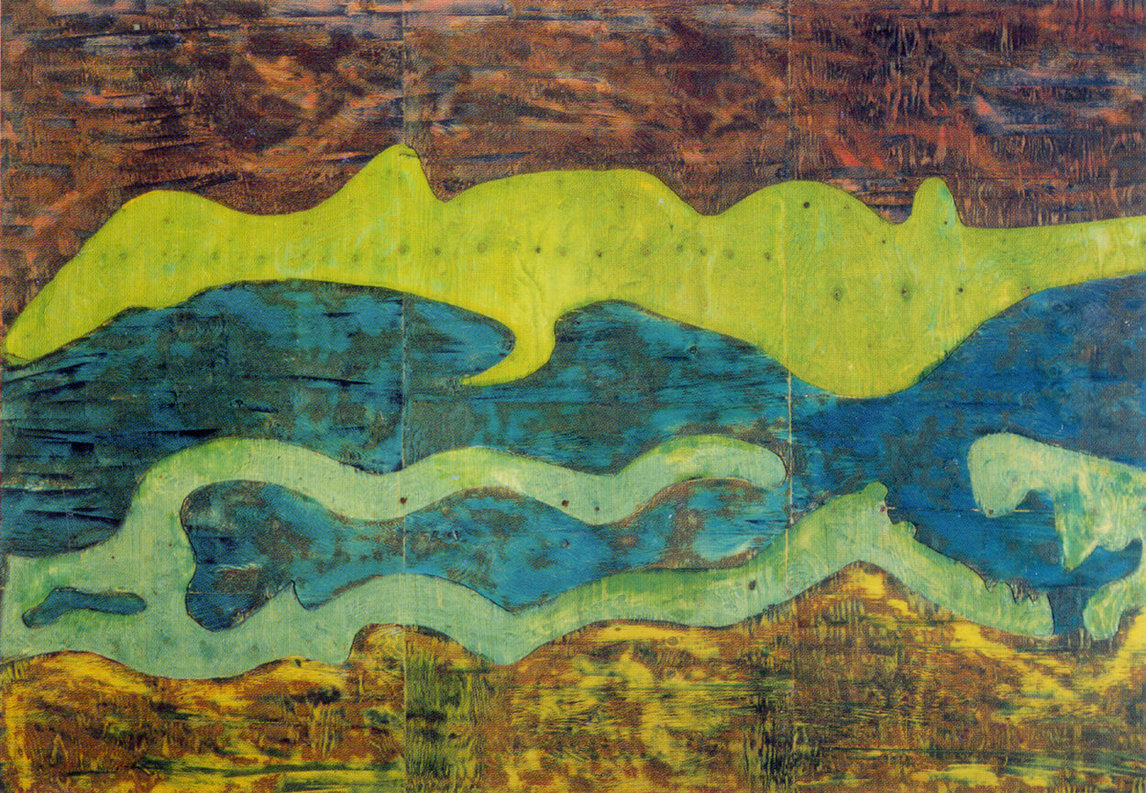

Satan’s Pit 1991

Paterson Ewen, Satan’s Pit, 1991

Coloured steel, bolts, and acrylic paint on gouged plywood, 229 x 244 cm

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Satan’s Pit is one of Paterson Ewen’s most aggressively routered plywood works. Almost entirely devoid of paint and not so much gouged as stripped away, the plywood shows an embattled surface that is torn through at its centre. The concentric circles echo the celestial bodies Ewen had painted since 1971, but here they emanate from a dark core rather than his usual light centre. Comparisons to Dante’s famous description of hell, with its different circular levels, are inevitable. It is also tempting to read the black hole literally, as a tantalizing reference to the astronomical phenomenon of popular science and culture. By the 1980s, black holes were gaining more attention, and though Ewen tended to avoid contemporary sources in his earlier works, by 1990 he appeared to be drawn to some of astronomy’s new findings. Perhaps Ewen was anticipating his own pull toward mortality or referencing the many dark moments of his past.

Satan’s Pit is part of a series of works that were the product of chance, something Ewen always seemed to embrace productively. While carving Planet Cooling, 1991, he accidentally dug too deeply with his router and made a hole through the plywood. Rather than start again, he simply worked thematically with this new feature. It is interesting to contrast the rigorous handling of the plywood in Satan’s Pit to works such as Chinese Dragons in the Milky Way or Eclipse of the Moon with Halo, both from 1997, which show little if any routing. Clearly, subject matter plays an important role in the materiality of these works.

The similarity in the forms of Sun Dogs #4, 1989, and Satan’s Pit hints at the possibility they are companion pieces: light and the absence of light; the divine as light and the satanic as darkness. Where Sun Dogs #4 is filled with colour, the lack of applied colour in Satan’s Pit suggests that without light, there is no colour—the painter’s nemesis.

In the 1996 exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, curator Matthew Teitelbaum displayed Satan’s Pit sitting horizontally on sawhorses. Accompanying the artwork was a video showing Ewen atop another piece, working its surface with a router. The juxtaposition of the gouged yet unpainted surface of Satan’s Pit and the film showing Ewen’s intensely physical routing technique was an ingenious curatorial decision. And having seen this installation at the exhibition, mixed-media artist Yechel Gagnon (b. 1973) was inspired to begin working with plywood as a support. It was the ultimate tribute to Ewen’s unique artmaking process.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements