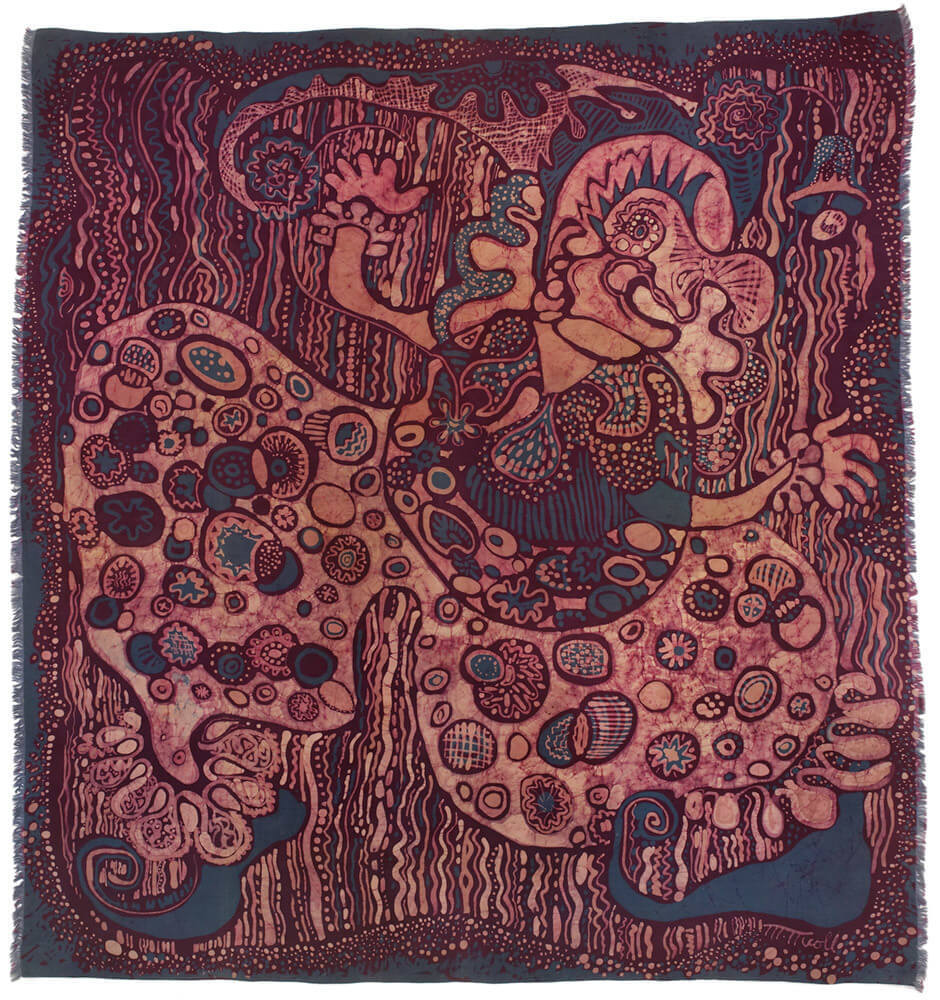

Batik c.1950

Marion Nicoll, Batik, c.1950

Aniline dye on silk, 100 x 92.5 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Marion Nicoll was first introduced to the batik process of painting on silk with wax resist when she was a student at the Ontario College of Art, Toronto. This untitled work exemplifies how she practiced automatism in her batiks by incorporating fanciful subjects and free-form organic and linear patterning. A dancing, clown-like character with decorative shoes, puffy pants, and a bird-like head crowned with a tube hat dominates the fabric area. The representational element is set against a background of repeating string-like vertical lines forming a spreading horizontal pattern. The figure’s pants are filled with ovoid and circular designs inviting interpretations ranging from seashells to bubbles and stars.

After being introduced to fabric-based work in Toronto, Nicoll continued to develop her skills under further study with ceramic and textile artists Dora Billington (1890–1968) and Duncan Grant (1885–1978) at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, London, England, in 1937–38. When she returned to an economic depression in Calgary in June 1938, her batiks became a source of income—she sold scarves through a local merchant. She also taught the ancient pre-Christian Javanese batik method in her textile classes at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art until her retirement in 1966. She explained that her batiks functioned as everything from “tapestries to wall hangings, scarves, curtains, portraits and runners.” She exhibited them as complete works of art, considering them no less significant than her work as a painter.

Nicoll was widely admired across Canada for her work as a batik artist, thanks in part to support from the Government of Alberta, which published her how-to manual Batik (1953). Her creations also earned the respect of colleague and friend Jock Macdonald (1897–1960), who asked her to teach him how to make them in summer 1951. Macdonald had introduced her to automatism a few years earlier, and decorative arts and crafts scholar Jennifer Salahub justly observes that the event represented “a reciprocal teaching moment.”

Macdonald’s regard for Nicoll’s batik work extended to the fact that this piece once found a home in his and his wife Barbara Macdonald’s personal collection. This history and provenance challenge the narrative that Nicoll’s artistic evolution was reductively comprised of a lineage of male influences. Far from it—Nicoll went on to share her knowledge with dozens of artists and students to resurrect a medium that had been cast as secondary in the contemporary art of her time, dominated as it was by painting and sculpture.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements