A Group of Sixty-Seven 1996

Jin-me Yoon, Installation view of A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996

Two grids of 67 framed chromogenic prints for a total of 134 prints and 1 name panel, 47.5 x 60.5 cm each

Vancouver Art Gallery and Portrait Gallery of Canada / Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

Photograph by Rachel Topham Photography / Museum of Vancouver

A Group of Sixty-Seven is perhaps Jin-me Yoon’s most recognizable work. Existing in multiple formats, it consists of two grids of sixty-seven portraits of the Korean Canadian community in Vancouver standing in front of two paintings: Maligne Lake, Jasper Park, 1924, by Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970) and Old Time Coast Village, 1929–30, by Emily Carr (1871–1945). Yoon created it in 1996, the year that the National Gallery of Canada’s The Group of Seven: Art for a Nation travelled to the Vancouver Art Gallery—which was one year after the second referendum on Quebec sovereignty, the same year the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples recommended a public inquiry into residential schools, and a year before the handover of Hong Kong to China and a large increase in immigration from Hong Kong to Vancouver. In this fraught environment, Art for a Nation asserted white, anglophone settler-colonial narratives, trumpeting the Group of Seven’s appropriation and mastery of Canadian landscape in painted form.

-

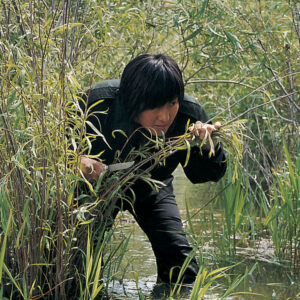

Jin-me Yoon, A Group of Sixty-Seven (front detail), 1996

Chromogenic print, 47.5 x 60.5 cm

Vancouver Art Gallery -

Lawren S. Harris, Maligne Lake, Jasper Park, 1924

Oil on canvas, 122.8 x 152.8 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa -

Jin-me Yoon, A Group of Sixty-Seven (back detail), 1996

Chromogenic print, 47.5 x 60.5 cm

Vancouver Art Gallery -

Emily Carr, Old Time Coast Village, 1929–30

Oil on canvas, 91.3 x 128.7 cm

Vancouver Art Gallery

-

Jin-me Yoon, A Group of Sixty-Seven (front detail), 1996

Chromogenic print, 47.5 x 60.5 cm

Vancouver Art Gallery -

Jin-me Yoon, A Group of Sixty-Seven (back detail), 1996

Chromogenic print, 47.5 x 60.5 cm

Vancouver Art Gallery

The work repeats the strategy of Souvenirs of the Self, 1991, in juxtaposing Asian bodies with iconic Canadian landscapes, but with a representational twist. The photographs are obviously constructed, using visual repetition and stiff, formal poses to call to mind official portraiture, passport photos, and photographs of ethnic types taken by anthropologists, and they demonstrate that a photographic image is not a transparent window on reality but rather a form of representation that functions as a framing device to shape meaning. Yoon calls attention to how painting functions in a similar fashion in Harris’s and Carr’s art, showing how their landscapes are not neutral representations, but settler-colonial claims to terra nullius. In combining and contrasting the people and the paintings, Yoon challenges the racialization that puts Asian bodies beyond the purview of a constructed national identity and demonstrates how white settler-colonialism stages its fictions.

In this, her first foray into social practice and institutional critique, Yoon invited sixty-seven members of the Korean Canadian community (bringing attention to 1967 as the year that restrictions on Asian immigration to Canada were finally lifted) to dinner and conversation at the Vancouver Art Gallery. Reclaiming the space with the heady scent of kimchi, friendly community chatter, and discussions of racism in Canada, Yoon created portrait events with each of the sitters in front of both paintings, whose meanings were recast through this new encounter.

The resulting photographs sparred with the art historical interventions of Vancouver photo-conceptualism, such as The Destroyed Room, 1978, by Jeff Wall (b.1946) (which references The Death of Sardanapalus, 1827, by Eugène Delacroix [1798–1863]), and mounted a challenge to the Group of Seven and Canadian landscape painting that has been taken up by other artists. Just months after A Group of Sixty-Seven, Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun (b.1957) mounted his own critical dialogue with Emily Carr: his trees, stolen back from Carr, are haunted with Haida ancestors. Shawna Dempsey and Lorri Millan engage in an analogous dialogue with the naturalized heterosexuality of the Canadian landscape in Lesbian National Parks and Services, 1997; and The Value of Comic Sans, 2016, by Sonny Assu (b.1975) imagines urban Indigenous graffiti artists from Carr’s future descending into her paintings to reclaim them.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements