Anishinaabe artist Norval Morrisseau worked outside the established traditions of European visual culture and on occasion used his art to make forceful political statements. He defied categorization and challenged conventional understandings of Indigenous art. Although the media judged him harshly for his alcoholism and his traditional beliefs, such as shamanism, Morrisseau succeeded in raising awareness of Indigenous aesthetics and cultural narratives as he developed an artistic vocabulary that inspired a new Canadian art movement.

Racial Politics and Art

When Norval Morrisseau arrived on the Canadian art scene in 1962, he was something of an anomaly. At a time when enforced assimilation was national policy and First Nations had only recently been accorded the right to vote in federal elections, few Indigenous people made art that was viewed as contemporary within the narrow framework accepted in mainstream cultural circles. Most Indigenous artworks were considered artifacts, better displayed in ethnographic museums.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the federal government had invested heavily in the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, and its director, James Houston (1921–2005), worked hard to market Inuit soapstone carvings, drawings, and prints as modern artistic expressions. Canadians were being primed to consider Indigenous arts as contemporary. The Canadian Guild of Crafts also supported Indigenous arts, but its shows were typically held in venues other than art galleries. Without government intervention, there appeared to be little appetite for Indigenous art in galleries in the early 1960s.

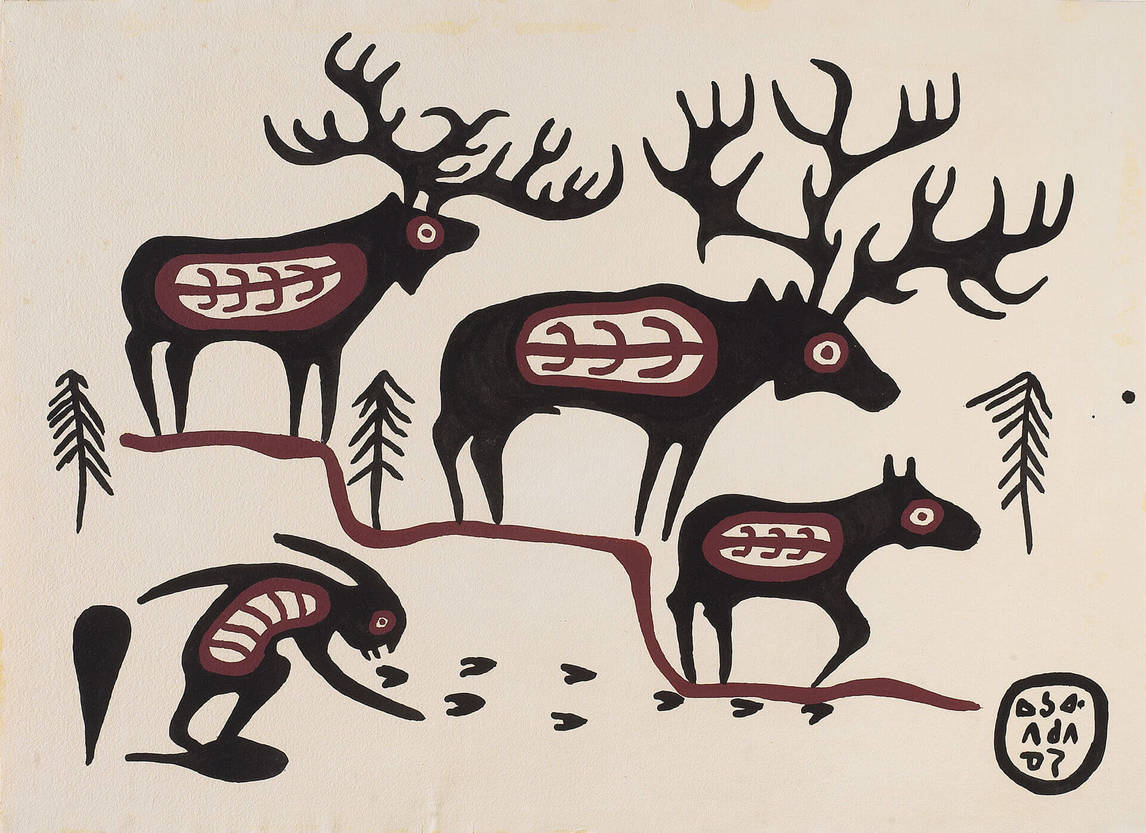

Morrisseau’s 1962 exhibition at the Pollock Gallery in Toronto therefore sparked a national news event, in part because of the artist’s racial identity and in part because he was creating contemporary art. Works like Moose Dream Legend, 1962, were hailed as both primitive and modern by critics at the time. Morrisseau’s work demonstrated clear links to the oral narrative traditions of the Anishinaabe in its process and its focus on animals and spirit-beings, but also commented on how 150 years of the assimilationist policies of Canada’s Indian Act, which included residential schooling, had visibly erased Indigenous issues and understandings from Canadian public life. Curator Gerald McMaster has described Morrisseau as “a latter-day neoprimitivist” because modern art had rejected all referents to things old or expressly cultural while it celebrated primitivism as a universal muse to the modern.

Morrisseau’s entry onto the art scene can be best described as a rupture in Canadian art history. As the civil rights movement gained momentum in the United States and inspired Native Americans to push for greater equality, and as Indigenous populations in Mexico advanced similar struggles, Canadian Indigenous peoples also organized and confronted government practices. In June 1969, the release of the Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy (a document commonly known as the 1969 White Paper) by the Trudeau government in Ottawa triggered a series of political events. These resulted in the creation of the National Indian Brotherhood and regional factions that challenged the federal government to make changes to a system that was stacked against First Nations people. Artists joined forces, too, to change the racialized ways art was being exhibited in Canada.

In 1967, Indigenous artists were commissioned to create the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67, a moment now considered pivotal in acknowledging activism and awareness of Indigenous issues in Canada, but Morrisseau left the project when the government officials organizing the exhibition deemed his mural design of bear cubs nursing from Mother Earth too controversial.

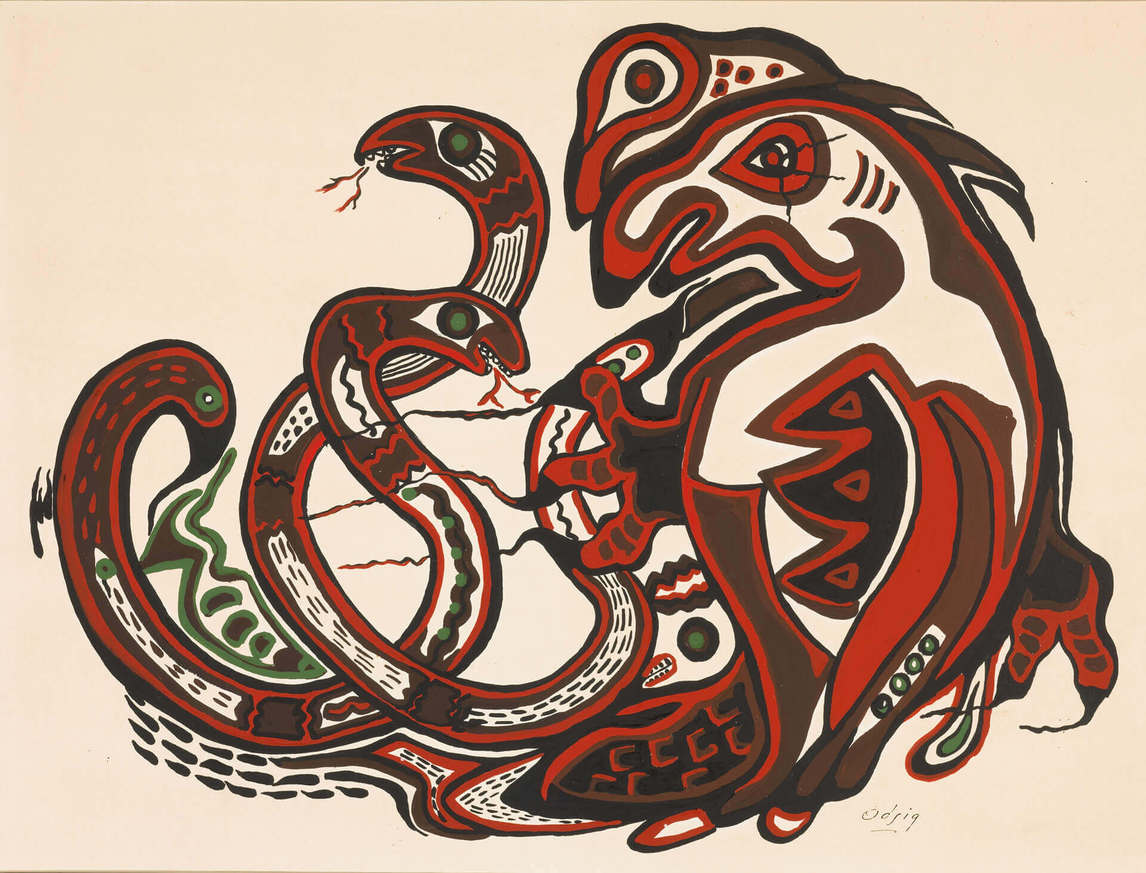

Morrisseau was part of a group called the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc., which was established by Odawa artist Daphne Odjig (b. 1919) in Winnipeg in 1973 and labelled the Indian Group of Seven by the press. Other members included Jackson Beardy (1944–1984), Alex Janvier (b. 1935), Carl Ray (1943–1978), Eddy Cobiness (1933–1996), and Joseph Sanchez (b. 1948), and its purpose was to promote Indigenous arts and foster opportunities for emerging artists.

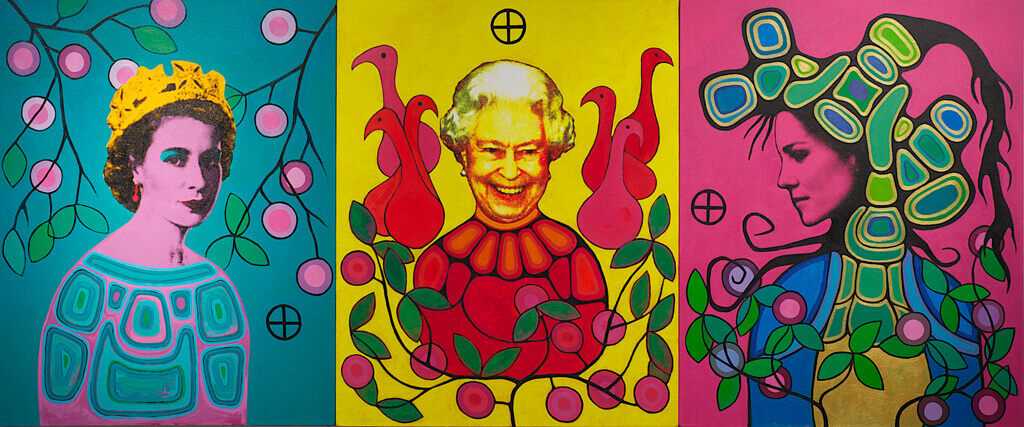

As early as 1972, anthropologist and artist Selwyn Dewdney (1909–1979) had tried to persuade the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa to add works by Morrisseau to its collection, but his effort was unsuccessful. At the time, the ethnographic Canadian Museum of Man, then in Ottawa (now the Canadian Museum of History, Hull, Quebec), was the Canadian institution that collected contemporary Indigenous art, whereas the National Gallery bought works by non-Indigenous Canadian artists. It had been more than thirty years since Dewdney’s initial request when the National Gallery of Canada purchased its first work by Norval Morrisseau. In 2006, the gallery then made him the subject of its first retrospective exhibition devoted entirely to a non-Inuit, Indigenous artist. The National Gallery of Canada mounted a retrospective exhibition of Pudlo Pudlat’s art in 1990. As art critic Paul Gessel, writing in the Ottawa Citizen, noted under the front-page headline “An Art Pioneer Makes His Final Breakthrough,” “Who would be the first Native artist to be given a show akin to the exhibitions granted such ‘white’ Canadian artists as Tom Thomson and Emily Carr? The consensus among the Aboriginal art community was that Norval Morrisseau…had to be the one.” This media coverage repositioned Morrisseau as a major Canadian artist, validated Indigenous art as contemporary, and helped end the practice of separating Indigenous from mainstream artists in public discourse.

A New Direction for Indigenous Art

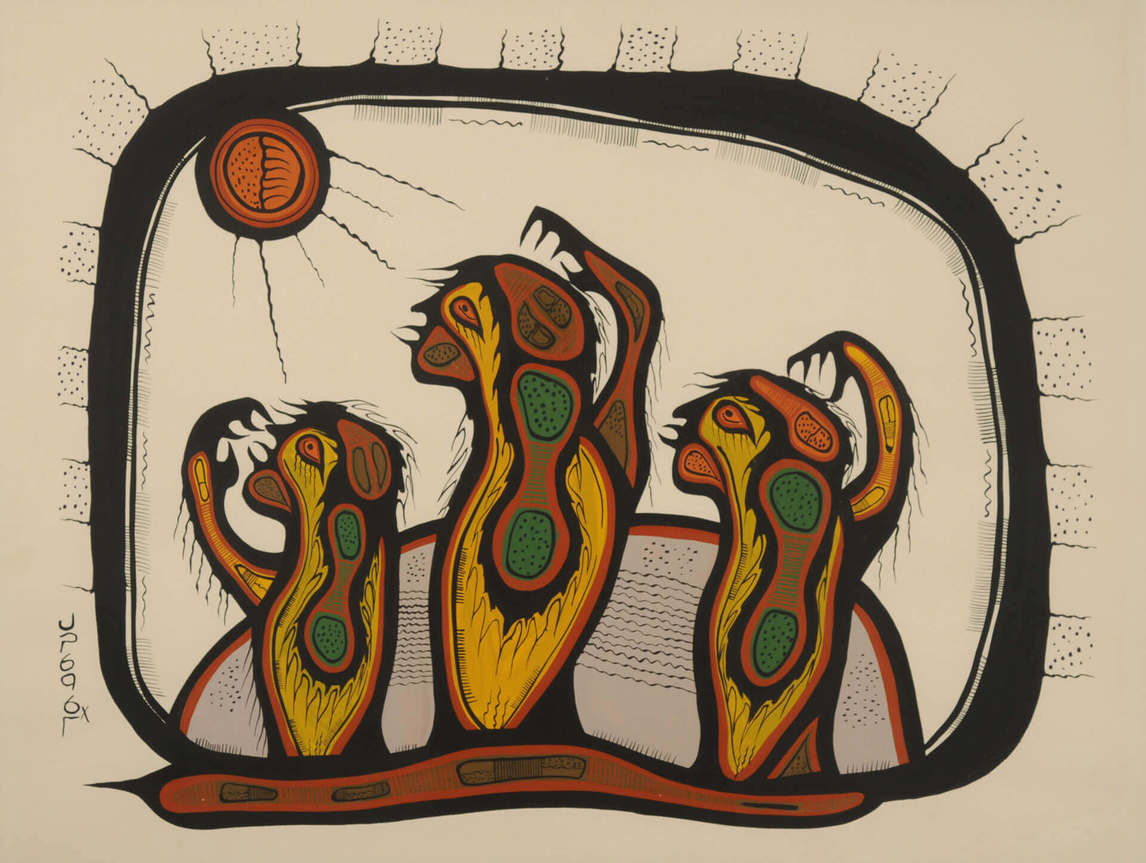

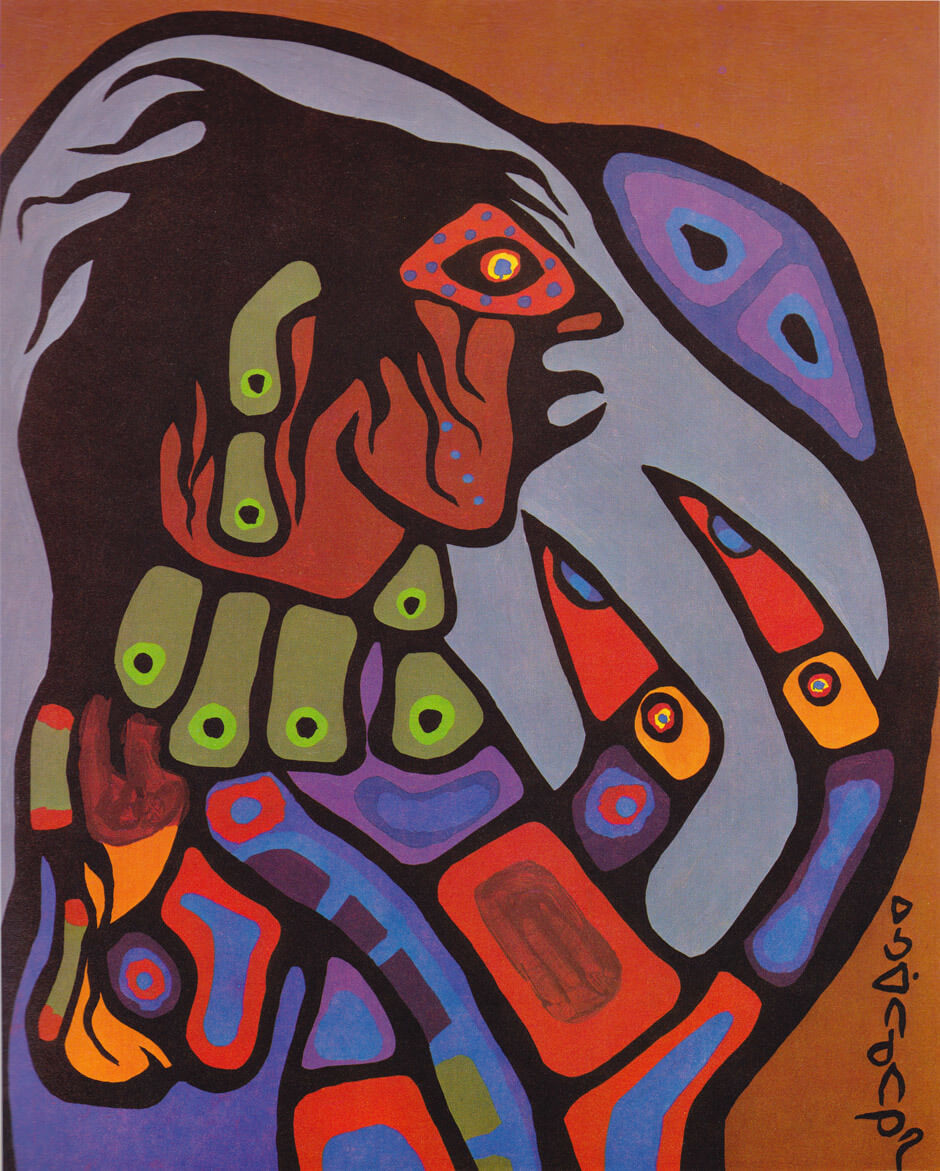

Shaped largely by Anishinaabe cultural practices and his unique approach to storytelling, Norval Morrisseau’s art style was distinctly different from what was fashionable in Eurocentric art circles. His visual vocabulary included heavy black lines that defined his subjects and divided their interior spaces, as well as the use of lines, colour, and composition that suggested relationships of interconnectedness. For example, a dramatic clash of colour and line might emphasize two opposing understandings of human relationships with the land, as in The Gift, 1975, in which Morrisseau explores colonial issues.

A new generation of artists, including Daphne Odjig (b. 1919), Carl Ray (1943–1978), Joshim Kakegamic (1952–1993), Blake Debassige (b. 1956), and Jackson Beardy (1944–1984), was inspired to experiment with Morrisseau’s style, technique, and reference to contemporary and traditional stories. This movement was described as Medicine Art or X-ray style and, collectively, the group came to be known as the Woodland School of art because many of the artists, like Morrisseau, came from northern Ontario communities. Although the name confused many people who thought the Woodland School was a physical school of art, and frustrated others who noted that it was derived from inaccurate anthropological classifications, the term stuck and continues to be used.

Norval Morrisseau and the Emergence of the Image Makers, a 1984 exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto curated by Elizabeth McLuhan and Tom Hill, charted the significance of Morrisseau’s artistic innovation. Today, artists still use his lexicon in their paintings: Anishinaabe artist Christian Chapman (b. 1975), for example, makes deliberate references to Morrisseau’s legacy of visual storytelling in his art. These devices have also migrated into popular culture on signs and websites in communities in northwestern Ontario, where they are signifiers of Indigeneity. The logo of the Assembly of First Nations includes elements of this style, with its defining black outlines, stylized eagle, and a sun symbol that conflates the four cardinal directions. Nevertheless, the work of Indigenous artists continues to be found mostly in “Native” commercial galleries across Canada rather than in mainstream art circles.

The Artist as Shaman

Shamans are considered intermediaries or messengers between the human world and the spirit worlds, and, in a global context, engage in ecstatic experience. Norval Morrisseau, too, served as an intermediary and used his art as a medium with which to illustrate spiritual pathways. Curator Greg Hill notes that the artist’s “practice of shamanism was primarily through his paintings.” Even though Morrisseau passed up the opportunity to follow his grandfather into the strict protocols of Midewiwin spiritual practice, he set out to bring shamanism into his art, as in Ojibway Shaman Figure, 1975. In Norval Morrisseau: Travels to the House of Invention, published in conjunction with Kinsman Robinson Galleries in 1997, Morrisseau describes in detail his identity as a shaman artist, explaining how he was taught to leave his body and “go to other worlds.”

Morrisseau painted a number of works that visually articulate his conflation of Anishinaabe and Eckankar spiritual cosmology and his new view of shamanism. Anishinaabe iconography such as Midewiwin hoods, sacred snakes, and the spirit-being Thunderbird, along with Eckankar symbolism, including the yellow all-seeing eyes of light, emerge in a number of works after the mid-1970s. Morrisseau assuredly paints his syncretic union of Eckankar astral travel and Anishinaabe understandings of spiritual transformation in Observations of the Astral World, 1994; the Eckankar yellow all-seeing eye of light in the headdress of the shaman on the right side of the canvas may be a self-representation.

Morrisseau’s shamanism defined him but also complicated his public identity. Throughout his career, the press often seized on stereotypical tropes found in movies, novels, and advertising to cast Morrisseau within the confining role of a “Noble Savage.” At times, Morrisseau capitalized on this reality, exploiting the clichés to his own ends. His famous 1978 tea party, in which Morrisseau played the role of shaman for a group of assembled guests, is a good example. While his performance at the event no doubt led to more sales of his art and personally touched many of his guests, his actions were ridiculed in the Globe and Mail, which noted that he “bared his loins to the sun goddess” to the “sounds of tom toms.” Morrisseau’s shaman-artist identity is complex: it could be seen to reinforce notions of authenticity promulgated by the “Noble Savage” myth, but it also intersects with his personal spiritual beliefs.

A Complicated Legacy

Norval Morrisseau challenged mainstream views of Indigenous peoples and succeeded in raising awareness and breaking down barriers. At the same time, he pioneered a new style of art that brought more Indigenous artists into mainstream galleries and is still practised today. Still, because of his struggles with substance abuse, his unconventional lifestyle, and his willingness to feed media stereotypes, Morrisseau, explains curator Gerald McMaster, became a “tragicomic artist—a role frequently reinforced by the art world.” The public’s keen interest in his unruly behaviour has tainted the legacy of his artistic achievements.

Morrisseau died in 2007 knowing he had achieved a stature few other Canadian artists have enjoyed. Yet with that success came a growing number of forgeries that have tarnished his reputation and caused wariness among collectors. Nonetheless, in 2004, late in the career of the then well-established artist, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa purchased its first Morrisseau, Observations of the Astral World, c. 1994. In the years that followed, the National Gallery acquired many additional works by Morrisseau, including Untitled (Shaman Traveller to Other Worlds for Blessings), c. 1990. Finally Morrisseau’s legacy appears to be garnering recognition, as evidenced by a growing public awareness of his artistic contributions and the increased sales of his work. His art continues to inspire and, as interest in contemporary Indigenous art grows, more and more scholars and writers like Ruth B. Phillips and Armand Ruffo are studying his life, his work, and its impact on Canadian art. Morrisseau is now taking his rightful place among the pantheon of great Canadian artists—in galleries, in academic circles, and in popular culture.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements