An award-winning artist whose insights about social justice, colonialism, and the environment were ahead of their time, Jin-me Yoon (b.1960) has created stunning photography, video, and performances that provoke viewers with urgent critique and a vision for better futures. Her creative vision emerged from a childhood that began in rural Korea and took her to a new life in Vancouver, giving her a complex understanding of multiple realities. While she first became known for works that questioned Canadian narratives and challenged anti-Asian histories, her later projects explore global networks and diasporas, demonstrating how colonialism and unrestrained development bankrupt both humanity and the planet. Living and working on the traditional unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations (Vancouver), Yoon produces work that has international relevance and is located within networks that place her alongside discourses in contemporary art, global Asias, global diasporas, and Indigeneity.

Early Life

Jin-me Yoon was born in 1960 in Seoul, Korea. Her parents, Chung Soon Chin (Jewel) and Myung Choong Yoon (Michael), were both born in 1935 and raised in Korea during the 1930s and 1940s, when the country was a Japanese colony. After Japanese rule ended in 1945, Korea was divided into the Soviet-backed North and the American-backed South. Conflict began soon after partition, culminating in the Korean War (1950–53) and military dictatorships.

For Chung Soon and Myung Choong, militarism was never far from their experience, and it shaped their everyday lives. Yoon grappled with this fact in one of her early works, Screens, 1992, which features a class picture of her mother on a school trip to visit an American naval ship. The commemorative photograph was given to Chung Soon and the other students, along with a handful of candies. Recounting this moment, Yoon’s mother ironically commented on this seemingly innocent, yet ideologically loaded gesture, which Yoon featured in her installation: “If a ship is this big and nice, how much nicer can America be! Perhaps I may go there, if only in my dreams??”

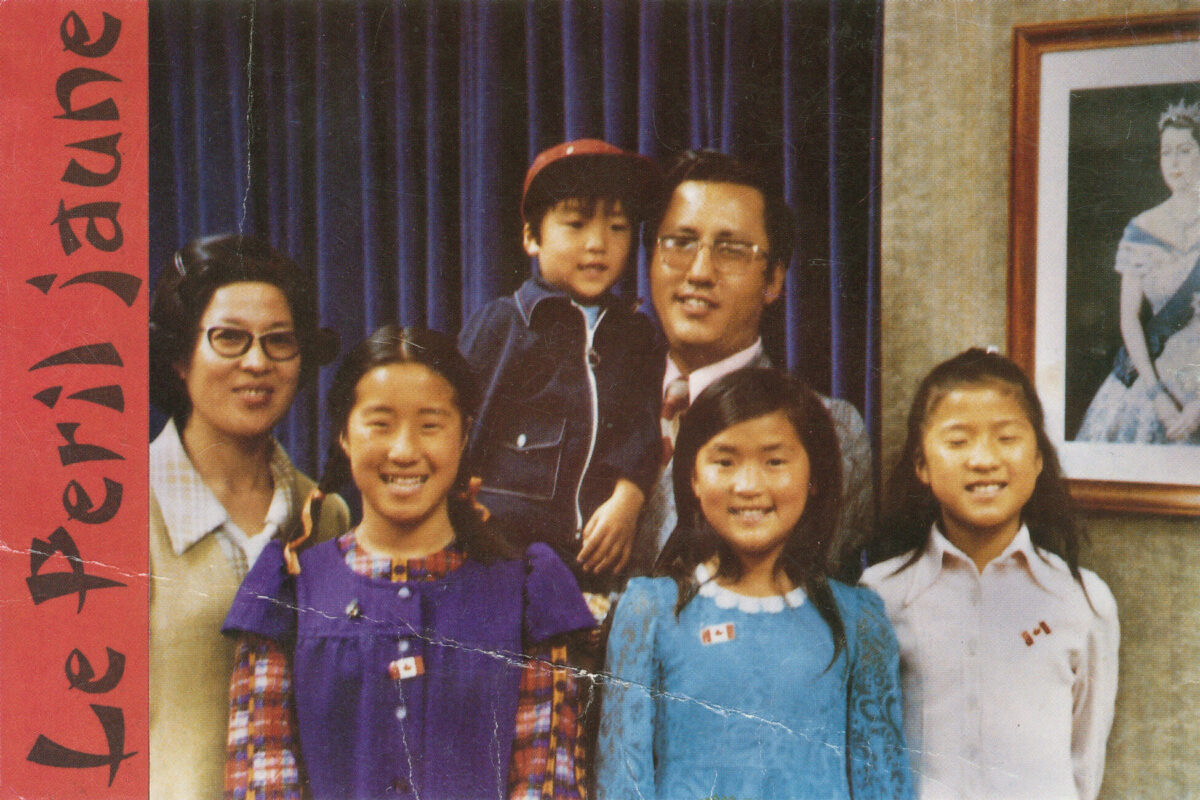

Yoon’s father went to Canada in 1966 to study pathology in Vancouver, and the family followed two years later, after immigration reforms in 1967 sought to end discrimination on the basis of race. Inspired by Canada’s universal health care and wishing to leave behind the imperialist history between the United States and Korea, the Yoon family immigrated to British Columbia, where Myung Choong started his medical practice.

The journey to Canada in 1968 took Yoon and her family on an overnight layover through Tokyo, a visit that exposed her to the fast-paced growth of 1960s Japan. She remembers that her uncle arranged for the family to stay in a high-rise hotel and gifted them an Olympus camera for their new lives in Canada, as photography was important to both Yoon’s uncle and her father.

The contrast with their lives in Korea was striking, as her memories of postwar Seoul are of a landscape of horizontality and a street whose most notable structure was a three-storey building. By contrast, on Yoon’s journey, the views from the airplane and Tokyo itself were pure verticality, shaping her earliest ideas about progress. She recalls looking down on commuters from a high-rise building, seeing “all of the heads from above, moving like ants.” This precipitous shift in perspective re-emerged years later in her exploration of horizontal movements, migration histories, and minoritized subjects in opposition to top-down perspectives, official narratives, and universalizing claims. It can be seen in works such as The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul), 2006, and As It Is Becoming (Seoul), 2008.

Upon arrival in Canada, Yoon began attending school in East Vancouver, where she was given an English name by a family friend: Alina. Photographic images of consumerism, as seen in advertising, were ever-present, a striking contrast with the material culture of Korea, where late capitalism had not yet taken hold.

Yoon was transfixed by the images available in her new environment; her father would bring home glossy magazines such as National Geographic, Reader’s Digest, and luxury publications filled with ads for watches and cruises from the waiting room of his medical practice. From the age of twelve, Yoon would transform these pictures into collages, and she comments that “it was not making images, but receiving images that stimulated my creativity. I was a little semiotician, really! The space of image making was really about the space of images and the work that they did on you.”

In particular, she used collage to create her own worlds, critically engaging with popular culture and tourism through her artworks, which were counternarratives to the mass media representations that she saw in the magazines her father brought home. She comments, “I knew that the world was not as it was portrayed, and that we did not have to accept it…. That [insight] was from the experience of migration.” Moving from rural Korea, where she lived with her grandparents in North Jeolla province, to Seoul, then to Tokyo, and finally to Vancouver, provided Yoon with a collision of cultures, speeds, languages, and values as well as a profound understanding of dislocation—an effect that can be described as contrapuntal. Yoon learned to combine these multiple worlds through the medium of collage, which has persisted in her work in different forms throughout her career.

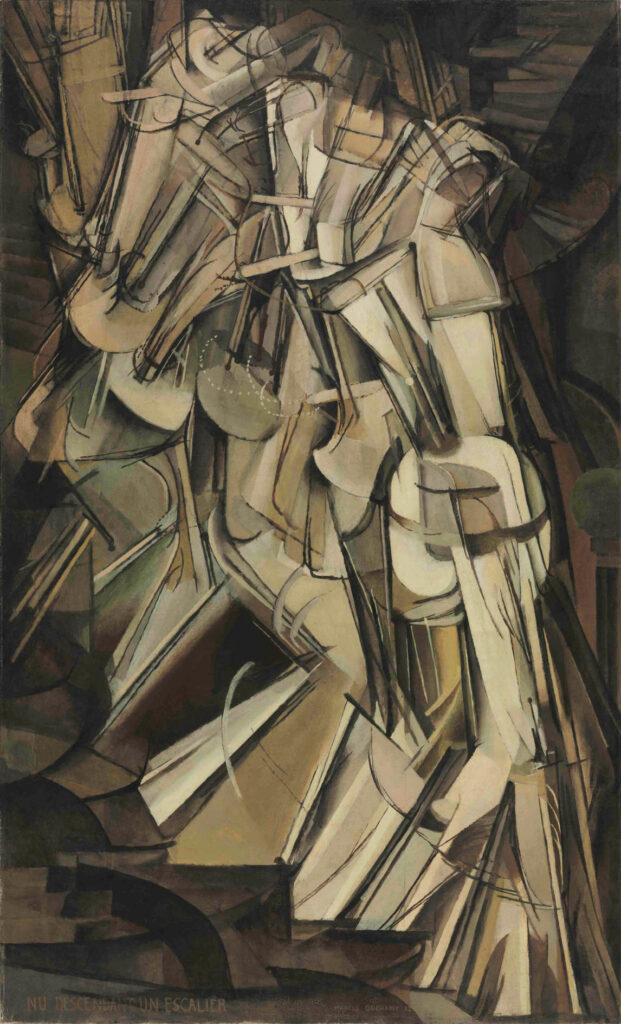

Caught between Korean, hauntings of Japanese, English, and French, Yoon understood language as political, and linked to histories of trauma, loss of language, and migration—a theme that she took up years later in between departure and arrival, 1997. In high school, Yoon discovered the power of gesture and dance, which she added to her already deep engagement with visual culture. Her art historical education consisted of childhood visits to temples in Korea combined with the curiosity that she brought to the Time Life Library of Art that her parents collected, which introduced her to Henri Matisse (1869–1954) and Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968). She had studied ballet as a child, but as a teenager she became aware of modern dance through a high school teacher who introduced her to Martha Graham (1894–1991). It was in art school that the work of Yvonne Rainer (b.1934), Anna Halprin (1920–2021), Simone Forti (b.1935), and Merce Cunningham (1919–2009) helped Yoon to see ordinary movements as dance and first connected her early excitement for dance to visual art. Of particular importance to Yoon’s later work was the interest she took in the ways in which ordinary movements could be full of expression and energy. She became fascinated by the intersection of gesture, performance, and meaning making.

Studies, Travel, and Political Awakening

Yoon entered the University of British Columbia (UBC) in 1978, where she began the Arts One program in the Humanities and was struck by its unthinking Eurocentrism, which constructed white male narratives, creative production, and philosophical writings as universal. “There were no real critical frameworks where I didn’t feel like I had to squeeze into where I didn’t belong,” she said. Thus, although the training that she received at UBC provided her with a foundation of ideas, it was also an experience of alienation that did not address large parts of her intellectual and cultural identity—a deficiency that has informed her research and work.

Time away from school travelling was as important to Yoon’s education as that spent in the classroom. In her third year at UBC she joined the Canada World Youth Program, which sent her to India, opening her perspective on the world and helping her to understand colonialism from yet another point of view as India grappled with its own colonial history. In 1983 she went to South Korea intending to stay for a year, but she continued her travels elsewhere in Asia after seven months. Living in a society entrenched in the Cold War and steeped in its militarized culture, Yoon was constantly reminded of the fragility of the armistice between North and South Korea.

The tension Yoon herself felt made Korea’s difficult histories tangible. Around her, she could see the physical consequences of Japanese colonization (1910–45), the partition of the Korean peninsula between Soviet and American occupation zones after the Japanese surrender (1945–48), and the still unresolved Korean War (1950–53), followed by the militarization of both Koreas. This period was important in solidifying her understanding of Korea’s role as a pawn in global geopolitics, laying the foundations for her later work on colonialism and militarism.

After graduating with a BA in Psychology, Yoon took an art history course, which introduced her to new ways of engaging critically with the world. With little previous artmaking experience, she embarked upon a BFA at Emily Carr College of Art (now Emily Carr University of Art + Design) in Vancouver (1985–90). Yoon recalls the art school environment being stimulating and liberating, with her professor Ian Wallace (b.1943), a pivotal figure in the development of Vancouver photo-conceptualism, organizing a steady stream of interesting artists, intellectuals, and cultural theorists through the Art Now class. Yoon also participated in the Simon Fraser University Visual Art Intensive Art Seminar, where a visit by Mary Kelly (b.1941) and Griselda Pollock (b.1949) in 1989 had an important impact on her work, providing models for thinking about difference and identity through feminist vocabularies and framing motherhood as a subject of artistic inquiry. Within Emily Carr, Yoon was also drawn to progressive feminist professors such as Marian Penner Bancroft (b.1947), Sara Diamond (b.1954), Landon Mackenzie (b.1954), and Sandra Semchuck (b.1948), who helped her to develop a critical approach to this exciting, but largely Eurocentric and masculinist, environment. As a result, Yoon felt empowered to articulate her criticisms, and she began to agitate for a more inclusive curriculum.

In 1987 Yoon moved to New York City temporarily, where she was initiated into two diametrically different art worlds that impacted her development. On the one hand, she witnessed the workings of the New York gallery system, with its skyrocketing prices for established Neo-Expressionist painting by artists such as Julian Schnabel (b.1951) and Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988). On the other hand, Yoon also experienced the world of activist art through the works of the group Act Up, artist Jenny Holzer (b.1950), and others during the AIDS epidemic and the harsh social policies of the Reagan years. These artists, as well as graffiti artists such as Lady Pink (b.1964), inspired her to imagine how her critical engagements with culture could be staged in the public sphere.

Yoon followed her BFA with MFA studies at Montreal’s Concordia University. Professors such as art historians and curators Renée Baert, Jessica Bradley, Penny Cousineau, and Reesa Greenberg and artist Lani Maestro (b.1957) shaped Yoon’s thinking, as did a PhD reading group on postcolonial theory that she attended alongside Saloni Mathur. In the context of the Kanesatake Resistance (Oka Crisis) (1990), the Gulf War (1990–91), and 1980s identity politics, Yoon made deep friendships with people whom she debated and with whom she danced into the night, thinking across communities and learning the “politics of what it meant for us to be together.”

Of particular importance to her thinking was her friendship with artist Arthur Renwick (b.1965) of the Haisla First Nation, with whom she attended both Emily Carr and Concordia. Through Renwick and Gitxsan artist Eric Robertson (b.1959), Yoon met other Indigenous artists and activists, and began to reflect upon her own complex position as an implicated subject—a settler of colour on Indigenous lands. This awareness would later emerge in works such as A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996, and Touring Home From Away, 1998.

Transnational Vancouver 1980s-1990s

Yoon’s early career developed across many different intellectual, artistic, and cultural communities, linked through a transnational network of artists, friends, and colleagues. One important early influence was Others Among Others, an exhibition in which Yoon participated while she was still a student at Emily Carr. It was part of the landmark In Visible Colours: Women of Colour and Third World Women Film/Video Festival and Symposium, 1989, co-organized by Lorraine Chan and Zainub Verjee (b.1956). As Sara Diamond later wrote, it was “one of the most important provocations that brought the discourse around race and gender into Vancouver’s nebula.” Held in November, the five-day event included several screenings of projects by directors based in Canada, including Richard Cardinal: Cry from a Diary of a Métis Child (1986) by Alanis Obomsawin (b.1932); The Displaced View (1988) by Midi Onodera (b.1961); and Black Mother Black Daughter (1989) by Sylvia D. Hamilton (b.1950).

-

Alanis Obomsawin, Richard Cardinal: Cry from a Diary of a Métis Child (video still), 1986

Film, 29:00

National Film Board of Canada, Montreal -

Poster for In Visible Colours: Women of Colour and Third World Women Film/Video Festival and Symposium, 1989

Verjee had moved to Vancouver from London, England, and under her leadership In Visible Colours served as an important link between discourses of race and gender in Vancouver and the Black British Art movement, connecting the distinctive yet understudied anti-colonial and anti-racist art scene in Vancouver to larger national and international contexts. These networks capture the transnational Vancouver in which Yoon thrived and which she helped to build. Grassroots connections linked artists through personal relationships, exhibitions, conferences, and archive projects—ties that were distinct from the slightly later rise of the “global contemporary” facilitated by the types of relationships fostered by biennial art exhibitions and the global art market.

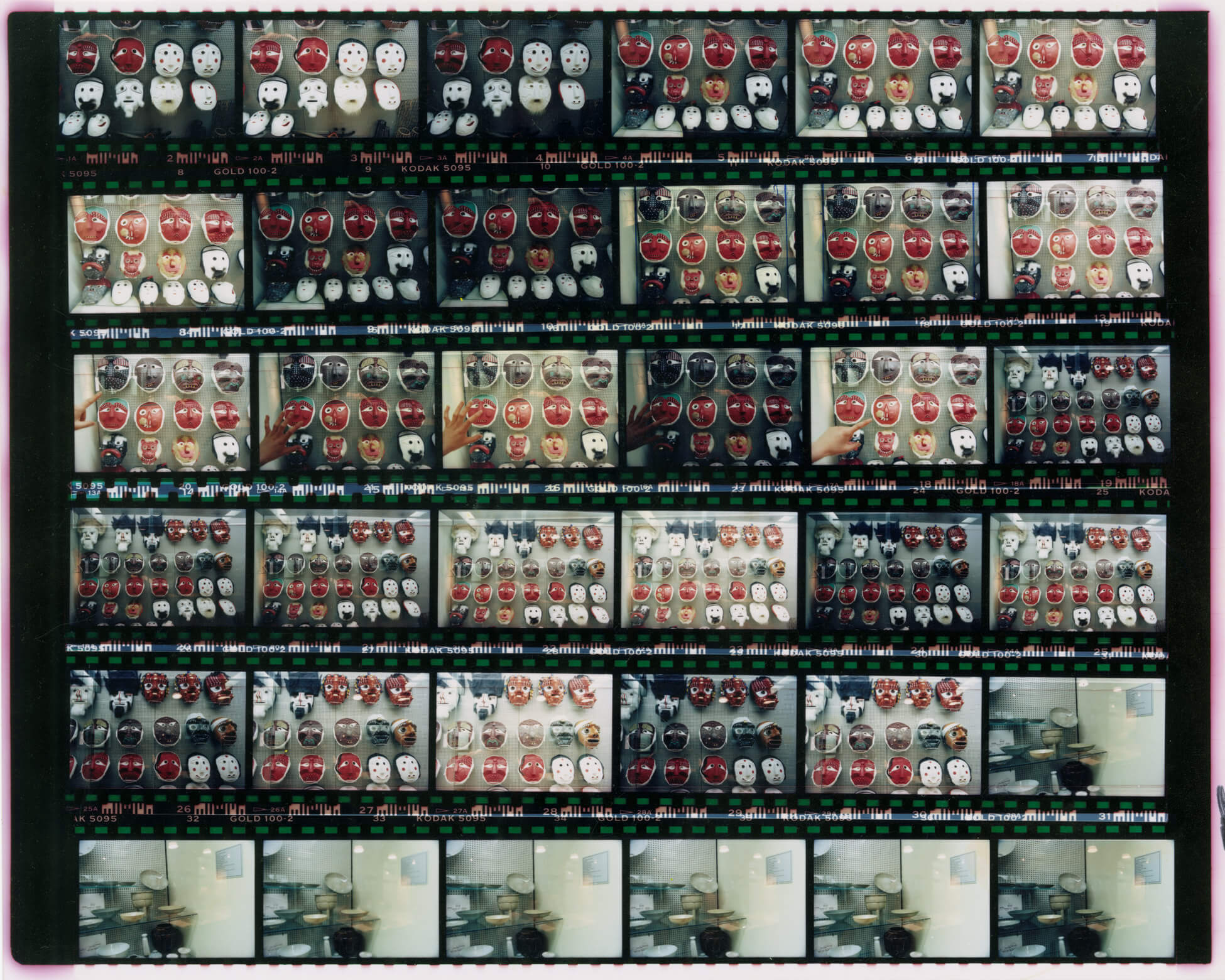

Yoon began to show works such as (In)authentic (Re)search, 1990, in Vancouver galleries, becoming conscious of her role as a Vancouver artist who had been trained within the intellectual contexts of Vancouver photo-conceptualism, yet departing from those models with artwork that “is as much about who is represented as how.” While her focus on systems of representation—a critique that addresses how images are constructed—owes its intellectual rigour to that training, with projects such as Souvenirs of the Self, 1991, her work went further, to engage seriously with form and consider how representation is mobilized to construct identities, histories, and nations. Yoon’s 1989 introduction to Mary Kelly and Griselda Pollock, as well as In Visible Colours, were as significant to her artistic formation in Vancouver as photo-conceptualism.

Upon graduation Yoon was hired by Vancouver’s Simon Fraser University, in the School for the Contemporary Arts, an interdisciplinary department. The classes she taught combined studio and theory, bringing critical perspectives from the Frankfurt School, psychoanalysis, and semiotics into studio classes, and decentring these approaches to address race, gender, sexuality, and Indigeneity.

-

Jin-me Yoon and Susan Edelstein, Questions of Home I, 1994

Benchremarks at Robson and Thurlow, Vancouver Association for Noncommercial Culture fonds

Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, University of British Columbia, Vancouver -

Jin-me Yoon and Susan Edelstein, Questions of Home II, 1994

Benchremarks at Robson and Thurlow, Vancouver Association for Noncommercial Culture fonds

Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, University of British Columbia, Vancouver -

Installation view of Ken Lum’s There is no place like home in 2001

At the Kunsthalle, Vienna

The Vancouver Association for Noncommercial Culture provided an important context for Yoon’s early work, solidifying her own practice as an artist who is also a public intellectual. The group’s focus on creative initiatives to impact the public sphere and its strong, independent, artist-run culture were influential to her practice as she was coming of age as an artist. Yoon contributed to two projects for the association in collaboration with curator and artist Susan Edelstein. Questions of Home I, 1994, was a part of the Benchremarks project, and consisted of a bus bench painted in the red and white stripes of the Canadian flag, forming the background to this conversation: “Where are you from? No, where are you really from?” to which the response, “Really, I’m Canadian” is given, echoing the microaggressions that Canadians of colour endure on a regular basis from strangers. This indictment of “nice” racism, raising awareness of the perspectives of racialized Canadians and starting conversations about belonging in the public sphere, was ahead of its time, alongside, for example, There is no place like home, 2001, by Ken Lum (b.1956).

Yoon soon became a prominent figure in the growing discourse on race, identity, nation, and gender in Canada, alongside other artists and filmmakers working toward social justice such as Dana Claxton (b.1959), Laiwan (b.1961), Melinda Mollineaux (b.1964), Loretta Todd, Henry Tsang (b.1964), and Paul Wong (b.1954) in Vancouver; Jamelie Hassan (b.1948) in London; and Richard Fung (b.1954) and Helen Lee (b.1965) in Toronto. Faye HeavyShield (b.1953) and Laiwan were, and continue to be, important artistic reference points, providing Yoon with models for negotiating politics and aesthetics in their work.

-

LEFT: Faye HeavyShield, Sisters, 1993

Shoes altered with plaster, gesso and acrylic paint, 105 cm (outside diameter installed)

McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg, OntarioRIGHT: Laiwan, African Notes Parts 1 and 2 (detail), 1983/2021

3-channel 149 black and white Panatomic-X 35 mm slide projection

Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, University of British Columbia, Vancouver -

Jamelie Hassan, Meeting Nasser, 1985

Five black and white photographs mounted on Masonite, three VCR videotapes and two laminated sheets, dimensions variable

Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax

Yoon’s art appeared in both Asian Canadian exhibitions in the 1990s as well as shows that addressed the intersection of racial marginalization and Indigenous dispossession. Her work (Inter)reference Part I, (Im)permanent (Re)collection, 1990, was included in the influential Yellow Peril: Reconsidered, 1990–91, curated by Paul Wong, which defined a field of Asian Canadian art in Canada across East Asian communities. Yoon’s projects were also important in establishing solidarity discourses across diasporic and Indigenous communities. Shown in dialogue with artists such as Rebecca Belmore (b.1960), Sarindar Dhaliwal (b.1953), and Sharyn Yuen (b.1956) in Margins of Memory, 1993, curated by Renée Baert, Yoon emerged as an important intersectional artist whose work posed fundamental questions about settler-colonialism, race, and the construction of nation.

Yellow Peril and Margins of Memory formed part of a larger fabric of cultural activities in the 1990s for Asian Canadian artists, and BIPOC artists in Canada more generally, including exhibitions such as Self Not Whole: Cultural Identity and Chinese-Canadian Artists in Vancouver, 1991, curated by Henry Tsang and Racy Sexy: Race, Culture and Sexuality, 1993, curated by Karin Lee and Tsang; the foundation of Minquon Panchayat, a national coalition of racialized artists that formed in 1992; and conferences such as Writing Thru Race, 1994.

Yoon was situated within these conversations on identity politics in Canada and also in the United States and Britain, becoming a part of the growing grassroots networks that linked larger Third World and diasporic discourses. This wider field of solidarity practices emerged as a repositioning of the presentation of the “global” as spectacle for North Atlantic audiences in exhibitions such as Magiciens de la Terre, 1989, at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, a show that was global in scope, but primitivised Asian, African, and Latin American artists as exotic “magicians.” Of particular importance to these transnational anti-colonial and anti-racist discourses were exhibitions such as The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s, 1989, and the 1993 Whitney Biennial in New York, and, in the UK, The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Postwar Britain, 1989.

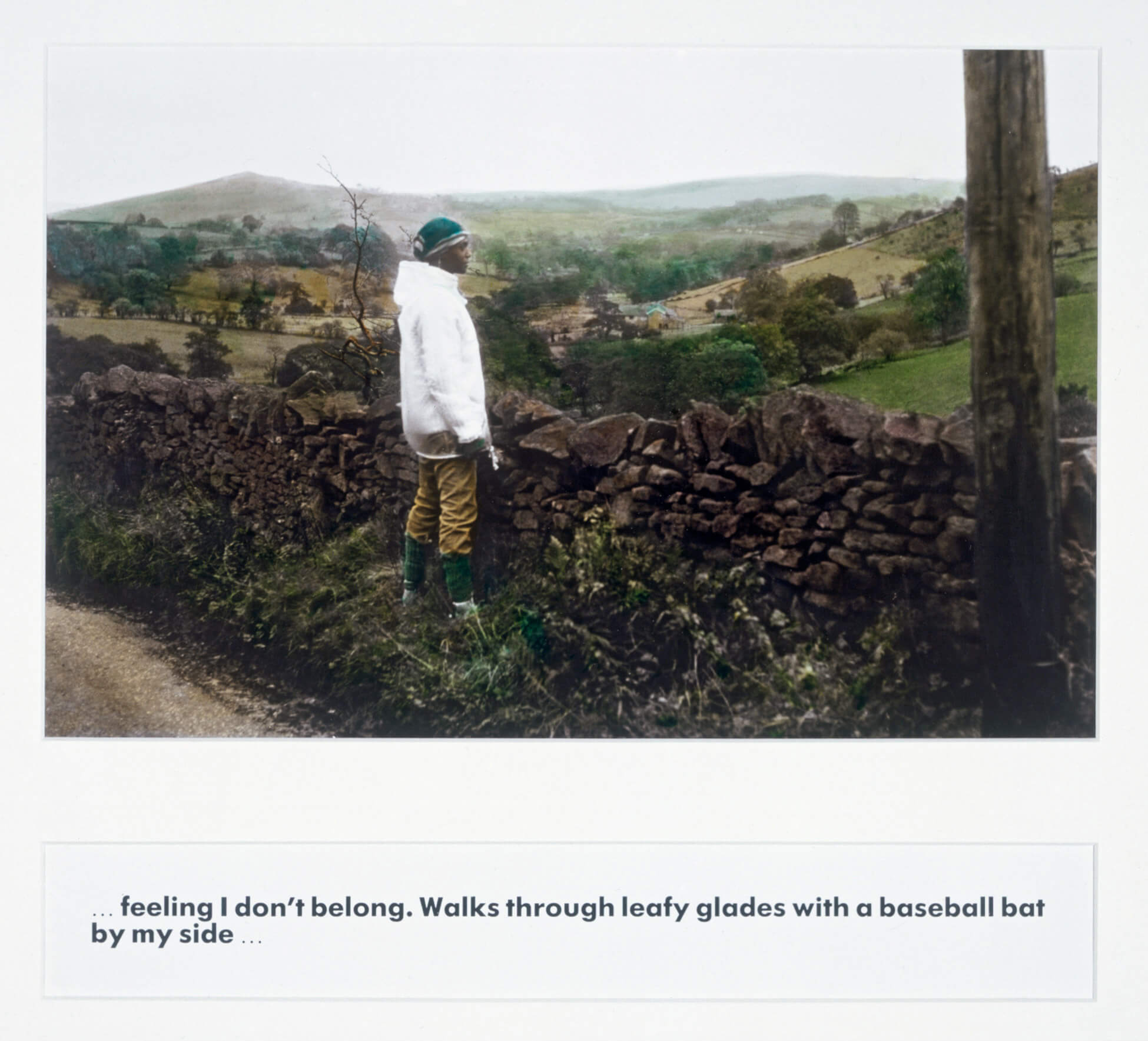

Yoon created her own imagined community on her bookshelves, which she filled with publications and photocopies handed to her by other artists from sources such as the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, the legendary theoretical journal Third Text, and the British photography magazine Ten.8. She actively engaged with and addressed this community, making work (such as Souvenirs of the Self) that was in dialogue with Black British artist Ingrid Pollard (b.1953), whose work she saw in Ten.8, and Indigenous artist James Luna (1950–2018), whose letters—filled with catalogues, flyers, and found objects—Yoon still discusses with enthusiasm. In particular, Luna’s Artifact Piece, 1987/90, was an important impetus for her thinking about museums as a site of representation and identity formation.

Becoming known for her work questioning cultural identity and nationhood, she was invited to a conference in Barcelona in 1993, American Visions: Artistic and Cultural Identity in the Western Hemisphere, where she considered the question “what does it mean to be an American?” alongside artists such as Gerald McMaster (b.1953) and Coco Fusco (b.1960). In 1999, she fully took her place as artist in these transnational anti-colonial and anti-racist networks when her work was included in the international touring exhibition New Republics: Contemporary Art from Australia, Canada, and South Africa, 1999, co-curated by Indian-Canadian-British photographer Sunil Gupta (b.1953) and Australian curators Edward Ward and Clare Williamson.

Asian Trajectories

By the early 1990s, Yoon was beginning to garner international attention, particularly through exhibitions expanding the field of contemporary Korean art. In 1993 she was invited to show her work Screens, 1992, in Across the Pacific: Contemporary Korean and Korean-American Art at the Queens Museum of Art in New York (now the Queens Museum) and the Kumho Museum in Seoul. Curated by Jane Farver, Minne Jungmin Hong, Elaine Kim, and Lee Youngchul, the show connected her to the Korean and Korean diasporic art worlds, giving her work a larger transnational context in which to resonate. She continued to develop this important network of artistic and professional relationships throughout her career.

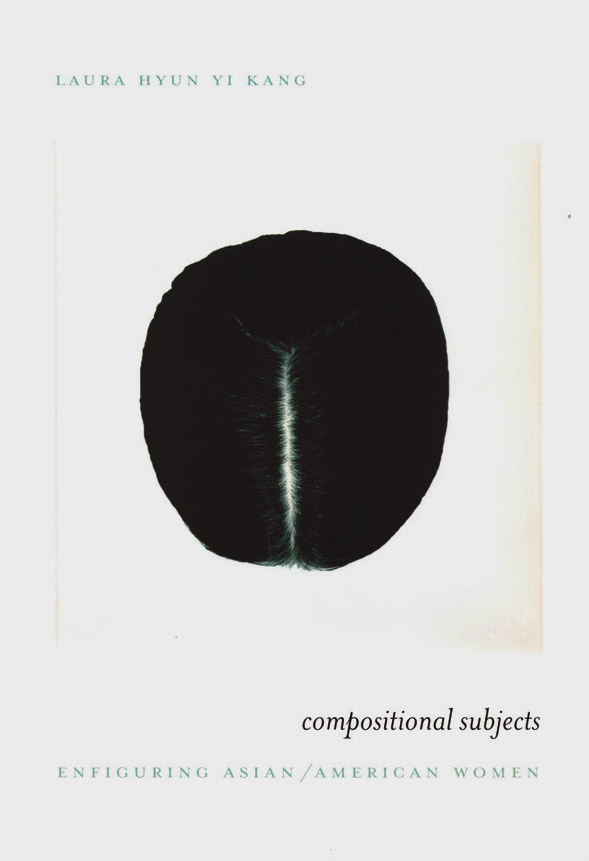

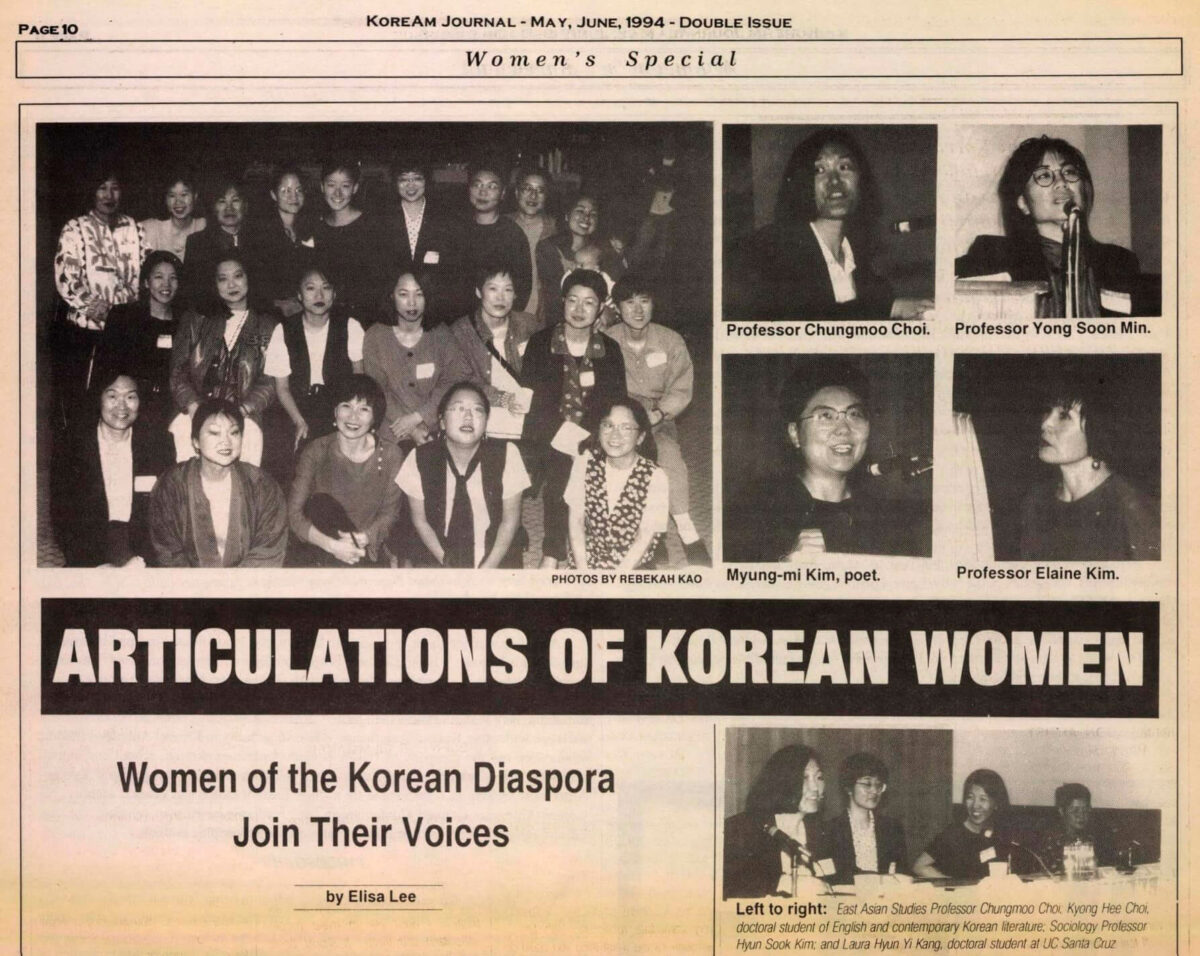

This sense of a globally dispersed community of the Korean diaspora was reinforced in 1994, when Yoon was invited to speak at Articulations of Korean Women, a conference at the University of California, Berkeley co-organized by the Center for Korean Studies and the Asian American Studies department, continuing her dialogue with scholar and curator Elaine Kim, and introducing her to curator Eungie Joo and artist Yong Soon Min (b.1953). It was an event intended to build community—in Kim’s words, an opportunity to “explore together questions of history, identity and representation” and “celebrate Korean North American women with the experience of turning the world upside down.” Through this gathering, Yoon met other women from the Korean diaspora, such as poet Myung Mi Kim, scholar Chungmoo Choi, and Laura Hyun Yi Kang, who featured between departure and arrival, 1997, Yoon’s first video installation, on the front cover of her book Compositional Subjects: Enfiguring Asian/American Women (2002).

Soon after, Yoon’s work also began to be shown in Japan, with her first exhibition at the Yokohama Citizens’ Gallery, in the show Artists Today: Asia-Pacific Universe: Contemporary Art from Australia, Canada, China, India, Japan, and the Philippines, 1995. There, Yoon connected with other artists and curators from Asia and its diasporas such as Yoshiko Shimada (b.1959), who would form part of her artistic and intellectual world. Reflecting on the deep bonds forged through these networks, Shimada notes, “We don’t meet often, but I consider her as my soul sister.”

Yoon also attracted critical attention from art historians such as feminist powerhouse Kim Hong-Hee. She wrote about Yoon’s work in relation to that of Korean diasporic artists Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951–1982) and Yong Soon Min, contributing to Yoon being perceived primarily as a feminist artist in Korea. In this context, Yoon was framed as part of a first generation of Korean diasporic artists who rose to international prominence. Their concerns with postcolonial issues, gender, identity, language, and migration were at the forefront of critically engaged contemporary art in Korea, and they became a focal point for a Korean art scene committed to exploring global issues.

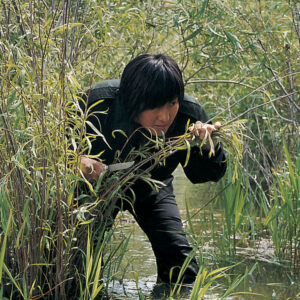

In 2006, Kim Hong-hee invited Yoon to do a six-week residency at Ssamzie Space in Seoul, one of the first alternative spaces in Korea, where she was the founding director. This was Yoon’s first extended stay in Korea since 1984, and it ushered in a new phase in her art that moved beyond racialization and identity and into an engagement with migration and transnational histories. The residency catalyzed the works in the second half of her career, including lateral crawling performances that explore the relationship between colonialism and modernity, such as The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul), 2006, and As It Is Becoming (Seoul), 2008, and recent projects that analyze the consequences of colonialism’s extractive logics through the Anthropocene Era, such as Other Hauntings (Dance) and Other Hauntings (Song), 2016, and Testing Ground, 2019.

Life Cycles

Yoon’s art has always featured her own body and the bodies of her intimates—her parents, her husband David, her children, and her friends. She integrated family photographs into her early works (Inter)reference Part I, (Im)permanent (Re)collection, 1990, and Screens, 1992, and family members were among the participants in A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996, and Touring Home From Away, 1998. Her viewers have seen her children grow up, and her parents, who lived with her in an intergenerational household, age. These slivers of autobiography entangle with Yoon’s critical practice and performative stagings, giving her work an emotional register that warms its intellectual rigour. Balancing on a razor’s edge between fiction and documentary, she both critiques current representational frameworks and proposes more hopeful ways of living and being. The births of her children Hanum in 1994 and Kihan in 1997 prompted Intersection, 1996–2001, a series of works that reflect on the subject of motherhood.

The Intersection series also connects to Yoon’s feminist commitments, forged in dialogue with Mary Kelly (whom she met in Vancouver in 1989) and artist Elizabeth Mackenzie (b.1955), at a time when women’s artistic production and biological reproduction were still not completely naturalized as being compatible. More recently, in works such as Long View, 2017, Yoon turns once again to life cycles and her family, in particular to her adult children and her parents in their twilight years. Works featuring her father took on additional poignance when she displayed his sequence from Turn, 2019, at his funeral, transforming artwork into memorial.

Yoon’s understanding of life’s fragility and the interconnection of generations has in recent years provoked a reckoning with our place as beings on planet Earth. After initially going to Hornby Island on an art school field trip in 1985, Yoon started visiting with her family. Attracted by its bohemian art community and their experiments in living lightly on the land, she forged a deep connection to this place.

Friends from the community appear in works such as Living Time, 2019, which features artists Wayne and Anne Ngan, as well as Tina and Wayne Wai. She writes of the deep sense of rootedness and belonging that she feels on Hornby in relation to her hosts—the K’ómoks First Nation and the natural environment itself: “No small thing to feel emplaced as an immigrant, especially as rural places in Canada are largely inscribed by whiteness as the centre…. But from a different foundational base, privileging Indigenous people leads to an entirely different set of preoccupations about the future and our place in it, focussed on an intermingling with other humans and non-humans that is temporally expansive, based on respect, reciprocity and restraint.”

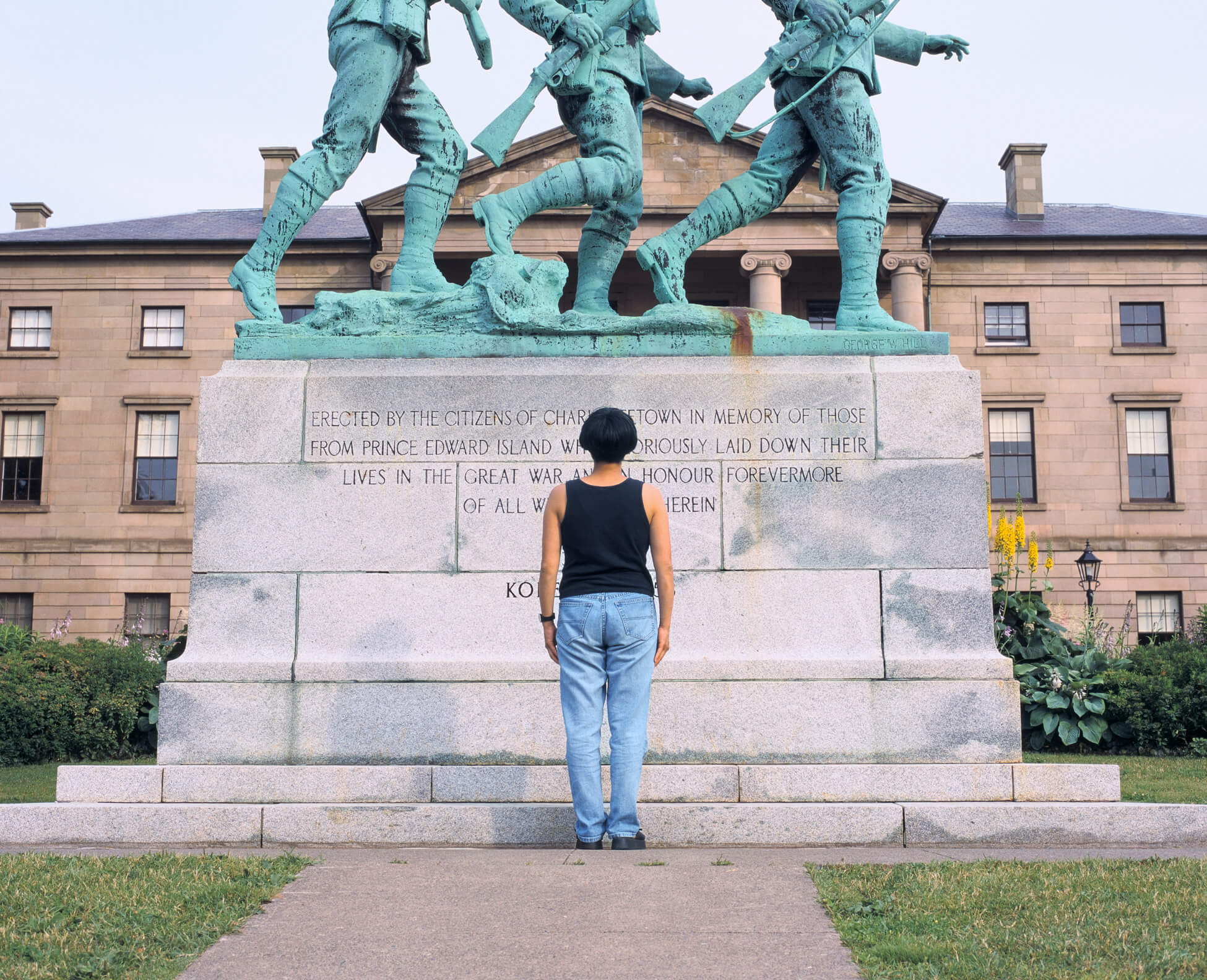

Recognition

Yoon’s early works (1991–2002) have become touchstones in the articulation of Canadian identity and race, entering into the public imagination through exhibitions, collections, and academic studies. Souvenirs of the Self, 1991, is in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada, and A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996, is held by the Vancouver Art Gallery and Library and Archives Canada, intended for the Portrait Gallery of Canada. Both have featured prominently in national and international exhibitions. Within Canada, these projects often function as question marks that provoke reflection on Canadian identity. Within other settler-colonial contexts, such as Australia or South Africa, they provide a vocabulary for connecting anti-colonial and anti-racist art worlds. Within Asia, Yoon’s art complicated notions of Asian identity, providing an intersectional exploration of Asian art with Asian diasporas in what has now come to be known as “global Asias.”

Yoon’s mid-career works (2003–15) have received significant attention, although the complexity of projects such as This Time Being, 2013, have made them purposely less available as consumable icons than her earlier artworks. They were often misunderstood as being about multiculturalism and a desire for inclusion in national narratives. In contrast to this conventional assumption, Yoon’s later artworks, such as Fugitive (Unbidden), 2003–4, provoke viewers to engage and think deeply about the much larger questions she is raising. As explorations of the ways in which history and trauma are carried by the body intergenerationally through time and space, they have been the subject of challenging and high-profile exhibitions.

In 2004, Susan Edelstein curated the solo show Unbidden at the Kamloops Art Gallery, which also travelled to the National Gallery of Canada’s Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography. It was followed by another prominent solo exhibition at the Centre culturel canadien in Paris, Passages through Phantasmagoria, in 2008, with a parallel exhibition, As it is Becoming, at Catriona Jeffries Gallery in Vancouver. Writing in Canadian Art, reviewer Charlene K. Lau captured the importance of the show in bringing Canadian perspectives on race and migration to Europe: “It seems Paris would need this kind of challenging identity-based work more in its public spaces.”

More recently, in the context of Yoon’s later work, such as Untunnelling Vision, 2020, which explicitly engages with her positionality as a guest on Indigenous land, her lateral crawling works like The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul), 2006, are being re-read by Indigenous scholars such as Dylan Robinson as acts of resistance to colonial infrastructures and “reparative perception” by “return[ing] her body into relationship with place.”

-

Jin-me Yoon, Installation view of Turning Time (Pacific Flyways), 2022

18-channel video installation, dimensions variable, varied durations: 9:33 to 15:23, in the exhibition Jin-me Yoon: About Time at the Vancouver Art Gallery, 2022, photograph by Ian Lefebvre -

Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival award ceremony for Jin-me Yoon, 2022

-

Edward Burtynsky and Jin-me Yoon at the Scotiabank Photography Award, 2022

As the complexity of Yoon’s work unfolded, her stature as a forerunner in her field began to be acknowledged with career honours. In 2017, Yoon was commissioned to make Long View for Landmarks/Repères, a program created for Canada’s sesquicentennial. In 2018, she was inducted as a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. From 2019 to 2022, she was the subject of a two-part touring survey, Living Time from Away and Here Elsewhere Other Hauntings, curated by Anne-Marie St-Jean Aubre at the Musée d’art de Joliette in Quebec, which was shown in seven sites across Canada, including an online presentation at the Carleton University Art Gallery.

In 2020, Yoon showed Untunnelling Vision at Truck Contemporary Art in Calgary as a part of the Mountain Standard Time Performative Art Biennial. Two years later, she was granted a solo exhibition of recent works at the Vancouver Art Gallery, About Time. As well, her work was featured in Asia Forum at the Venice Biennale, and she received the prestigious Scotiabank Photography Award, Canada’s highest honour for photography.

Yoon’s newest works, Untunnelling Vision, 2020, and Mul Maeum, 2022, display the maturity of an artist who has long reflected on what it means to be human in the context of great inhumanity and planetary environmental crisis; who understands the histories that individuals carry within them; and who sees the importance of future-focused proposals articulated in hope for generations to come. Mobilizing her parallel research on settler-colonialism in Canada and colonialism in Korea to better understand the ways in which extractive logics have led our society to the current planetary crisis, Yoon explores ways of thinking multidirectionally about repairing the past and defining shared futures.

In 2015, after spending nine years unearthing haunted stories close to the ground in lateral crawling works, Yoon began to seek ways of building futures, asking, “How do we move forward from current conditions in the context of inherited histories of colonialism?” The first project to emerge from this inquiry was Untunnelling Vision, 2020, a work that highlighted Indigenous-immigrant relations through community-based conversations and workshops.

Yoon’s current and future projects, Mul Maeum, 2022, Pacific Flyways, and Listening Place, continue this inquiry, working toward the creation of a place for Indigenous-immigrant relations that respects Indigenous land rights and generates the conditions for the co-creation of a world that does not replicate oppressive structures, but is instead premised upon reciprocity and respect.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements