Sea Monster Killed by the French n.d.

Louis Nicolas, Sea Monster Killed by the French (Monstre marin tue par les françois), n.d.

Ink on paper, 33.7 x 21.6 cm

Codex Canadensis, page 55

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

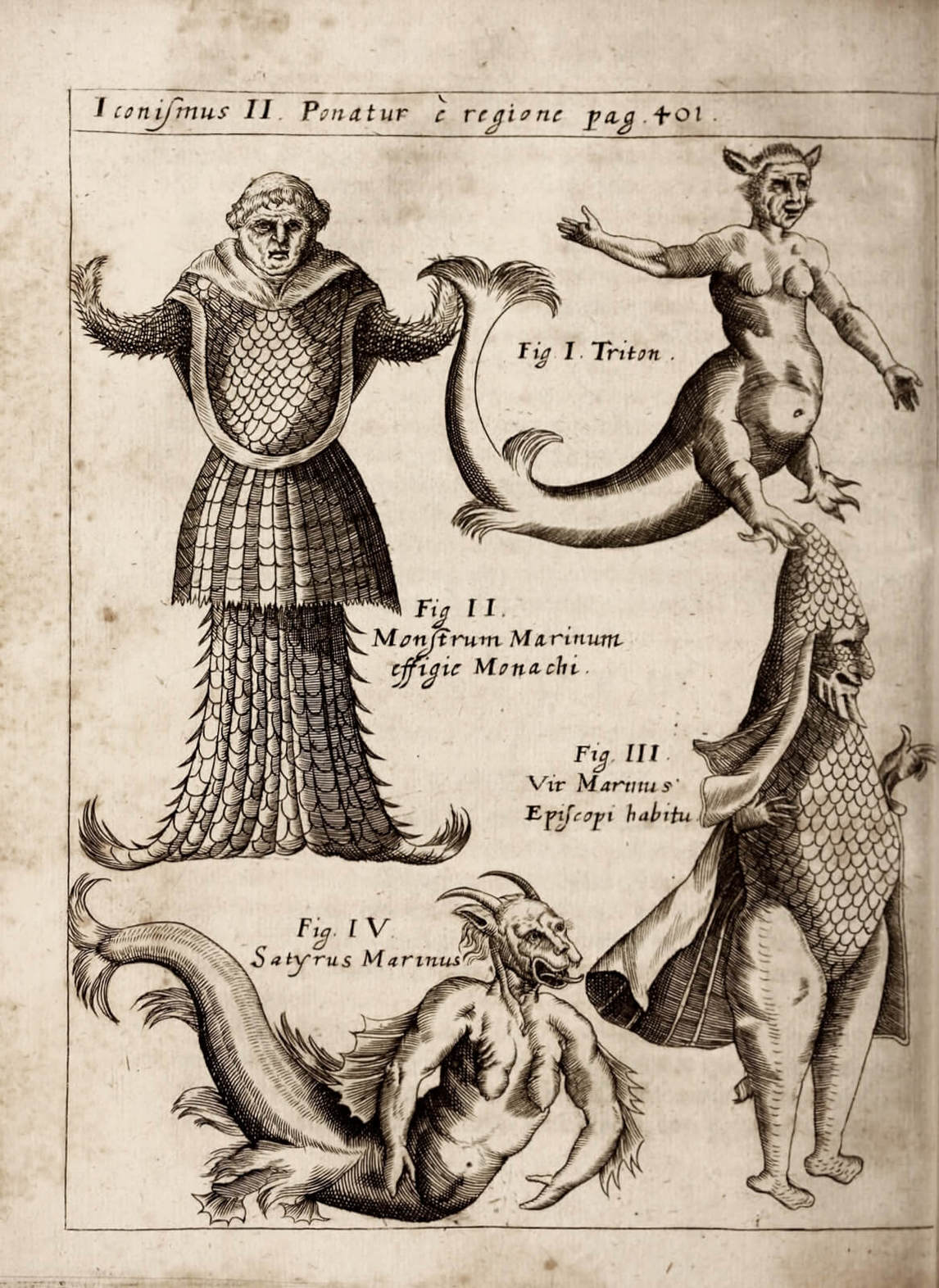

Sea monsters, living insects, and venomous, loud frogs: Nicolas chose to showcase four extraordinary creatures on this opening page of his section on fish in the Codex Canadensis. Collectively, these drawings demonstrate how he classified “fish” as any animal living in or close to the water, from frogs to whales—and he emphasized that point by positioning them all surrounded by rippling water. Like the Unicorn of the Red Sea (Licorne de La mer rouge), n.d., these four figures also present an example of Nicolas’s preference for beginning or ending each grouping of species in the Codex with examples that are in some way fantastic or miraculous.

The illustration on the top left is of a “Sea Monster killed by the French on the Richelieu River in New France”—a human-headed fish. This creature was no doubt inspired by an image reproduced by many authors in the period. Father Pierre-François Xavier de Charlevoix, a French Jesuit often distinguished as the first historian of New France, refers to a written report by an “old missionary” who claimed to have seen the sea monster “in the River of Sorel”—which we know today as the Richelieu River. Charlevoix regrets, however, that the writer did not provide a good description of what he saw. He also expressed surprise that the sea monster had not been seen by anyone else until it reached Chambly (near Montreal).

At the right of the sea monster are two small images of the “firefly” (mouche luisante), which, according to the caption, “is seen by the thousands on the evening of a fine day on the banks of the St. Lawrence River” (numbers 1 and 2). Nicolas also mentions the firefly in The Natural History of the New World (Histoire naturelle des Indes occidentales), describing it almost reverentially: “Among the remarkable things in America, I find that the firefly should not have the last rank; for on looking at it carefully, one would say that it is a living star.”

The “very poisonous tailed frog [grenouille a cue fort venimeuse],” found on the banks of the Saint Lawrence, indicates that Nicolas was unaware of the metamorphosis of the frog (number 3). It is normal for frogs to have tails before they reach their adult form, but this biological fact was not well established until the end of the eighteenth century, when Bernard Germain, Comte de Lacépède, a disciple of the French naturalist George-Louis Leclerc Buffon, recorded the frog’s metamorphosis in his General and Special History of Oviparous Quadrupeds and Snakes (Histoire générale et particulière des quadrupèdes ovipares et des serpents) (1788–89).

The “big green frog” (grosse grenouille verte) at the bottom of the page can, the caption boasts, “be heard from a distance of two leagues” when it croaks. Altogether, these four extraordinary creatures indicate that the former Jesuit, despite his learning and extensive travels, could also be a victim of his beliefs.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements