Jin-me Yoon’s conceptually driven projects interrogate issues of social, historical, and planetary importance filtered through the lens of migration. Her early works were foundational in establishing an artistic critique of race, representation, and settler-colonialism in Canada during the 1990s. Her later projects employ video and photography in a socially engaged practice, and advocate for a structural critique of colonialism and the extraction of territory, labour, and resources from the land and its people. Within Canada and internationally, Yoon’s art has been ahead of its time in exploring these issues.

Examining Nation

-

Jin-me Yoon, A Group of Sixty-Seven (detail), 1996

Two grids of 67 framed chromogenic prints for a total of 134 prints and 1 name panel, 47.5 x 60.5 cm each

Vancouver Art Gallery and Portrait Gallery of Canada/Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa -

Jin-me Yoon, A Group of Sixty-Seven (detail), 1996

Two grids of 67 framed chromogenic prints for a total of 134 prints and 1 name panel, 47.5 x 60.5 cm each

Vancouver Art Gallery and Portrait Gallery of Canada/Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

Jin-me Yoon’s art has been at the forefront of conceptual practices that connect intersectional issues of social and environmental justice through a critique of colonialism and an exploration of migration. Early works such as Souvenirs of the Self, 1991, A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996, and Touring Home From Away, 1998, established Yoon as a leading voice interrogating questions of race, gender, identity, and nation through their dispassionate examination of Canada’s founding mythologies. In other words, her work demonstrated the ways in which museums, landscape painting, and the tourist industry shaped the public imagination of who and what is Canadian, creating a vision of Canada that erased the presence of Indigenous peoples and categorized people of colour as foreign. These important projects were foundational in creating a more complex visual language of Canada and challenging settler-colonialism and the idea that the nation was built upon terra nullius or empty land. This clear and eloquent vision of Canada has been repeatedly featured in prominent exhibitions, both nationally and internationally. Notably, A Group of Sixty-Seven was a conceptual hinge for curator Diana Nemiroff’s exhibition Crossings, 1998, at the National Gallery of Canada, which argued for embodied global perspectives rooted in Canada’s rich migration histories.

Globally, Yoon’s work has provided a visual vocabulary for eloquently cross-examining national mythologies by fracturing the idea that nation and ethnicity are the same. She was featured prominently in Vasif Kortun’s Third Istanbul Biennial, Production of Cultural Difference, 1992, as well as in The New Republics: Contemporary Art from Australia, Canada, and South Africa, 2000–1, which was curated by Sunil Gupta (b.1953), Edward Ward, and Clare Williamson and toured internationally. On that occasion, she exhibited Regard, 1999, a sculpture that positions two of the photographs from A Group of Sixty-Seven—specifically those depicting Yoon and her mother—facing each other. In the show, the significance of Yoon’s work to the anti-colonial art worlds of Australian and South African artistic discourses became apparent, as did her engagement with the British Black Arts movement.

Yoon’s early work also received significant attention in Asia, where it was shown to highlight connections between Asian and North American artistic practices. With its explicit foregrounding of language, history, and migration, Yoon’s art enabled Asian audiences to imagine the cultural presence of Asians in diaspora in exhibitions such as Across the Pacific: Contemporary Korean and Korean-American Art, 1993, at the Kumho Museum of Art in Seoul and the Queens Museum of Art in New York (now the Queens Museum). More recently, Souvenirs of the Self (Lake Louise) featured as the signature image for the National Gallery of Canada’s 2017 sesquicentennial exhibition Photography in Canada 1960–2000.

Art for an Interdisciplinary World

Yoon’s art has garnered serious scholarly attention from a range of different disciplines, including art history, Asian studies, literary studies, geography, sound studies, and visual culture. Although the critical reception and exhibition of her visionary mid-career and later projects have been slow to catch up with the importance of the work, both have been gaining momentum in recent years.

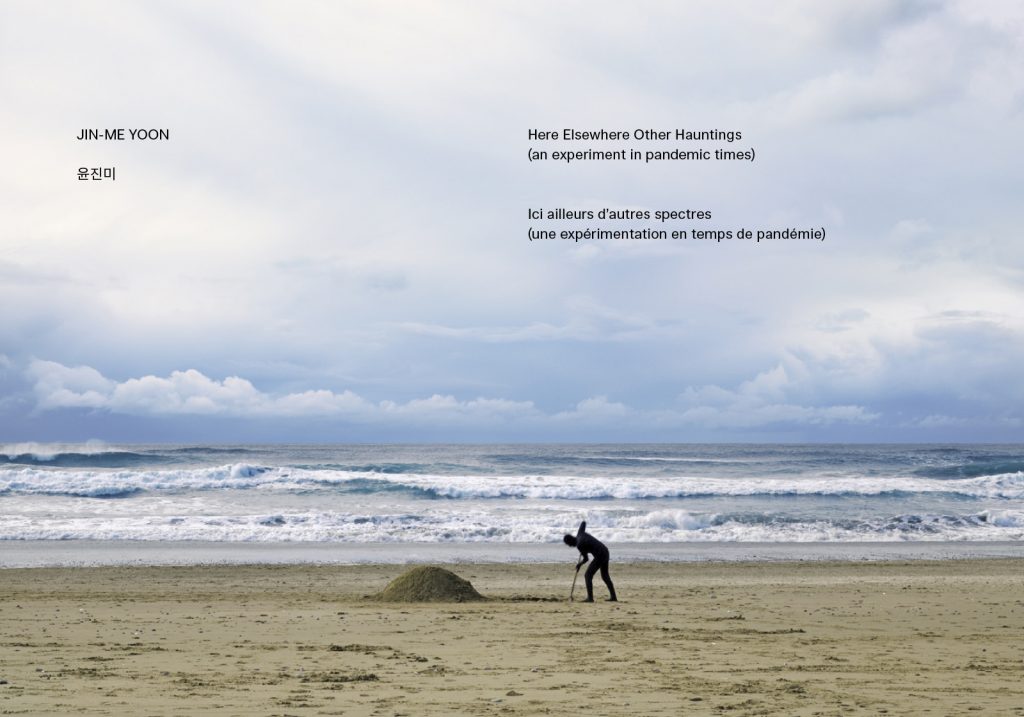

As discourses seeking to define new human relationships with the environment beyond colonial logics of resource extraction gained prominence through the writings of theorists such as Karen Barad, Édouard Glissant, and Sylvia Wynter, Yoon’s prescience and significance came into clearer view. In 2019, she received her first career survey, Here Elsewhere Other Hauntings (an exhibition that went on to tour until 2022), and the following year she showed Untunnelling Vision at Truck Contemporary Art in Calgary as a part of the Mountain Standard Time Performative Art Festival. In 2022, Yoon’s inclusion in Asia Forum at the Venice Biennale, her one-person show About Time at the Vancouver Art Gallery, and her receipt of the Scotiabank Photography Award, Canada’s highest honour for photography, signified the reception that critics and curators have come to give her challenging and important oeuvre.

Bodies, Identities, Memories

Yoon’s art is concerned with the question of how bodies carry perceptions, stereotypes, and histories. While her earliest work, such as Souvenirs of the Self, 1991, is focused on perceptions of race and representations of settler-colonial nationhood, it is also intersectional, addressing both race and gender simultaneously and later, in the Intersection series, 1996–2001, the maternal body. From 2003 onwards, Yoon built upon her early explorations of race and gender, interrogating the body as a site of memory, as she does in Fugitive (Unbidden), 2003–4. In other words, in Yoon’s oeuvre, the body goes from being a racialized and gendered cipher, onto which the viewer projects their own meaning, to being a site of experience that holds intergenerational histories of trauma and migration. As well, Yoon addresses the possibility of working relationally to enable the solidarity needed for healing to take place.

In works such as Souvenirs of the Self, and A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996, Yoon uses the visual vocabularies of tourist snapshots (Souvenirs of the Self) and of passport and ethnographic photography (A Group of Sixty-Seven) to show how racialized bodies are portrayed as not belonging in the Canadian context. Souvenirs of the Self, for instance, plays on depictions of Canada staged for the tourist industry, which in the 1990s assumed a white-settler-colonial national identity. Yet these images are not about wanting to belong but are rather a critique of the terms of inclusion, revealing the narrative structures that are used to construct Canadian identity and state a claim to Indigenous territories that in many cases remain unceded (including in British Columbia, Yoon’s home province).

In this respect, Yoon’s early work is a consideration of the racialization of bodies, and it resonates with that of artists engaged in identity politics such as Laiwan (b.1961), Ken Lum (b.1956), and Paul Wong (b.1954) in Canada; James Luna (1950–2018) and Coco Fusco (b.1960) in the United States; and Ingrid Pollard (b.1953) in the United Kingdom. Like Laiwan, Fusco, and Pollard, Yoon also addresses the intersectionality of racialized and gendered bodies—she is the most prominent racialized woman artist of her generation to do so in Canada. Thus, Yoon’s early projects—which have been featured in many national exhibitions—played an important role in shaping discourses about race and representation for racialized and Indigenous artists such as Camille Turner (b.1960) and Rosalie Favell (b.1958), whose artistic practices interrogate the spaces of beauty pageants and museums.

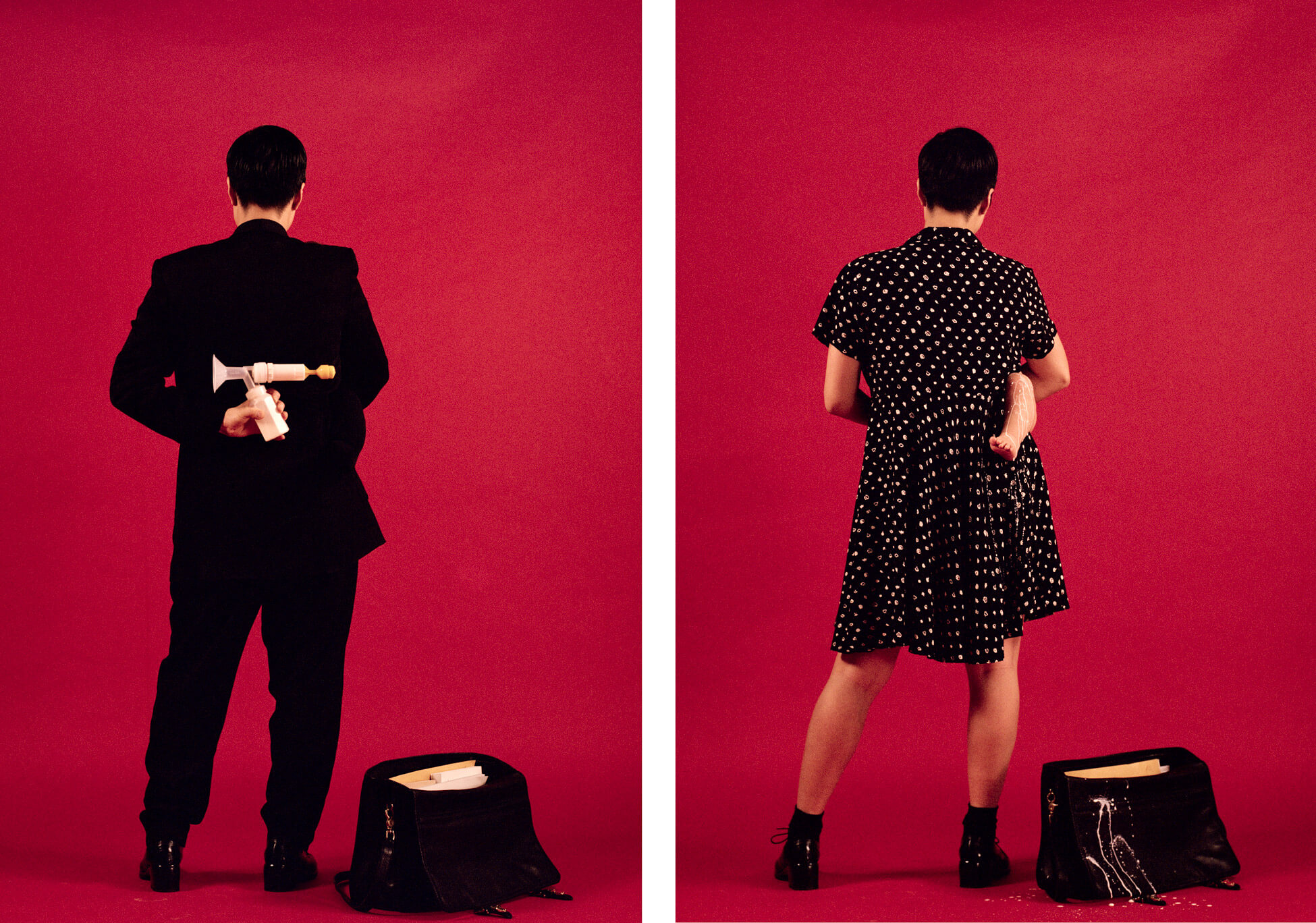

The Intersection series is Yoon’s most overtly feminist work. Using theatricality, artifice, and scale that refer directly to Vancouver photo-conceptualism (a carefully controlled pictorial environment and allusions to both art history and advertising), the photographs in this series launch a pointed critique at the movement’s masculinist claims to universalism and its lack of discursive space for racialized and gendered artists who were excluded from the movement. Yoon asserts the maternal, feminine, and racialized body almost aggressively, in one image spitting out milk while holding the controls for a slide projector or camera shutter release. This gesture reclaims the agency of the female subject in response to Picture for Women, 1979, by Jeff Wall (b.1946), where the shutter release is controlled by the male figure in the photograph—because here, Yoon is presenting a picture by a (racialized) woman.

Mid-career, Yoon continued to develop her critique of photo-conceptualism with works that reject its concern with the gaze, or visual mastery. For instance, in The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul), 2006, she moves her body and her point of view from a vertical to a horizontal axis, gliding along the ground with her abdomen on a wheeled platform. This pivot enacts a critical mind-body shift from the surveying mind-eye (visual mastery) to the sensing body. Similarly, in As It Is Becoming (Seoul), 2008, Yoon swivels not only her own experiencing body, but also those of the viewers, who must adjust their own positions in order to view the work, which is installed upside down and on the floor.

Rather than critiquing the gaze, in this series of works Yoon renders it incidental by giving up the practice of staging her images. Crawling on the ground through sites of contested memory in guises that, sometimes with the aid of prosthetic devices, draw attention to the abject body, Yoon opens herself up to radical encounters. In The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul) she delves into the histories of Japanese colonialism and American imperialism in Korea by moving between the Japanese and United States embassies in Seoul; in 2012’s Beneath she probes the collective unconscious of European modernism in the Vienna of Sigmund Freud, where civilization and barbarism coexisted in the 1930s. In 2010, Koizumi Meiro (b.1976) similarly represented the postwar body in Voice of a Dead Hero, where the artist crawled along the ground dressed as a Japanese soldier in central Tokyo, haunting shoppers who had long forgotten about the spectre of Japan’s imperial past.

Yoon’s latest projects, such as Living Time, 2019, Untunnelling Vision, 2020, and Mul Maeum, 2022, are her most eloquent reflections on how the body carries history, and how memories travel from one world to another, poetically unfolding the experience of diaspora and migration. While these themes have informed her entire oeuvre, the early works treated diasporic experience as subject matter, while the later ones employ diasporic subjectivity as a philosophical framework—a way of understanding and framing the world. Yoon’s perspective here is best described using Edward Said’s notion of contrapuntalism, which is a term that originally comes from musicology, where it describes the interaction of multiple musical lines intertwining to create polyphony.

Living Time foregrounds the intergenerational transmission of traumatic histories through bodies across oceans and continents, whereas in Untunnelling Vision Yoon seeks to set multiple traumas, histories, and possibilities of connection in relation to one another. In the penultimate scene, which features BIPOC participants joining to create polyphony using musical instruments of their own making, Yoon’s contrapuntal vision for a future comes into focus. Mul Maeum takes this awareness of multiple dimensions and experiences even further, to include birds and the planet we live on, in order to imagine new relational futures beyond colonialism, militarism, and the Anthropocene Era—the current geological age in which human activity is responsible for geological, environmental, and climate change.

Lands, Histories, Environment

Just as bodies carry memories, lands carry histories. In placing her own body and the bodies of her family and friends in juxtaposition with different lands in works ranging from Touring Home From Away, 1998, which features Prince Edward Island, to Long View, 2017, which features Pacific Rim National Park Reserve, Yoon’s art reveals the ways in which these bodies activate histories of trauma, war, nation-building, militarism, colonialism, and settler-colonialism through entangled collective histories.

Yoon’s work questioning settler-colonial claims to the land, its stewardship, and the construction of nationhood emerged in the 1990s against the backdrop of Canada’s ongoing identity crisis, which was punctuated by the Kanesatake Resistance (Oka Crisis) in 1990 and the second referendum on Quebec sovereignty in 1995. A rejection of multiculturalism as a model for inclusion of people of colour into the settler-colonial state, Yoon’s projects were prescient in their insistence on decolonization. For example, A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996, was an early critique of the Group of Seven and its use of landscape painting to claim lands that were constructed as empty for the settler-colonial nation. Strategically situated against the exhibition The Group of Seven: Art for a Nation, 1996, at the Vancouver Art Gallery (organized by the National Gallery of Canada), this foundational work in the history of Canadian art was at once an early work of socially engaged art, institutional critique, and a critical reimagining of the relationship between photography and painting that exceeded the aspirational claims of Vancouver photo-conceptualism.

In Touring Home From Away, Yoon demonstrates how the tourist industry remakes the land into a white settler-colonial playground of leisure destinations that erase Indigenous presence and exclude racialized bodies, imagining these Canadians as perpetual foreigners. In the work, Yoon enacts a structural critique of settler-colonialism by bringing attention to ancestral burial grounds that have become a golf course. She stands alongside John Joe Sark, Keptin of the Mi’kmaq Grand Council, who was appointed as Mi’kmaq ambassador to the Vatican and the United Nations Human Rights Commission in Geneva in 1994. They look away from the viewer, inviting us to see the land from an unaccustomed perspective, mirroring the work that Sark was doing to bring Indigenous perspectives to international bodies. Rather than agitating for inclusion into white settler-colonial structures, Yoon questions the fundamental colonial structures and assumptions of Canada; instead of seeking to benefit from the situational privilege of settlers of colour on Canadian soil, she foregrounds Indigenous leaders. With Touring Home From Away, Yoon began a continuing process of developing treaty relationships that aim at reparative coexistence.

Growing out of her critique of colonialism and its attendant focus on modernity and progress, in the 2010s Yoon turned to consider the question of our relationship to the land through the lens of the Anthropocene. For Yoon, the extractive and violent relationship we have to the land is a consequence of post-Renaissance paradigms that have placed humans at the apex of a natural world that is literally measured according to human scales, ordered according to European knowledge structures, and imagined to be at our disposal. This analysis is echoed by the work of Indigenous and decolonial climate activists such as Indigenous Climate Action (established in 2015), Walter Mignolo, and Kathryn Yusoff, as well as by the digital publication and artwork Feral Atlas: The More-Than-Human Anthropocene, 2020–21. Several of Yoon’s highly researched projects, such as Other Hauntings (Song), 2016, Long View, 2017, Living Time, 2019, and Testing Ground, 2019, consider how the use of land for military bases and testing sites continues to haunt the present. Untunnelling Vision, 2020, takes these themes even further, as it warns of the human and environmental devastation triggered by the “tunnel vision” of colonialism, militarism, and extractive capitalism, but also offers us pathways of “relaxing into relation.”

Since 2012, Yoon’s work has explored relationships with the land that extend beyond human communities. In works such as the Living Time photographs of 2019, human figures—friends, relatives, and residents from the artistic community of Hornby Island—are dwarfed by the trees that give them shelter. Here Yoon plays on Vancouver-based photographer Marian Penner Bancroft’s (b.1947) portrait of the tree that was the site of the first Mennonite gathering in South Russia, By Land and Sea (Prospect and Refuge), 1999–2000. In Yoon’s Living Time photographs, the tree functions as a site of emplacement or literal rootedness, but also as source of life. The figures lie among the tree’s roots, a horizontal image of co-dependency with the Earth as well as the evanescence of human life when measured in geological years.

Relationality and Communities

“Relationality” is a term used extensively by Yoon to describe her work, on the level of both theory and practice. Yoon understands individuals and environments as being mutually entangled, such that they shape each other. Within this dynamic is an insistence on the singularity of particular histories and identities—especially difficult histories—that also advocates for multidirectional dialogue. This is how relationality enters into Yoon’s practice, activating exchanges and building solidarities across siloed communities in projects such as Untunnelling Vision, 2020.

Yoon’s early work, most notably Souvenirs of the Self, 1991, has sometimes been understood as advocating for the inclusion of racialized immigrants into the settler-colonial narrative of Canadian multiculturalism. This is a misreading. Yoon is more ambitious than that, proposing a new poetics of relation that imagines different ways of being and being together that constitute a repudiation of official multiculturalism. In the worldview of relationality—a concept taken from the critical essays of the Martinique poet Édouard Glissant—identities are not fixed and siloed, but rather are articulated in relation to others. This worldview accounts for the way Yoon’s work expands from its early focus on Canada’s nation-building project into a critique of colonialism in Canada and Korea, to then move on to its later concern with strategies of repair, radical hospitality, and the environment.

In the early work A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996, Yoon creates social relationships as part of the photographic strategy. As opposed to the practice of Jeff Wall, who staged every aspect of the subjects within the image as a mode of self-contained and self-referential “picture-making,” the subjects of A Group of Sixty-Seven exist outside the image, in relation to each other and to Yoon. Yoon did not simply photograph these members of the Korean Canadian community; she shared a meal with them, as well as memories of their experiences of displacement and racism as immigrants to Canada. The resulting images are relational, challenging viewers to consider whether and why they might see racialized bodies as anomalous against the settler-colonial depictions of land in paintings by Emily Carr (1871–1945) and Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970). The images also function as an archive of a community, piercing through the artwork’s presence as museum piece with an emotional charge for viewers who have parallel experiences or personally know the individuals pictured.

In Touring Home From Away, 1998, and Untunnelling Vision, 2020, relationality takes a different turn, as Yoon makes a structural critique of white settler-colonialism that brings together the concerns of racialized immigrants and Indigenous peoples. In both works, the two communities think with and alongside one another with the intention of transforming worldmaking practices from extraction to interdependence. Touring Home From Away shows Yoon with John Joe Sark, Keptin of the Mi’kmaq Grand Council, gazing over a golf course that used to be ancestral burial grounds, unlearning immigrant claims to belonging within settler-colonial structures. For Untunnelling Vision, Yoon organized a series of workshops entitled “Relation Making in the Context of Racism and Settler-Colonialism,” led by her sister Jin-Sun Yoon, an activist and community organizer. These put Indigenous and racialized youth in conversation with one another through practices of deep listening and sharing.

The resulting conversations were informed by the American physicist and feminist philosopher Karen Barad’s notion of “intra-action,” a term that describes how it is through encounters with others that individuals are constituted and shaped in relation to one another. This term is an important one for Yoon, as a model of relationality that reconfigures our notions of individualism. These conversations shaped the radically relational performances for Untunnelling Vision. Here Yoon, like Barad, theorizes relationality as a mode of co-constituting beings, and of searching for new ways of being in the world.

-

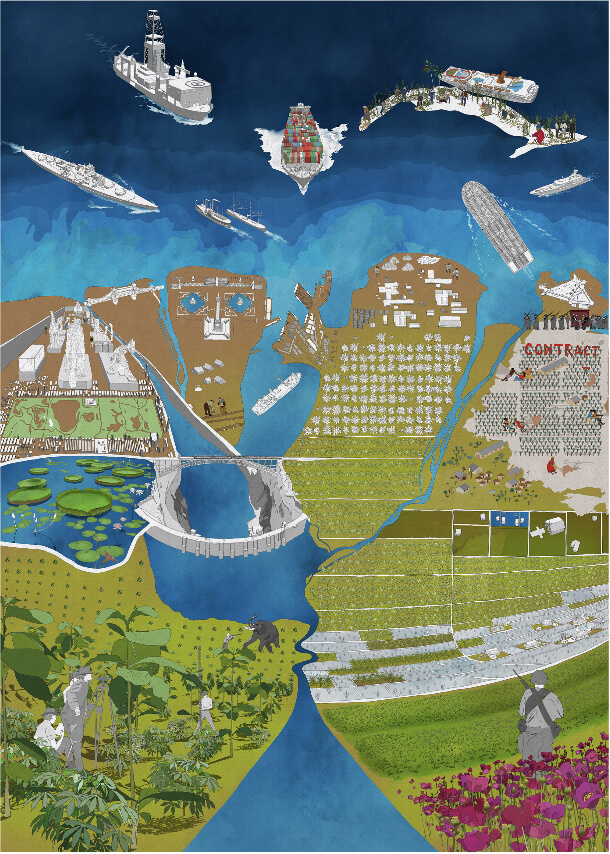

Graphic recording by Tiaré Jung / Drawing Change from the workshop “Relation Making in the Context of Racism and Settler-Colonialism,” for Untunnelling Vision Anti-Racism Workshop facilitated by sister Jin-sun Yoon, Calgary, 2019

-

Graphic recording by Tiaré Jung / Drawing Change from the workshop “Relation Making in the Context of Racism and Settler-Colonialism,” for Untunnelling Vision Anti-Racism Workshop facilitated by sister Jin-sun Yoon, Calgary, 2019

This Time Being, 2013, is a series of abstract sculptural portraits in which form is created through relation. A soft piece of rubber is twisted, smoothed, draped, and transformed in a pas de deux with its surroundings, always itself but also in constant physical relation to them. Interpenetration of the human and non-human worlds is a focus of Yoon’s most recent work, especially Mul Maeum, 2022, where she uses formal tactics to represent the flow of migrating birds and of people through three sites on the Korean peninsula that are connected by water. Flow, both depicted (of water, of birds, and of people) and formally embodied (through experimental camera work, collage, and coloured abstractions), suggests ways of knowing beyond strict binary categories, and ways of being that are necessary for more sustainable futures.

Engagements with Time

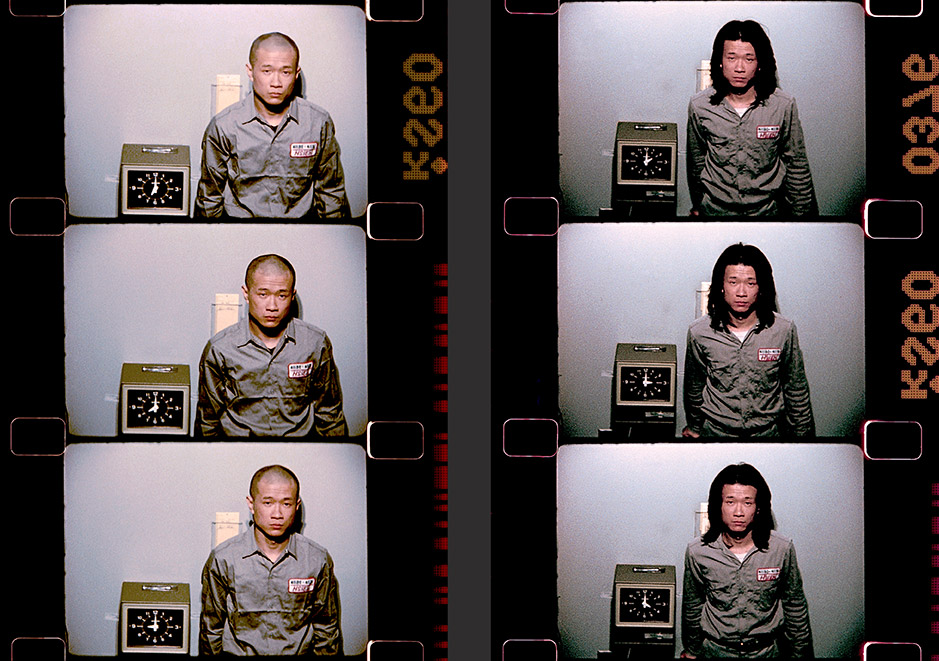

Time figures in Yoon’s oeuvre as subject matter, medium, scale, and philosophical inquiry. As subject matter, time tracks the lives of Yoon’s family as photographic subjects. This practice brings into view the passage of time, as in the Taiwanese American performance artist Tehching Hsieh’s (b.1950) One Year Performances (Time Clock Piece), 1980–81, where he photographed himself punching a time clock once an hour for a year, but sidesteps the artificiality of modern systems of timekeeping, what the French philosopher Henri Bergson calls “objective time,” focusing instead on “la durée” or the experience of passing time. Over the course of Yoon’s oeuvre, viewers have seen her mother and father age, and her son and daughter grow from wailing babies (in Intersection 2, 1998, for instance) into eloquent young adults. In works such as Long View, 2017, where her parents and children appear on the beach, Yoon creates new worlds and relations with her family, friends, and communities. Family, in other words, is bound up in a world-making practice in her work that unfolds over time: its own world, with its own internal time.

When Yoon embraces video and performance, she begins to treat time as medium, situating her work within an intergenerational history of bodies, or historical time. Her first video work, between departure and arrival, 1997, emphasized this temporal engagement with an installation of two clocks on the wall indicating literal and emotional time zones. The 2006 The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul) is a work of durational performance art. Here, the slowness of Yoon’s horizontal journey through the city is a necessary contrast with the breakneck pace of progress against which the work is posed. It reveals the undercurrents of that progress—what is sacrificed and what is lost to South Korea’s single-minded devotion to forward momentum.

In her work Living Time, 2019, which comprises both photographs and a video, she takes the metaphor of intergenerational histories carried in the body and makes it literal, draping her own body over that of her camouflage-clad son, who carries her through the woods on his back. Juxtaposed on a second screen, archival footage depicts previous generations of displaced mothers carrying children on their backs to safety during Korean War migrations.

In Mul Maeum, 2022, time functions at a geological scale. It measures the outsize importance that humans have attributed to themselves as individuals with respect to the planet, as Yoon advocates for more sustainable and relational living. As with the American interdisciplinary artist Sarah Cameron Sunde’s 36.5 / A Durational Performance with the Sea, 2013, where the artist stands in a tidal area for a full tidal cycle while the water moves around her, Yoon’s work juxtaposes historical, or human-scale, time against geological time in a gesture that highlights human vulnerability and the urgency of environmental justice.

Yoon’s late career engagements with time are philosophically driven, seeking new ways of conceptualizing time and existence. Through the metaphor of carrying, works such as the Living Time video reflect upon the question of how memory is carried and passed from one generation to another. Time, for Yoon, is not strictly linear, but affective and living; moments of the past are activated in the present. Space-time is connected through sites or bodies, as Singaporean new media artist Ho Tzu Nyen (b.1976) does in Hotel Aporia, 2019, which critically explores repressed Japanese war memories from the Second World War through a cinematic haunting of the Kirakutei, the hotel that hosted a last dinner for the Kusanagi Kamikaze squadron. Similarly, Yoon activates forgotten palimpsests of historical engagement such as the sites of Testing Ground, 2019, and Untunnelling Vision, 2020, which were used for military exercises.

In Testing Ground, 2019, and Untunnelling Vision, 2020, Yoon develops her notion of “vertical time,” which reorganizes modern Western notions of linear time from a principle of abstract chronology to a principle of embodiment in bodies and lands. In vertical time, an image is joined with others from the past or future, and moves through cycles that return and repeat, creating additional layers of meaning and existence. For Yoon, these separate layers can be joined together and reimagined, offering the possibility of repair.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements