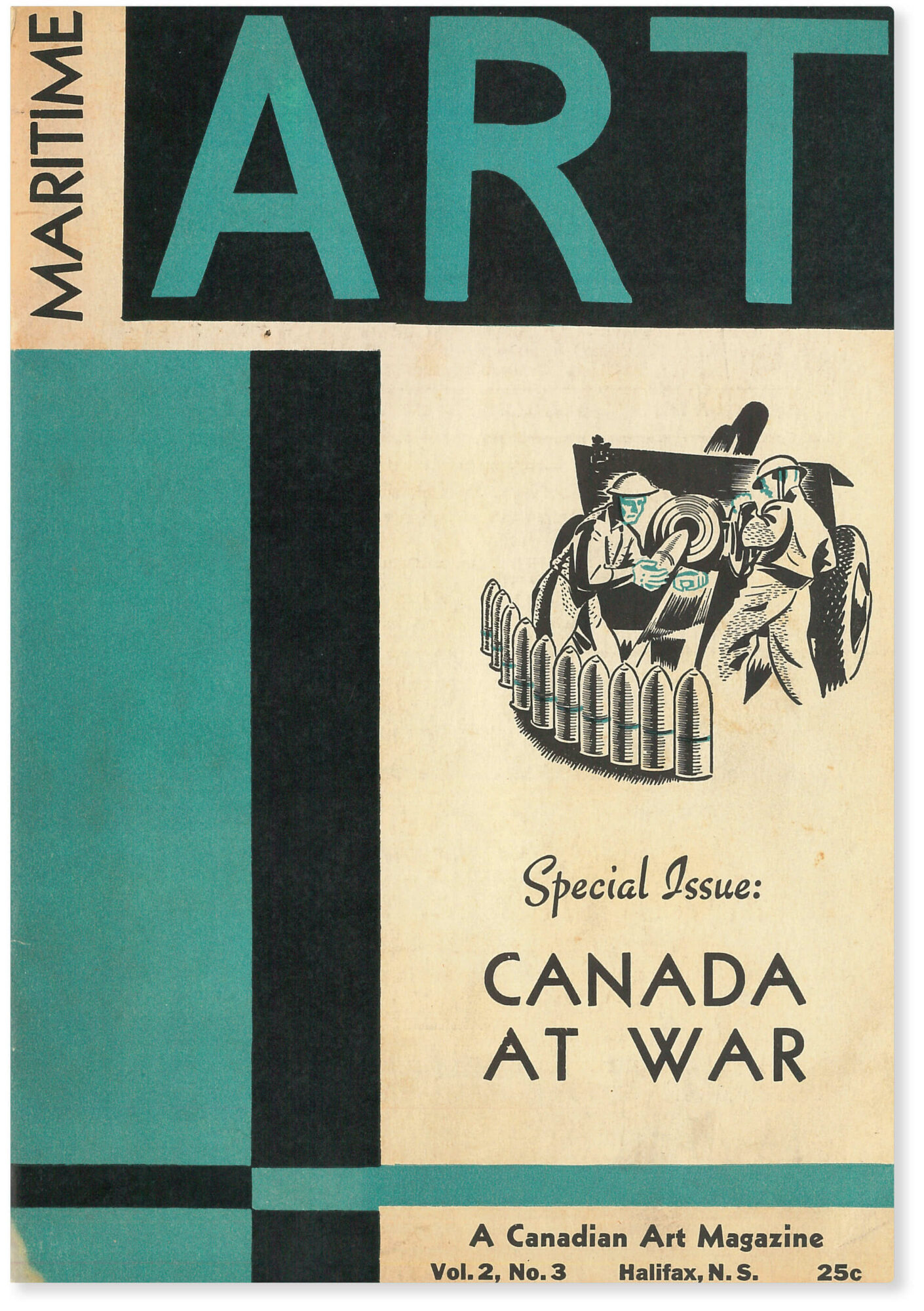

The first magazine dedicated solely to the visual arts was a quarterly journal called Maritime Art: The Journal of the Maritime Art Association, launched in 1940. It featured articles about the arts in Atlantic Canada, interviews, and exhibition reviews. Its publisher was the Maritime Art Association (MAA), founded five years earlier with the mandate of promoting art throughout the eastern provinces. The MAA was founded under the initiative of Walter Abell (1897–1956), an art history professor and curator at Acadia University in Wolfville; the eleven initial member groups of the association included the Nova Scotia College of Art and the Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts. According to the historian Sandra Paikowsky, the MAA was “the first Canadian regional alliance of art clubs and societies, public schools, universities, social organizations, service and civic groups, artists, art students and anyone else interested in art.”

One of the association’s longest-running programs was its travelling exhibitions. At least eight annually (often borrowed from the National Gallery of Canada) travelled throughout the region. The MAA also mounted annual exhibitions of regional artists that toured to venues across the Maritimes. Paikowsky notes that through these efforts, “the MAA created an infrastructure for the promotion and dissemination of art in the Maritimes.” After its demise in the late 1960s, that infrastructure was later utilized by the Atlantic Provinces Art Circuit (an association of regional galleries for touring their exhibitions among their venues) and its successor, the Atlantic Provinces Art Gallery Association.

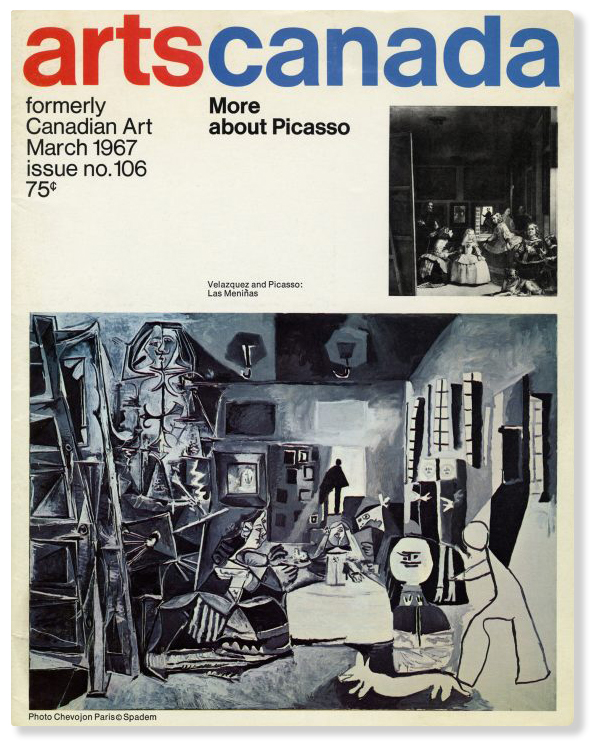

Maritime Art was edited by MAA president Walter Abell until 1943, when Abell moved it to Ottawa under the aegis of the National Gallery of Canada. Maritime Art was renamed Canadian Art that year. In 1967 the magazine changed its name to artscanada, and in 1983 it was changed back to Canadian Art. In 2021 the magazine ceased publication.

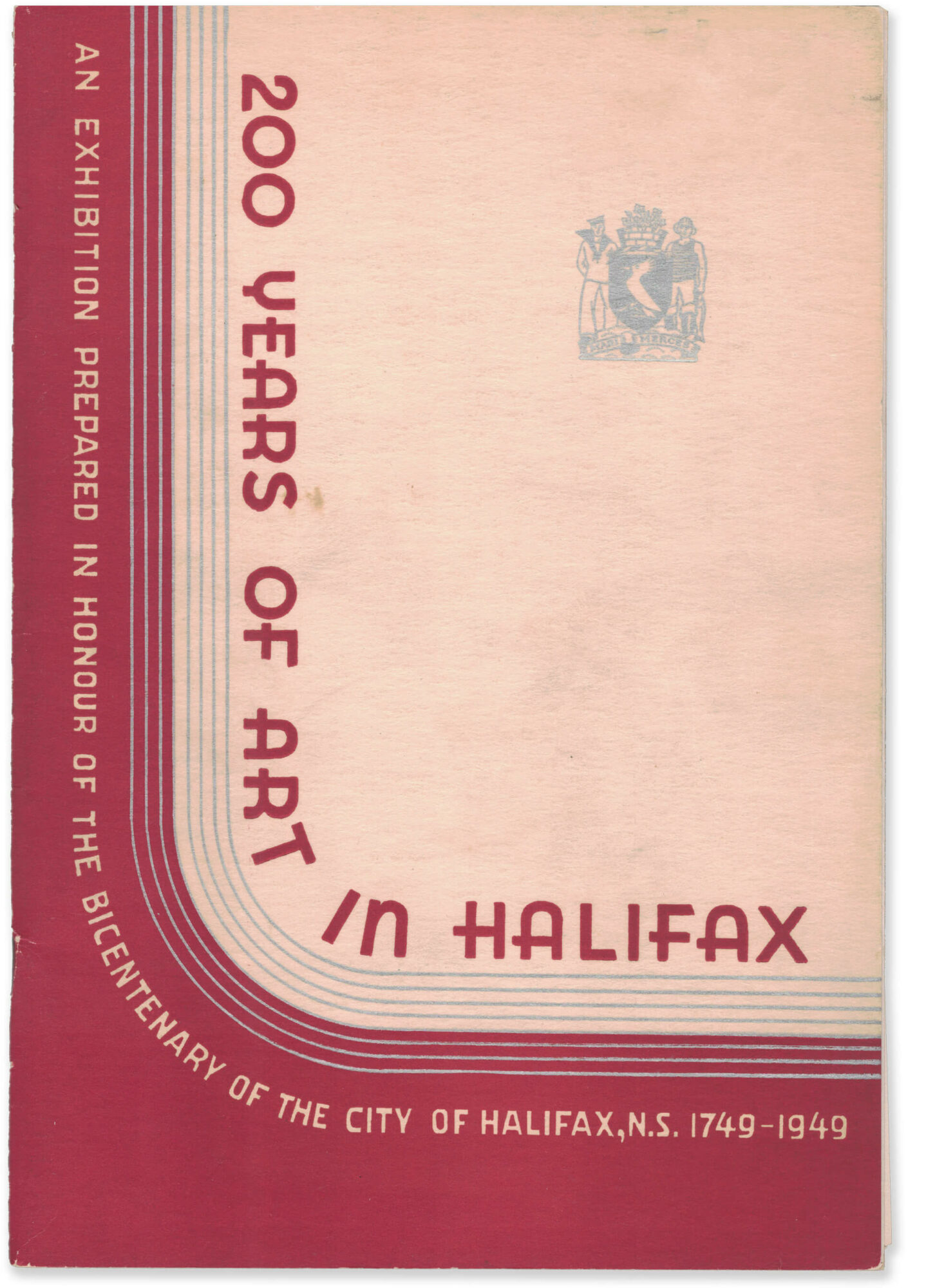

1949: 200 Years of Art in Halifax

In 1949 a loan exhibition that harked back to the first exhibitions of the nineteenth century was mounted in honour of Halifax’s bicentennial. Drawing on private and public collections in the city, it featured works that stretched back to 1750 and included numerous contemporary works by living artists.

The organizers were individuals representing the Nova Scotia Society of Artists, the Nova Scotia College of Art, the Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts, and Dalhousie University. They held the show at the newly constructed Queen Elizabeth High School and presented the opportunity, as the committee stated in the catalogue introduction, “to walk back through the years and recover something of the flavour of the stages of the city’s development.” The exhibition was limited to views of the city and harbour, and to portraits of “natives, citizens, or celebrities painted in the city.” Despite these restrictions, the exhibition featured 275 works of art and represented most of the best-known figures from the city’s art history. The committee even secured the loan of a self-portrait by Gilbert Stuart Newton (1794–1835) from the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, despite the artist’s tenuous link to the city (Newton was born in Halifax and lived there as a child, but his family moved to Boston in 1803, where he trained as an artist with his famous uncle Gilbert Stuart [1755–1828]; he never visited the city of his birth). Other notable loans included Elevator Court, Halifax, 1921, by Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970), from the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario); and Olympic with Returned Soldiers, 1919, by Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), from the National Gallery of Canada.

1953: The Dalhousie Art Gallery

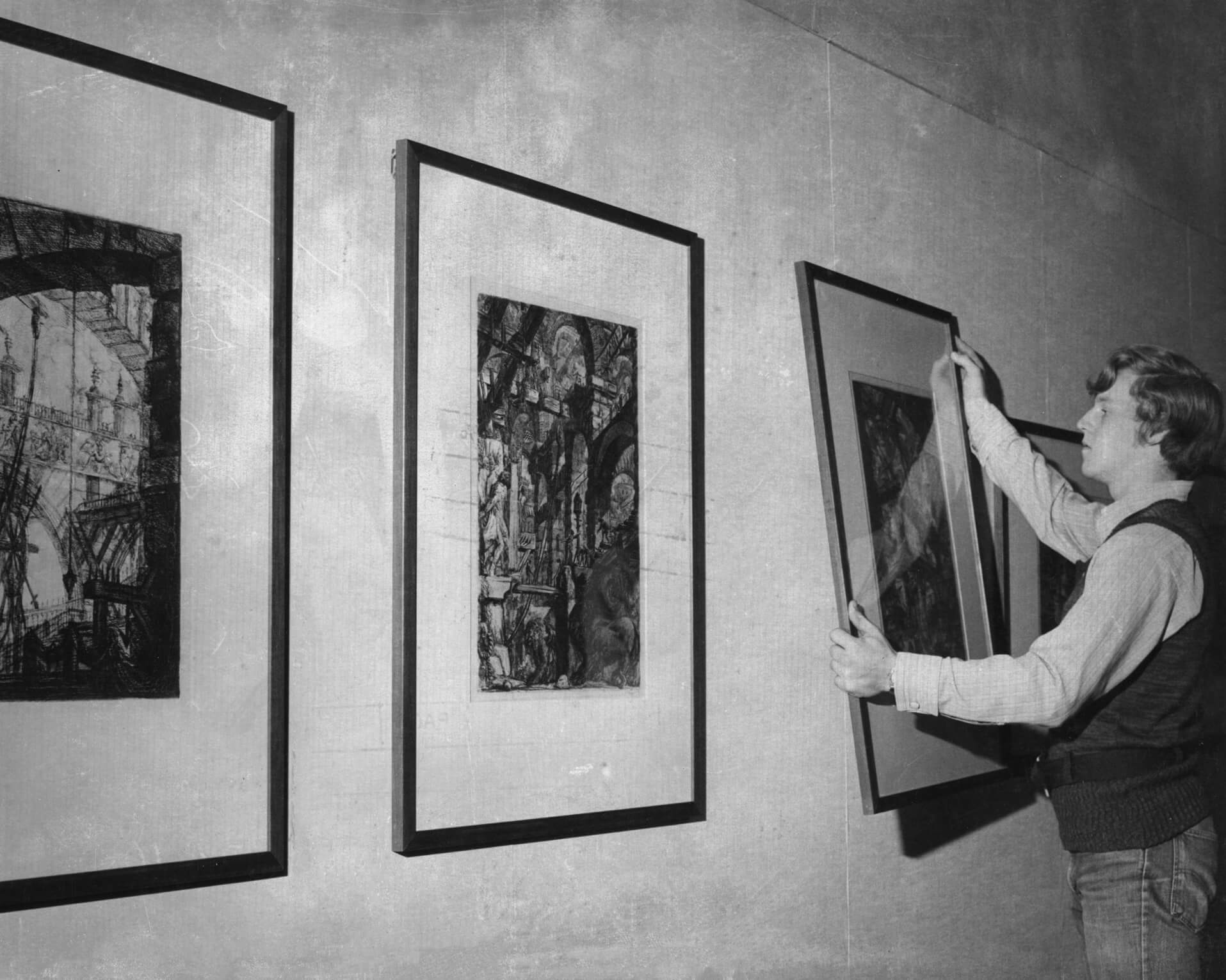

By the 1970s, Halifax had five university art galleries. The oldest was the Dalhousie Art Gallery; established in 1953, it was also the first public art gallery in Halifax.

The Dalhousie Art Gallery made an immediate impact in the city, as for a decade it was the only dedicated venue for art exhibitions. In 1955 the gallery inaugurated their Know Your Artist series with a solo exhibition by Halifax painter Ruth Salter Wainwright (1902–1984). The series was intended to introduce local audiences to established local artists, and it was the first such program in Nova Scotia’s history. In 1956 the program was expanded to include a second group exhibition of “young and somewhat revolutionary” artists.

Until 1967 the Dalhousie Art Gallery was the only public gallery in Halifax. Even with the opening of the Centennial Art Gallery by the Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts in 1967, the Dalhousie Art Gallery remained the most important contemporary art venue for local artists until well into the 1970s. In 1971 it opened in the new Dalhousie Arts Centre, a modernist building designed by Halifax architect Charles Fowler. Its influential director/curators have included Bruce Ferguson (1946–2019), Gemey Kelly, Susan Gibson Garvey (b.1947), and Peter Dykhuis (b.1956). In 2022, Pamela Edmonds took on the directorship of the Dalhousie Art Gallery.

1967: Africville

One night in the spring of 1967 (the exact date remains forgotten), Seaview African United Baptist Church was destroyed by workers from the City of Halifax. This was part of an effort that had begun in 1962 to move the residents out of the community known as Africville, a historically Black settlement since the early 1800s. Defended at the time as “urban renewal,” the destruction of the church has lately been recognized as a racist act that destroyed a unique cultural entity.

The razing of Africville saw the loss of historically and personally significant cultural objects and artifacts, including works of art. While researching his groundbreaking 1998 exhibition In This Place: Black Art in Nova Scotia, curator David Woods (b.1959) uncovered the history of Africville-born artist Edith Hester McDonald-Brown (1880–1956). Although little is known about her, McDonald-Brown is believed to be the first recorded Black female painter in the history of Canadian art and may have travelled to Montreal to attend art school. Highland Cattle, 1906, which depicts a herd of cows on a hillside landscape, is one of only four of her works still in existence. Others were most likely lost during the forced relocation of Africville’s residents. The under-documentation of McDonald-Brown’s work and significance underscores the general lack of public familiarity with the history of Black Canadian art production. As Woods states, “people tended to ignore that there were artists creating masterpieces equal to the work of anyone else at that time.”

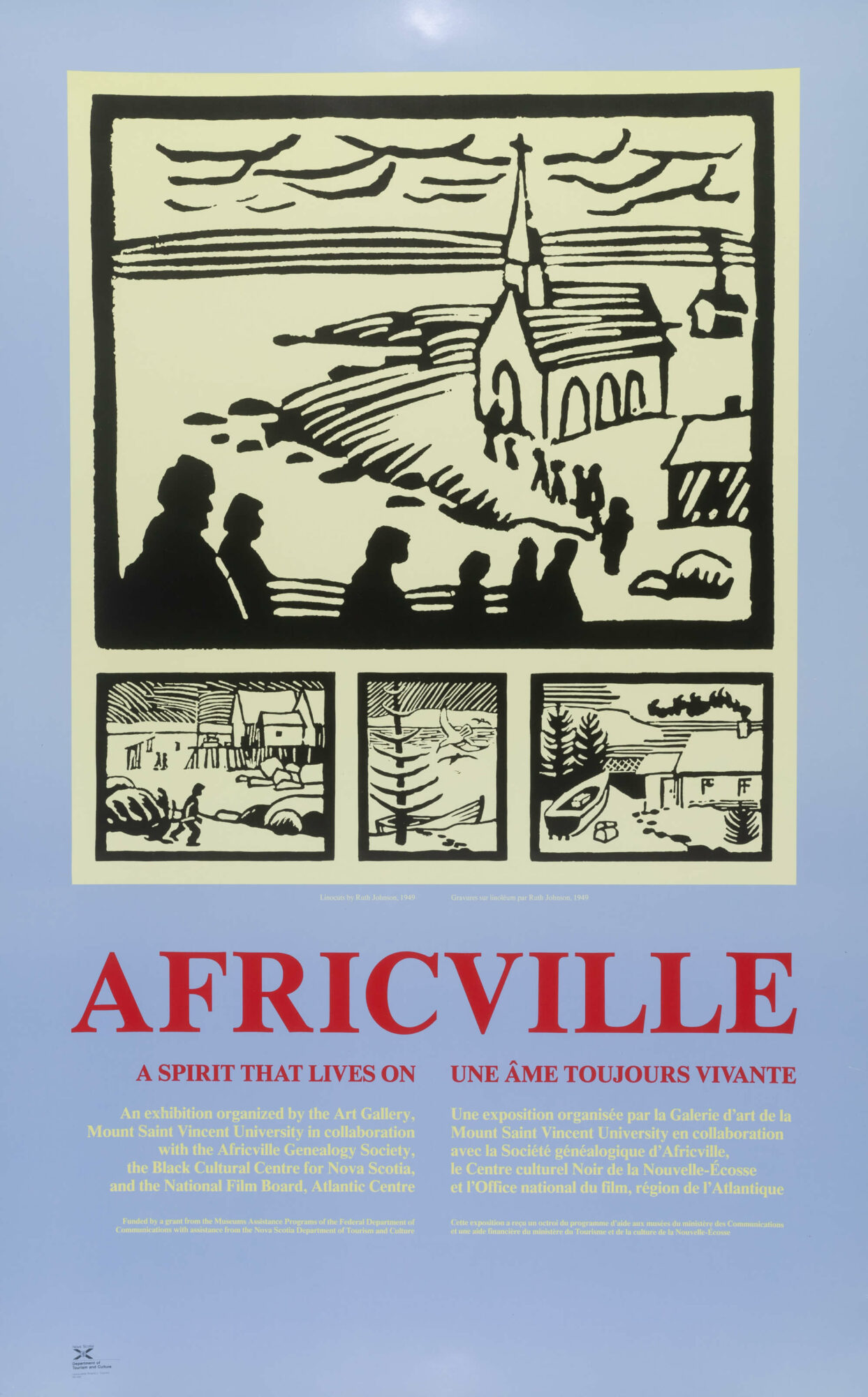

The uniqueness of Africville was documented in 1989, when the MSVU Art Gallery, the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia, and the Black Genealogical Society created the exhibition Africville: A Spirit that Lives On to celebrate and acknowledge “the legacy and spirit of Africville and set a benchmark for collaborative, community driven exhibitions.” In 2019 the MSVU Art Gallery and the original partners were joined by the Africville Museum to remount and reflect on the exhibition.

In 1991 director Shelagh Mackenzie (1937–2006) produced the short film Remember Africville for the National Film Board of Canada. The site was declared a National Historic Site of Canada in 1996, and it is cited as “a site of pilgrimage for people honouring the struggle against racism.” In 1997 Toronto jazz musician Joe Sealy (whose father was born in Africville) won the Juno Award for Best Contemporary Jazz Album for Africville Suite, which featured cover art by David Woods (b.1959). The site is now home to a recreation of the Seaview African United Baptist Church, which houses the Africville Museum.

1969: The Nova Scotia College of Art and Design

In 1967 thirty-one-year-old artist Garry Neill Kennedy (1935–2021) was named the first president (a change in title for the role formerly known as principal) of the Nova Scotia College of Art. Kennedy, a Canadian who had been teaching in the United States, immediately began to modernize the school. At the start of the 1968–69 school year he fired four long-time contract faculty and hired ten young artists—a group of mostly Americans—who were more interested in the contemporary issues roiling the art world, specifically Conceptual art, Post-Minimalism, and emerging technologies such as video art. With hires including Gerald Ferguson (1937–2009), David Askevold (1940–2008), Patrick Kelly (1939–2011), and Jack Lemon (b.1936), Kennedy transformed what had been a small conservative school into one that came to be known internationally and that could be legitimately described as “a hotbed of activity in the latest modes of art creation.”

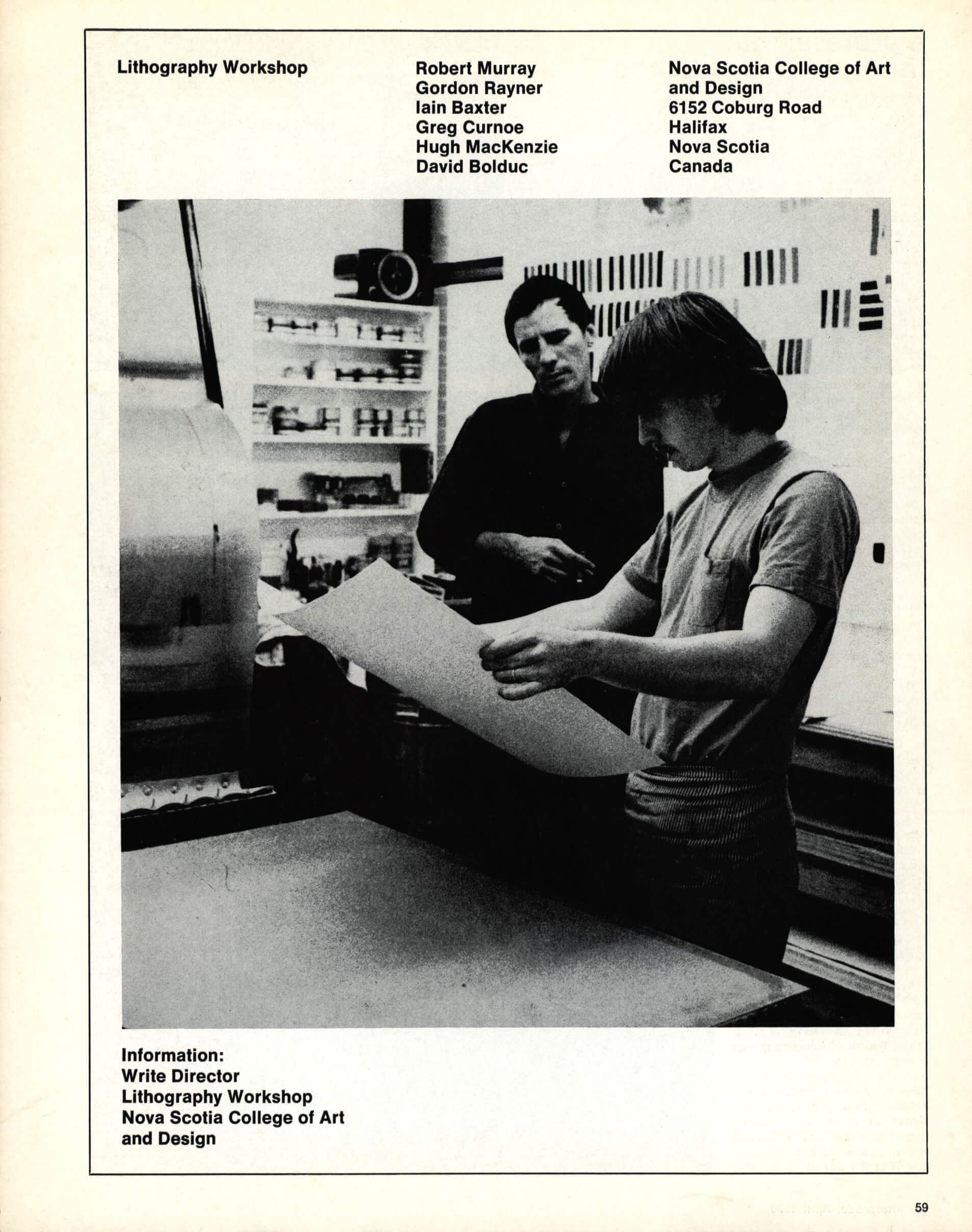

Kennedy led an effort to modernize the school’s facilities and programs, resulting in the construction of a six-storey addition to their existing building; opened in 1968, the addition more than tripled the footprint of the college. That facility included two art galleries: the Mezzanine Gallery and the Anna Leonowens Gallery. In 1969 “design” (dropped by Elizabeth Styring Nutt [1870–1946] when she was principal) was added back into the school’s name, and the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD) was awarded degree-granting status. In 1973 NSCAD established its Master of Fine Arts degree program. NSCAD continued to grow in size and reputation, fuelled in no small part by innovative programs such as David Askevold’s Projects Class, the NSCAD Lithography Workshop (1969–76), the NSCAD Press, the exhibition programming in its two galleries, and the college’s active Visiting Artists Program.

These five programs worked in unison to create the brief era of NSCAD’s golden age. Visiting artists were key to all of them: they would create projects for Askevold’s seminar, the results of which were often shown in the galleries. They would also teach classes, have exhibitions, and perhaps make a print for the Lithography Workshop or oversee the production of a book. Kennedy deliberately kept faculty positions vacant to pay for the visitors, and almost exclusively used visitors as faculty in the school’s summer programs. Sabbaticals were covered by visiting faculty as well, creating a constant flux in the teaching that lent an energy to the school’s programs.

NSCAD’s Anna Leonowens Gallery had opened in 1968 with an exhibition called Five Canadians, curated by Gerald Ferguson. NSCAD also opened its Elizabeth Styring Nutt Gallery (later known simply as the Mezzanine) that same year. The galleries had an active exhibition program, hosting such notable events as the first public exhibition of work by Dan Graham (1942–2022), and the first exhibitions in a public art gallery in North America of works by Gerhard Richter (b.1932) and A.R. Penck (1939–2017). The galleries were run initially by Gerald Ferguson, and eventually they were overseen by a remarkable group of curators that included Charlotte Townsend-Gault, Ian Murray (b.1951), and Allan Harding MacKay (b.1944).

In 1972 the college instituted a publishing program called the NSCAD Press. Initially overseen by Kasper König (b.1943), and then by Benjamin H.D. Buchloh (b.1941), the NSCAD Press published numerous monographs by internationally renowned artists, such as Claes Oldenburg’s Raw Notes (1973), Simone Forti’s Handbook in Motion (1974), and Donald Judd’s Complete Writings, 1959–1975 (1975).

The Lithography Workshop, initially directed by Jack Lemon, saw artists and students collaborate with master printers, including Wallace Brannen (1952–2014) and Bob Rogers (b.1944), to create a series of original lithographs that were sold to fund NSCAD programs. In its seven-year run (1969–76), the Workshop produced prints by artists as renowned as Lawrence Weiner (1942–2021), Joyce Wieland (1930–1998), Vito Acconci (1940–2017), Greg Curnoe (1936–1992), Sol LeWitt (1928–2007), and Robert Ryman (1930–2019), among many others.

In 1972 NSCAD had began to move into vacant historic buildings in downtown Halifax, a process that was completed in 1978 with the opening of NSCAD’s new Duke Street campus. This move greatly increased the school’s footprint, as well as saving a block of historic buildings from being razed to make way for a planned four-lane highway.

NSCAD (now known as NSCAD University) remains independent despite a spate of university mergers in Halifax, and remains one of the pillars of the Halifax art community.

1970: The Halifax Conference

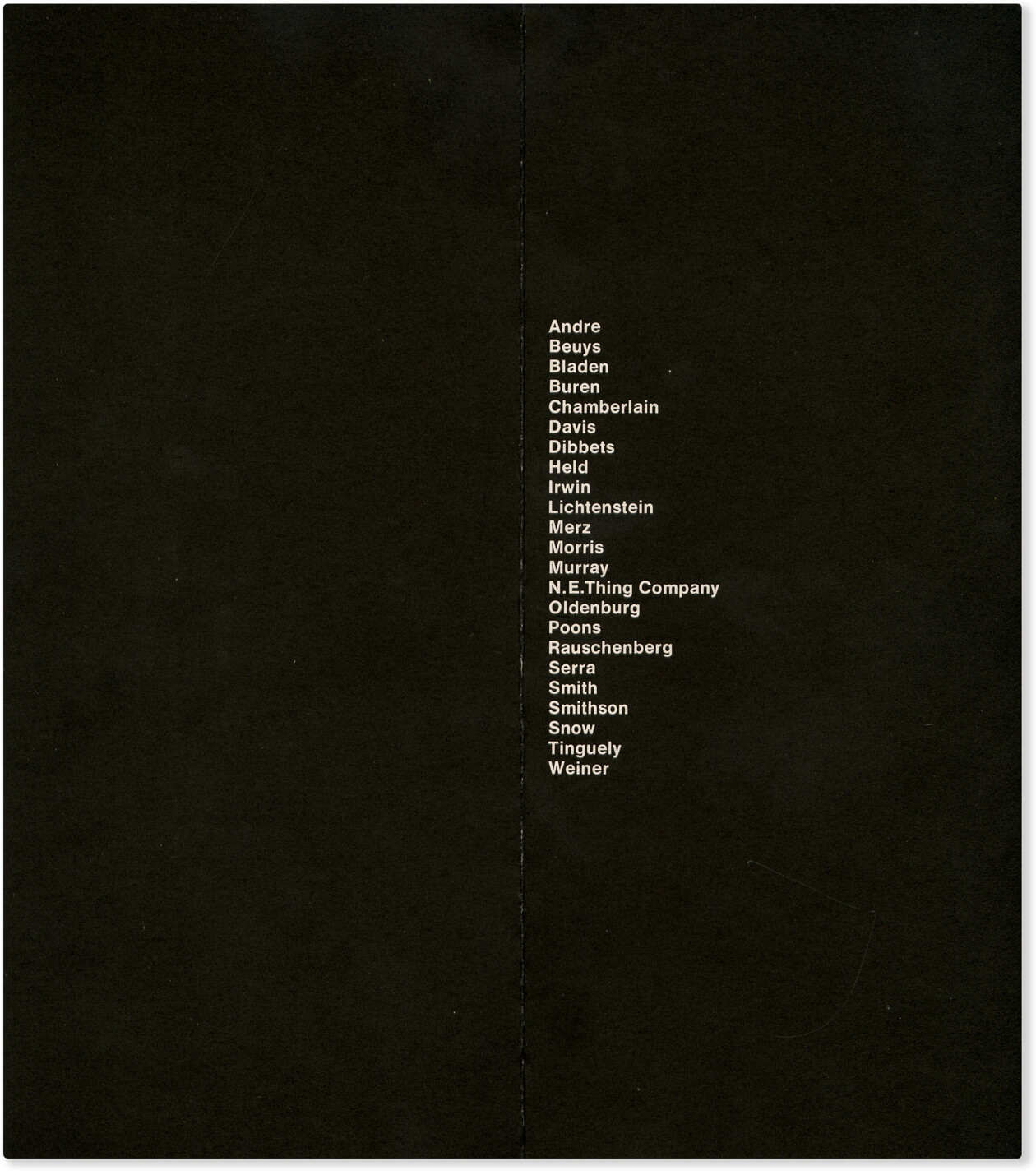

An idea developed by New York freelance curator Seth Siegelaub (1941–2013), the Halifax Conference was a landmark two-day event held from October 5 to 6, 1970, that brought some of the most renowned contemporary artists of the day to Halifax for an informal symposium on contemporary art. Garry Neill Kennedy (1935–2021) secured funding for the project from the cigarette company Benson & Hedges, and twenty-five artists were invited to Halifax. The list of participants who arrived was impressive: Carl Andre, Joseph Beuys, Ronald Bladen, Daniel Buren, John Chamberlain, Gene Davis, Jan Dibbets, Al Held, Robert Irwin, Mario Merz, Robert Morris, Robert Murray, N.E. Thing Co. (IAIN BAXTER& and Ingrid Baxter), Richard Serra, Richard Smith, Robert Smithson, Michael Snow, and Lawrence Weiner. The event was to be held over a two-day period, with the discussion happening in a room closed to the public, but broadcast to the auditorium where students, faculty, and members of the public were invited to watch.

Early on there was controversy when Robert Morris, Richard Serra, and Robert Smithson decried the separation of artists and students, deeming it elitist. They also did not like the school’s plans to publish the transcripts and left Halifax in protest. The conference was also criticized by a group led by Lucy Lippard (b.1937) who protested the lack of women as participants.

The event took on a large role in the mythology of the “Conceptual art years” at NSCAD, and it brought the school to wider attention. As Kennedy recalled, “the conference certainly put the College on the international art map.”

1971: Saint Mary’s University Art Gallery and MSVU Art Gallery

Both Saint Mary’s University and Mount Saint Vincent University founded art galleries in 1971. These joined the Dalhousie Art Gallery as important centres for exhibiting and collecting work made by Halifax artists. They also brought in exhibitions from across Canada, increasing the exposure of Halifax artists to contemporary trends.

The university art galleries played an important role in developing curatorial practice in the city, with such programs as MSVU Art Gallery director Mary Sparling’s “exhibition officer” position, a one-year curatorial apprenticeship that provided rare entry-level experience in galleries.

Throughout the 1990s the two galleries were also instrumental in developing programming that highlighted the work of both established and emerging Halifax artists. At the Saint Mary’s University Art Gallery, Leighton Davis (b.1941) and Gordon Laurin (b.1961) developed programs that included feature group shows of emerging artists as well as solo exhibitions of locally and regionally established artists. MSVU Art Gallery’s focus was on art by women, and under Sparling and, later, Ingrid Jenkner (b.1955), the gallery generated many solo exhibitions by Halifax artists such as Nancy Edell (1942–2005), Kelly Mark (b.1967), and Amanda Schoppel (b.1974), to name but a few. Throughout the 2000s the Saint Mary’s University Art Gallery under director/curator Robin Metcalfe was instrumental in bringing fine crafts into the gallery, as well as promoting the work and careers of 2SLGBTQI+ artists. Metcalfe retired in 2021.

1974: Eyelevel and Artist-run Centres in Halifax

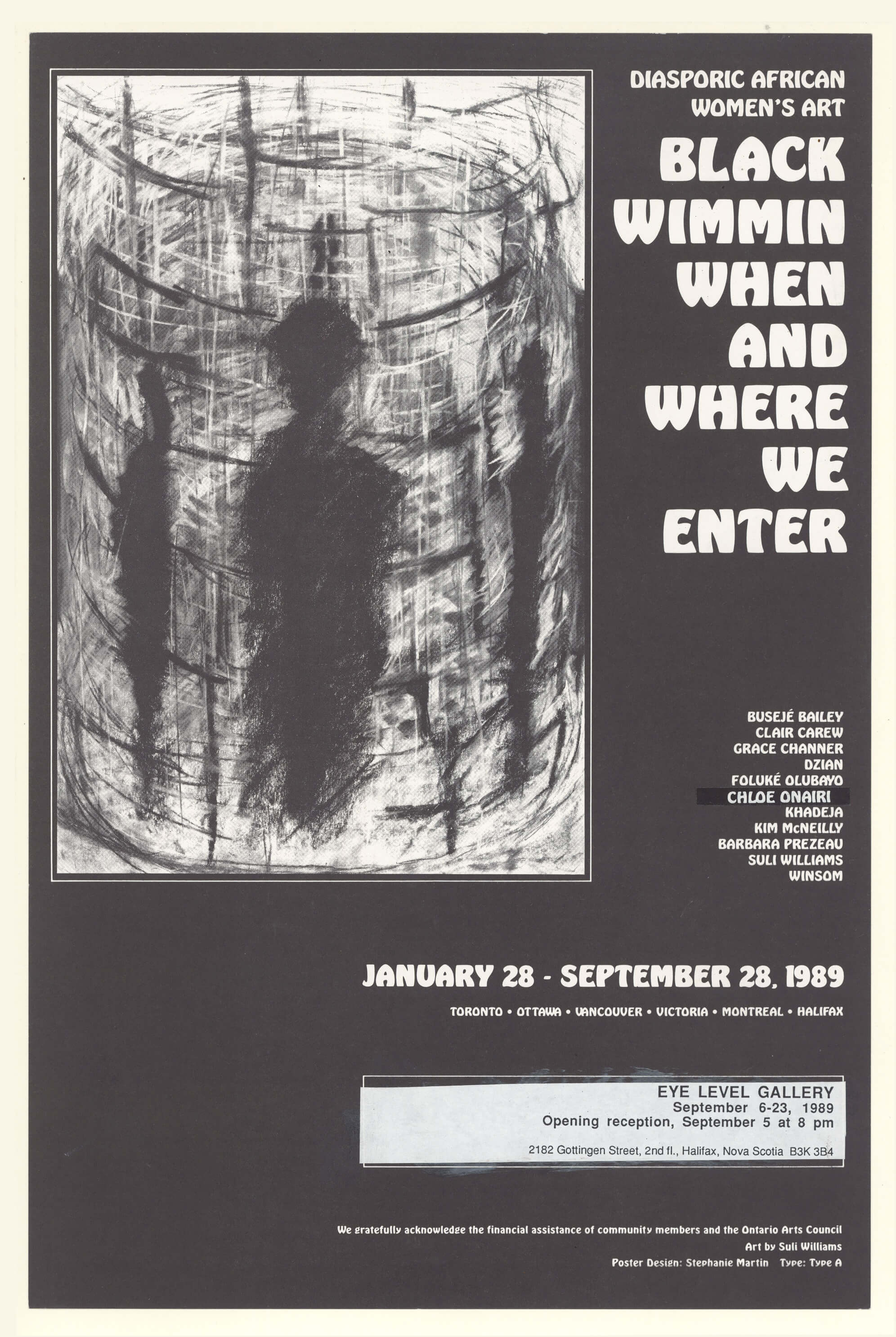

Despite the number of public art galleries in the city, many artists still felt that there was a lack of exhibition opportunities, leading to the founding of both Eye Level Gallery Society (now Eyelevel) and the Atlantic Filmmakers Cooperative in 1974. The Centre for Art Tapes followed in 1979.

As one of Canada’s oldest artist-run centres, Eyelevel has had a long and influential role as a sort of laboratory for contemporary art in Halifax. Originally founded by artists associated with the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD), Eyelevel maintained a strong connection with NSCAD faculty, many of whom were active on the gallery’s boards and committees. Subsequent artist-run centres in the city were the OO Gallery, which was briefly active in the early 1990s, and the Khyber Centre for the Arts, which was established in 1995.

The Khyber, in particular, served as a centre for young artists due to its outsider status (in its early years it received no public funding) and unorthodox business model: it was financed by the operation of a bar and music venue. It was central to the Halifax music scene of the mid-1990s, when Halifax briefly had the reputation of being “the New Seattle” and musical artists such as Sarah MacLachlan, Sloan, Jale, and Thrush Hermit rose to prominence.

The newest entrant into the artist-run milieu is The Blue Building, an artist-led gallery founded and directed by Halifax artist Emily Falencki (b.1972), which opened in 2021. Its innovative model includes curated group exhibitions and a group of core artists.

1975: The Art Gallery of Nova Scotia

The largest art gallery in Halifax is the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (AGNS). Somewhat ironically, it is also among the youngest. Although its roots date back to the founding of the Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts in 1908, the gallery first opened to the public as the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in 1975, occupying the newly vacated gallery spaces of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD) after the art school moved downtown.

The first exhibition at the new site was a retrospective exhibition of the work of LeRoy Zwicker (1906–1987), one of the prime movers behind the creation of a public art gallery for Halifax. (LeRoy and his wife, Marguerite, went on to be the lead donors for the capital campaign that would result in the opening of the gallery’s first permanent home in 1988.)

By 1978 the AGNS had expanded into most of NSCAD’s former space, which the art school had sold to Dalhousie University to help finance its own move downtown. Like NSCAD, the AGNS never found this space large enough to serve its needs; almost immediately its curator and founding director, Bernard Riordon (b.1947), began plans to find a permanent home for the AGNS. In 1984 the province’s acquisition of the dilapidated painted house once belonging to Maud Lewis (1901–1970) served as a major spur for the proposal for a new home for the gallery on the Halifax waterfront. The proposed building would feature the restored Maud Lewis House as a central attraction and an anticipated focal point for tourists on the waterfront.

Unfortunately, the land on the waterfront ended up going to a private developer, and an abandoned historical building across the street from the provincial legislature was given to the art gallery. The new Art Gallery of Nova Scotia opened to the public in 1988—ironically, in a building too small to accommodate the Maud Lewis House. In 1997 a Phase Two expansion saw the gallery acquiring two floors and part of the basement of an adjacent building, the Provincial Building, which houses offices for the province; the expansion opened in 1998. The Scotiabank Maud Lewis Gallery, which was supported by the Bank of Nova Scotia and the Craig Foundation, provided a permanent display space of the Maud Lewis House and an exhibition of her work.

Known throughout the 1980s and 1990s as a relatively conservative gallery with a focus on folk art, the AGNS began to change its focus in the late 1990s with the hiring of two contract staff: Peter Dykhuis (b.1956) (seconded from NSCAD’s Anna Leonowens Gallery) as curator of contemporary art, and John Murchie (b.1943) as associate curator. In 2001 the gallery opened its First Nations and Inuit Art Galleries, under the curatorship of Jim Logan (b.1955). Plans for the construction of a satellite gallery in Yarmouth began in 1999, and it officially opened in 2006. In 2001 I was hired as the gallery’s first permanent curator of contemporary art. That was also the year the Sobey family approached the AGNS about organizing a biennial prize for Canadian art. Funded by the Sobey Art Foundation, the Sobey Art Award rapidly became the most coveted art award in Canada. The biennial (and from 2006 annual) award exhibitions meant that the AGNS focused more forcefully on contemporary art, albeit while maintaining a diverse program of historical, folk art, and fine craft exhibitions.

AGNS director Riordon left in 2002 to assume the directorship of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton, New Brunswick. His replacement was Jeffrey Spalding (1951–2019), who had been a former contract curator at the Centennial Art Gallery. Spalding’s focus while at the AGNS was on growing the gallery’s permanent collection, which under his tenure grew by several thousand objects. Spalding also continued the gallery’s efforts to reach diverse communities in Nova Scotia with the hiring of David Woods (b.1959) as part of a short-lived African Nova Scotian Arts initiative. The program did not survive Spalding’s departure in 2007 to head Calgary’s Glenbow Museum.

In 2019 the province of Nova Scotia announced plans to construct a new building for the AGNS on a vacant lot next door to the proposed site from 1984. In 2020 an architectural team was awarded the contract for the building’s design: KPMB Architects with Omar Gandhi Architects, Jordan Bennett Studio, Elder Lorraine Whitman, Public Work, and Transsolar.

1976: Folk Art of Nova Scotia

The Art Gallery of Nova Scotia’s (AGNS) first touring exhibition was Folk Art of Nova Scotia, which opened at the AGNS in 1976 before travelling in 1977 and 1978. The exhibition featured the work of thirty-two artists as well as examples of works by anonymous makers. Although the majority of the artists lived and worked in rural Nova Scotia, Folk Art of Nova Scotia had a huge impact in Halifax. Its success—it introduced the Canadian art world to Maud Lewis (1901–1970), Joe Norris (1924–1996), and Collins Eisenhauer (1898–1979), among other folk artists who went on to acclaim—set the course for the AGNS promoting (some have argued that “creating” might be more accurate) Nova Scotia folk art and artists almost to the exclusion of more contemporary work. The gallery’s interest in folk art was strategic, as folk art was an area that was demonstrably Nova Scotian and that could be marketed both internally and externally to help the AGNS in its desire to create a permanent building for itself.

The artists in Folk Art of Nova Scotia were similar in that they were mostly elderly, mostly little-educated, and mostly rural. Few of them had much schooling beyond elementary, and all of them had worked hard all their lives in working-class occupations. They made their art with no expectation of fame or profit. They worked in relative isolation and obscurity, and few of them even knew that there were other people making the kinds of things they were. There was an element of having mounted this exhibition in the nick of time: of the seventeen living artists in the exhibition, ten were deceased by 1982, and others had stopped making work for health reasons. But there was a growing national and international interest in folk art. The AGNS mounted several other touring exhibitions, including major solo exhibitions of work by Joe Norris and, perhaps most famously, Maud Lewis. “Nova Scotia Folk Art,” unknown as a style before 1976, became the most famous artistic export of the province—a mostly rural phenomenon marketed and disseminated from Halifax.

The 1976 exhibition left a deep imprint on the gallery too. Despite an active exhibition schedule of established Nova Scotia artists, and group shows featuring more emerging artists, it often did seem as if the AGNS was primarily focused on folk art. It wasn’t until 2001 that the gallery would hire its first permanent curator of contemporary art.

1986: “Halifax Sculpture”

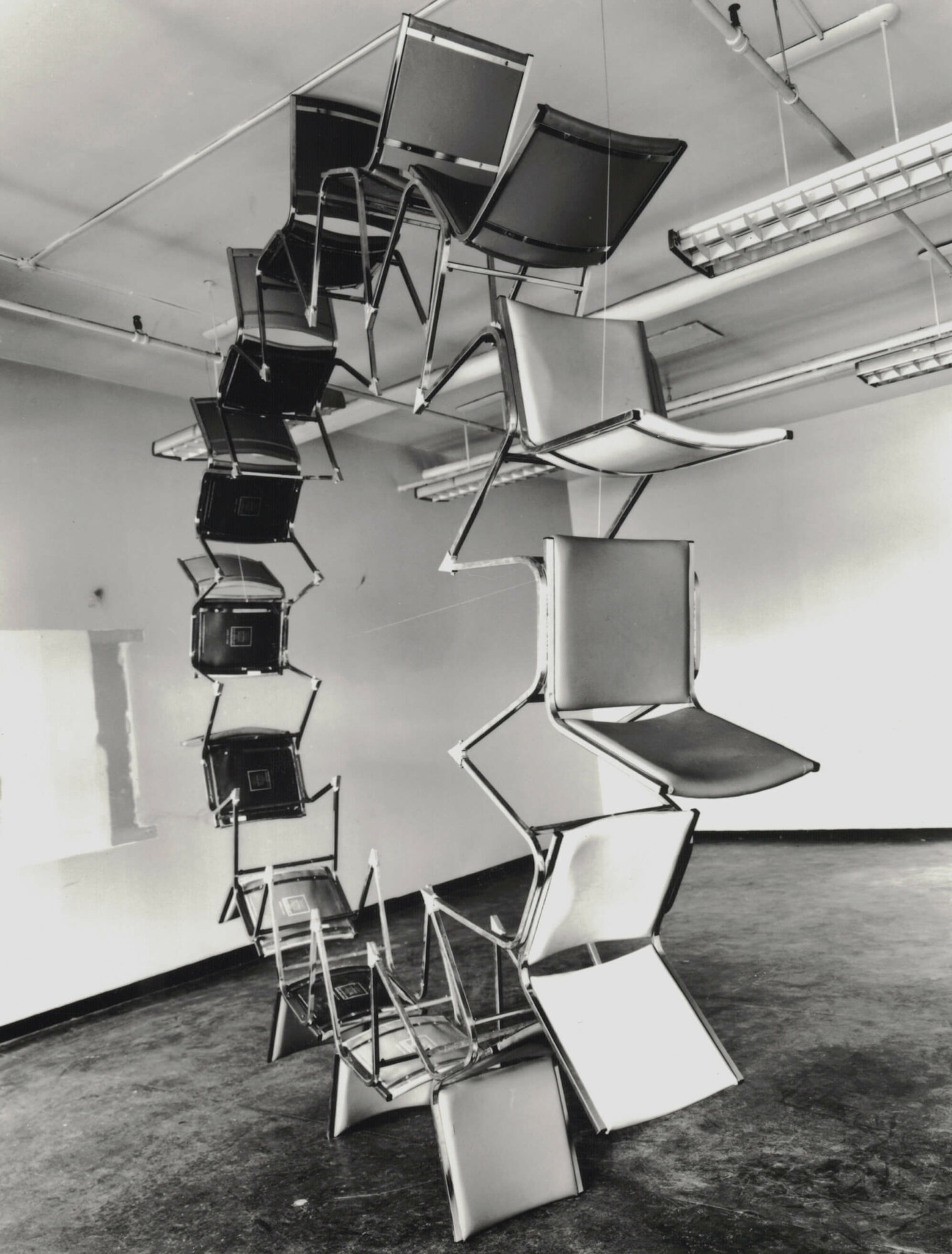

From the mid-1980s until well into the 2000s one of the most dynamic sectors of Halifax visual culture was sculpture. The sculpture phenomenon was fuelled by a generation of artists from the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD) who were part of an international trend of a return to imagery in contemporary sculpture. They were led in part by two senior artists connected to NSCAD, John Greer (b.1944) and Robin Peck (b.1950).

Greer’s 1987 solo exhibition at the Dalhousie Art Gallery, Connected Works, signalled a new, Post-Minimalist approach to sculpture in the city and a way of making objects that relied as much on Conceptual art ideas as it did on a renewed emphasis on materials and traditional techniques such as modelling, carving, and casting. Other artists followed, such as Glen MacKinnon (b.1950), who made large objects carved from plywood, and Thierry Delva (b.1955), who carved in stone and studied as a stone mason to perfect his technical skills after graduating from NSCAD. The 1991 show Critical Mass at the MSVU Art Gallery introduced a new generation of sculptors, such as Greg Forrest (b.1965), Iris Seyler (b.1965), and Philip Grauer (b.1965), who would continue to exhibit regularly throughout the decade. As one curator noted at the time, “contemporary sculpture has established itself in the 1990s in Nova Scotia as an art practice of remarkable vigour.”

Numerous exhibitions in public and university galleries in the period testified to this vigour, but none perhaps more than two artist-led initiatives: The Shed Show in 1993 and Sculpture Expo ’94: The Mall Show in 1994. These two shows followed a series of outdoor sculpture exhibitions on the lawn of the Technical University of Nova Scotia that began in the late 1980s and ran until the early 1990s. Both were held in little-utilized spaces in Halifax (the former immigration shed at Pier 21 and a struggling shopping mall on Spring Garden Road) and were organized by young sculptors.

The Shed Show featured six artists: Shelley Dougherty (1969–2011), Philip Grauer, Bruce MacLean, Lauren Schaffer (b.1968), Iris Seyler, and Mark Whidden (b.1962). The exhibition was the subject of a feature article in C Magazine by Robin Peck, and one work, by Schaffer, was reproduced on the cover of the magazine. Three of the artists in The Shed Show were also included in Sculpture Expo ’94: The Mall Show, organized by Grauer. That exhibition included the work of nineteen emerging and established sculptors (including Peck and Greer), providing a survey of the burgeoning “Halifax Sculpture” scene.

Sculpture’s prominence in the city was acknowledged in 1995 with Object Lessons: Eight Nova Scotia Sculptors, an exhibition at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (AGNS) dedicated to contemporary Nova Scotia sculpture. As curator Robin Metcalfe wrote, “The first half of the 1990s has seen a steady stream of strong younger sculptors coming out of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, while a cluster of mature sculptors associated with the College has gained national and international recognition.” The show was evenly split between four artists representing the NSCAD sculpture tradition—Thierry Delva, Greg Forrest, Kelly Mark, and Philip Grauer—and four who reflected different, more traditional ideas of sculptural practice. The NSCAD sculptors were all graduates of the College, some of them teachers there, and were all to achieve notable success in the coming years (including Grauer’s success as a gallerist—he still runs the commercial gallery Canada in New York.)

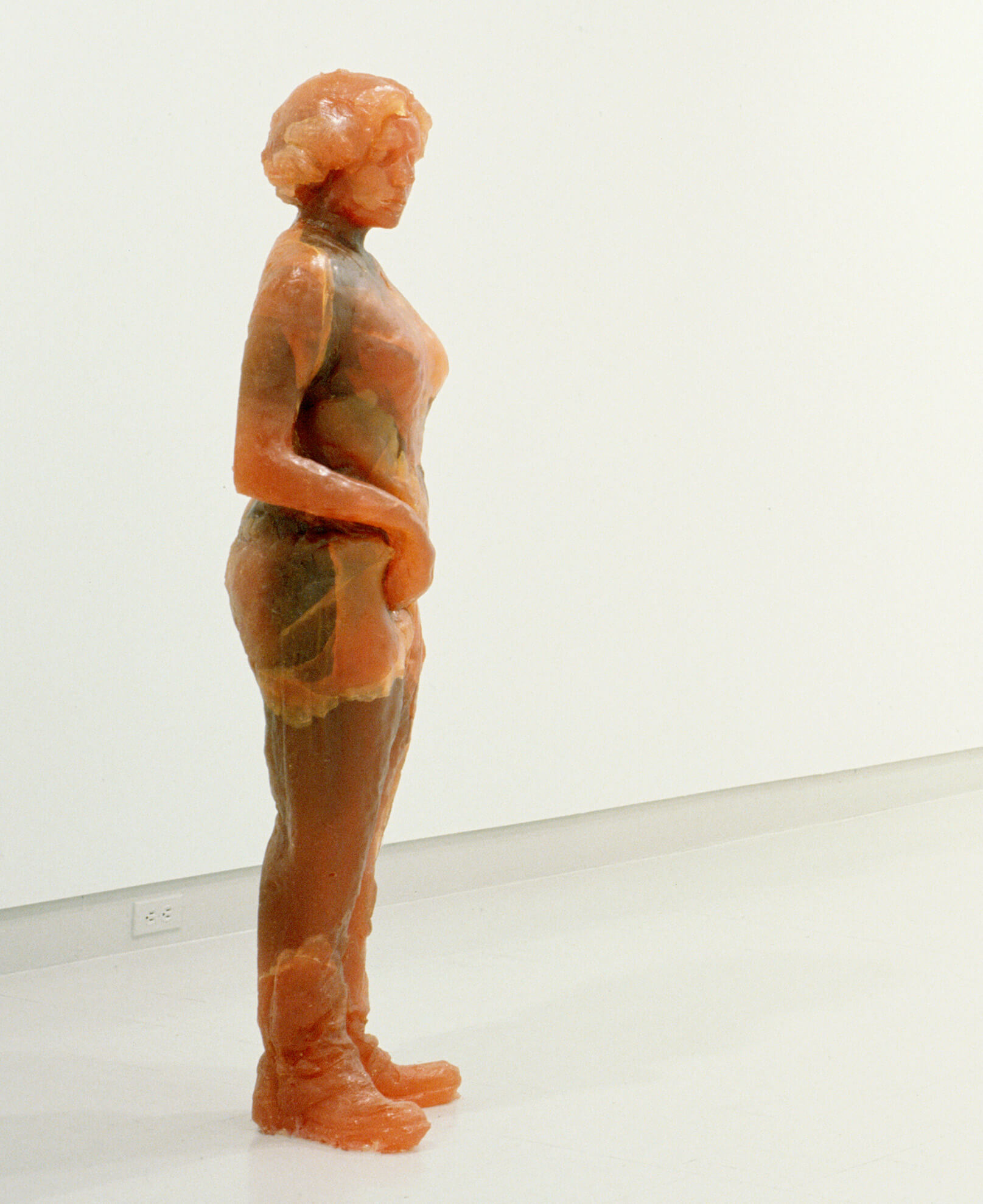

The scene made its Toronto debut in 1996 when Kenneth Hayes curated the exhibition 1:1 Recent Halifax Sculpture for Toronto’s S.L. Simpson Gallery. That exhibition featured the work of Delva, Grauer, and a younger artist from Halifax, Lucy Pullen (b.1971). Her Sucker, 1996, a figure cast in hard candy, is one of the few examples of a life-size self-portrait by any Canadian sculptor (another is Sarah Maloney’s [b.1965] beaded work Skin, 2003–12).

A movement driven by artists, “Halifax Sculpture” quickly became accepted by the institutional art world in the city and beyond. John Greer continued to show internationally from his studio in Pietrasanta, Italy. The first two Atlantic nominees for the Sobey Art Award were Colleen Wolstenholme (b.1963) and Greg Forrest. Wolstenholme’s carved plaster sculptures of prescription pills were shown across Canada and eventually acquired by the AGNS, while Forrest’s large bronze Anything Less is a Compromise, 2004, was included in the nationally touring Arena: The Art of Hockey. Thierry Delva’s work was the subject of a nationally touring exhibition from 2004 to 2005, and his iconic Box Works were acquired by the National Gallery of Canada.

But in the end, the momentum was unsustainable. The 1990s and early 2000s may have been a golden age of sculpture in Halifax, but most of the artists involved have since left the city (several to teach at art schools around the country) and some have stopped making art, though a few continue to work in Halifax. Nonetheless, the “remarkable vigour” of 1990s and early 2000s sculpture in Halifax made its mark—locally, but also nationally, as Halifax sculptors helped change the way sculpture was perceived in Canadian art.

2001: The Sobey Art Award

In the fall of 2001 the newly appointed curator of contemporary art at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (AGNS) was called abruptly into the AGNS’s boardroom, where gallery director Bernard Riordon (b.1947) was waiting, along with Pierre Théberge (1942–2018), then director of the National Gallery of Canada (NGC), and two representatives of the Sobey Art Foundation: Donald R. Sobey (1934–2021) and his niece, Heather Sobey-Connors. The purpose of the meeting was quickly made clear by Théberge. Sobey, then chair of the NGC’s board of governors, wanted to establish a national art award for young artists, one that would feature artists from every region of Canada and that would come with a large cash prize of $50,000. Could the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia handle something like this?

That newly appointed curator was me. Théberge explained that Sobey had brought the idea to the gallery. As the regional approach to the award, in Théberge’s view, fell outside of the NGC’s mandate, he had suggested they take the idea to the AGNS. Could I develop a model for an award, they asked, that would be adjudicated by contemporary curators and have a truly national reach? I said I could, and began planning. The prize, to be awarded biannually, launched in the fall of 2002. The model I developed remains more or less in place to this day: five curators from five regions of Canada (the Atlantic, Quebec, Ontario, the Prairies and the North, and the West Coast), a longlist of five artists from each region, and a short list of one nominee chosen from each. The winner would be selected by the same panel. Initially the jury members all had to be curators at collecting institutions, but that criterion expanded over time due to the need to widen the juror pool.

The first Sobey Art Award exhibition, mounted at the AGNS, featured Brian Jungen (b.1970), David Hoffos (b.1966), Marla Hlady (b.1965), Jean-Pierre Gauthier (b.1965), and Colleen Wolstenholme (b.1963). Jungen was chosen as the winner by a five-person panel made up of Pierre Landry from the Musée d’art contemporain de Montreal, Jessica Bradley from the Art Gallery of Ontario, James Patten from the Winnipeg Art Gallery, Bruce Grenville from the Vancouver Art Gallery, and me, representing the AGNS. I was also chair, and the award was administered initially by the Icelandic Canadian artist Svava Thordis Juliusson (b.1966), now based in Hamilton, Ontario, and later by the Nova Scotia artist Eleanor King (b.1979), now living in New York. When I became acting director of the AGNS, Sarah Fillmore, then the AGNS’s senior curator, became jury chair, fulfilling that role until 2015.

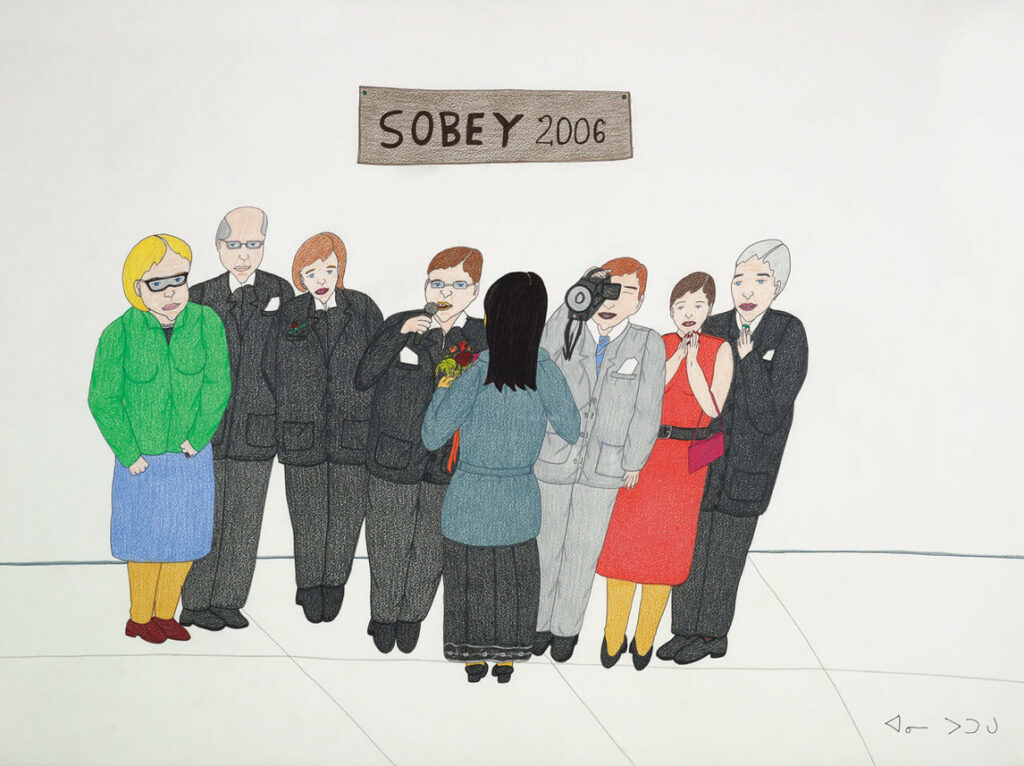

The 2004 award exhibition (won by Jean-Pierre Gauthier) toured Canada through 2006. That year the decision was made to make the award an annual event, and to hold it in Halifax and another Canadian city on alternating years. The 2006 award exhibition was held in Montreal, where the prize went to Annie Pootoogook (1969–2016).

The Sobey Art Award rapidly became the best-known contemporary art prize in Canada. An honour, not to mention a significant cash prize, conferred on important artists across the country, it also brought unprecedented levels of attention to young Halifax artists, who benefited from the exhibitions at home every two years, as well as from the annual visits of the curatorial panel. Numerous young artists, not only in Halifax but across the region, came to the attention of gallerists and curators who may never have seen their work but for the annual longlist of the award that had come to be known simply as “the Sobey.”

From 2002 until 2015 “the Sobey” made Halifax one of the centres of contemporary art in Canada. After my departure from the AGNS in 2015, the award was moved to the National Gallery of Canada in 2016, where it remains to this day. In 2018 the Sobey Art Foundation raised the value of the award to $100,000, and added prizes of $20,000 each for the other artists on the shortlist and of $2,000 each to the remaining twenty artists on the longlist.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements