Vimy Memorial 1921–36

Walter S. Allward, Vimy Memorial, 1921–36

Seget limestone and concrete

Parc Mémorial Canadien, Chemin des Canadiens, Vimy, France

The awe-inspiring and majestic Vimy Memorial sits on the highest point of Vimy Ridge, rising over the Douai plain in northern France, its dramatic limestone pylons visible from a great distance. Vimy marks the place where more than 10,000 Canadian soldiers were killed or wounded in one of the most decisive battles of the First World War.1 The brutal four-day conflict that began on Easter Monday, April 9, 1917, represents the first time the four divisions of the Canadian Corps fought as a unit, and marks a defining moment in the nation’s history. In capturing the ridge, Canada earned immense respect from its allies for fighting skill and bravery, while also stoking national pride at home. Allward devoted fifteen years of his life to the Vimy Memorial, creating a monument recently described by Christopher Hume as “without parallel in scope and ambition.”2 Completed in 1936, the work is both an inspired testament to the 61,000 Canadians who lost their lives during the First World War and the culmination of Allward’s work as a sculptor.

Allward later revealed that the idea for his design had been inspired by a dream, suggesting how deeply he felt in undertaking the project:

When things were at their blackest in France, during the war, I went to sleep one night after dwelling on all the muck and misery over there. My spirit was like a thing tormented… In my dream I was on a great battlefield. I saw our men going by in thousands, and being mowed down by the sickles of death, regiment after regiment, division after division. Suffering beyond endurance at the sight, I turned my eyes and found myself looking down an avenue of poplars. Suddenly through this avenue, I saw thousands marching to the aid of our armies. They were the dead. They rose in masses, filed silently by and entered the fight, to aid the living. So vivid was this impression, that when I awoke it stayed with me for months. Without the dead we were helpless. So I have tried to show, in this monument to Canada’s fallen, what we owed them and will forever owe them.3

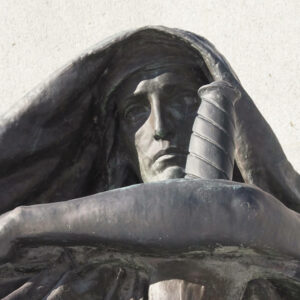

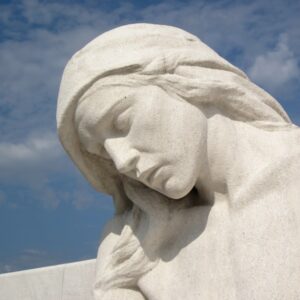

Starting in 1921, Allward drew approximately 150 sketches before arriving at his final design, which he described as “a sermon in stone against the futility of war.”4 The monument, a blend of classical and modernist elements, is on a site that is part of 290 acres of land that the French government granted to Canada to use in perpetuity as a memorial park. It features a horizontal base 236 feet long by 36 feet high, surmounted by two pylons, symbolizing Canada and France, rising 100 feet above the platform. It is adorned with twenty sculpted allegorical figures, including two groups, one at each end of an “impregnable wall of defense”, that represent breaking the sword of war and offering of sympathy to the grieving and helpless.5 Above each group is a canon covered with laurel and olive branches, symbols of peace. At the top of the front wall stands “the heroic figure of Canada brooding over the graves of her valiant dead,” echoing traditional images of the Virgin Mary in mourning.6

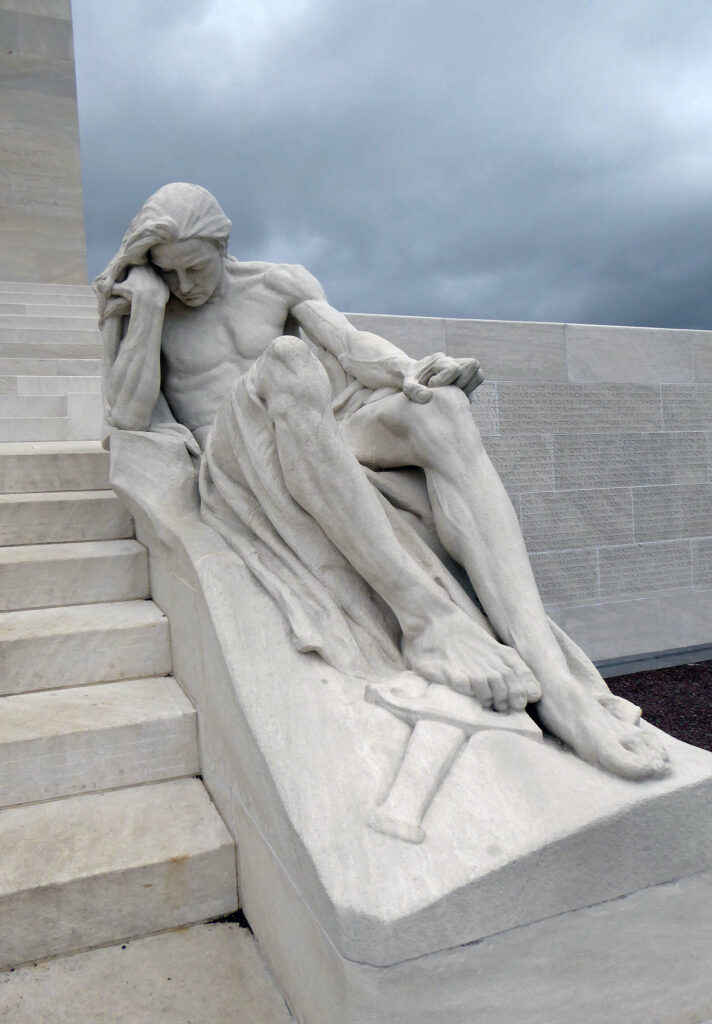

Behind this sculpture, at the base of the twin pylons, is a dying soldier, The Spirit of Sacrifice, his pose suggesting the crucified Christ. He stands next to a figure portraying The Passing of the Torch, a reference to one of the most famous poems of the First World War, “In Flanders Fields” (1915), by the Canadian Army Medical Corps officer Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae. Together, the two figures represent sacrifice and spiritual rebirth. Near the top of the pylons eight figures depict Faith, Hope, Honour, Charity, Knowledge, Justice, Truth, and, at the very top, Peace. Two reclining figures in mourning, inspired by statues Michelangelo (1475–1564) created for the Medici Tomb in Florence and symbolizing the grieving parents of dead soldiers, are positioned on each side of the stairs on the back of the monument. As with Allward’s earlier war memorials, there is no sense of triumph at Vimy, the twenty allegorical figures instead conveying loss, sorrow, and redemption.

-

Walter S. Allward, Vimy Memorial (detail of The Sympathy of the Canadians for the Helpless), 1921–36

Seget limestone and concrete

Parc Mémorial Canadien, Chemin des Canadiens, Vimy, France

-

Walter S. Allward, Vimy Memorial (detail of The Breaking of the Sword), 1921–36

Seget limestone and concrete

Parc Mémorial Canadien, Chemin des Canadiens, Vimy, France

-

Walter S. Allward, Vimy Memorial (detail of Canada Bereft), 1921–36

Seget limestone and concrete

Parc Mémorial Canadien, Chemin des Canadiens, Vimy, France

-

Walter S. Allward, Vimy Memorial (detail of the Chorus), 1921–36

Seget limestone and concrete

Parc Mémorial Canadien, Chemin des Canadiens, Vimy, France

Allward spent two years preparing detailed plans and searching for stone of the right texture and tone for the monument. More time was needed to clear the site of debris and construct the concrete foundation. The cornerstone was finally laid in September 1927. In 1930 Luigi Rigamonti (1872–1953), an Italian sculptor whom Allward had met shortly after arriving in London in 1922, began carving the sculptures from the plaster maquettes that Allward had made in his London studio and then shipped to the Vimy site. The first to be completed was Canada Bereft, now one of the most recognizable sculptures in Canadian art. Allward’s actual model for the work was a former professional dancer named Edna Moynihan, whom he had hired through an advertisement in The Stage newspaper. During his interview with her, Allward measured her shoulders, explaining that he wanted to create “a mother figure with shoulders wide enough to carry the sorrows of dead sons.”7

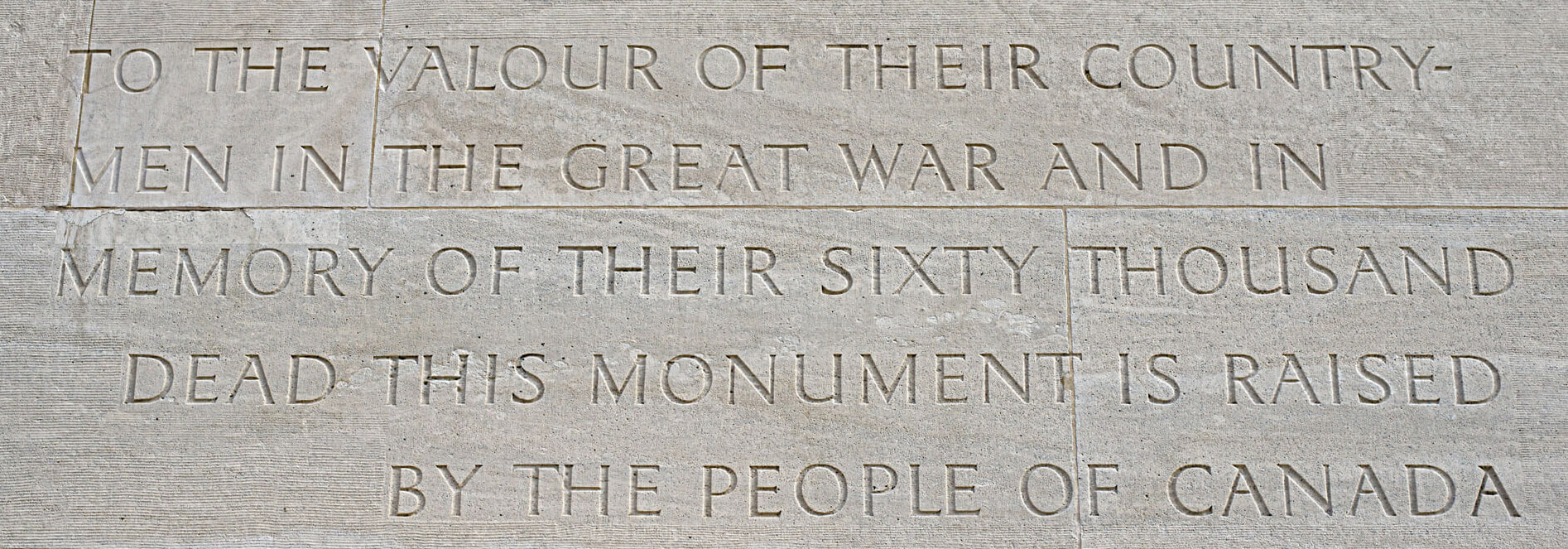

As Rigamonti supervised the carving of the figures, Allward hired the acclaimed British artist and designer Percy John Delf Smith (1882–1948) to engrave on the lower walls of the monument the names of 11,285 Canadian soldiers killed in France during the First World War whose final resting place is unknown. Smith also inscribed on the front wall the following words in French and in English: “To the valour of their countrymen in the Great War and in memory of their sixty thousand dead this monument is raised by the people of Canada / À la vaillance de ses fils pendant la Grande Guerre, et en mémoire de ses soixante mille morts, le peuple canadien a élevé ce monument.”

Allward’s perseverance in realizing his vision and his commitment to perfection were evident throughout the Vimy project. Colonel H.C. Osborne of the Imperial War Graves Commission noted at a ceremony honouring Allward, “He thought always in terms of centuries to be. Grandeur of conception, flawless construction, perfect proportions, gracious lines and glorious sculpture combine in a creation which nations will admire and which will thrill Canadians with pride in the generations that are to be.”8

Now part of the Vimy Ridge National Historic Site of Canada maintained by Veterans Affairs Canada, the monument underwent major restoration in 2005. With almost one million visitors a year, it remains one of Canada’s best-known works of public art.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements