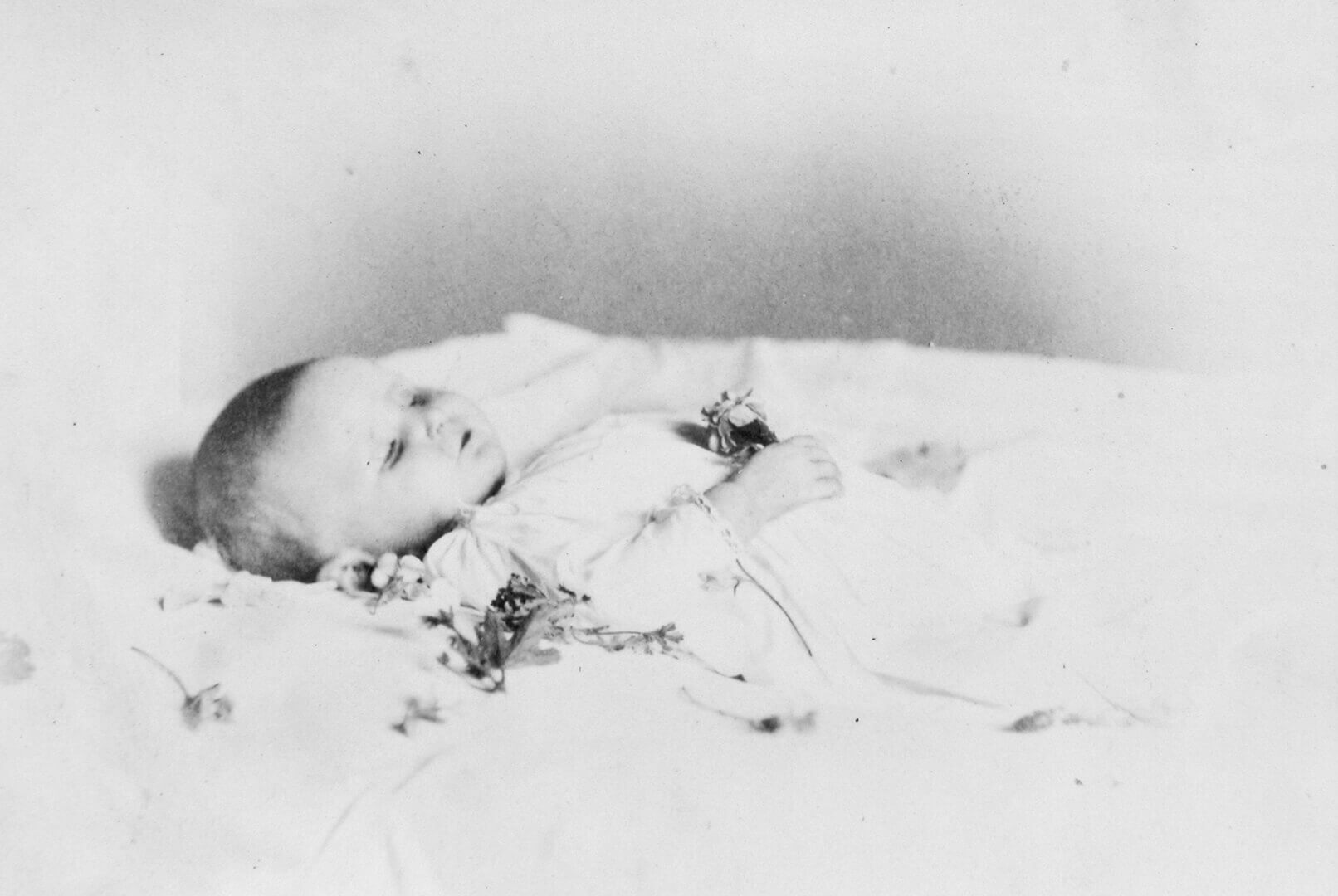

Mrs. Hillard’s Dead Baby 1868

William Notman, Mrs. Hillard’s Dead Baby, Montreal, 1868

Silver salts on paper mounted on paper, albumen process, 8.5 x 5.6 cm

McCord Museum

Of all the oddities of Victorian photography, one of the most incomprehensible to modern eyes is the post-mortem photograph. Sitting for a portrait quickly became a key social ritual for members of the upper middle class and the elite, and when a child died before a first live portrait was taken, the parents often requested a post-mortem image. The idea of posing a dead baby for a portrait may well seem macabre to us, but Victorians had a very different relationship to death and childhood mortality. Almost a third of all children born died before adulthood, and those deaths almost always took place at home. After a death, visitors were received in the family home where they could view the body, which would have been carefully arranged for those paying their respects as well as for the photographer.

Notman’s approach to child and infant post-mortem photography, at least by the mid-1860s, was carefully developed. Many American examples exist of dead children posed in close quarters with their siblings, or posed sitting up on chairs, eyes pulled open, creating an utterly haunting image. In contrast, Notman’s variations are restrained. Although some earlier examples of Notman’s work in this genre include more details of the surroundings, including the bassinet, blankets, and elaborate dress, he seems to have settled on a more simplified style by the time he photographed Mrs. Hillard’s baby.

As was fairly common, the child has been laid out with eyes closed, looking something like a doll or as though the child might just be sleeping. The background and dress are as light and simple as possible. The focus rests on the still beautiful face of the child rendered as pure and innocent as possible, an effect only enhanced by the scattering of flowers, including a stem propped in the baby’s tiny fist. If the archives are an accurate reflection, 1868 saw a sharp increase in the number of portraits the studio produced of dead children. It was the same year that Notman’s beloved first-born daughter, Fanny, died of meningitis at the age of eleven.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements