Illustration for “The First (and Last) Ottawa Street Café” 1955

Oscar Cahén, Illustration for “The First (and Last) Ottawa Street Café” by Ben Lappin, published in Maclean’s, July 9, 1955

Gouache, watercolour, pencil; 42 x 99 cm

Original in The Cahén Archives

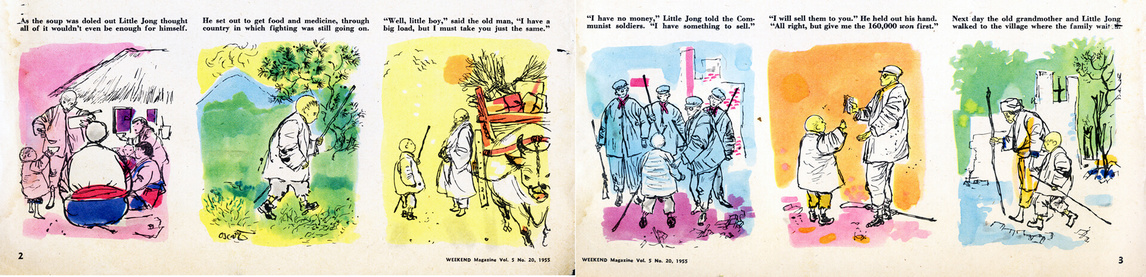

After the Second World War Canada relaxed its immigration policy, and people arrived from around the world. Magazines catered to the new readership with pieces about the Old World or about new Canadians and their tales of escape and acclimatization. Oscar Cahén was frequently chosen to illustrate such stories, as with “Little Jong is Brave as a Tiger,” a six-scene sequential narrative that documents a Korean boy’s heroism, done for Weekend Magazine.

Cahén’s elaborate street scene illustrating the memoir “The First (and Last) Ottawa Street Café” is a particularly excellent example of Cahén’s powers of visual storytelling in one frame as opposed to using a sequence of panels. Employing body language not found in the suspense-less Korean sequence, the illustration depicts the tense moment when the writer’s mother, who does not speak English, has found herself in trouble with the law over her innocent attempt to open a European-style sidewalk café. As in a theatrical scene, the dramatic event, the setting, and the characters are portrayed in such detail that one can guess what is going on without reading the text—yet be drawn into the story to find out what happens next.

Key to Cahén’s success as an illustrator was his ability to depict personality and ethnicity without resorting to stereotypes: each of the twelve people (and two cats) has a highly individualized face and expression. Cultural backgrounds are only subtly hinted at: the Jewish man’s kippah, the matron’s ankle-length skirt and embroidered apron, the gingham tablecloths. Cahén personalizes the scene, as he did in several magazine illustrations, by scrawling “Oscar loves Mimi” (his wife) on the wall. Everyday familiar touches and behaviours—the paper boat in the gutter, the potted plant on the sill, the littlest child peeping shyly from the window, the worried senior on the right—and the wide-eyed, naive optimism of the son translating for the policeman—elicit sympathy for the European immigrants navigating Ottawa’s uptight environs. Especially effective is Oscar’s strategy of showing us only the policeman’s back—his anonymity not only represents the faceless state, it focuses the viewer’s attention on the personalities of the community rather than on the officer’s judgment of them.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements