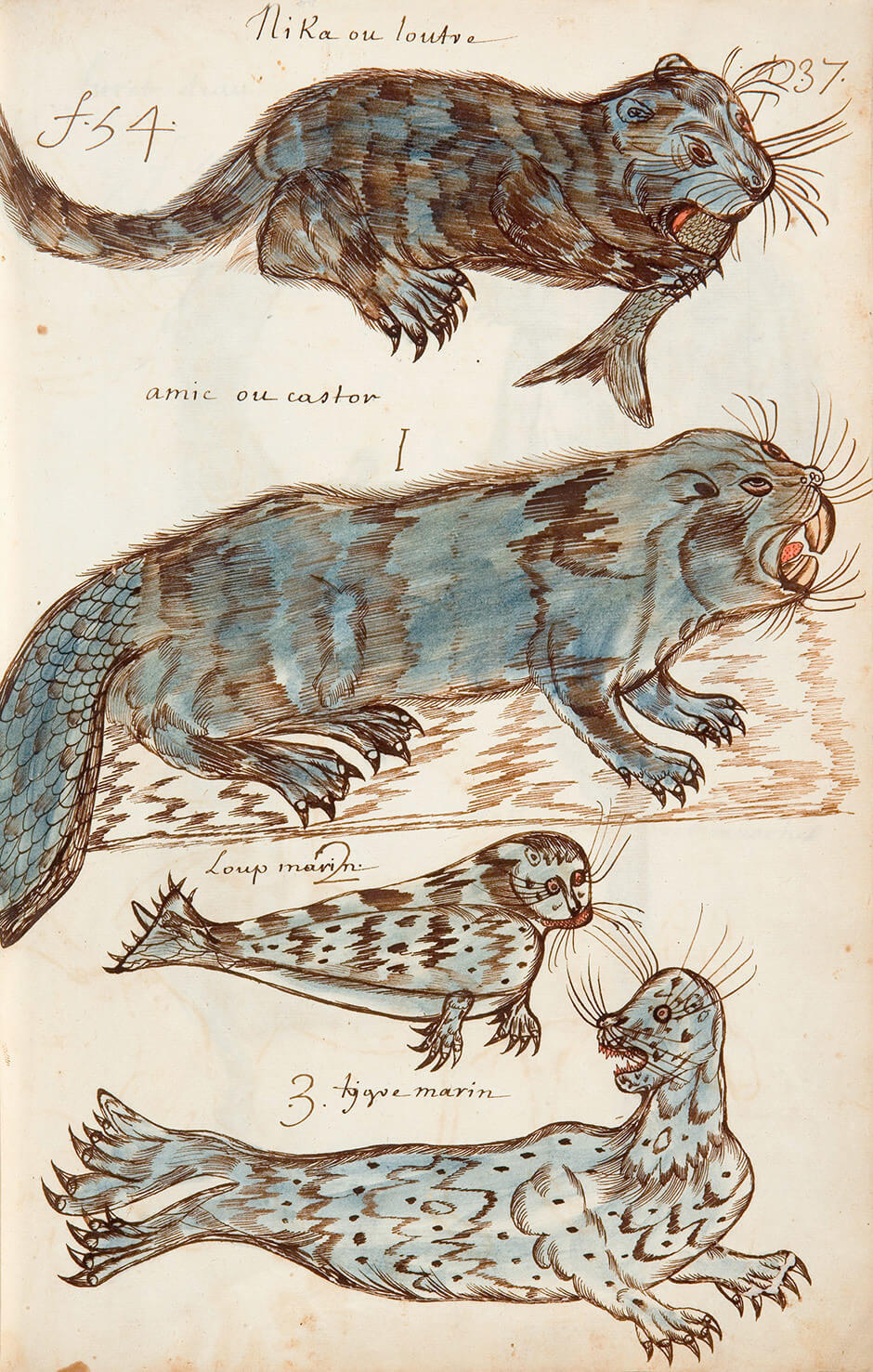

Amphibians n.d.

Louis Nicolas, Amphibians, n.d.

Ink and watercolour on paper, 33.7 x 21.6 cm

Codex Canadensis, page 37

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Illustrators in the seventeenth century rarely worked from nature. Most of the wildlife they saw up close was already dead, so the models they followed were stiff, often with their tongues hanging out. Nicolas couldn’t escape this example, and many of his drawings are also stretched out, with exposed dangling tongues—his bears, for instance, in the section on animals, and the moose. It was also common for illustrators to base their work on existing images, even if that meant using European models to depict Canadian fauna.

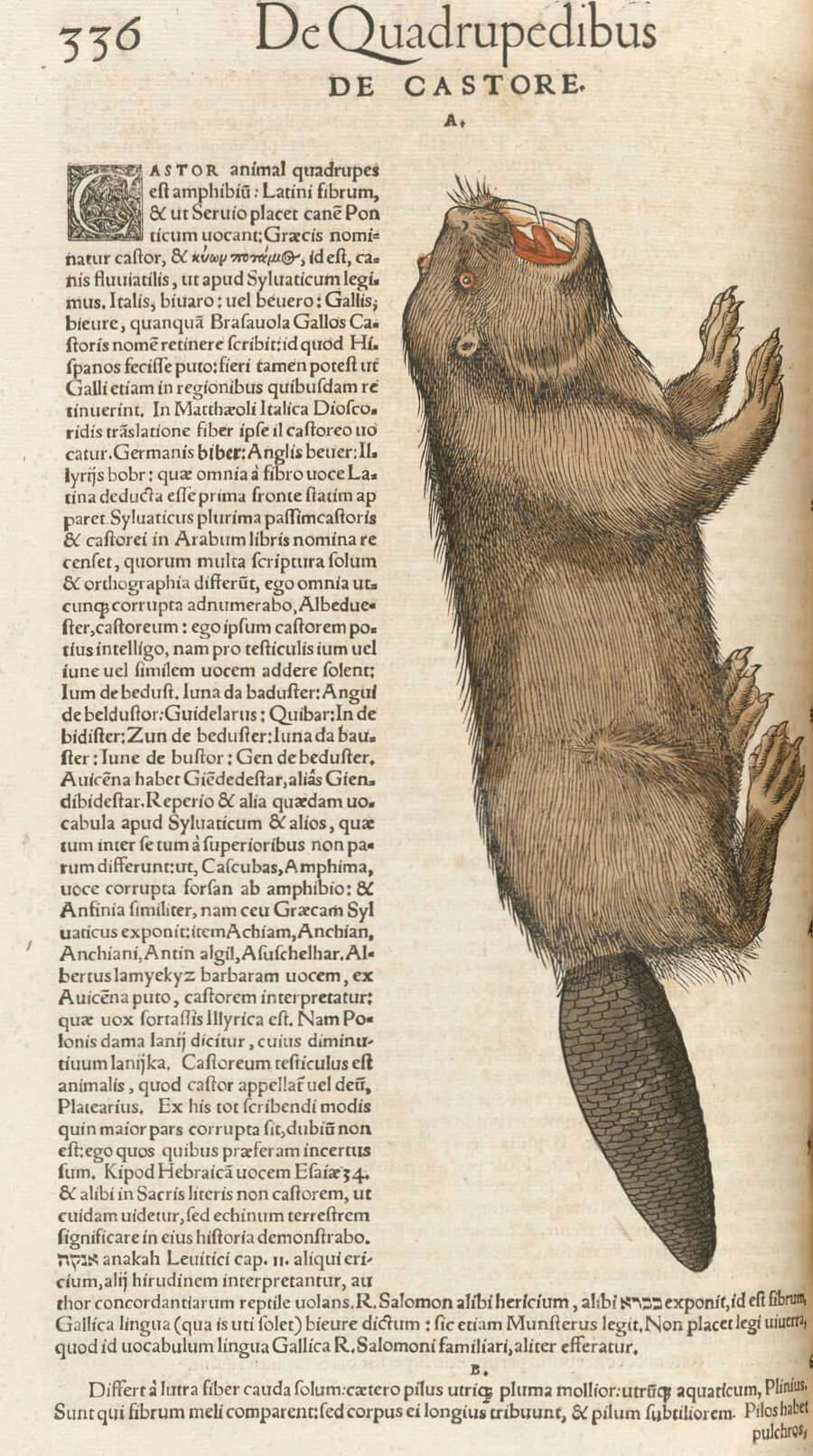

In making these four drawings that open the “amphibian” section—in descending order the otter, beaver, and seals (labelled the sea wolf and the sea tiger)—Nicolas was influenced by two published sources: The Natural History of Fishes (La Nature et la diversité des poissons) (1555) by Pierre Belon du Mans for the otter and the engravings in The History of Animals (Historiae Animalium) (1551–58, 1587) by Conrad Gessner (1516–1565). The source image he used from Gessner for the beaver has the animal standing vertically in the margin of the page, but Nicolas presents it horizontally, and posed as though it were sitting on the ground. Obviously Nicolas is breaking with tradition and trying to make his beaver look alive.

The two seals come also from Gessner. The first one was said by Gessner himself to have been copied from the sixteenth-century French naturalist and physician Guillaume Rondelet. As well, Nicolas derived the drawing of the “marine tiger” from Gessner.

All four creatures on this page are tinted in blue watercolour, to suggest that they lived in water. In addition, the outlines of their bodies are embellished with fine slanting quill strokes to capture the exact appearance of fur or hairy skin. Their whiskers, sharp teeth, and claws are carefully drawn, along with the other markings in ink on their bodies.

Naturalists at this time generally classified animals by their habitats—and Nicolas followed their example. He grouped those creatures that live on the ground as four-footed animals; those that live in the air, such as bats, as birds; and everything that lived in water, including whales, as fish. Surprisingly, Nicolas closes the section with a “mountain rat as big as a spaniel,” and classifies frogs with the fish.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements