Marion Nicoll was exceptionally committed to technical development and mastery of the materials she worked with throughout her career. She instilled in her students the principle that “technique is a result, not a start.” She considered all her work equally important and finessed her skills using six key processes: painting in watercolour; automatic drawing and painting; painting in oil and acrylic; batik; jewelry; and printmaking. Throughout her practice, the key styles in which she worked included naturalism, automatism, and hard-edge abstraction.

Painting Nature in Watercolour

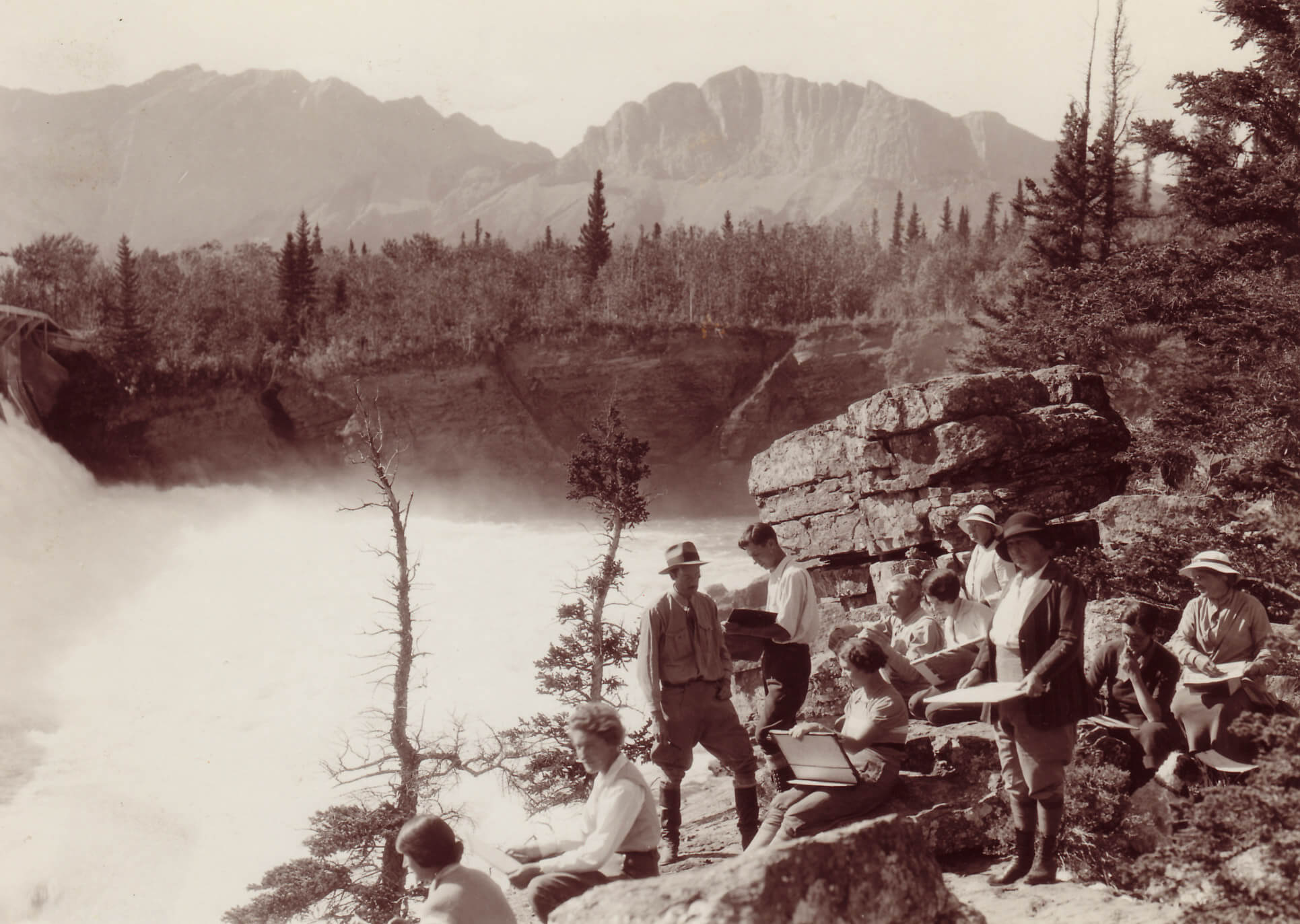

In the 1930s, Nicoll sketched outdoors and camped backcountry in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, as a photograph of her on horseback on the Bow Forest Reserve illustrates. She had been taught by some of Canada’s most important landscapists, including Group of Seven artists Frank Johnston (1888–1949) and Arthur Lismer (1885–1969) at the Ontario College of Art (1926–1929).

It was under study with Alfred Crocker Leighton (1901–1965) at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art in Calgary (1929–1931) that Nicoll solidified her landscape painting skills in watercolour. Her training consolidated her use of tone when applying colour to her drawings, which can be seen in one of her depictions of the Rocky Mountains.

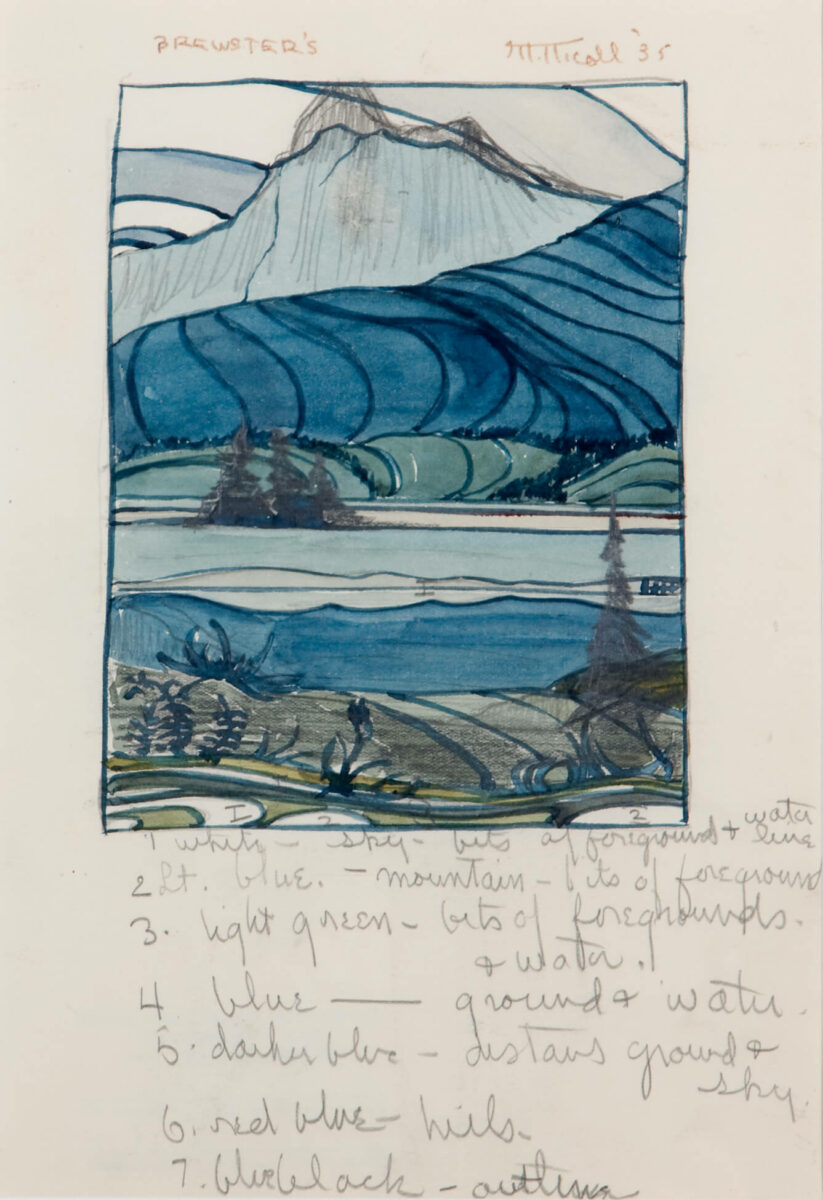

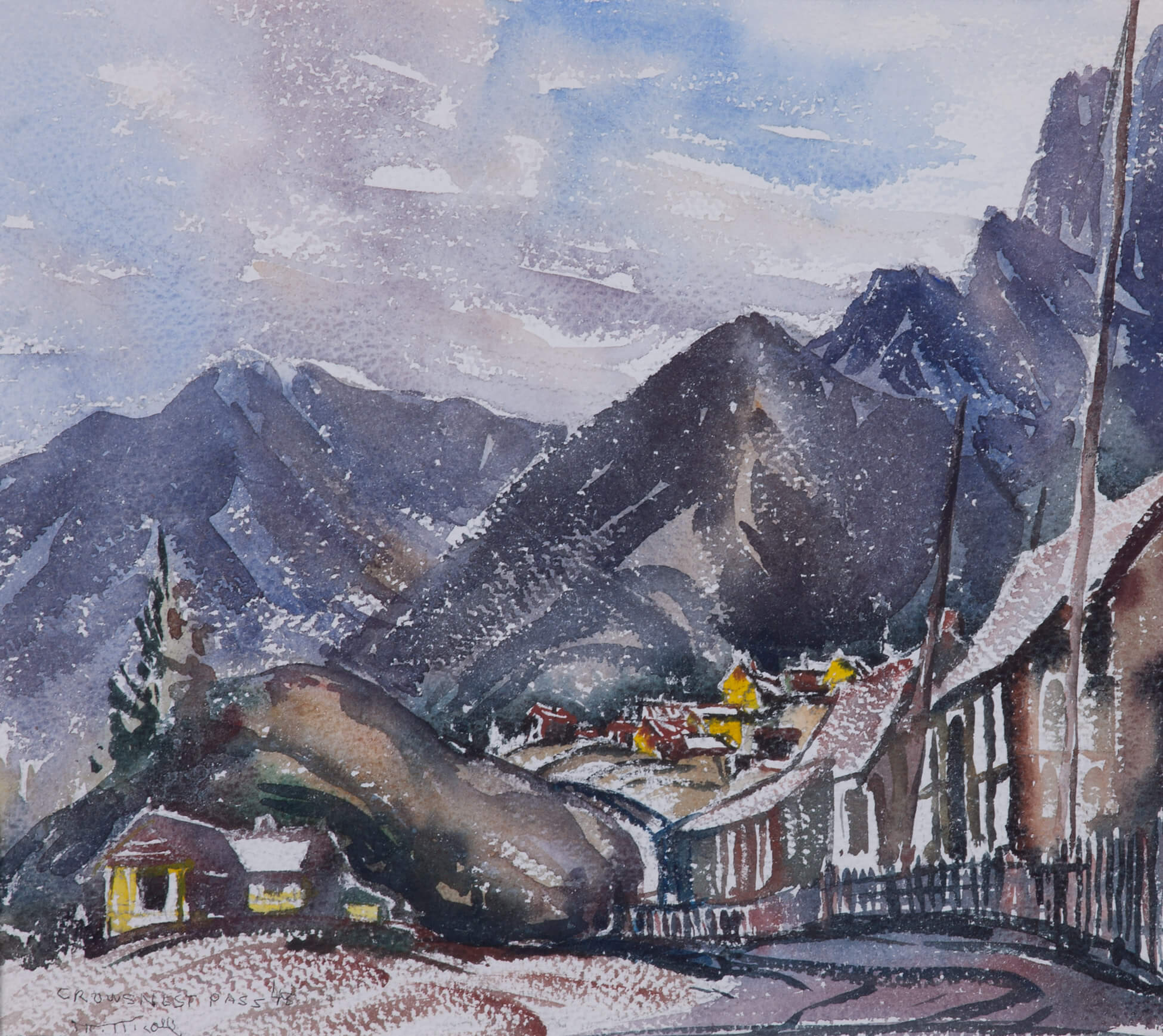

Untitled–Rockies, 1940, includes an under-drawing overlaid with washes of watercolour over which she applied a drier brushwork. Thickened colours were used for elements of the foreground, middle ground, and background river, trees, mountains, and sky. This work can be compared with Leighton’s View of Edmonton from the North Saskatchewan, 1930, which demonstrates his careful attention to detail and use of delicate washes to form the open prairie skies. The palette of earth-tone greens, blues, and browns seen in both artists’ paintings shows how Nicoll observed Leighton’s key lessons in colour harmony. Nicoll’s watercolour Brewster’s, sketched on her 1935 trip to the Brewster’s Guest Ranch in Seebe, Alberta, demonstrates another adaptation of colour harmony. Below this landscape scene, she noted in exquisite detail the blues and greens to be toned with black and white throughout.

Automatic Drawing and Painting

Nicoll made automatic drawings and watercolours from 1946 to the late 1970s, creating dozens of images. When she first began exploring automatism in her thirties, it was a significant departure from her naturalistic work. Her introduction to this Surrealist mode of production came via colleague Jock Macdonald (1897–1960), whom she met at the Banff Summer School in 1946 where both artists were teaching.

Macdonald had come from Vancouver, where he had met Grace Pailthorpe (1883–1971) and attended a lecture she gave on Surrealism in conjunction with her 1944 exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery. Pailthorpe was a physician and surgeon during the First World War, became a Freudian analyst in 1922, and had exhibited in the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London, England. She provided a bridge to European Surrealism for Macdonald, and, in turn, for Nicoll.

The process of working automatically involved being alone, concentrating, and allowing the hand to move freely without planning—Nicoll once compared it to meditation. Macdonald noted his delight at her ongoing commitment: “Ha! Ha!” he exclaimed, “One cannot account for what comes forth and in truth it doesn’t matter. However, now that you find things definitely suggestive of nature forms, you can be sure that the door is now open—Excellent.” Nicoll believed that the practice was integral to her development as an abstract painter.

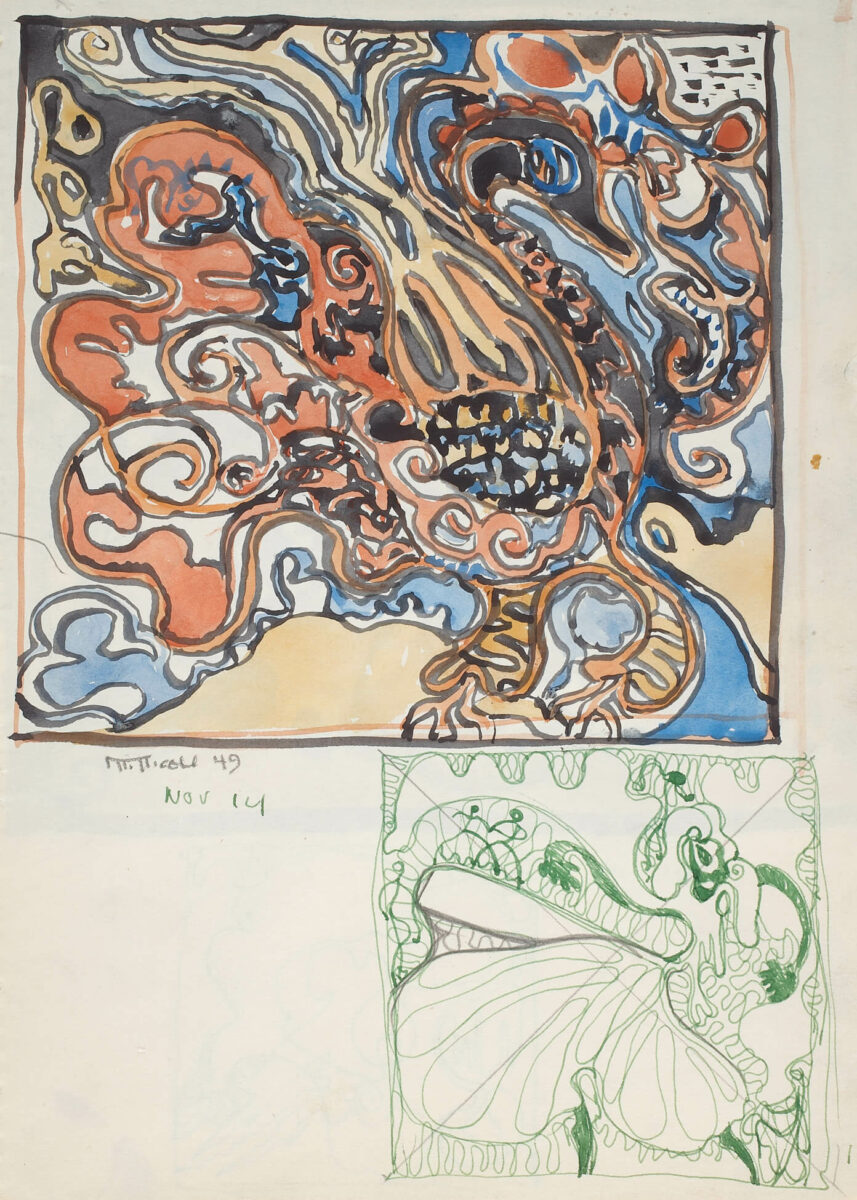

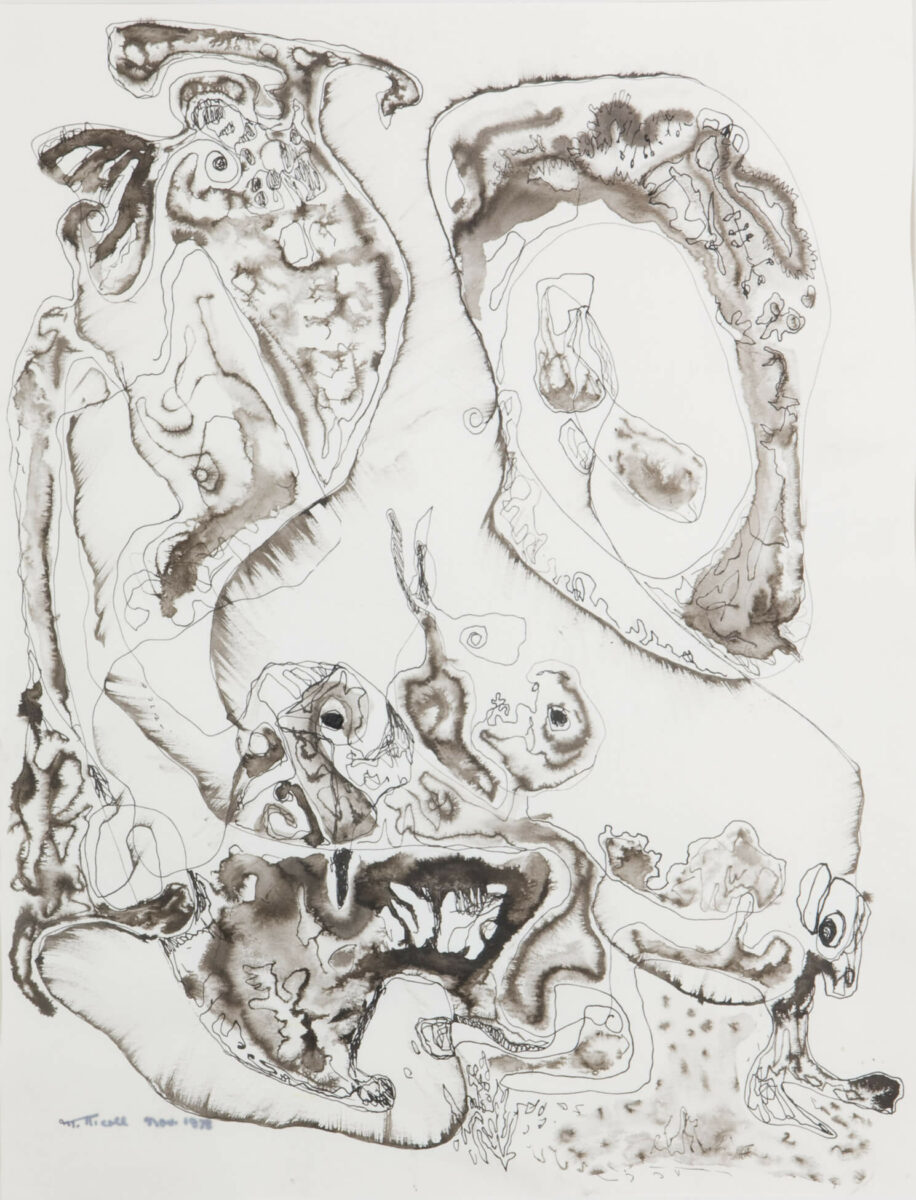

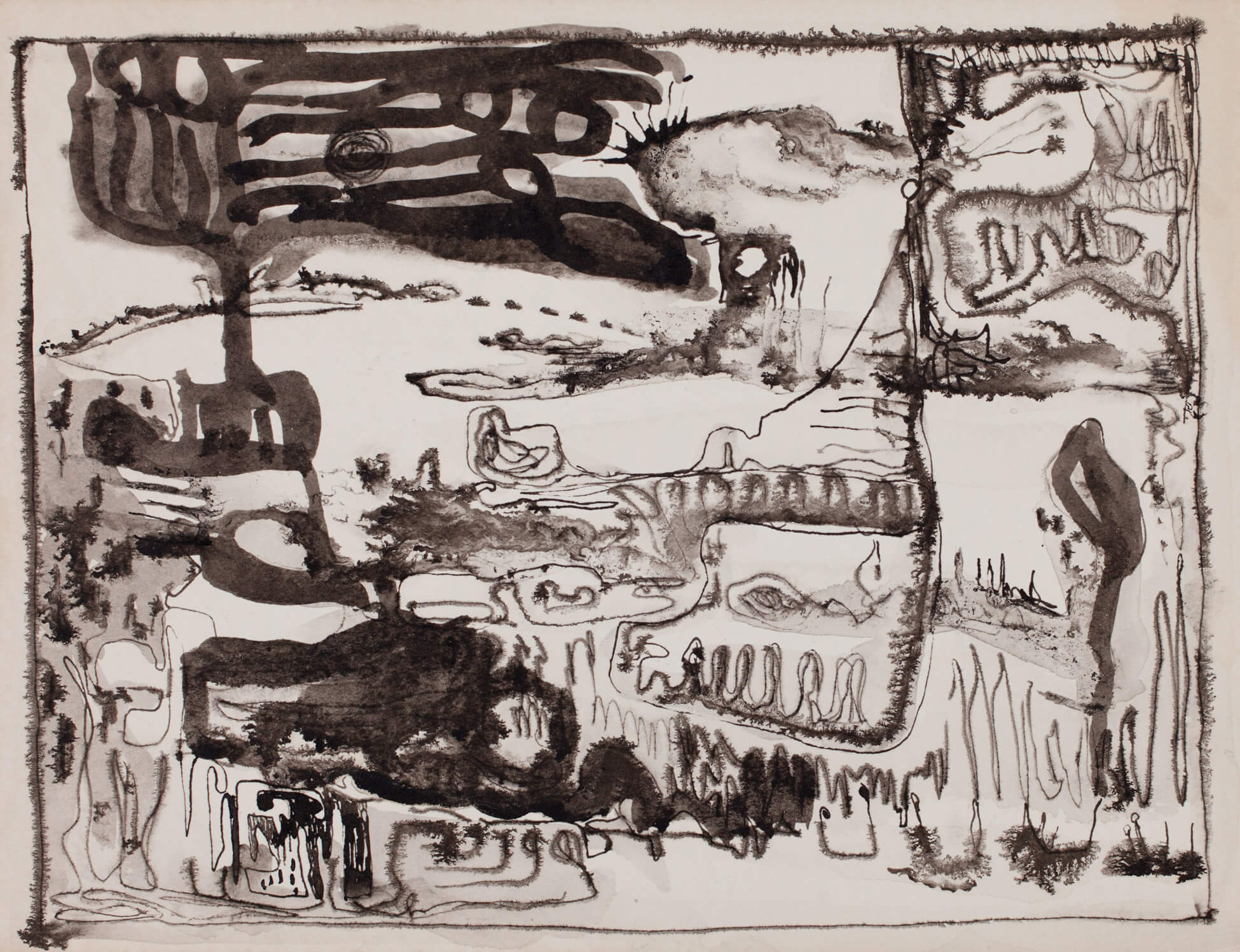

Nicoll made her automatics in pen, pencil, and watercolour and her works range from simple line drawings to complex compositions with fanciful creatures and abstractions. Automatism challenged Nicoll’s tight control over brush and pen and released her from depicting the external world, inviting forth her inner world of imagination. Two examples from the Glenbow collection (both known as Untitled (Automatic Drawing)) from 1948 and 1949 illustrate the fertility of mind she found within. The square-shaped watercolour painted on November 14, 1949, features intersecting lines and forms, and a phallic shape at the centre of the image is suggestive of sexual climax; the ink drawing below the watercolour evokes a conjoined bird- or butterfly-like creature.

The work made on November 11, 1948, blends together her ink under-drawing with watercolour washes—a fluid medium that Nicoll found to welcome elements of chance, in keeping with the automatic process. Figure and ground relationships intermingle, the natural colour of the paper plays its own role in the overall composition, space is no longer governed by perspective, illogical subjects co-exist, light comes from the surface itself, and narrative is irrational.

Gone were the descriptive titles noting where she had been and what she had seen, as she had done in her landscapes: most of her automatics remain untitled, including inscriptions noting only the time of day and/or date of creation. Nicoll continued automatic creation to her last years, despite dexterity challenges posed from her advanced arthritis, because, as she recalled, through automatism, “It was as though I could breathe.” Her 1978 black-and-white ink drawing fills almost the entire page, with lines and washes bleeding from one area to the next.

Oil Painting and a Studio

Nicoll created very few works in oil before 1959. As a landscapist, she had been trained to paint in watercolour and to make oil sketches on small boards. A photograph of her sketching in Sunshine, Alberta, illustrates the plein air process she used—seated with sketch box, panels, paint, and brushes in hand, observing the scene before her. It was, however, in her hard-edge abstracts on stretched canvases, painted from 1959 onwards, that Nicoll developed her finest command over the oil medium.

Using pure oil paint proved challenging because of its long drying time and thick viscosity, but she stayed with the medium for well over a decade once she shifted to hard-edge abstraction. Sometimes she added a paint thinner called Lucite, which enabled a faster drying process, reduced the texture, and enabled her to realize crisply delineated forms. Her shift from a textured landscape to an unmodulated abstract surface is evident in the comparison of a 1946 mountain sketch Untitled Mountain Landscape, with Foothills: I, 1965.

A technical challenge Nicoll realized in the early 1960s was that her working space was insufficient to accommodate increases to the scale of her abstractions—paintings such as Bowness Road, 2 AM, 1963, were nearly two metres in length. With the support of her husband’s engineering skills, she designed a studio addition for their Bowness home, filled with natural light and space enough to step back from the paintings in order to assess their impact before public exhibition. It was finished by the end of 1963, and in 1965 the finishing touch of an easel from the studio of Post-Impressionist artist Henri Rousseau (1844–1910) (acquired from Alfred Crocker Leighton) made it Nicoll’s haven. She observed, “It takes a five-foot canvas. When I’m painting longer, I just paint on it sideways. The only thing I’d take with me if I got up and left this place is that easel. The rest of it can stay.”

After his visit to see Nicoll’s new space, American artist Will Barnet (1911–2012) noted, “We shall never forget your beautiful new studio and the curve of the earth as you look out of the studio window and the Chinook clouds. Your work as it were all over the room—was superb.” Most of Nicoll’s abstracts were done in oil except for her very last paintings, such as One Year, 1971. In that instance, she shifted to plastic-based acrylics because she liked the medium’s suitability to hard-edge compositions and “because you can overpaint and it dries fast.”

Another important technique in Nicoll’s abstractions after New York was her change to working in a serial format. Between 1960 and 1968, she developed nine bodies of hard-edge painting in series—Presence (I–IX), Alberta (I–XIV), Chinook (I–IV), Ritual (I–II), Omen (I–II), Calgary (I–IV), Foothills (I–II), Guaycura (I–II), and Runes (I–II). By making series, she was able to thematically expand an idea over several paintings. Her titles gave structural and sequential coherence to each work by including the series title followed by a roman numeral and a subtitle. They were inextricably tied to the meaning of her abstractions, serving as constant reminders of the passing of time through cycles natural and mechanical (Calgary III, 4 AM, 1966, and One Year, 1971) and as reflections on the brevity of life and humanity’s place in the natural order.

Sculpture to Wear

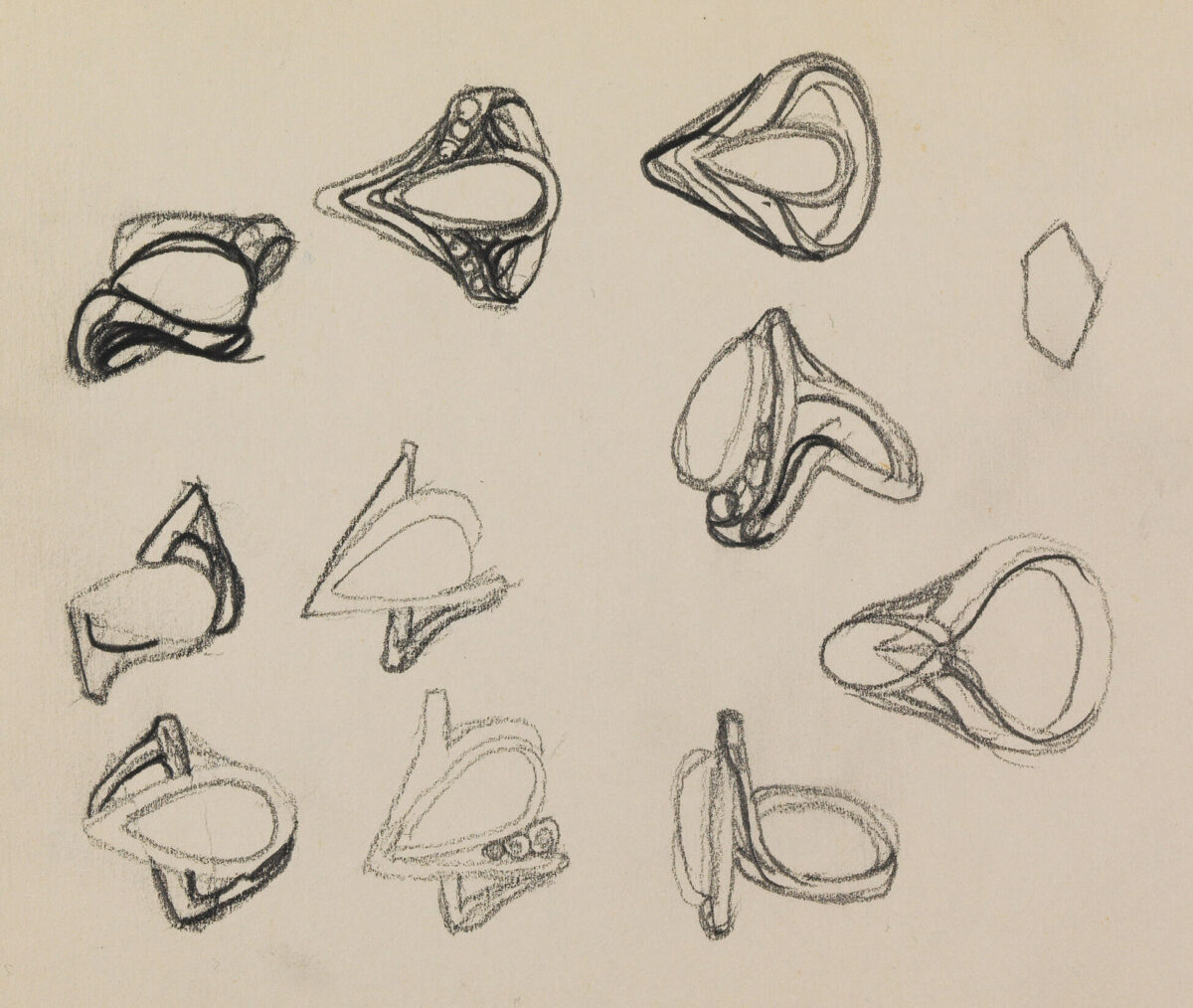

All of Nicoll’s rare jewelry pieces in metal and gemstones remain in private collections, making technical and stylistic study of them a challenge. Most were created after she travelled to Vancouver in 1956, where she studied with silversmith J. Christjansen. She considered her metal work “wearable art,” having declared it such at the event Sculpture to Wear: Bronze, Silver and Gold, and sometimes exhibited her jewelry alongside her paintings.

The sterling silver pin Plateau (location unknown) was included in the First National Fine Crafts Exhibition organized by the National Gallery of Canada, which toured to three Canadian art galleries and the Canadian Pavilion in the Universal and International Exhibition, Brussels. In Albertacraft ’62, Nicoll showed twelve works, including rings, pin-pendants, and earrings, alongside her abstract painting Alberta XII: First Snow, c.1962. The pin-pendant Snow Fence, c.1956–62, was included in that exhibition.

Nicoll’s sketches for her metal work, such as a page of designs for finger rings in the Glenbow collection, illustrate that she thoroughly considered the relationships between stones and metals, her approach modern and simplified, like her abstract paintings. Her amethyst and silver bracelet, received by its current owner as a high school graduation gift from her mother, shows Nicoll’s careful planning of repeating forms and detailed attention to the joins between forms and clasp. A silver bracelet and matching earrings are believed to have been purchased as an anniversary gift. Stylistically, Nicoll’s metal works are consistent with her abstractions: on the one hand, they embrace the freedom of line characteristic of her automatics and, on the other hand, they continue the repeating shapes of her hard-edged abstractions.

Working with metals required great precision and Nicoll is known to have used a custom-designed tool that supported her hand to assist her fabrication. Consistent with her paintings, the natural world informed her subjects and modern approach: her jewelry included such titles as Winter Sun, The City, Pedestrian, Winter Seed, Grass and Reflected Sun, and Pine Needles (all works c.1956–62). That she was also sufficiently imaginative to create the unorthodox thumb-ring and design thematically matched sets of pins and earrings is testimony to the technical, stylistic, and conceptual innovation she achieved with metals and gemstones.

Batik

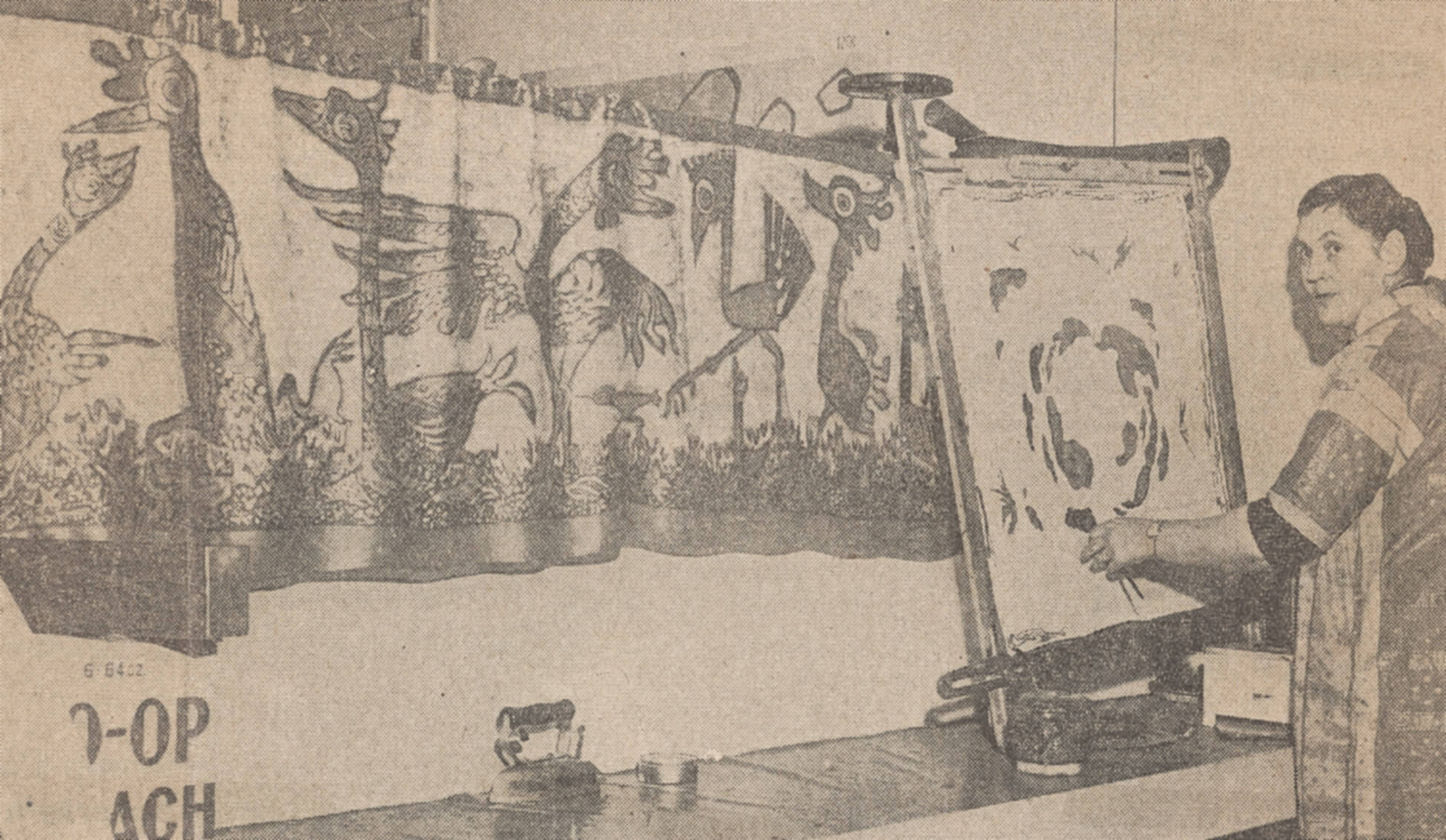

By the 1950s, Nicoll was considered an expert on the ancient Javanese practice of creating designs in wax resist on fabrics, known as batik. She had first learned the process as a student at the Ontario College of Art and undertook further training at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, London, England, in 1937–38. The technique later became part of her teaching at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art, and she sold many works privately for income. By the time the Government of Alberta commissioned her to write on the subject in 1953, she had about twenty years of experience with the medium. She also participated in public interviews and demonstrations, notably with Procession of Birds, 1956, for which she is known to have won “a top prize in a Quebec exhibition.”

Nicoll’s how-to manual Batik explained the detail required to produce work in this medium. The artist begins with a preliminary drawing and sourcing of materials—fabric, a stretcher, paraffin, beeswax, aniline dyes, pins, iron, and cleaning materials including such mordants as acids, distilled water, calcium carbonate, and lead-free gasoline. The design is drawn onto the fabric with soft pencil and wax is applied to those areas to retain the natural fabric colour.

Each colour appearing in the final image requires a separate dyeing process. Thus, Nicoll recommended a key learning from her automatics—incorporate the colour of the substrate in your design to save one step in dyeing. Cleaning processes included application of a hot iron and gasoline bath to remove wax residues. Finally, the batik was dipped in mordant, washed, rinsed, and pressed with an iron to smooth out the fabric.

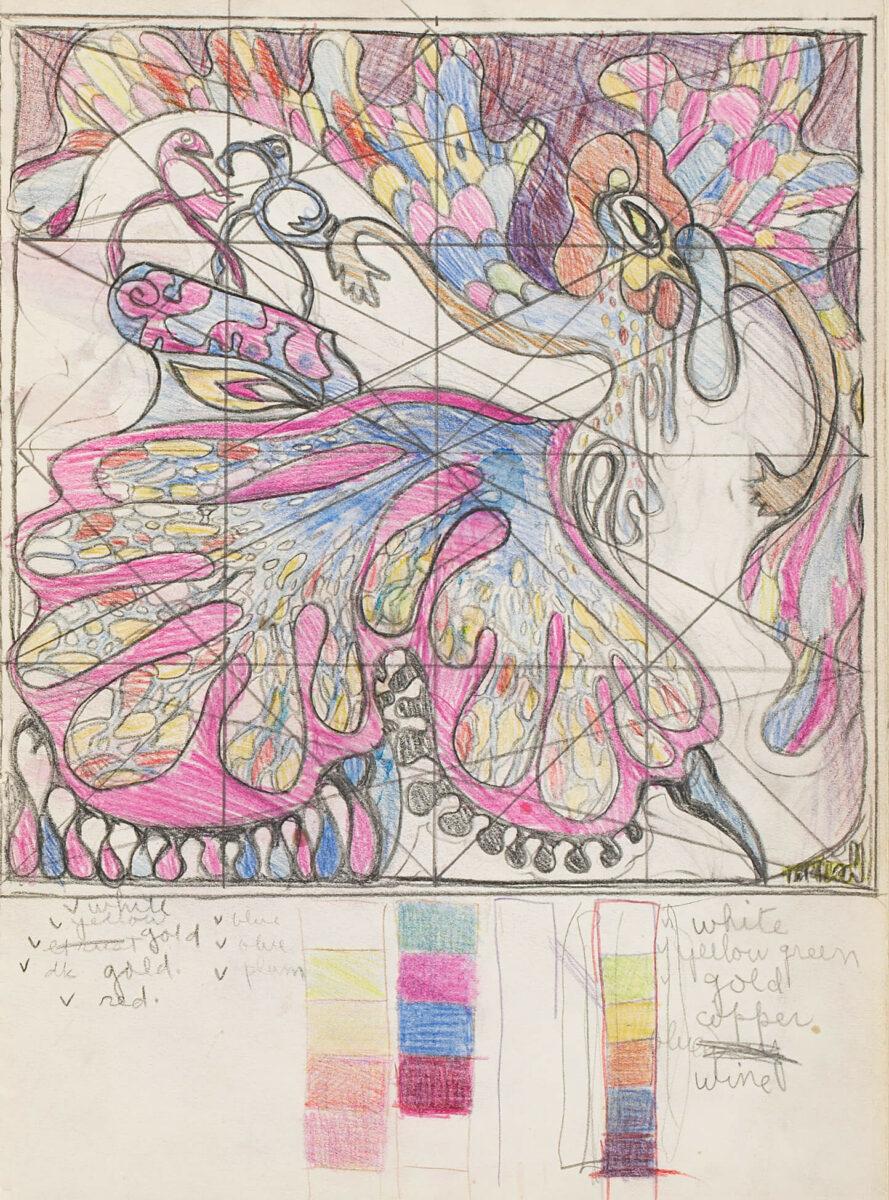

Stylistically, Nicoll’s batiks of the 1950s were an extension of her automatic paintings, featuring fanciful imagery drawn from her inner world and a flowing, linear quality throughout. Nicoll’s Sketchbook #12 shows how she moved easily between drawing and batik to apply the process of automatic expression. The front and back pages show planning she did for compositions similar to those in Procession of Birds. As well, the front includes her colour palette—white, copper, wine, yellow-green, gold, and blue.

Nicoll’s batiks were highly coveted in the private market and earned her representation with New York gallerist Bertha Schaefer. She was also highly regarded for her teaching of fabric arts, so much so that Calgary artist John K. Esler (1933–2001) organized an exhibition of student work in Nicoll’s honour, Calgary Fabric Wall Hangings.

Printmaking

-

Marion Nicoll, Christmas Tree, 1952

Clay print on paper, 17.7 x 15.2 cm

Alberta Foundation for the Arts, Edmonton -

Marion Nicoll, Butterflies, 1953

Clay mould, 28 x 34.3 cm

Glenbow Museum, Calgary -

Marion Nicoll, Butterflies, 1953

Clay print on paper, 28 x 34.3 cm

Glenbow Museum, Calgary

Nicoll made prints throughout her career, including in linocut and silkscreen processes, but it was in the 1950s that she began working innovatively in non-traditional media such as clay and collography (cardboard build-up). Christmas Tree, 1952, was her first work using a clay support, a matrix she preferred for its malleability. In it, she incorporated fanciful imagery developed from her automatics.

The original block and finished print for Butterflies, 1953, show Nicoll’s continued work with automatism and her innovation in the clay medium. Consistent with the traditional block-relief print process, forms left in relief appear in the print as colours and forms incised into the clay remain uncoloured. However, the inscriptions she noted at the bottom of the print reveal this to be anything but a traditional print: “incised with knife, fork, spoon, round washer and hair clip.” Using these carving tools, Nicoll challenged the printmaker’s trade while overturning conventional associations of those objects with household gender roles. Eating utensils from the kitchen, bolts and washers from the tool room, and hair clips from the vanity found new utility in her hands.

Relative to the dominant use of lithography, silkscreen, and metal-plate etching processes in contemporary printmaking, Nicoll rewrote the rules as a feminist and artist in her clay prints. One of her first abstract prints, Expanding White, 1960, is another example of innovation. Printing on the unusual surface of a J Cloth brand household cleaning towel, Nicoll explored the two-colour woven pattern intrinsic to the J Cloth to create a mottled look with textural variations. Her title draws attention to the role played by white throughout the composition: the white areas create a maze-like geometric pattern and serve as an outside border, qualities consistent with her hard-edge painting practice.

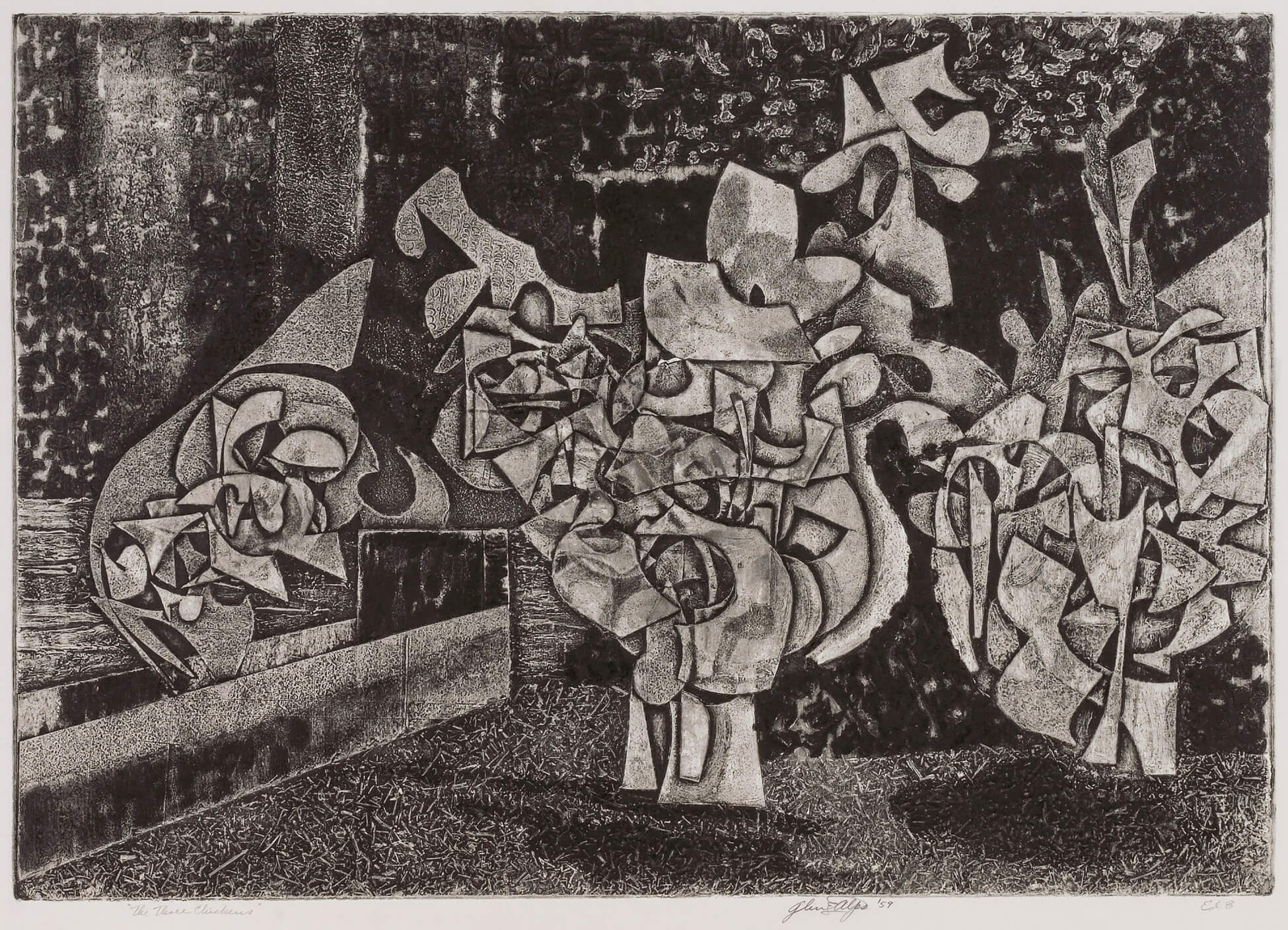

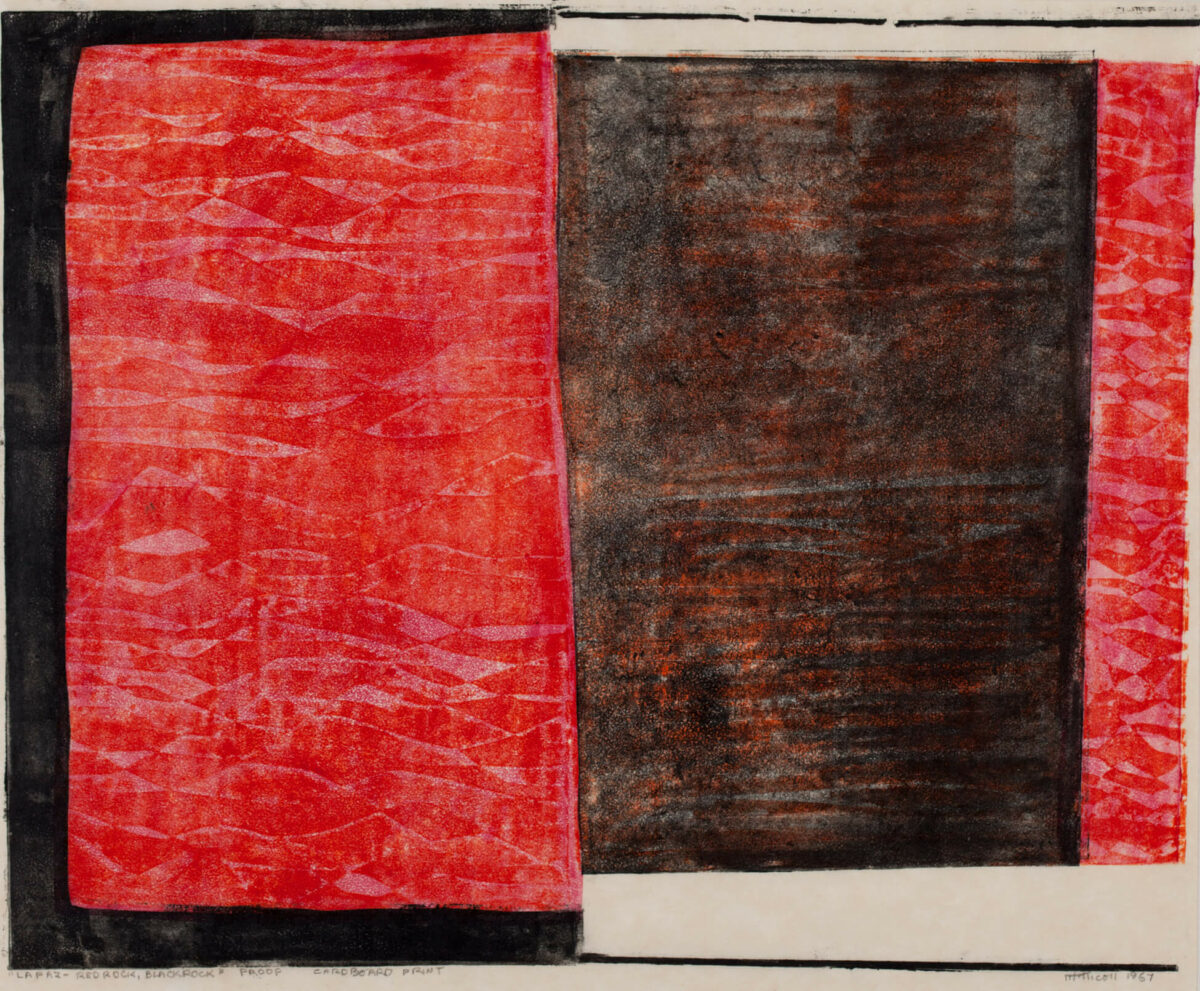

As a printmaker, Nicoll is known for her work with collography, which she began exploring in 1965. She may have learned about the possibilities of this substrate while living in New York in 1958–59, since Glen Alps (1914–1996), who is attributed with discovering the process, had recently shown his collographs at the Brooklyn Museum. La Paz, Red Rock Black Rock, 1967, illustrates how the collograph could yield larger areas of colour and create a play of negative and positive geometries.

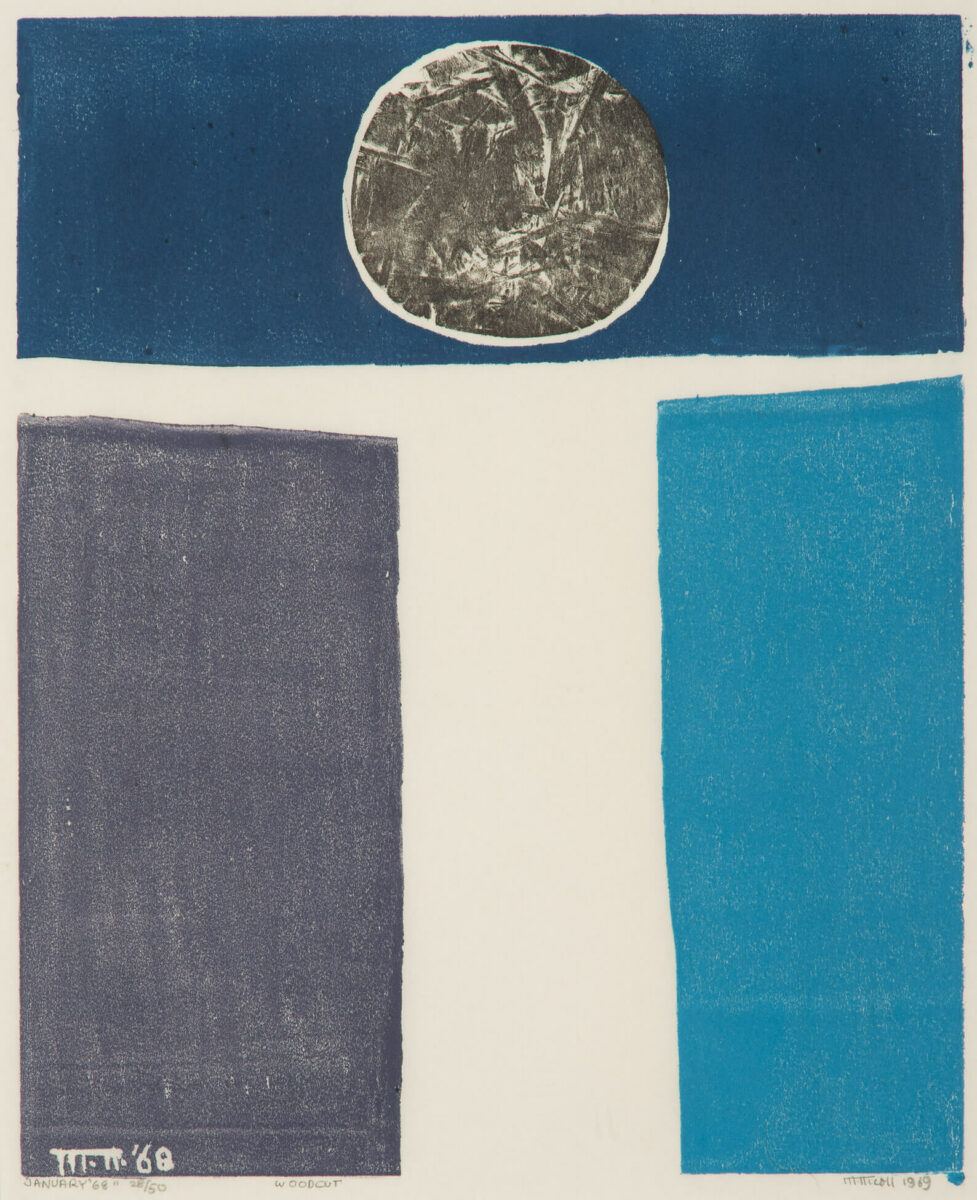

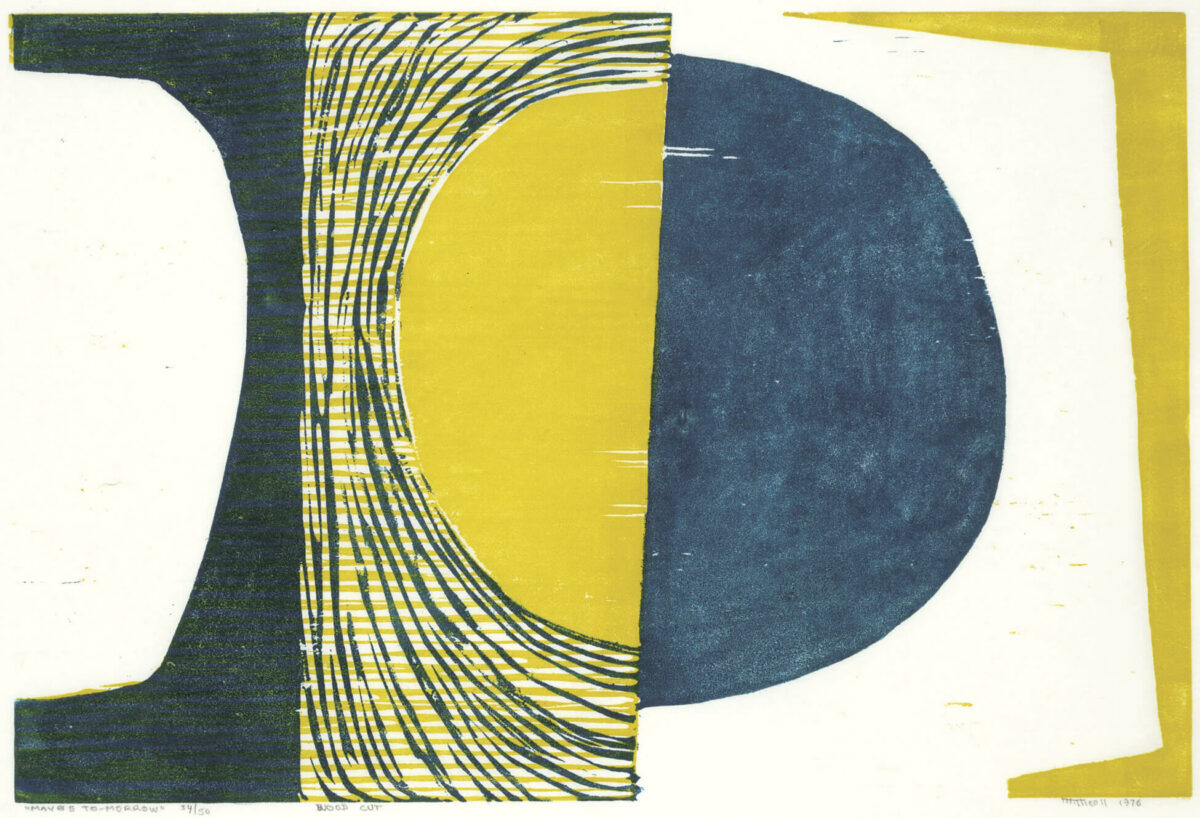

Some of Nicoll’s prints were extensions of her practice: Waiting, 1965, and January ’68, 1968, both followed completion of her abstract paintings of the same titles. For January ’68, Nicoll embraced a more traditional method in her choice of woodcut with the result that she was able to develop one of her largest print editions—numbering fifty—for this image. Edition sizes for works on her more experimental and fragile matrixes such as collography tended to be smaller: Waiting and La Paz, Red Rock Black Rock were realized in editions of fourteen and fifteen prints respectively.

Given the many media with which Nicoll worked and excelled, she truly was a polymath. In printmaking, she is recognized for attaining “remarkable results with little or no equipment” and for using “unconventional materials such as plasticine, matboard, and string for the matrix.” In batik fabrication, artists, government officials, and teaching institutions such as the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art looked to her for expertise. In jewelry, her works were so highly coveted that not one of them yet resides in a public art collection. In painting, she sharpened her technical skills each time she changed strategies, from landscape painting to automatism to hard-edge abstraction.

Nicoll wrote little about art, but when she did, she focused on technical skill development, such as her how-to manuals Monoprints (1951) and Batik (1953). She remained steadfast in her commitment to technical excellence and the handmade in an age of mass production and mechanization. For her, though, technique was never more important than the artist’s true goal of self-expression.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements