Walter S. Allward (1874–1955) was one of the most innovative modern sculptors in Canadian history. As a young man he was quick to absorb the main tenets of the current Beaux-Arts style, but his creative drive and perseverance ultimately gave rise to extraordinary forms previously unknown in Canadian sculpture. The complex and time-consuming process of producing monumental sculptures, whether in bronze or stone, demanded a high degree of skill and patience, reflected in the various techniques he used and in the appearance of his finished works.

Defining a New Style for Canadian Sculpture

Like many leading sculptors in Canada at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, Hamilton MacCarthy (1846–1939), Louis-Philippe Hébert (1850–1917), and George W. Hill (1862–1934) among them, Allward was influenced by the teachings of the École des beaux-arts in Paris, an approach that dominated Canadian sculpture during this period. As evident in such works as Hébert’s Maisonneuve Monument, Montreal, 1895, and Hill’s Boer War Monument, Montreal, 1907, the Beaux-Arts style features a pyramidal composition, with the monument’s subject portrayed in a realistic manner and placed on a pedestal raised on a larger stone base. This compositional scheme is often supplemented with allegorical or historical figures at the base. Allward’s monuments in Queen’s Park in Toronto reflect Beaux-Arts principles, as does his South African War Memorial, 1904–11.

Although Allward’s early work, such as the John Graves Simcoe Monument, 1901–3, illustrates his mastery of the Beaux-Arts style, his mature work broke with that tradition. The shift is first evident in the Baldwin–Lafontaine Monument, 1908–14, on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, which presents two historical figures, the Honourable Robert Baldwin and Sir Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine, standing next to each other in front of a parliamentary desk on a horizontal pedestal and base. The work was inspired by the Admiral David Farragut Monument in New York City, completed in 1881 by the American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907). Similar to Saint-Gaudens, Allward uses a gently curved horizontal pedestal to bring the figures of Baldwin and Lafontaine close to eye level while also allowing viewers to move within the space of the sculpture, a feature enhanced by incorporating, as part of the pedestal, a bench for sitting.

Allward further refined this approach in the Bell Memorial, 1909–17, whose horizontal layout invites viewers to walk up a series of steps to the large central panel and into the space between two allegorical figures on blocks positioned approximately fifty feet apart at each end. The fullest expression of this compositional approach is realized in the Vimy Memorial, 1921–36, which effectively combines both horizontal and vertical elements in a design that encourages viewers to move within or around the monument itself and in close proximity to the figures.

As well as evolving beyond the Beaux-Arts approach to composition, Allward’s mature style rejects allegory in favour of symbolism. He was inspired by sculptors like Auguste Rodin (1840–1917), whose work he had first admired through reproductions and later through first-hand exposure during a trip to Europe in 1903. A central component of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Beaux-Arts sculpture, allegory is a means of presenting abstract concepts or ideals within a work but does not express emotion beyond hand gestures or through the addition of symbolic objects. The rise of Symbolism in France and Belgium, witnessed in Rodin’s exploration of expression and gesture in such works as The Burghers of Calais, 1884–95, developed in contrast to Beaux-Arts classicism.

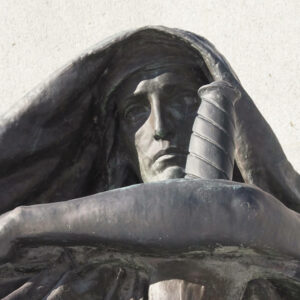

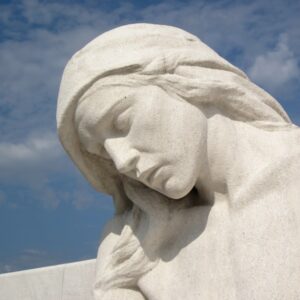

Rodin’s influence on Allward is especially evident in his sketch models for the Bank of Commerce War Memorial, 1918, and in the statues he designed for the Stratford War Memorial, 1919–22, and the Peterborough War Memorial, 1921–29. The debt to Rodin is also apparent in the twenty figures of the Vimy Memorial, where Allward similarly reveals emotion through pose, gesture, and the grouping of figures. At Vimy, as Laurie Labelle and Dennis Reid note, Allward “adopted a universal figure to convey the complex realities of war as the allegorical figure in its simplicity could no longer express the range of emotion [he] sought to convey.”

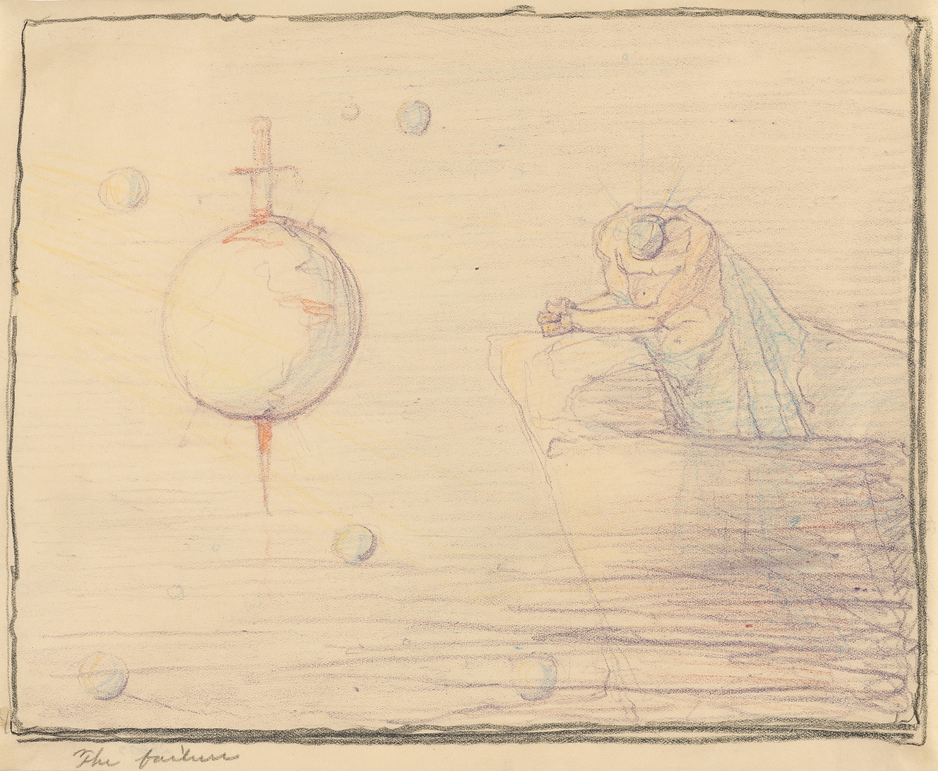

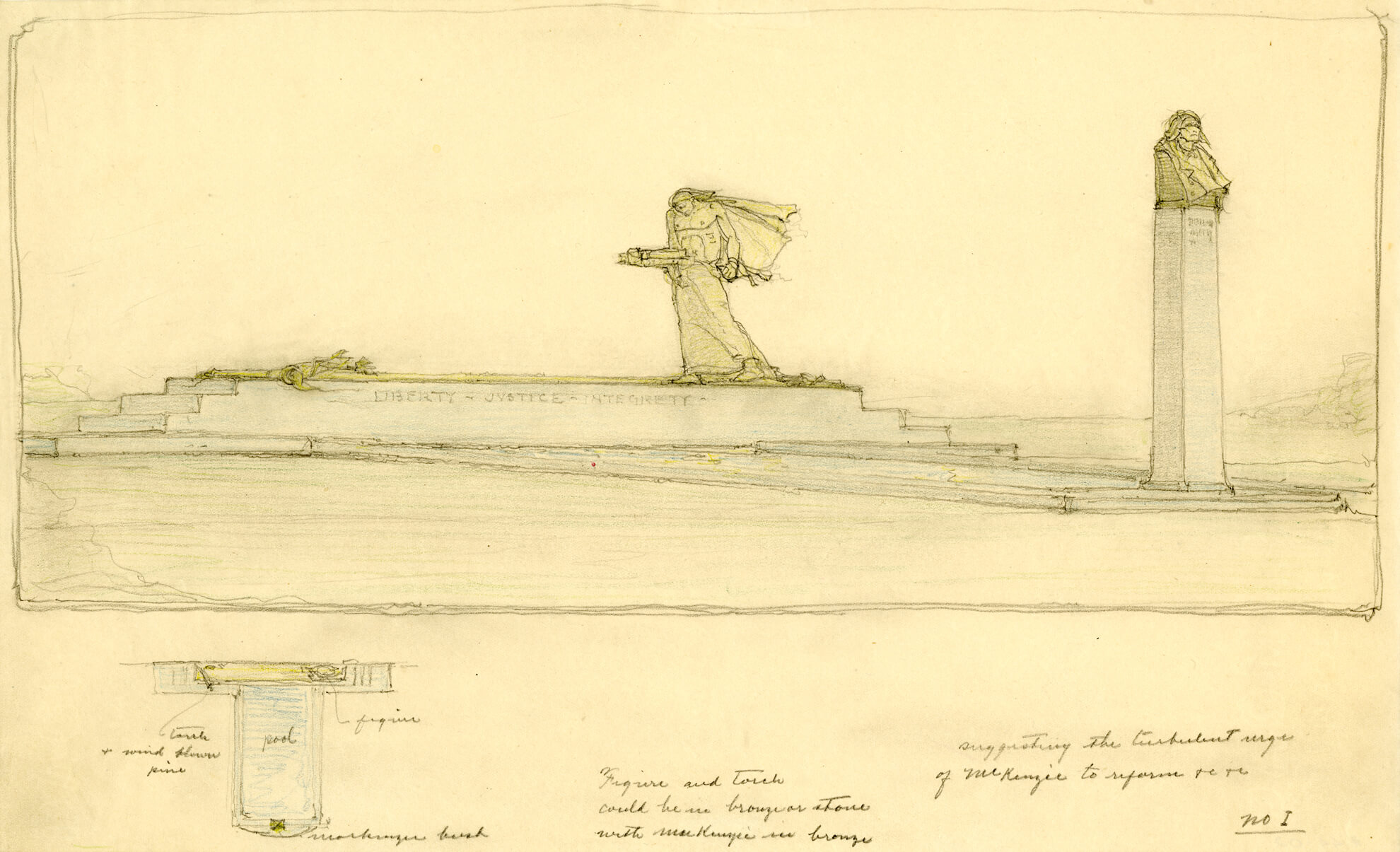

In taking this path, Allward helped to define a new direction for sculpture in Canada in which the main objective is to create emotionally expressive figures. An early indication of this approach is evident in The Old Soldier for the War of 1812 Memorial, 1903–7, where Allward emphasizes the subject’s powerful response to the suffering caused by war. The shift was recognized by his contemporaries, including fellow sculptor Emanuel Hahn (1881–1957), who in 1929 described Allward’s work as having “moved from allegory to symbolism: more introspective; concerned with an emotive and existential figure coming out of solid mass.” In his late works, the figures used in the earlier war monuments and perfected at Vimy reappear in an even more attenuated form. As Labelle and Reid indicate, Allward “created an increasingly expressive figure by exaggerating the physiognomy…to convey the concept of human struggle towards a higher ideal.” The use of visibly emotional faces and forms is repeated in Allward’s last sculpture, the William Lyon Mackenzie Memorial, 1936–40, as well as in numerous drawings, including his series of war cartoons and his sketches for the proposed Sir Frederick Banting Memorial, 1943–44, at the University of Toronto.

Designing for Committees

While many artists begin projects with complete creative freedom and no limitations, Allward almost always began a project with parameters already established. Most of his commissions were initiated by local citizens, community groups, or government agencies, who usually appointed a committee that established requirements, including the basic design specifications, the citizenship of artists allowed to participate, the submission deadline, and the project schedule. The committee would often appoint a design subcommittee to choose a sculptor and to provide comments on the artist’s work at various stages. Allward’s great talent was to create dramatic, stylistically innovative sculptures despite having to design his works within the limitations of committees’ requests.

The competition for the Baldwin–Lafontaine Monument,1908–14, on Parliament Hill, Ottawa, open to “artists resident in Canada and artists of Canadian birth residing elsewhere,” was a typical example of the submission and selection process. Advertisements placed in newspapers in Canada, Britain, and France instructed artists to present their designs as sketch models in plaster (to a uniform scale of one-and-a-half inches to the foot), along with a description. The identity of the sculptor was provided “in a sealed envelope without distinctive mark thereon” and revealed only when the committee had made their choice. In general, the number of proposals could vary significantly depending on the prestige of the project and the rules regarding who could participate. In the case of the Baldwin–Lafontaine Monument, nine proposals were submitted, each of which was examined by the committee in early 1908. After careful scrutiny, and without knowing the identity of the artist, the three members agreed that Allward’s design best fulfilled the requirements.

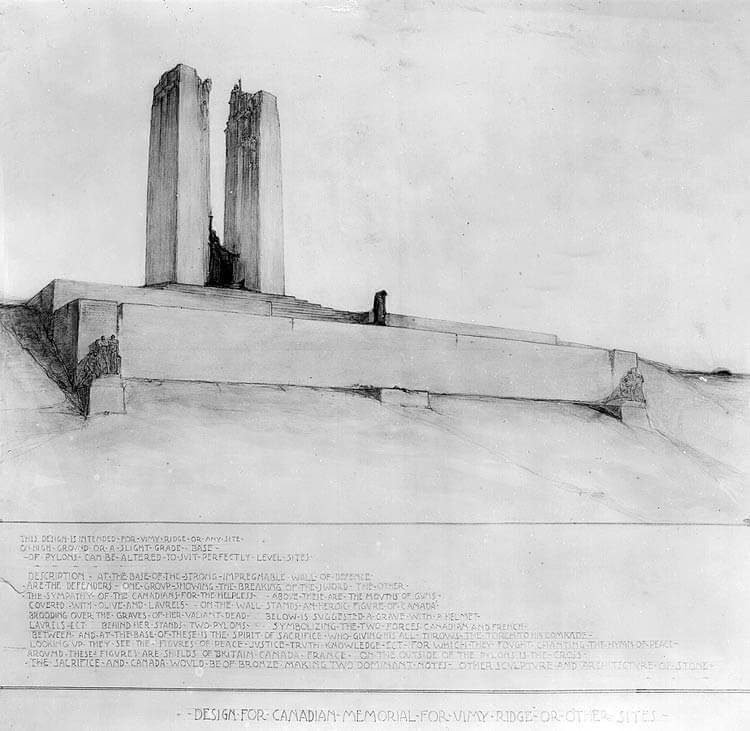

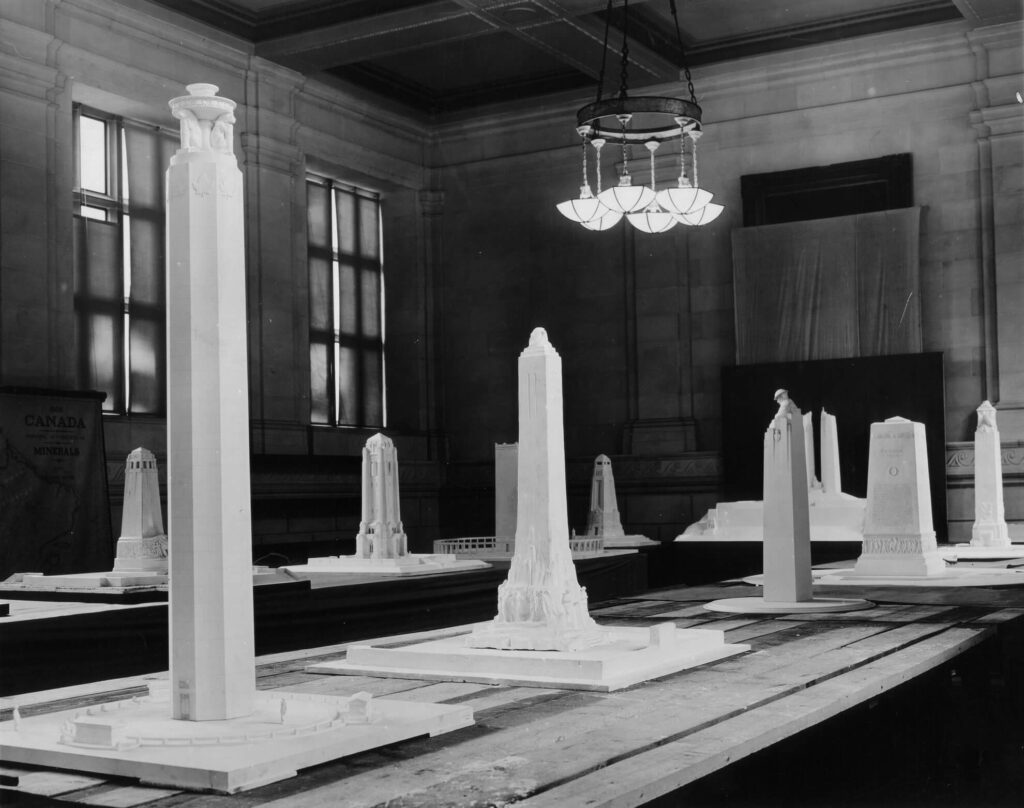

Another notable example of a prescribed competitive design process is that of the Vimy Memorial, 1921–36, Canada’s most prestigious First World War commemorative project. The competition, open to “all Canadian architects, designers, sculptors and other artists,” was announced by the Canadian Battlefields Memorials Commission (CBMC) in December 1920 and was carried out in two stages because of the large number of submissions expected. For the first round, participants were required to provide a drawing of their proposed design. The committee received sketches from 160 artists; after they were assessed, seventeen finalists, including Allward, were each paid a stipend to provide a plaster model and a written description based on the original drawing. In October 1921 a jury comprising three experts from Canada, England, and France chose Allward.

From Sketch to Plaster Model

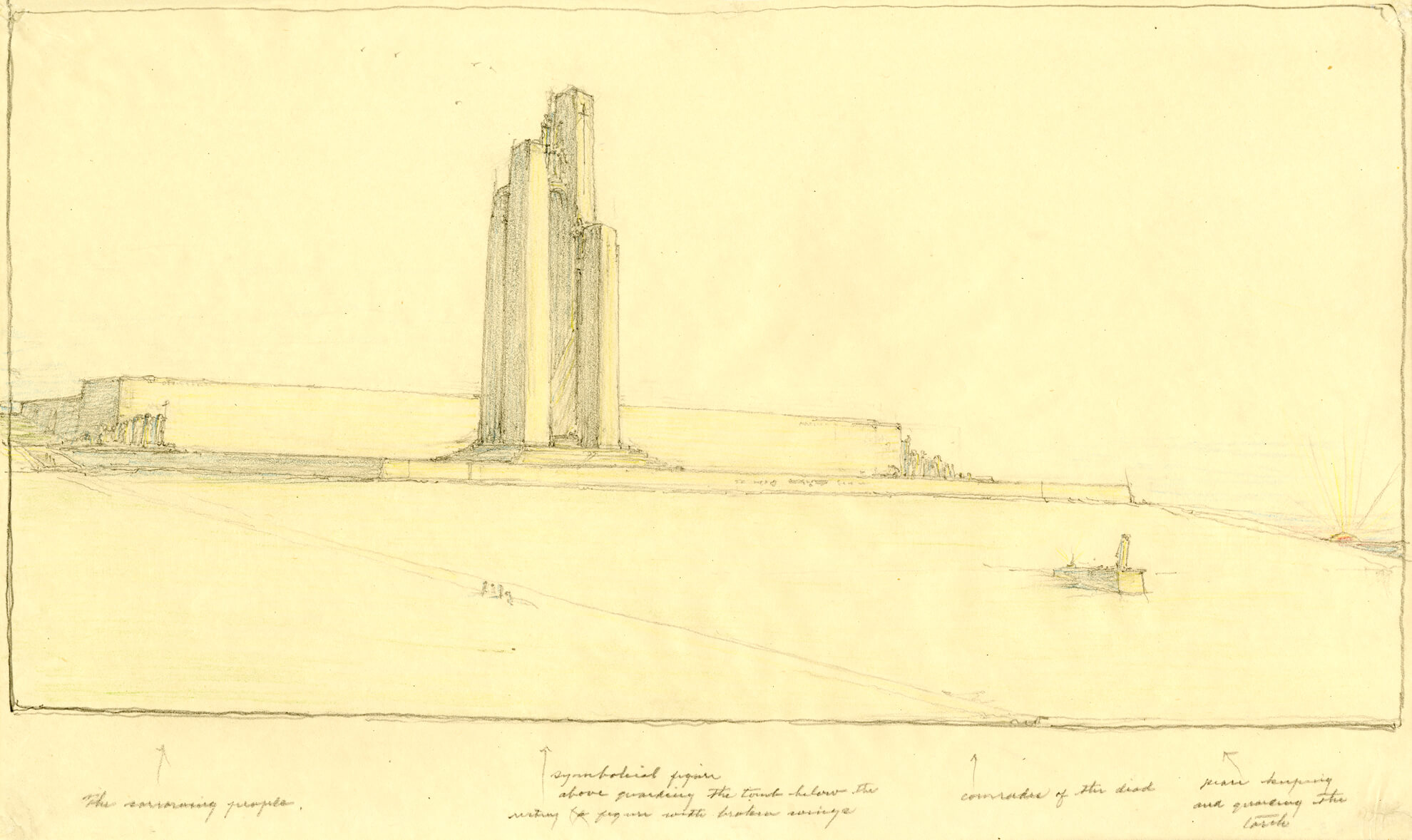

Allward first developed his ideas for a sculpture on paper and often created dozens of graphite drawings for a particular project. In developing his plan for the Vimy Memorial, 1921–36, for example, he produced more than 150 mostly graphite sketches before arriving at the final version. Among them were numerous alternative concepts, such as Alternative design for the Vimy Memorial, n.d., as well as several figure studies.

Once Allward had created a satisfactory design, he sculpted a small clay or wax sketch model, or maquette, which was usually submitted to a committee. If chosen, he would then create a more detailed half-size figure in the same material over an armature of iron or wood and chicken netting, often working from a live model and making modifications as required. From the half-size figure, Allward produced a full-size clay or wax version. Once this stage was completed, a plaster duplicate of the full-size version was cast.

The goal throughout was fidelity to the original concept, which required labour-intensive and exacting work. The critic Augustus Bridle notes, “In all these varying stages the sculptor must keep his original poetry of idea and at the same time get a fuller and freer expression of it. Lines which in the small model were undeveloped, in the larger model must come out—and much more.” Allward needed to refine his designs as he scaled them up, while preserving the concept he originally had been contracted to produce.

It was usual for a committee to monitor Allward’s work during the various stages. For the South African War Memorial, 1904–11, members of the Plans and Designs Committee made their first official visit to his studio in July 1906, when they examined the first of the full-size figures (the sculpture representing Canada) and gave their approval, subject to minor changes. The two soldiers at the base of the pylon were inspected and accepted by committee members in 1908 and 1909. After final refinements to the three figures, plaster versions were made and then sent in pieces to the Gorham Manufacturing Company in Providence, Rhode Island, for casting in bronze.

For the William Lyon Mackenzie Memorial, 1936–40, a committee headed by the architect John Lyle worked closely with Allward, consulting on his designs before visiting his studio in April 1937. As Lyle stated to his colleague Harry Orr McCurry, the work had “arrived at a stage when this small Committee should meet in Toronto to view the model that Allward has made and make a final inspection before any further work is undertaken.” Although committees ensured that a project adhered to its original objectives, they were often problematic. As Allward remarked to a journalist in 1922: “I daresay, I have been a great trial to committees. Certainly some of them have been to trial to me. But I have never lacked for sympathy from certain understanding souls, so the going has been not too hard.”

From early in his career, benefiting from his knowledge of architecture, as well as his growing reputation as one of Canada’s leading sculptors, Allward was actively involved in all aspects of a monument’s design. His contract for the Stratford War Memorial, 1919–22, for example, indicates that his fee included “the preliminary sketches, the accepted sketch model, the preparing of working drawings for the granite pedestal, and its foundation, also general supervision of the granite work, and supervision of the erection of the bronze group.” Allward also often gave advice on a monument’s location and the surrounding landscape, keenly aware that positioning and context contributed to the viewer’s experience. In his design for the King Edward VII Memorial on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, begun in 1912, he included a wall behind the figures so that the viewer’s eye would be focused on them rather than on the stone buildings behind the sculpture. For the Peterborough War Memorial, 1921–29, Allward not only approved Central Park as the best site but also designed the approach to the monument and chose the species of trees and bushes that would serve as a backdrop. His preparation for the Vimy Memorial, situated on the highest point of Vimy Ridge and facing east toward the rising sun, included modifying the ridge to improve sightlines and to create the impression that the monument arose naturally from the ground.

The process of making large monuments was labour-intensive, more so given that Allward worked slowly and meticulously. Sculptures with single figures, such as the John Graves Simcoe Monument, 1901–3, usually took two years to complete. He worked for seven years on the multi-figure South African War Memorial, from the submission of his proposal in 1904 to the installation of the final bronze sculpture in 1911. The Vimy Memorial, Allward’s most ambitious and challenging project, took many years to complete: he made his first sketches in 1921, moved to Europe to begin work on the memorial there in 1922, and completed it in 1936.

Sculptural commissions were hard to come by in Canada, being both scarce and highly competitive, and Allward generally pursued as many projects as possible. However, his increasing success meant he worked on several sculptures simultaneously. Although Allward usually worked alone, he hired studio assistants when his schedule became especially demanding. In 1908 he employed the sculptor Emanuel Hahn to help with the South African War Memorial. Hahn, who was Allward’s studio assistant until 1912, also contributed to the Baldwin–Lafontaine Monument, 1908–14, and the Bell Memorial, 1909–17. During the mid-1920s, while sculpting the figures for the Vimy Memorial in his London studio and dealing with various problems associated with the project, Allward hired the English sculptor Gilbert Bayes (1872–1953) to finish two bronze figures for the Peterborough War Memorial. As with Hahn, Bayes was assigned to sculpt full-size figures from Allward’s half-size models, before preparing plaster versions for casting.

Casting in Bronze

Most of Allward’s sculptures were cast in bronze, an alloy composed of copper, zinc, and tin, which had replaced marble as the preferred material for sculpture by the mid-nineteenth century, being less expensive as well as more durable outdoors. His sculptures were unique pieces and therefore were produced using the sand-casting method, a relatively simple and economical process that permitted the foundry to duplicate with a high degree of fidelity the intricate detail of the sculptor’s final model.

Beginning with his first professional project, the sculpture of Peace for the Northwest Rebellion Monument, 1894–96, Allward relied mainly upon foundries in the United States for bronze casting. He initially had the casting done by the Henry-Bonnard Bronze Company in New York City or by Bureau Brothers in Philadelphia. Starting with the figures for the South African War Memorial, 1904–11, Allward used the Gorham Manufacturing Company, located in Provincetown, Rhode Island, who also cast the John Sandfield Macdonald Monument, 1907–9, the Baldwin–Lafontaine Monument, 1908–14, and the Bell Memorial, 1909–17. As well as benefiting from the high level of skill provided by American foundries, Allward’s projects with these facilities gave him a first-hand look at the work of some of the leading sculptors in the United States. Daniel Chester French (1850–1931) and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, for example, used Henry-Bonnard and Bureau Brothers to cast many of their acclaimed works.

It was only in the early 1920s that a Canadian foundry, the Architectural Bronze and Iron Works, based in Toronto, acquired the equipment and developed the skill to cast large-scale bronze figures. Allward hired the company for Justice and Truth for the King Edward VII Memorial, begun 1912, and for the two statues of the Stratford War Memorial, 1919–22. The figures for the Peterborough War Memorial, 1921–29, completed in Allward’s London studio, were cast in bronze by the Thames Ditton Foundry in Surrey, England, the only time he used a company outside North America for bronze casting.

When a sculpture was ready to be cast, Allward would usually spend several days at the foundry to observe the process and supervise the finishing work, which included applying a patina, a procedure that involved heating the surface of a cast and applying solutions of salts and acids to give the work a decorative and durable finish. After a coat of wax was applied for additional protection, the bronze was shipped to its final destination.

Carving in Stone

Although most of the sculptures that Allward produced were cast in bronze, he also occasionally worked in stone, the most notable example being the Vimy Memorial, 1921–36. Regardless of the medium, Allward first developed his ideas on paper before producing a sketch model. The main advantage of stone over bronze was that the final plaster version did not require the same attention to detail. Allward entrusted that aspect of the work to the carver.

For the twenty statues of the Vimy Memorial, Allward produced life-size wax versions in his London studio at 16 Maida Vale, working from sketches based on living models. These figures were subsequently moulded to the same dimensions in plaster, and after minor refinements they were sent to the Vimy site for carving in situ from large single blocks of stone, under the direction of the master carver Luigi Rigamonti (1872–1953). In carving the stone figures, which were twice the size of the plaster statues, Rigamonti and his assistants used an instrument called a pantograph to reproduce the sculptures to the desired scale. With this device, the carvers “measured the relative depths of different parts of the plaster figures with a measuring rod. By drilling into the stone blocks placed beside the plaster carvings to depths determined by another connected measuring rod, they were able to reproduce the plaster dimensions at twice the scale.” Rigamonti and his assistants carved each figure or figure group, including those positioned at the top of the two pylons, in purpose-built temporary enclosures to allow work under all weather conditions. Six years were required to carve the monument’s twenty figures.

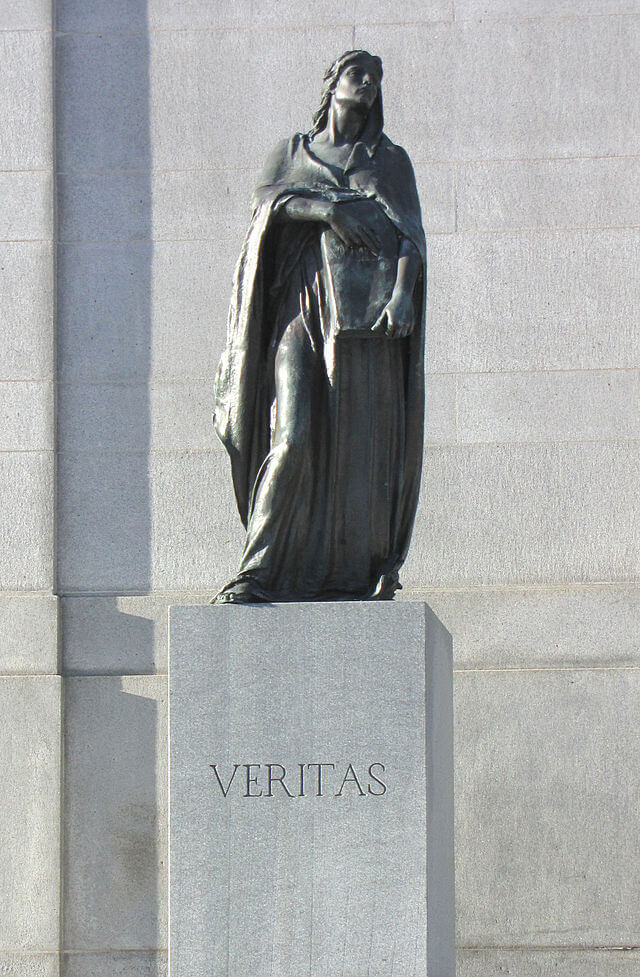

As with most sculptors of his generation, Allward preferred bronze to stone, owing to its greater durability. He chose stone for the figures of the Vimy Memorial mainly on aesthetic grounds, to give the monument a unified tone, and to a lesser extent out of fear that if cast in bronze they might be melted down for munitions in a future conflict. The only time he combined bronze and stone figures in a single monument was for the proposed King Edward VII Memorial, begun in 1912, which included three figures cast in bronze (Edward VII and the allegorical representations of Truth and Justice) and one in stone (Peace, positioned along the top of the wall behind the bronze sculptures).

Adding Inscriptions

Inscriptions were a common feature of Allward’s monuments, beginning with his earliest work in Queen’s Park, Toronto. One of his main concerns in devising inscriptions for war memorials was the presentation of the names of the deceased. For the Stratford War Memorial, 1919–22, and the Peterborough War Memorial, 1921–29, for example, the names of local men and women killed in the First World War, along with the main inscription, were carved into the blocks that formed the pedestal. Allward persuaded the committee for each memorial to accept alphabetical ordering, without distinction of rank or department of service.

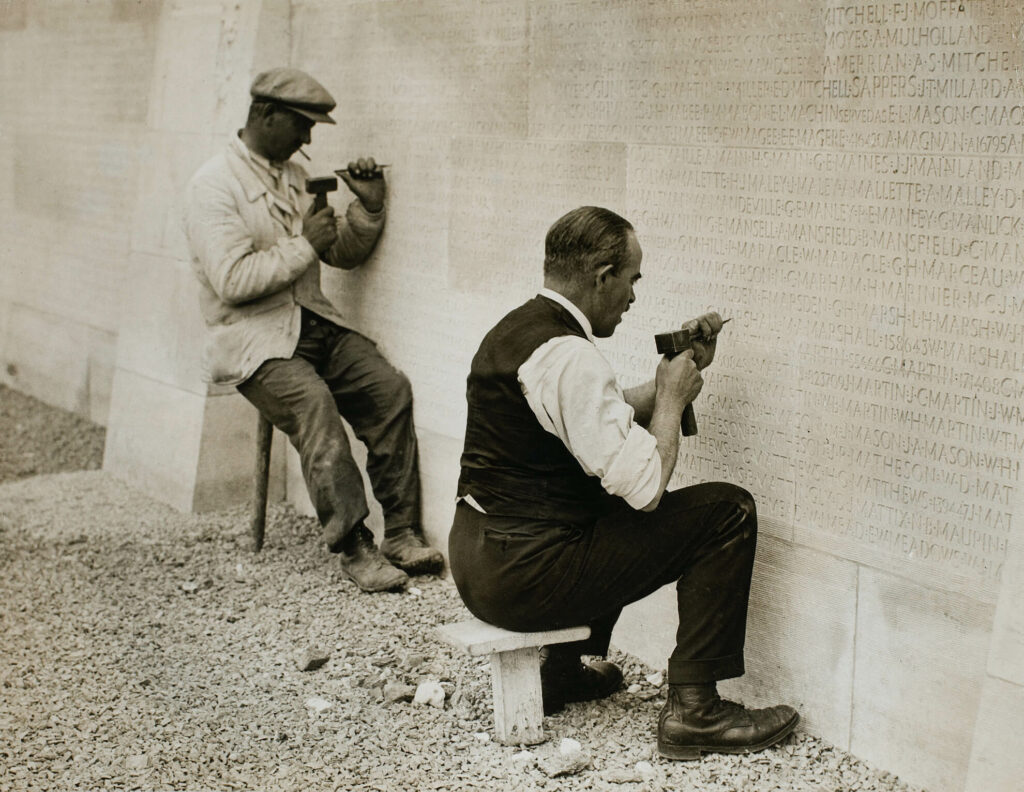

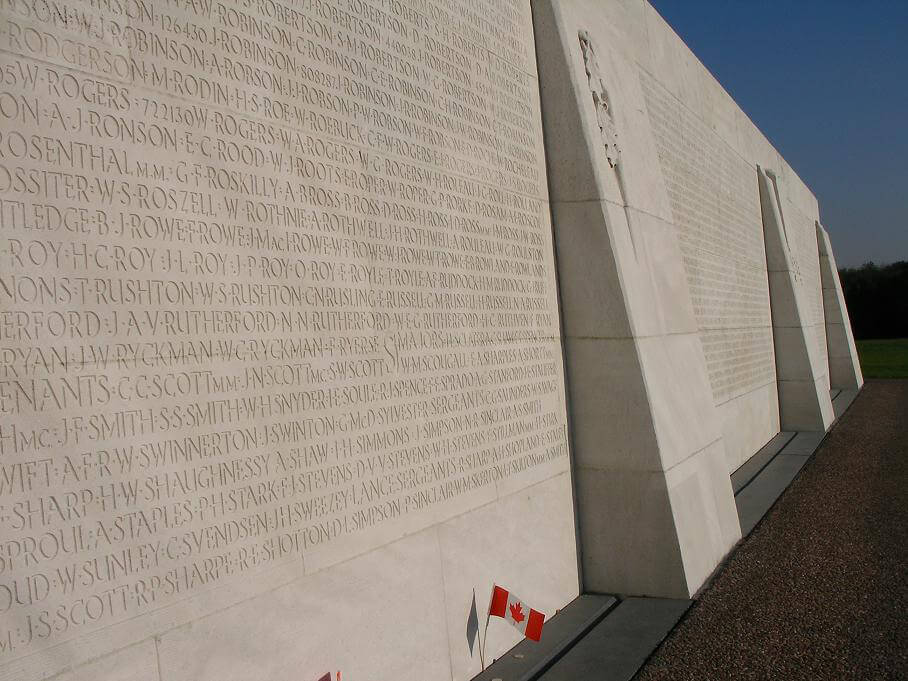

For the Vimy Memorial, 1921–36, Allward designed the lettering and chose the placement of the names of the 11,285 soldiers who were killed in France during the First World War and had no known burial place. As the names were not part of Allward’s original design, The Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) suggested that they be arranged in perpendicular columns, a format that had been adopted for the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres, Belgium, which lists the 6,983 Canadian soldiers killed in Belgium whose bodies were never found. Allward rejected that proposal, believing that it would compromise the aesthetic coherence of his design and instead suggested a horizontal layout, with names listed alphabetically from left to right across the memorial’s lower walls. By adopting this arrangement, Allward also reaffirmed the equality of those who had lost their lives. The exacting task of engraving was entrusted to the acclaimed British artist and designer Percy Delf Smith (1882–1948), whose first step was to prepare scale and full-size drawings of the names and other inscriptions. The meticulous engraving process was achieved by sandblasting through rubber templates made from the drawings. For Allward, inscriptions on his war memorials, including Vimy, were an integral part of the design, as well as a way of honouring those who had paid the ultimate price in service to Canada.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements