Marion Nicoll (1909–1985) is regarded as one of Alberta’s earliest abstract painters. A trailblazer for women in the arts, she was a pivotal influence on the generations that followed her. In the isolated and male-dominated creative community of Calgary in the mid-twentieth century, she was one of the few female art instructors working in a post-secondary institution, and in the 1970s became the first woman from the Prairies to be recognized by the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. Undaunted by the limitations placed on her by society, she has earned a lasting legacy in the Canadian cultural landscape.

Early Years and Education

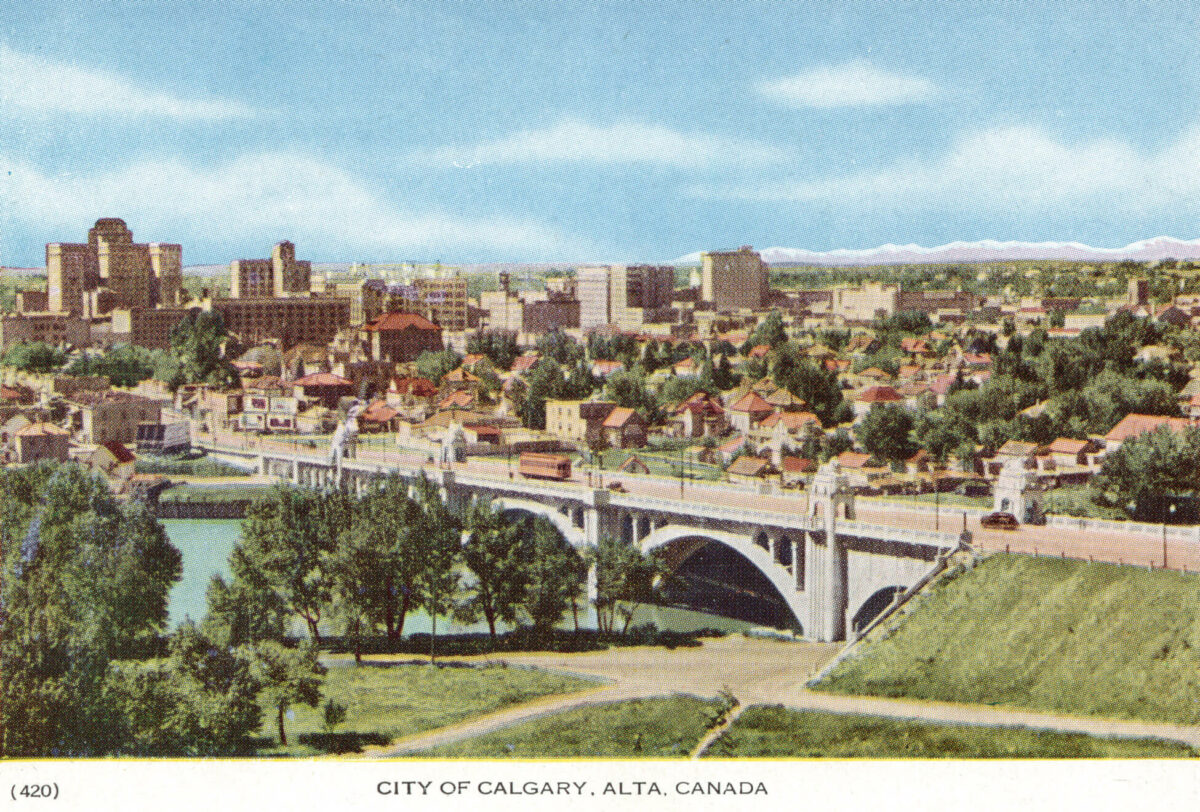

The stories of Marion Nicoll and the city of Calgary, Alberta, are inextricably intertwined, with each coming to define the other’s essential qualities. Born April 11, 1909, Marion Florence Sinclair Mackay was a first-generation settler Canadian, the daughter of immigrants Robert Mackay, of Scottish descent, and Florence Gingras, of Irish and French heritage. Her middle-class Presbyterian family embraced a traditional breadwinner-homemaker model, with her father working as the first superintendent of Calgary’s electric light and power services and associate director of Calgary’s annual Exhibition and Stampede. Her mother gave birth to four children, three of whom died, leaving Marion as the only surviving child.

Florence kept a protective and watchful eye over her daughter’s well-being and encouraged her to remain close to home. As a child, Marion showed an early interest in art, remembering that from age five, she “drew on everything, books, everything else.” Always determined, she convinced her parents to let her set up a basement art studio at the age of thirteen. In adulthood, she turned down her mother’s proposal to study domestic science and household economics with the response, “Absolutely not.”

At Calgary’s Central High School, one of Marion’s earliest teachers was Reginald Llewellyn Harvey (1888–1973), a British landscape painter. He encouraged her to pursue art and her family was very supportive, though her father worried she would never “make a living at art in any form.” Despite this concern, he was willing to fund her studies, and she enrolled at Toronto’s Ontario College of Art (now OCAD University) in 1926, where she studied under portraitist John Alfsen (1902–1971) and Group of Seven landscape artists Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), Frank Johnston (1888–1949), and J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932). Her student colleagues included Toronto’s Frances-Anne Johnston (1910–1987) and, from Alberta, Gwen Kortright Hutton (1909–1978), Annora Brown (1899–1987), and Euphemia McNaught (1901–2002).

After Marion took a trip home to visit family in 1928, her mother prohibited her return to Toronto on account of her being anemic. She transferred to Calgary’s Provincial Institute of Technology and Art (PITA), where she studied under British painter Alfred Crocker Leighton (1900–1965), whose summer landscape classes led to the establishment of what is now the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Unconvinced of her technical skills, Leighton placed Marion in the program’s first year to strengthen her understanding of colour, but within months she was back in the third year. She was appointed a student instructor in 1933 and an instructor in 1935.

A formative highlight during Marion’s studies was encountering the paintings of West Coast artist Emily Carr (1871–1945). An exhibition of her work was brought to PITA, but the administration refused to show it on the grounds that it was “too modern.” Leighton took his students into the locked storeroom where the art was being kept, and they took the canvases out one at a time. Marion remembered being “struck dumb,” and later said that Carr influenced her more than the Group of Seven. Carr’s scenes of British Columbia’s Indigenous communities and coastal landscapes embodied a new modernist vocabulary of bold gestural brushwork and strong colour, and she became one of Marion’s favourite artists.

The censoring of Carr’s show reflected some of the philistine and gendered attitudes toward art and women that persisted in Calgary, systemic barriers that Marion also navigated. She was exposed to few female artists and Carr was an example of independence, resilience, and innovation. Calgary’s infrastructure for the visual arts was only just beginning: there was no civic art gallery, and the cultural community was dominated by men.

Starting Out and Married Life

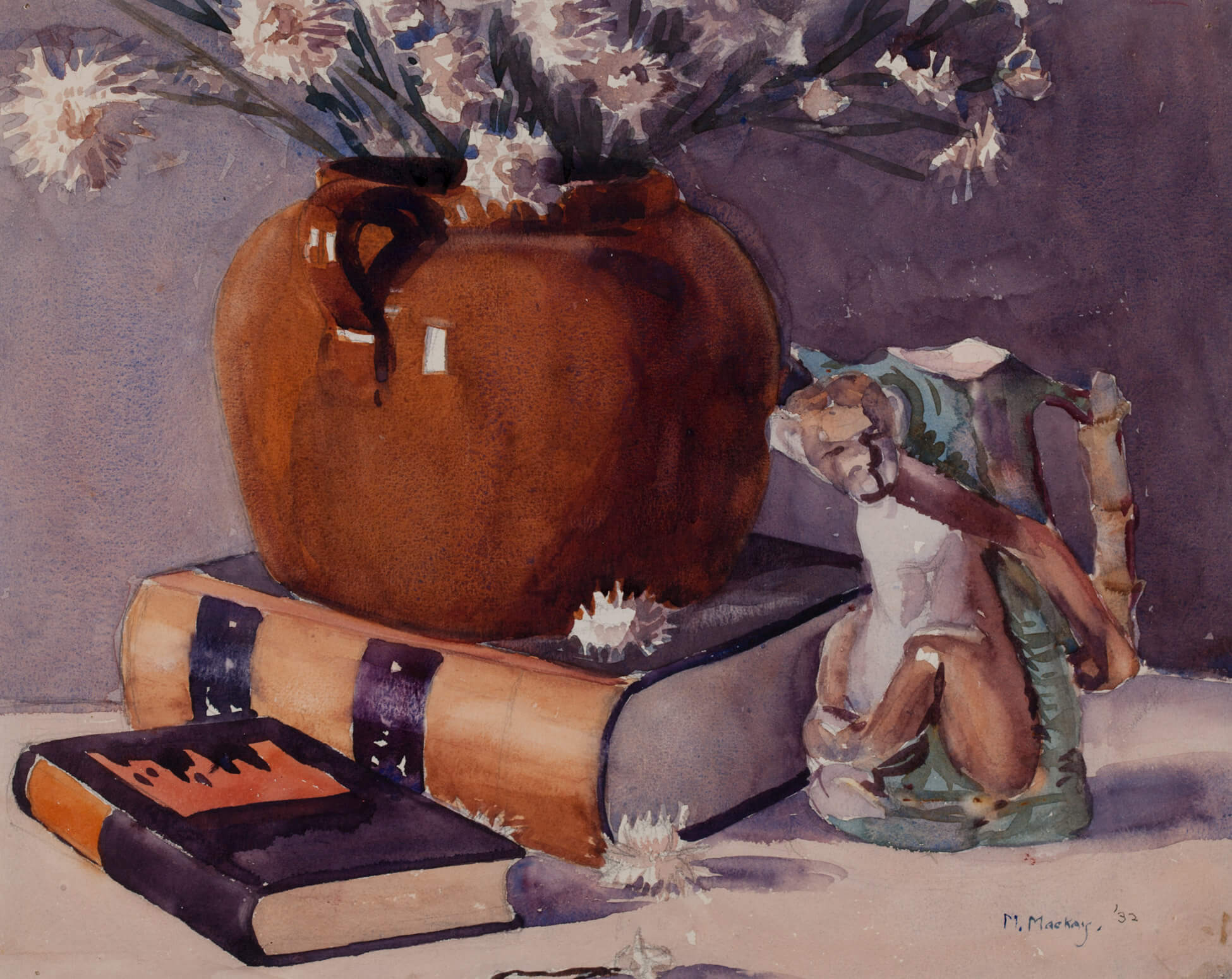

Following completion of her studies at Calgary’s Provincial Institute of Technology and Art (PITA), Marion participated in the plein air summer classes led by A. C. Leighton at Seebe, Canmore, and Kananaskis, Alberta (1932, 1933, and 1934). During these years, she was creating naturalistic compositions, such as Flowers, Vase, Books, and Porcelain, 1932, and Summer Rain, 1934.

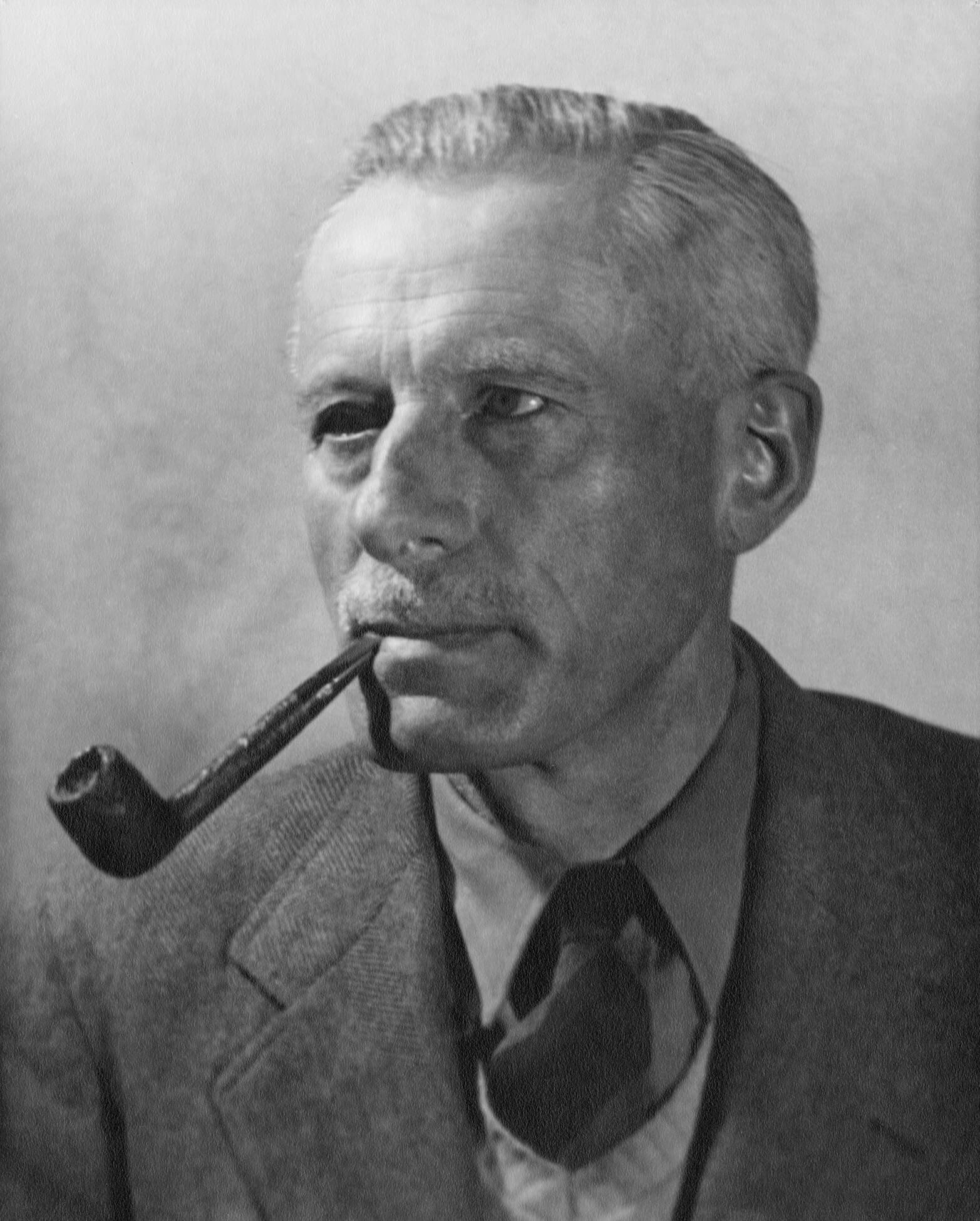

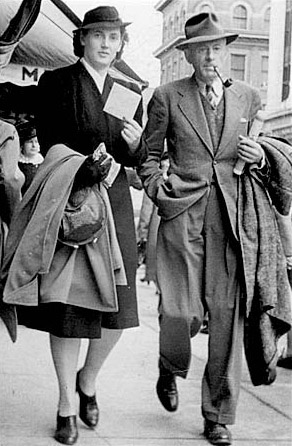

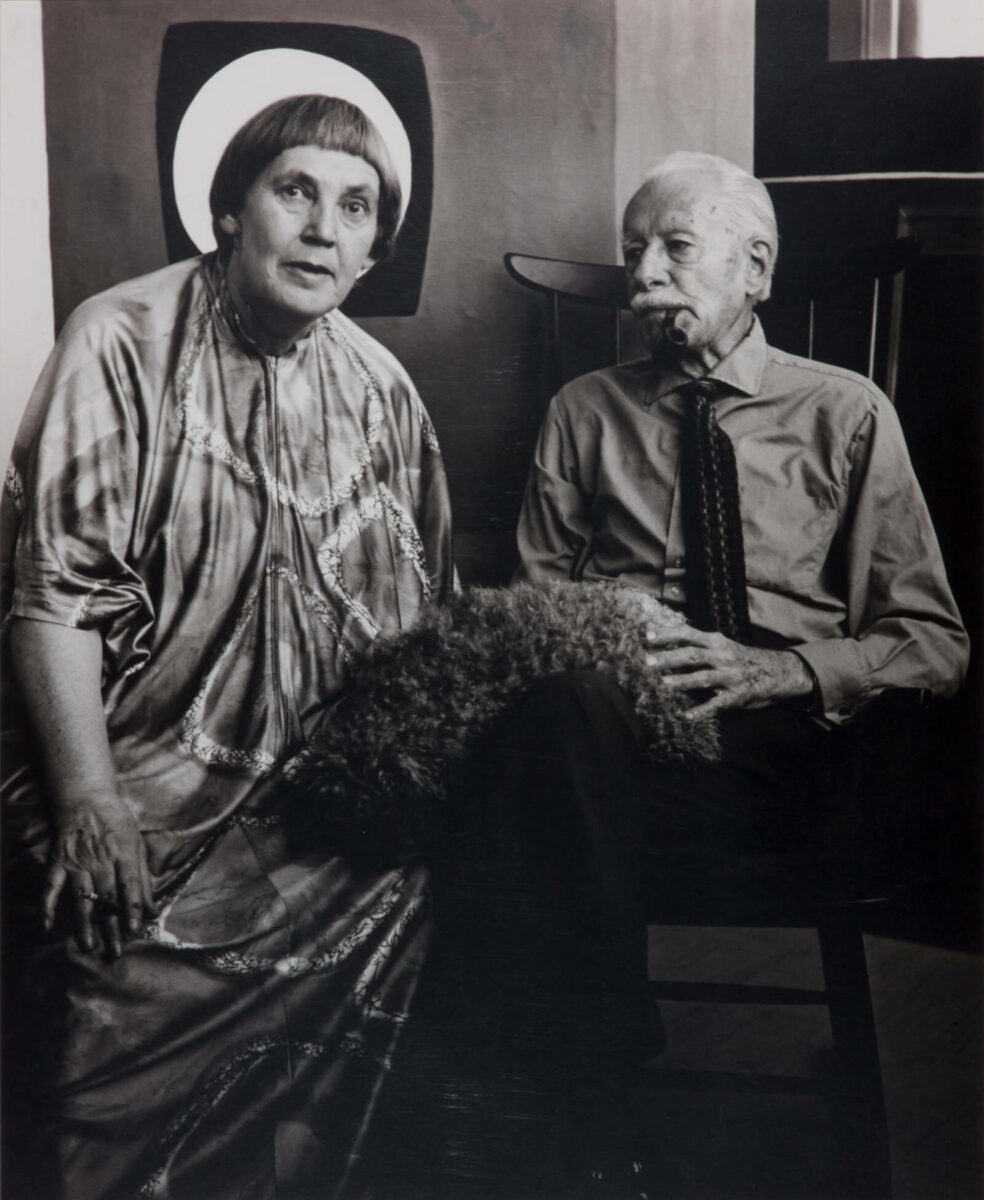

At the Calgary Sketch Club in 1931, Marion met fellow painter James (Jim) McLaren Nicoll (1892–1986), a First World War veteran with interests in art and poetry who had achieved the rank of Sergeant and was recipient of a Medal of Bravery. He earned a living surveying land after graduating from Civil Engineering at the University of Alberta in 1924, and his drafting skills informed his naturalistic aesthetic. After a long engagement, they married in September 1940 in Medicine Hat, Alberta.

Jim Nicoll was seventeen years Marion’s senior. By 1933, their relationship was serious—and long-distance, since his work for oil companies took him across Canada while she remained in Calgary. His Portrait of Marion, 1935, expresses his affection for her as artist’s muse. She is presented at age twenty-six, and her piercing brown eyes are keenly aware of him. The work depicts her cheekbones deeply shadowed, her brows thick, and her lips carefully contoured.

This flattering image contradicts how Marion felt about herself then, struggling as she was to be comfortable in her atypically tall female body. From Turner Valley, Alberta, where she was sketching at the time, she wrote, “I’ve slipped back lamentably. A woman is a poor weak thing—even a six foot one… I’ve just eaten a stupendous meal with the greatest of ease. You’ll probably fall out of love with me when you see my so-called figure.” It would be years yet before she shed the deference and feminine norms that shaped her identity as a young person during the early years of her companionship with Nicoll, and it was her artistic journey that propelled her forward.

Marion’s instructors, Leighton and Reginald Llewellyn Harvey, established the Alberta Society of Artists in 1931, which aimed to foster and promote the development of fine arts through member communications, exhibitions, and clubs. Marion was elected an associate in 1936 and “remained only an associate until the category was eliminated in 1954”; meanwhile, her male counterparts were given full membership status from the start. It was in response to such discrimination that she joined the Women Sketch Hunters of Alberta in 1935, a collective of about ten women—other members included Annora Brown and Ella May Walker (1892–1960)—who exhibited together in defiance of male control over exhibitions.

A boost of confidence came in 1936, when Mountain Water, c.1936, was accepted in the Exhibition of Contemporary Canadian Painting at the National Gallery of Canada, which circulated to South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and Hawaii. Afterwards, when it was presented in Toronto at the Canadian National Exhibition in 1939, a reviewer described it as “successfully giving the feeling of a turbulent mountain stream tumbling among the rocks.” With its harmonious earth-tone palette, loose brushwork, and close-up composition, the painting exemplifies the artist’s evolving style.

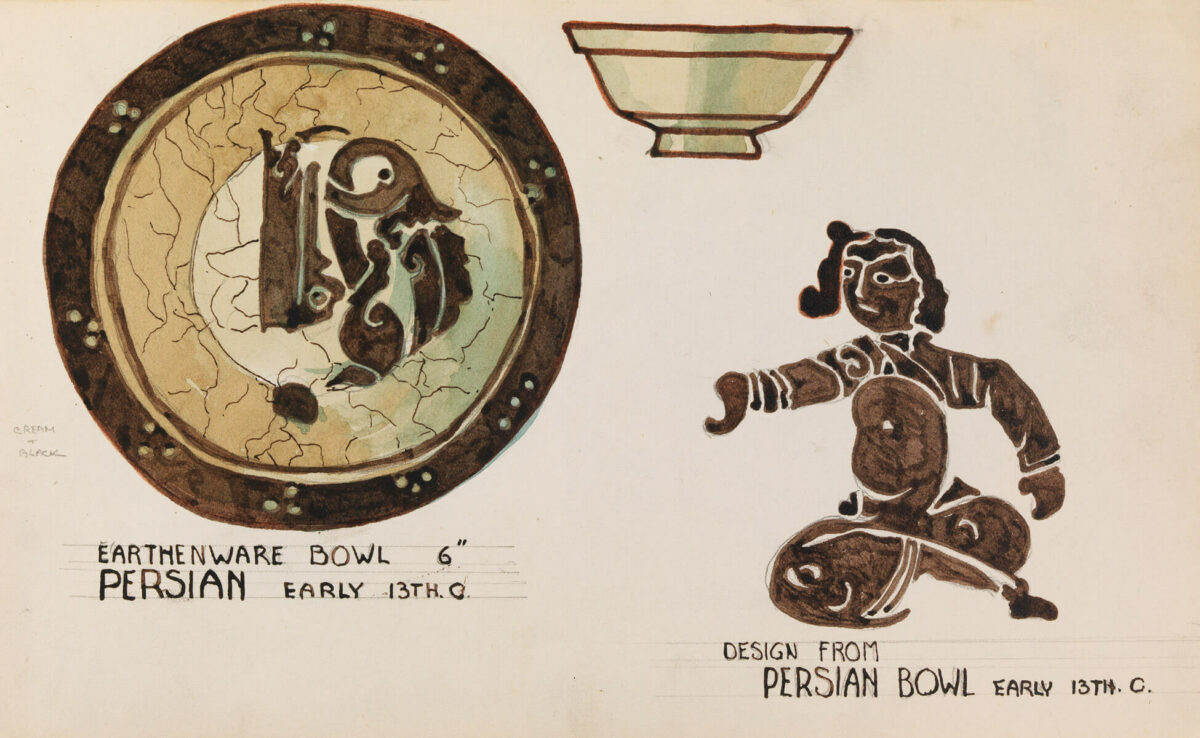

Since her appointment as instructor at PITA in 1935, Marion had been teaching design and crafts, subjects in which she had limited formal education. Pragmatically, to remain competitive in a male-centered workplace, she decided to study at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, in London, England (now Central Saint Martins), where her skills in decorative arts and art history were strengthened. Faculty there included painter and textile designer Bernard Adeney (1878–1966), German print scholar Sir Sydney Carlyle Cockerell (1867–1962), potter and textile artist Dora Billington (1890–1968), and Bloomsbury Group painter and designer Duncan Grant (1885–1978). Time at London’s National Gallery, the British Museum, and the Tate Gallery, and travels to museums in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark gave her further appreciation of world cultures. Her sketchbooks from her time in Europe include drawings of places she visited as well as of ancient pottery.

In December 1937, Marion’s mother passed away but, with her father’s encouragement, she stayed in London to complete her coursework. On June 18, 1938, she returned to Canada and she resumed teaching at PITA in the fall. With her new skills, the technical programs grew to include fabric decoration, batik, leather, block printing, and silkscreen printing. She remained in her position until she married and, amid the Second World War (1939–1945), the next six years proved challenging.

Getting married and becoming Marion Nicoll suspended her regular teaching income and public life, for which she offered this brief explanation: “The writer married in 1940 and left the school.” Implemented widely throughout the Western world, the Marriage Bar was a practice that discriminated against women’s employment after marriage and it may have been the reason for her departure from teaching. As well, Jim Nicoll’s transfers with the Royal Canadian Air Force led to sixteen relocations in the first three years of their life together.

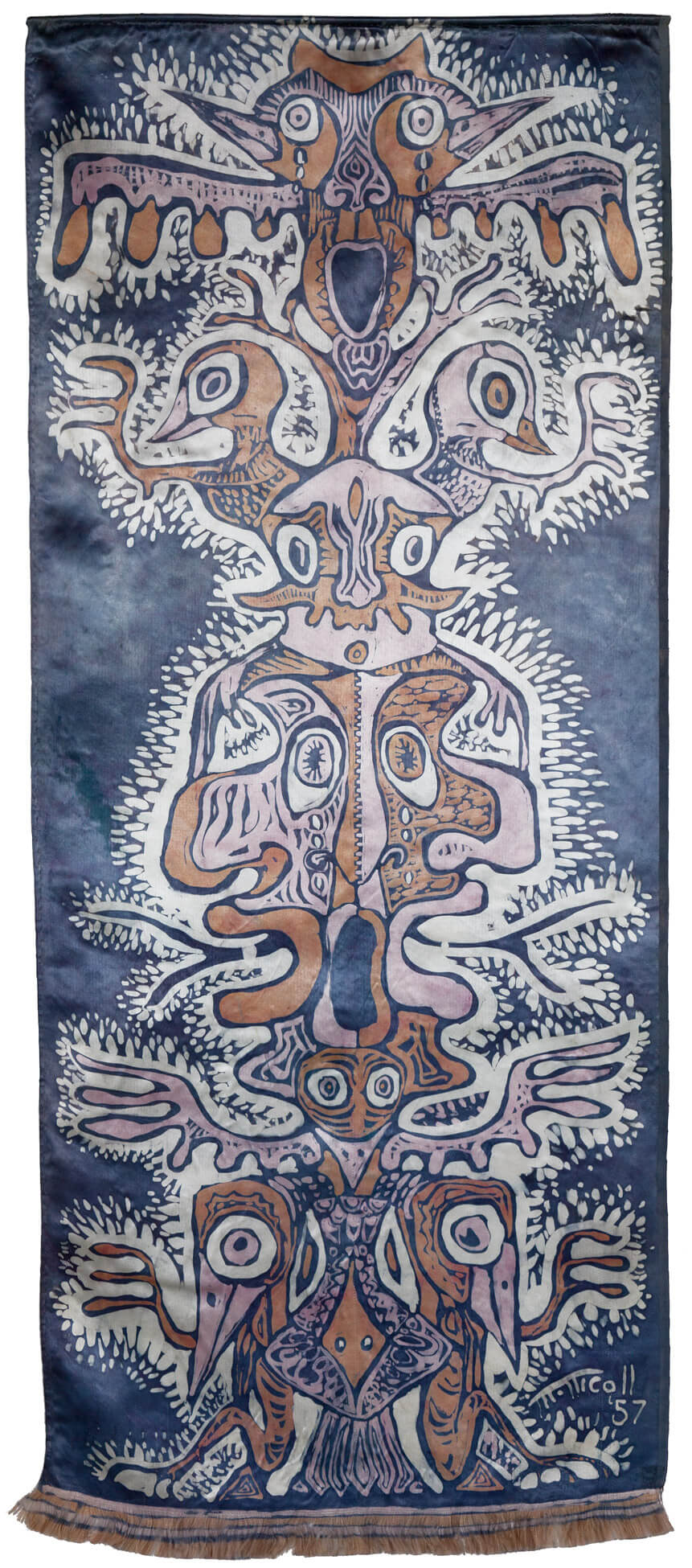

Jim Nicoll’s Interior (Marion on Stairway), 1942, shows his wife perched atop a stairwell, casting an ominous, double-life-size shadow on the far wall. The grim expression she wears suggests a discontent with domestic life. However, the couple continued to share a vision for Calgary’s artistic evolution as Jim became more involved with the Alberta Society of Artists, serving as editor of its Highlights magazine in 1942 and as president in 1943. It was not until 1945, after the couple settled in Bowness, West Calgary, that Nicoll found another teaching opportunity, at the Central Alberta Sanitorium. Throughout the next decade, she became a respected educator and an expert in batik. It was also at this time that she became Alberta’s only artist working in automatism.

Experimentation and Teaching

In 1946, Marion Nicoll was hired as the only female teacher at the Banff School of Fine Arts summer program. Faculty included Jock Macdonald (1897–1960), who had also just been appointed Head of the Art Department at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art (PITA); it was probably under his leadership that Nicoll rejoined the organization in 1947 as Instructor in the School of Crafts. This position was pivotal to her work in the 1950s, as she became known for her classes in design, printmaking, textile arts, leatherwork, and jewelry making. She was nationally admired for her batiks, and her pins, pendants, earrings, and rings were featured in touring exhibitions.

Nicoll and Macdonald only worked together for a short time. Twenty years after Maxwell Bates (1906–1980) and William Stevenson (1905–1966) had been banned from Calgary Art Association exhibitions for showing paintings that were “too modern,” Macdonald left “to escape Calgary’s isolation, the lack of understanding about art in general, and the environment of the school itself.” Despite his decision to relocate to Toronto in 1947, the brief period that he and Nicoll were colleagues proved crucial: he introduced her to automatism as practiced by the European Surrealists, a method he had been exploring in watercolours such as Fish Playground, 1946.

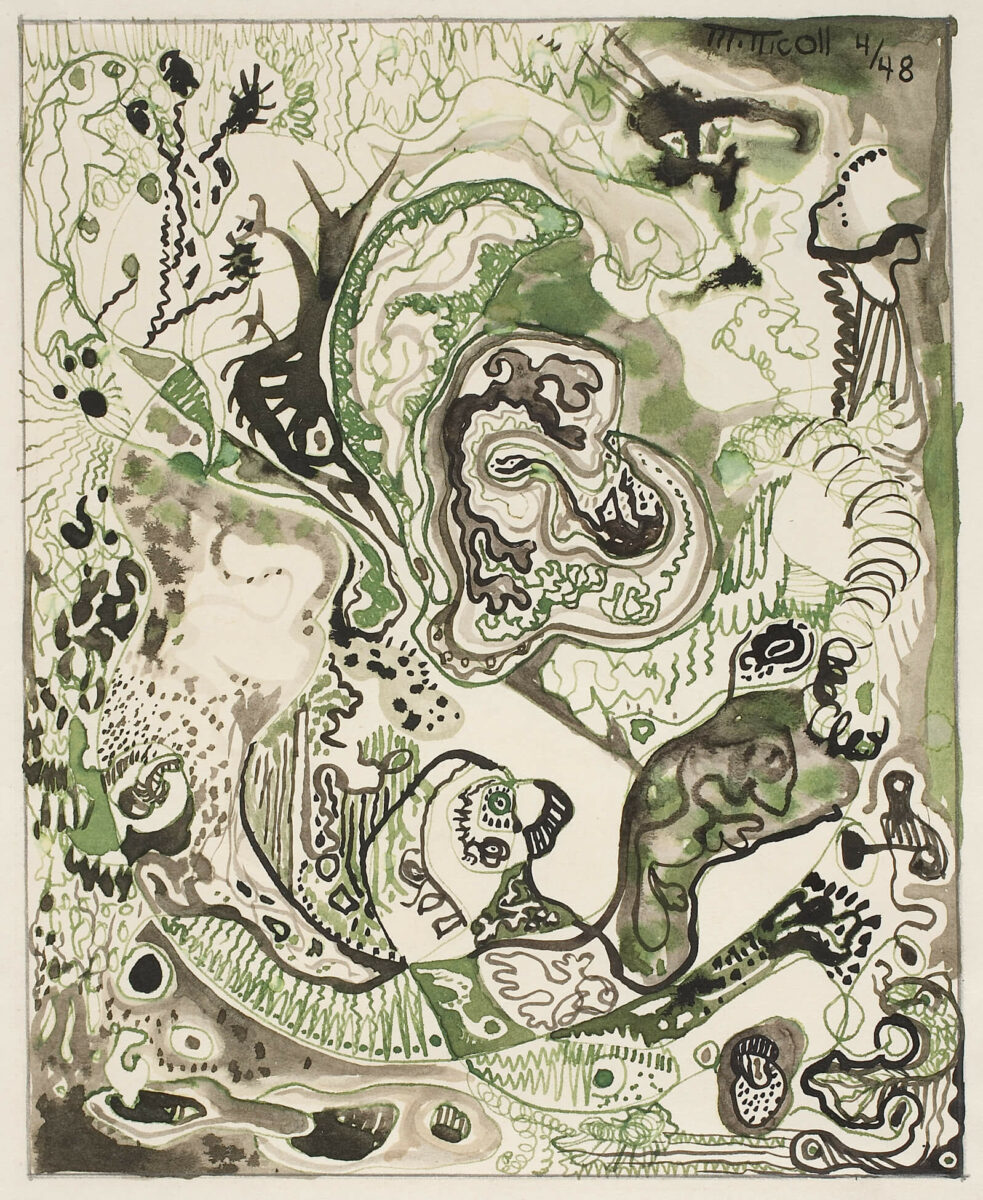

Working automatically involved allowing the hand and pencil, brush, and colour to move without premeditation. Nicoll was so excited that she filled four-foot high stacks of sketchbooks for the next six years—two compositions known as Untitled (Automatic Drawing), both 1948, exemplify her efforts. In her automatics, her process involved two steps: turn inward to her imagination, and then materialize her imagery in painting or drawing. She found the experience of accessing her inner world of symbols and forgotten memories so rejuvenating that, she explained, “Doing one is like having a two-hour nap.” Inspired by the theories of modern psychologist Carl Jung, in her reflections on automatism Nicoll noted, “It was an inside source that you gathered from outside and it was at your subconscious level and the automatic drawing brought it out. That all the impressions that you have of things, through your eyes, through your senses all gather there and it is…nothing that you’ve seen or touched or smelt [sic] is lost, it’s all sorted in the subconscious…I did things that really shocked me…Violent and peculiar and men or women or creatures with both male and female organs, birds with long forked tongues….I did childhood memories that I’d forgotten all about.”

After Macdonald left Alberta, Nicoll worked alone in automatism, far removed from Montreal’s Automatiste movement, which she followed through art periodicals. She continued reading Jungian psychology, including British author Percival William Martin’s Experiment in Depth: A Study in the Work of Jung, Eliot and Toynbee (1955). Martin entreated the individual citizen to lead a balanced life by engaging in a process of withdrawal (turning inward to spirit and faith) and return (back to the material, physical world). Balance, he argued, included relationships between the inner and outer self, the individual and society, eternity and time, and the physical and social sciences. He called for a fellowship of humanity in the wake of the atomic bomb deployment against Japan in 1945.

Nicoll embraced Experiment in Depth as a tool for “self analysis” and by the time this work entered her library, she was already well practiced at the three steps Martin recommended: in her landscapes she was practiced in communion with nature, and in her automatics she was practiced in tracking and recording her dreams and then painting and drawing from the unconscious. By the mid-1950s, Nicoll had solidified the process of visualizing ideas from her inner imagination in art but, because she considered her automatics private and not for exhibition, her “return” to the outer world as a public abstractionist would not take place until 1959.

Instead of submitting her abstract work to society-painting exhibitions, Nicoll took a different approach by infusing automatism into her batiks, prints, and landscapes and making those public instead. For instance, mythical sea creatures float in space and are surrounded by sinuous lines in her batik Fishes, 1955, exhibited at Coste House, Calgary, in 1957. Nicoll’s batik scarves were also worn by her collectors. The print Bird Pattern, 1950, derived from one of her automatics, was the cover image of Highlights magazine for an entire year.

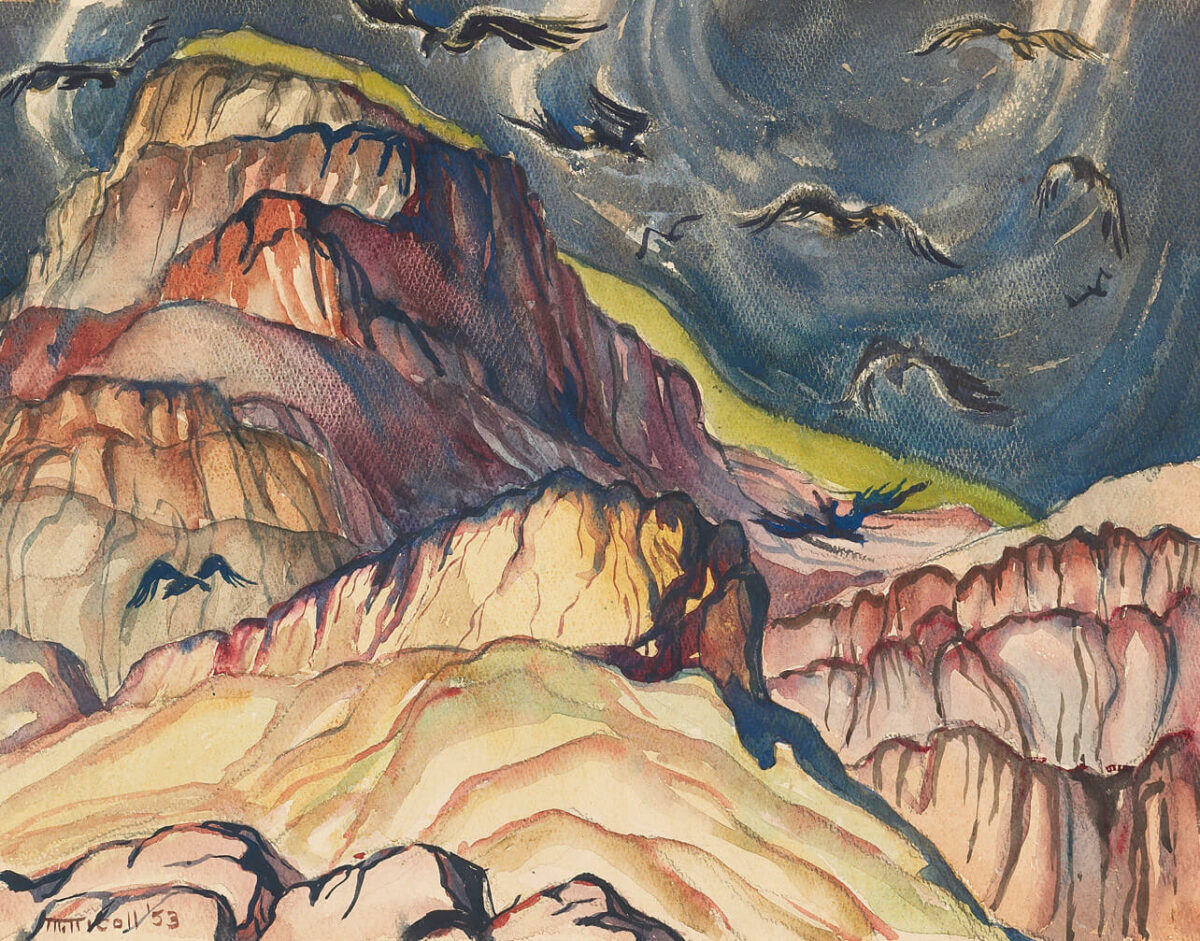

Nicoll’s few landscapes of the 1950s are not simple records of nature but rather amplifications of mood and imagination. In Badlands, Eladesor, 1953, a flock of birds swoops in from a dark sky over a desolate, dry landscape, as though a prelude to Alfred Hitchcock’s film The Birds (1963). The sombre Graveyard and Hoodoos, 1955, contrasts the brevity of life against the power of nature’s weatherworn ancient hoodoos. August Heat, 1957, conveys a scorching day where even the trees, contoured with vibrating yellow, appear to shake with heat stress.

New York and Europe

Between 1957 and 1959, Marion Nicoll made a momentous transition in her painting, spurred by her attendance at the 1957 Emma Lake Artists’ Workshops, north of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. American artist Will Barnet (1911–2012), who had been working as official printer for the Art Students League of New York since 1934, was engaged to lead that year’s session, and Nicoll had expected to study printmaking with him—she was experimenting with the medium at the time—but when the necessary supplies were not delivered, Barnet elected to switch the focus to painting and he brought in an Indigenous model to pose for the group. For Nicoll, his approach to teaching was motivating, and she later remembered, “I took off on the first day.”

Little Indian Girl, 1957–58, shows Nicoll’s simplification of shapes and patterns, use of bold colours, and experimentation with black outline. The figure, now the point of departure, added a third step to her abstractions as compared to the automatics: first, observe the external world; second, distill and simplify the sights seen through inner imagination; and third, paint these forms.

At Emma Lake her painting was forever changed, and she announced to her husband, “We are going to New York and that’s that.” In summer 1958, Nicoll arranged a self-financed leave from teaching from the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art (PITA) and she and Jim Nicoll (now retired) left for the Art Students League, where she continued to work with Barnet. Two years her junior, Barnet was ultimately a colleague and a lifelong friend more than he was a teacher to her.

Through Barnet, Nicoll met key figures in the New York art world, such as Robert Beverly Hale, curator of American painting and sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the legendary critic Clement Greenberg (1909–1994). The Nicolls visited museums and commercial galleries including the Metropolitan Museum, the Frick Collection, and Bertha Schaefer Gallery of Contemporary Art, and she respected paintings by Mark Rothko (1903–1970), Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), and Hans Hofmann (1880–1966).

Two of Nicoll’s responses to the New York cityscape, East River, 1958, and The Beautiful City, 1959, illustrate the move she made from naturalism to hard-edge painting while living in Manhattan. East River remains governed by illusionistic perspective, whereas The Beautiful City is a flat field of contrasting light and dark with crisply separated areas of colour and shape, the subject not recognizable, even with a title. The transition had been intense. To her artist friend Janet Mitchell (1912–1998) she wrote, “You know my hunger to paint has been insatiable—it’s been a strange time, thinking, feeling, sleeping, eating, painting…I think I’ve whipped my tendency to be decorative—at least to the extent of recognizing it when it happens. Isn’t it odd that the training I’ve had has become an obstacle to be jumped before I could paint?” She would later describe her new works as “classical abstractions.”

The quality of Nicoll’s painting led to three teaching offers, including one at Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. When painter Will Barnet (1911–2012) encouraged her to stay in New York, she wrote to Mitchell, “It’s wonderful to have people consider you a serious painter. Calgary has beaten me down pretty badly.” Unfortunately, Jim did not share her enthusiasm for the city, which she summarized thus: “I love New York. My husband doesn’t.” Nicoll turned down the job offers but forged ahead with abstraction while Jim’s work remained entrenched in naturalism. Although they remained married for life, at this point their paths as artists separated for good.

Peer recognition from home soon followed when Nicoll received confirmation of her first Canada Council grant. This boost to the summer ahead deferred an immediate return to Alberta. Nicoll said, “If I had to return to Calgary straight from here instead of having the glow of Italy in front of me I’d cut my throat and bleed messily from here to Times Square.” It was time to recuperate from an intense year and become acquainted with southwestern Europe and their favorite Italian and Spanish artists: Giotto (1266/67–1337), Cimabue (1240–1302), El Greco (c.1541–1614), and Francisco Goya (1746–1828).

In May 1959, the Nicolls arrived at the island of Sicily, where Marion’s response to the Mediterranean climate and ancient architectural ruins of Giardini Naxos and Taormina spawned a new body of work. She remembered “the deep, dark purple lava rock from [volcanic Mount] Etna….The only people near you from the beach were the lemon orchard workers.…It’s a gorgeous place. You could just feel yourself letting go.” Their landlord’s house became the point of departure for one of Nicoll’s most important paintings, Sicilia V: The House of Padrone, 1959, a work that was one of Nicoll’s earliest successes in rethinking the relationship of colour and shape. She explained, “Colour for me is a shape and a shape is a colour—one demands the other.”

Nicoll had always been aware of her environment, but now it propelled her abstract production. The Nicolls’ travels in Italy included Rome, where she began Rome I: The Shape of the Night, 1960, a daring combination of iridescent blues and pinks balanced against black and green. They spent time in Spain and Portugal before their return to Canada in late August 1959. Nicoll shipped her unfinished European works back to Calgary and summarized her year away as “a vital one in my development as a painter.”

Homecoming

After several months in Europe, Nicoll returned to Calgary with new confidence in 1959. She resumed teaching at the Alberta College of Art, and in December she opened a solo exhibition featuring twenty artworks from her time in New York and Sicily. The event officially launched her reputation as an abstract painter. The show included Thursday’s Model, Spring, and The Beautiful City, all 1959. Abstraction was slowly becoming more accepted in Alberta throughout the 1950s and a month before Nicoll’s exhibition, her teaching colleagues Stanford Blodgett (1909–2006) and James Stanford Perrott (1917–2001) held an expressionist art show.

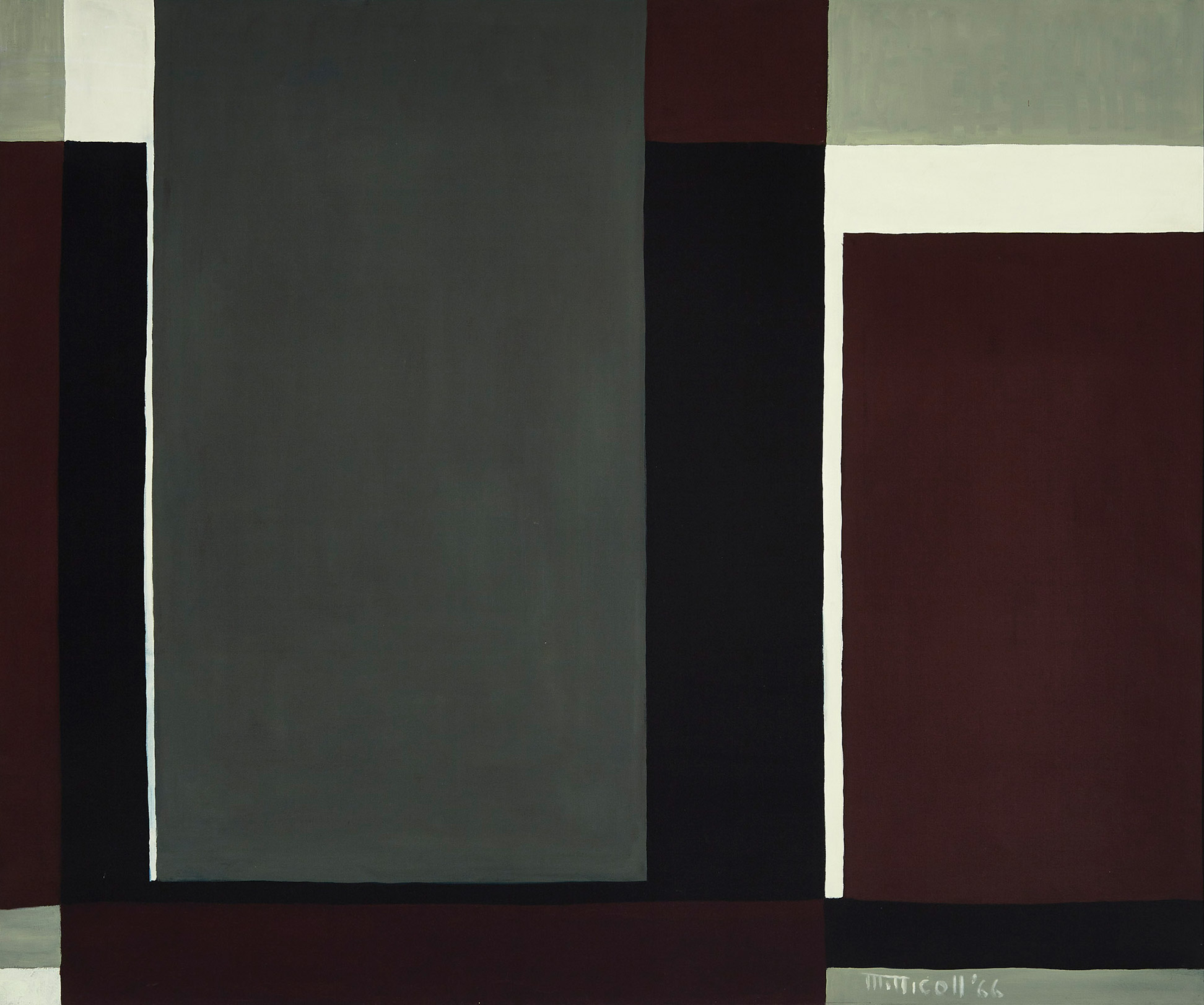

The response to Nicoll’s exhibition was generally positive, noting her work’s austerity, clarity, economy of means, and “pure aesthetic reality.” Among her female circle, painters who embraced fantasy and abstraction included Janet Mitchell, Helen Stadelbauer (1910–2006), and Ella May Walker. Unlike her peers, however, Nicoll never returned to naturalism. She described her distinct approach by saying, “I evolved my own way into a sharp edged painter, no gradations, no muddiness, no muddy colour…I don’t fuzz off the edges.”

After the heady days of life in New York, Nicoll remained conflicted about returning to conservative Calgary. Nonetheless, her home city inspired paintings such as The City on Sunday, 1960, City Lights, 1962, Bowness Road, 2 AM, 1963, and the Calgary Series (I–III), 1964–66.

Nicoll’s almost boundless production from this period led to significant critical attention. In summer 1962, Clement Greenberg visited her during his art tour of the Canadian Prairies, and a year later he identified “Nicoll as among the best painters in oil and watercolour to hail from Calgary” in an article for Canadian Art magazine. She was included in the National Gallery of Canada’s 5th Biennial Exhibition of Canadian Painting 1963, wherein she was one of only eight female artists of the total seventy-eight. This show opened in London, England, and toured Canada from Quebec to the West Coast afterwards. Exhibition curator J. Russell Harper positioned Nicoll as among the important experimental artists working in the Prairies. A second solo exhibition in Calgary followed.

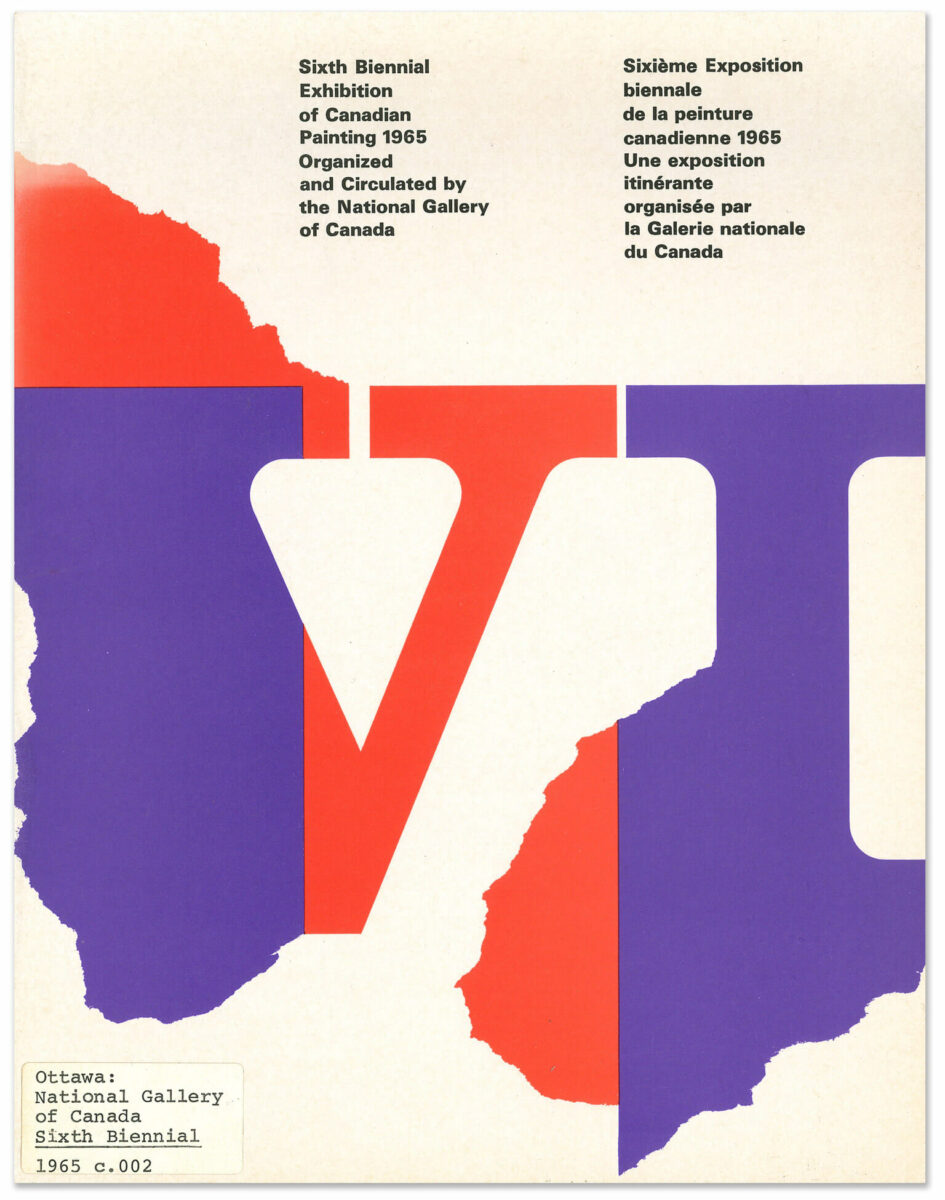

Nicoll’s importance was further solidified when her solo show organized by the Western Canadian Art Circuit toured to six venues between 1965 and 1966. She participated in the Sixth Biennial Exhibition of Canadian Painting 1965, curated by former Western Canadian artist and then Slade School of Art professor William Townsend (1909–1973), and that exhibition gave credence to Nicoll’s place in the canon of important contemporary Canadian painting.

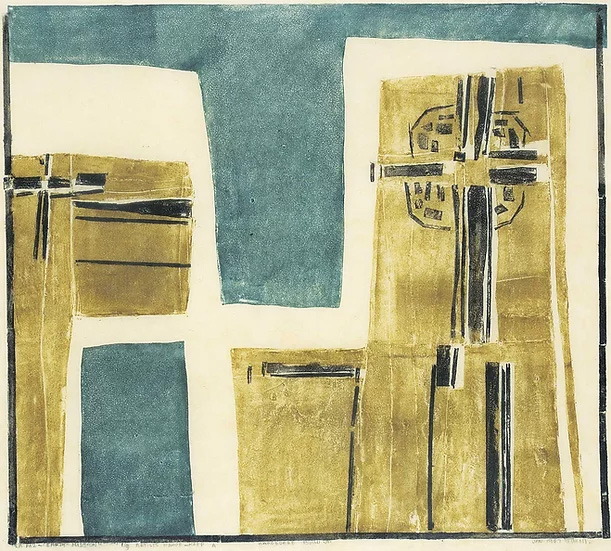

In 1960, she had renewed her interest in printmaking, and several of her prints were extensions from her painting practice, such as Waiting, 1965. These prints garnered further interest from local, territorial, and national graphic arts exhibitions, including the annual Calgary Graphics exhibits (1963 through 1967), the Centennial Exhibition of Western Printmakers, which toured to thirteen venues (1967–1968), and the Canadian Society of Graphic Art (1968).

Recognition in North America and Britain through exhibitions and publications was a significant boost to Nicoll’s self-confidence and evolution as an artist and person, but the change had not happened overnight. In 1953, she presented herself thus to a reviewer: “The winter garb of this Calgary-born artist consists of a chain girdled red-gold smock with a Persian pattern, a green tartan shirt, and ski slacks. Her head is covered with a French beret and her feet shod in high buckskin moccasins embroidered by the Indians of the Sarcee reserve.” By 1963, student Pat Kemball (later known as ManWoman [1938–2012]) remembered her thus: “She had a soup bowl haircut, wore large moomoos (a loose dress from Hawaii), and smoked cigars, she scared the hell out of the first-year students.” The affectionate side of Nicoll, whose union to Jim Nicoll was childless, included her love of animals: at one time the Bowness household included four cats and a dog.

Nicoll was a dear friend to many artists, including Jock Macdonald, Janet Mitchell, and Will Barnet, but was happiest alone in her studio making art, away from the limelight. Her husband’s watercolour Solitaire, painted when she was a young woman, had taken note of Nicoll’s ability to entertain herself with a solo card game, with no need for another player. He often participated on boards and juries, leaving Nicoll with precious time and privacy to create. Reluctant to accept interviews, she asserted, “If I had my own way I wouldn’t even talk. Words fall so short of what a person is trying to paint. If you could describe your feelings with words, you would write instead of paint.”

As these observations illustrate, in her senior years Nicoll grew to care less and less about how others perceived her in appearance and she performed her gender with some degree of wit. By the end of the 1960s, it was clear that she was an artistic force, assured and comfortable in her own skin, unconcerned with the gender norms that had once governed her female self. Had Nicoll been able to benefit from the writings of theorist Judith Butler, she may well have agreed with her evolving concept of gender identity: “The body is not understood as a static and accomplished fact, but as an aging process, a mode of becoming that…exceeds the norm, reworks the norm, and makes us see how realities to which we thought we were confined are not written in stone.”

Retirement and Legacy

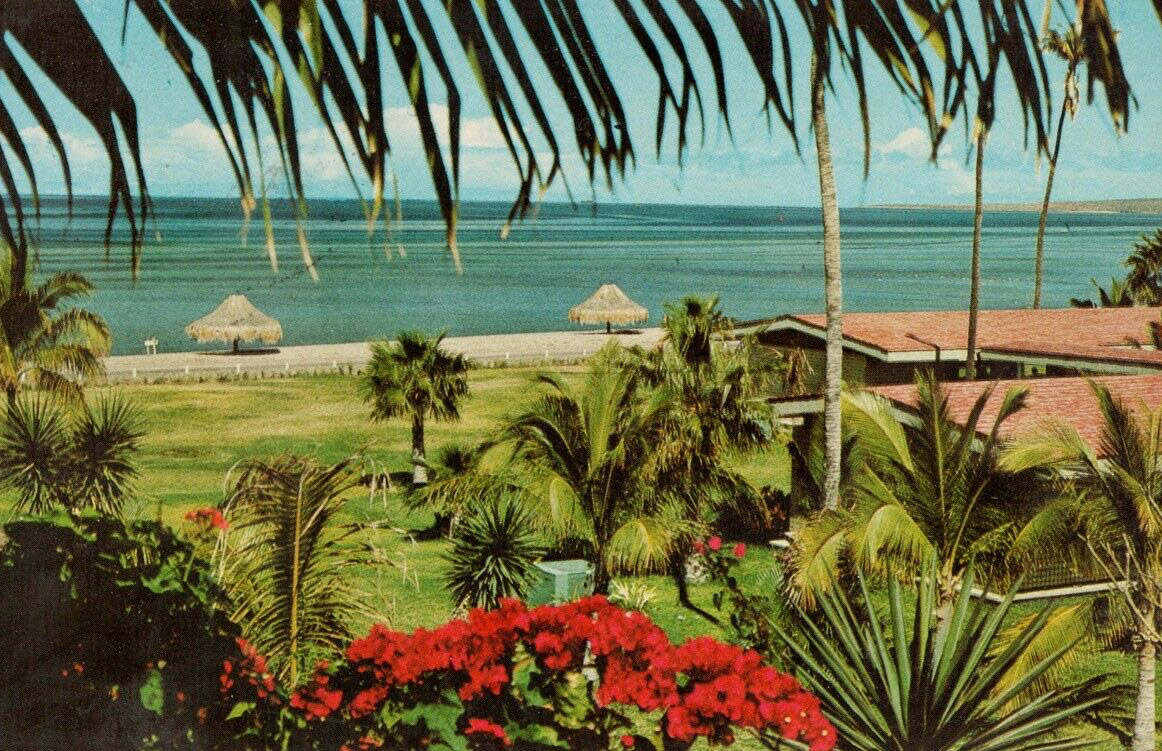

Nicoll had longed to focus full-time on her art since returning from New York in 1959. To realize that goal, she resigned from teaching at the Alberta College of Art on January 31, 1966, at age fifty-seven. The decision enabled her to establish a new schedule of priorities and she continued to be honoured with recognition. That winter, her sister-in-law gifted her a holiday in La Paz, Mexico, as reprieve from the cold Alberta winter that so troubled her rheumatoid arthritis.

It was in Mexico that Nicoll learned the news of her second endorsement from the Canada Council for the Arts, this time a Senior Artist Fellowship. She wrote to her liaison officer, “I was lying like a fat toad, on a deck chair in the garden patio of Guaycura Hotel under a leafless primavera tree, with its clouds of pink blossoms, and buzzing with the big black bumblebees. I read it twice and said: ‘Jesus, a Margarita please.’”

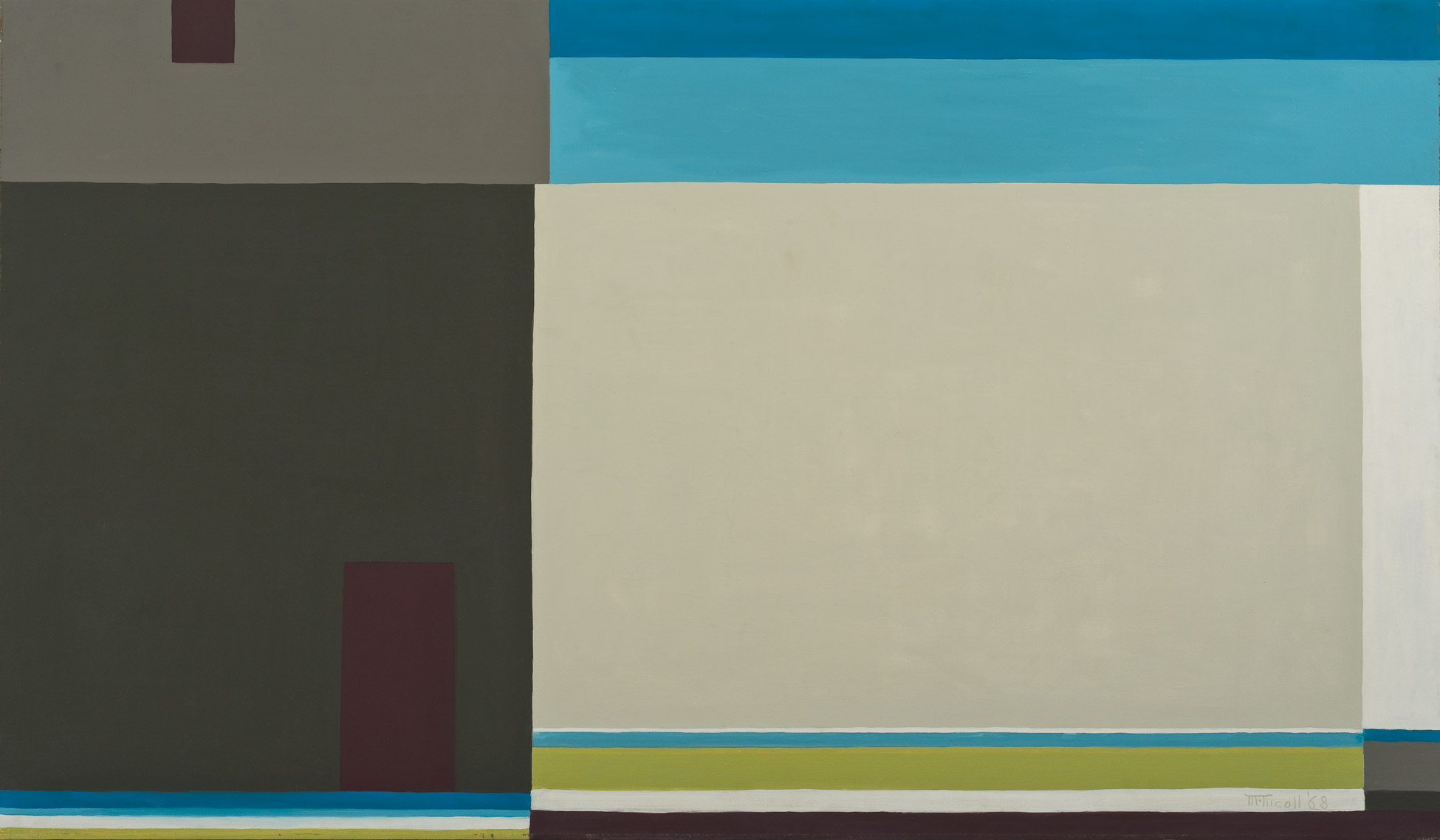

She returned to Calgary in mid-March. For that year, she refrained from the heavy exhibition schedule she had been sustaining to prioritize making new work. In late October, she took a six-week trip to Ottawa, Montreal, and Toronto to meet dealers and curators to begin planning new exhibitions. Between 1966 and 1968, she finished the Calgary Series, developed the Guaycura (I–II) and Runes (I–II) Series, and created single paintings, such as Prairie Farm, 1968.

Nicoll’s late works show her moving to even stricter and minimal geometries. Inclusion in J. Russell Harper’s 1966 monumental Painting in Canada: A History was further affirmation of her place in the emerging canon of Canadian art history. Mexico provided source material for her prints and paintings in the Guaycura and La Paz series, and January ’68, 1968, was included in the last of the National Gallery of Canada’s biennial exhibitions of Canadian painting. She further enjoyed commercial successes with gallerists Henry Bonli in Toronto in 1967 and Vincent Price Gallery in Chicago in 1968. Six prints, including Northern Nesting Grounds, 1964, were shown in the survey exhibitions Directions in Western Canadian Printmaking (Winnipeg Art Gallery, 1968) and Canadian Printmakers Showcase (Carleton University, 1969).

Nicoll’s decision to build a career as an abstract artist through her hard-edge oil and acrylic paintings—as opposed to through her automatic watercolours, which she largely regarded as private—was significant. Her preoccupation with time through strategic titling was to underscore the vital role nature plays in leading a balanced life of faith and humanity in a troubled world. Calgary III, 4 AM, 1966, The City on Sunday, 1960, Spring, 1959, and End of Summer, 1963, take note of precise hours, days of the week, seasons, and ephemeral phenomena. The triptych Journey to the Mountains: Approach, The Mountains, Return, 1968–69, expressed time sequentially through travel. Nicoll took stock of a full year in the four-panel One Year, 1971.

Despite working against the ticking clock of advancing arthritis, Nicoll’s last decade revealed a life of inner calm and order, distilled from an outer world in which she had always found beauty, despite having lived through two world wars and in a nuclear age of virtually unchecked scientific advancement, almost to humanity’s peril. Her last major work, One Year, was her final reminder of the life cycle as she closed down her painter’s practice that same year, no longer able to stand before her easel. She was just sixty-three and had only recently found the voice she had so long searched for.

Nicoll’s creative legacy was her final project. In 1972, she organized a commercial retrospective exhibition of thirty-six prints surveying her abstract print practice from 1960 to 1972. She and her husband made plans that the Alberta Art Foundation would be their beneficiary. Her first retrospective exhibition organized by a public art gallery in 1975, which featured major works such as Rome I: The Shape of the Night, 1960, Ancient Wall, 1962, and Bowness Road, 2 AM, 1963, was curated by two of her former students, John Hall (b.1943) and Ron Moppett (b.1945), a testimony to her impact on younger artists.

In 1977, Nicoll became the first female artist in the Prairies to become a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, an event that coincided with the release of the first monographic study on her life and art by J. Brooks Joyner. Her exhibition history included three artist-couple shows in which her practice far outshone Jim Nicoll’s. Her last award arrived in 1984: the Alberta Achievement Award, Excellence Category for Outstanding Contribution to Art. On March 6, 1985, Nicoll passed away at Bethany Care Centre at age seventy-five from a heart attack. She was survived by Jim, who passed the following winter.

Nicoll is remembered for her forward view of modernism in Western Canada, and as one of the most important female artists and educators of her generation. Hers was a life that offered her inner resolve as self and artist, a life finally lived in balance after a long, feminist journey of roads uneven at every turn. Her exceptional knowledge and understanding of colour theory yielded a powerful body of abstractions, which continue to delight, inform, and challenge the eye. Alberta University of the Arts professor emeritus and craft historian Jennifer Salahub has rightly observed that “We are witnessing remarkable advances in situating Nicoll’s practice within a broader Canadian social and cultural context,” but Nicoll also deserves her place in histories of abstraction, design, and arts education beyond Canada’s borders. Despite working in isolation, Calgary gave Nicoll her place in the canon of Canadian art and an enduring legacy. Her work in all media continues to be coveted today by collectors private and public.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements