Notman was a proficient technician and an enthusiastic inventor of tools and techniques for his photography. He preferred the wet collodion process to the more popular daguerreotype. Best known for his development of elaborate composite photographs, Notman was generous in sharing his innovations and clearly hoped to exert his influence on the wider field of practitioners.

Wet Collodion Process

When he opened his studio, Notman worked primarily with the revolutionary, but laborious and fickle, wet collodion process perfected by Frederick Scott Archer, an Englishman, in the early 1850s. (For a wonderful demonstration of the process, watch this short video from the J. Paul Getty Museum.)

Unlike others of his generation who favoured the daguerreotype, Notman largely bypassed the process. The daguerreotype produced a small single positive image on a copper plate that had to be kept in a case away from light. Daguerreotypes originated in France and became extremely popular in North America, where they were prized for their incredible level of detail.

The collodion process entailed coating a glass plate in a chemical mixture. When the surface was tacky but not yet dry, the plate was taken to a darkroom and bathed in silver nitrate to create silver iodine. While still wet, the plate was inserted into the camera and exposed. The plate then had to be developed immediately with an acid solution and fixed. At every stage the likelihood of a decent exposure was put at risk by dust, overly dry conditions, and even a breath across the plate. Mistakes in timing or mixing were also common, and there was always the risk of chipping or cracking the plate.

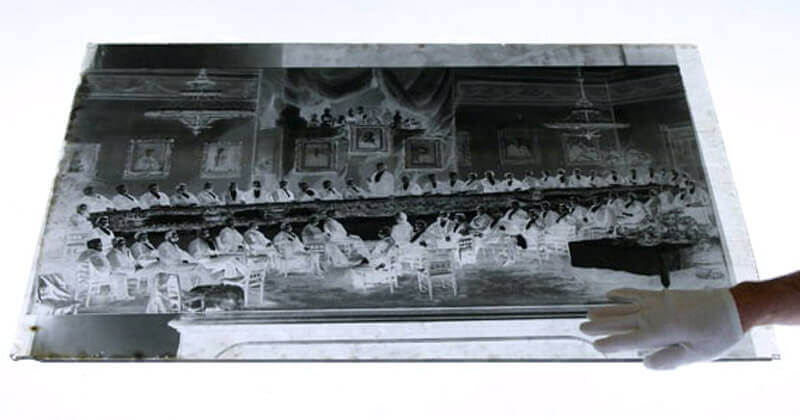

By the time he began the commission for the Grand Trunk Railway in 1858, to document the construction of the Victoria Bridge, Notman was printing unlimited copies from glass negatives. No matter what the final format, the wet collodion process produced lush and detailed images well suited to the Victorian taste for finery and ornament. It was also capable of producing larger images than the earlier processes, a capability that Notman put to excellent use in his oversized images of the Victoria Bridge construction. Glass plates were also used to produce stereoscope images. The reproducibility of the wet collodion images revolutionized Notman’s business. He was able to conceptualize each commission as an ongoing business opportunity. The second edition of the maple box, with its exquisite selection of photographs—the one on display in Notman’s studio—served to advertise prints that clients could order for themselves.

Cartes-de-Visite

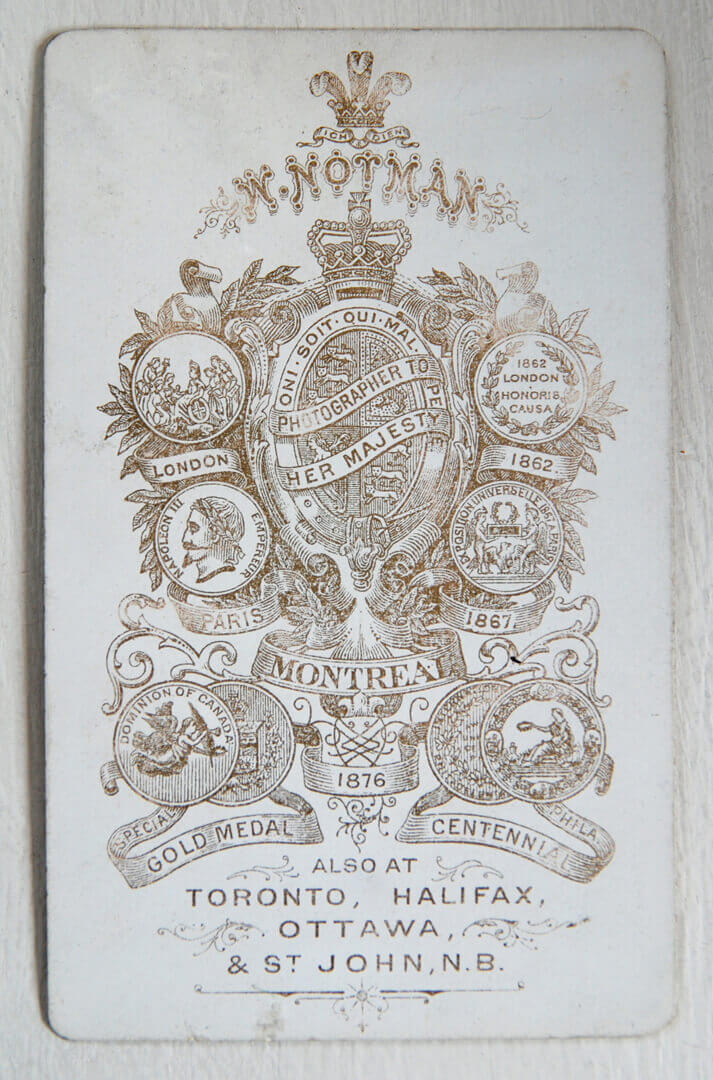

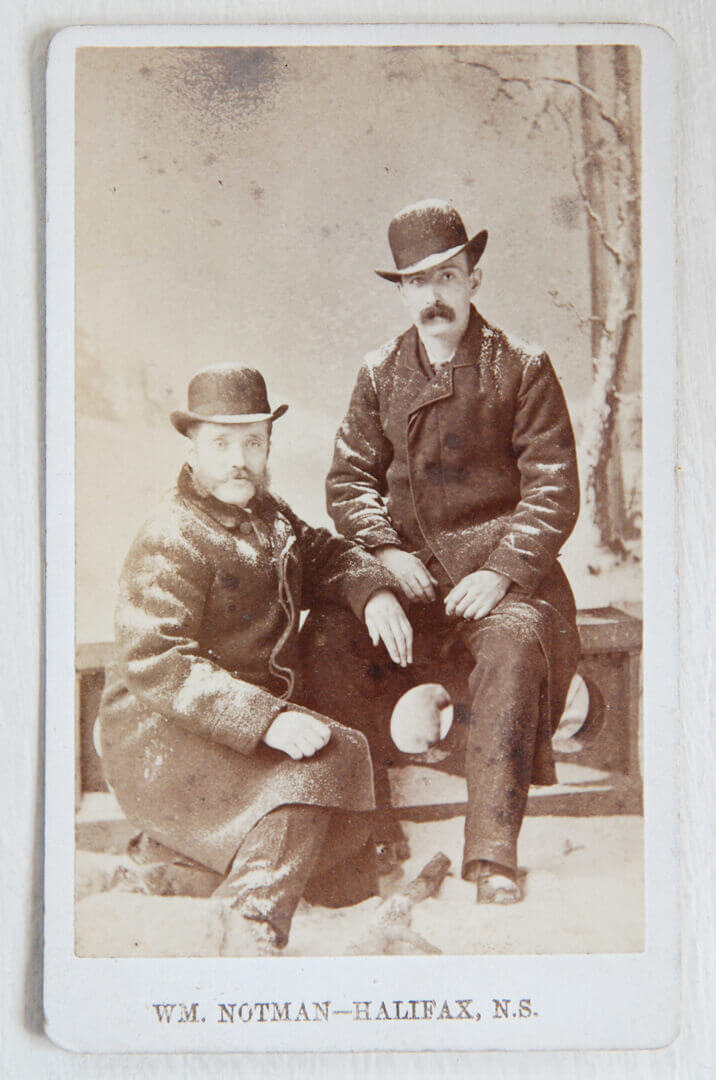

By 1860 Notman had joined the craze for the newly fashionable cartes-de-visite, with a process that cut production costs by rendering eight small negatives on the same plate and enabled prints to be made from the negative. The resulting albumen prints are small, at 2⅛ by 3½ inches (5.4 x 8.9 cm), and were mounted on a card sized 2½ by 4 inches (6.4 x 10.2 cm), ready for gifting and collecting. These small images were madly popular and fuelled a simultaneous craze for photo albums, a form of curated storage that was not possible with the metal daguerreotypes or glass ambrotypes. However, demand soon grew for a bigger photograph that would be more amenable to groups and landscapes. (The negative itself had to be larger because enlargements from negatives were difficult, though not impossible, as Notman’s famous composites attest.)

Cabinet Cards

By the mid-1860s several options appeared in the marketplace. Notman was vocal in the photographic press about the need to choose one standard size and format so that studios could continue to exchange negatives and so that equipment would also be standardized. His preference was for the cabinet card, 4¼ by 6½ inches (10.8 x 16.5 cm), and this was the format that prevailed, largely displacing the carte by the early 1870s. The cabinet card enabled photographers to adequately represent more detail and more figures in one photograph, which clearly suited Notman’s creative approach.

Carte-de-visite and cabinet card photography’s immense popularity and promise of endless reproduction created, from the earliest days, a unique challenge. To properly represent all the landscapes and portraits he had to offer for print, a businessman like Notman needed to develop careful systems for cataloguing and advertising his wares. Two sets of books kept track of the sitters and poses. These have almost all been saved, along with 200,000 negatives that now reside in the Notman archives at the McCord Museum, providing an unparalleled record of nineteenth-century culture, from photographic activity and Notman’s business to social networks, family histories, fashion, biographies, and more.

The Composite

In 1870 the occasion of a fancy dress skating carnival in Montreal’s Victoria Rink inspired Notman’s first large composite production, a technique he was credited with developing and popularizing. The process began with an overall design for the finished picture, and then individual or small group portraits were made—prints of which would eventually be cut out and pasted onto a composite negative and then printed again. Skating Carnival was made from more than three hundred individual photographs, and its creation makes evident Notman’s keen sense of marketing. Notman’s composite technique is all the more impressive when we consider that it was perfected more than a century before the development of modern photo-editing software.

Other Technical Innovation

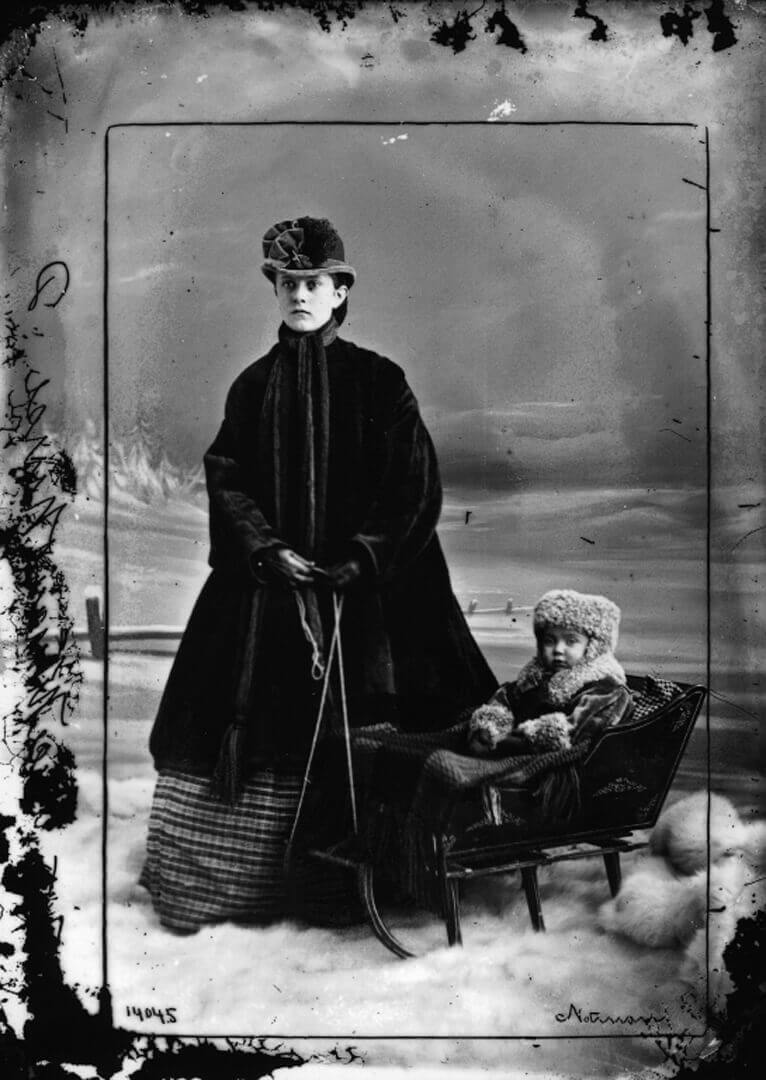

Notman’s creativity and desire to be able to do more with studio photography drove his technical innovations. The simplest of these were the techniques he developed to convincingly stage his narrative winter scenes: the polished zinc plate he created to stand in for ice, puffed lambswool for piles of snow, and paint on the glass negative to mimic the effect of falling snow. Although not directly related to photographic technology, these techniques enabled him to realize his creative photographic vision. They were of enough interest to his contemporaries to warrant description in the Philadelphia Photographer, a popular photographic magazine of the day.

Notman’s work on a functional magnesium flare also helped to stage his studio scenes, but the flare was widely applicable to various kinds of photography. Before the era of electric light, photographers universally struggled to bring enough light indoors to keep exposures brief and the image decently exposed. Notman worked with his friend and fellow Montreal photographer Alexander Henderson (1831–1913) on possible technical solutions, including a magnesium flare, that could provide a burst of light either behind or in front of the camera. The successful result of their efforts is visible as a campfire in an image from the Caribou Hunting series.

Cameras

Over the course of Notman’s long career he produced photographs of varied formats and types, including cartes-de-visite, stereographs, cabinet cards, and landscape views. Each of these required a different camera, from the two-lens apparatus used to create stereoscopic images to large-format view cameras, such as the state-of-the-art Scovill that Notman purchased from the Waterbury, Connecticut, company around 1870. More information on the type of equipment used by Notman’s studios can be found in the comprehensive sourcebook McKeown’s Price Guide to Antique & Classic Cameras or through the publications of the Photographic Historical Society of Canada.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements