Warrior 1956

Oscar Cahén, Warrior, 1956

Oil on canvas, 201.7 x 260.6 cm

Private collection on loan to the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Oscar Cahén’s largest painting, Warrior, abandons the formalist abstract works he was concurrently developing and reaches back into his earlier repertoire concerning the human condition. In 1952 he had shown an abstract ink drawing with gold leaf titled Two Warriors and One of Their Little Machines, and before that, soldiers appeared in crucifixion scenes and illustrations. The old themes of suffering Cahén had explored in the late 1940s never left him, for in October 1956 he exhibited Grief—a couple consoling one another—rendered in black, grey, and brown oil on board.

Cahén’s personal experience with men caught in war was fraught with contradictions: his father, voluntarily mobilizing his underground anti-Nazi operation, was one kind of warrior; the thousands of average men (Nazi and Ally) conscripted to fight to their doom were another; and Christ was a warrior in a pacifist way. Cahén explored the victims of warriors (who themselves could be failed warriors) in images of prisoners, refugees, and an amputee, as in The Cripple (date unknown). In The Criminal (date unknown) the subject’s hanging head and dangling arms make him appear more pitiable than guilty, a position analogous to Cahén’s when Czech police had caught him with anti-Nazi broadcasting equipment, and later when he was deemed an “enemy alien” and interned during the Second World War.

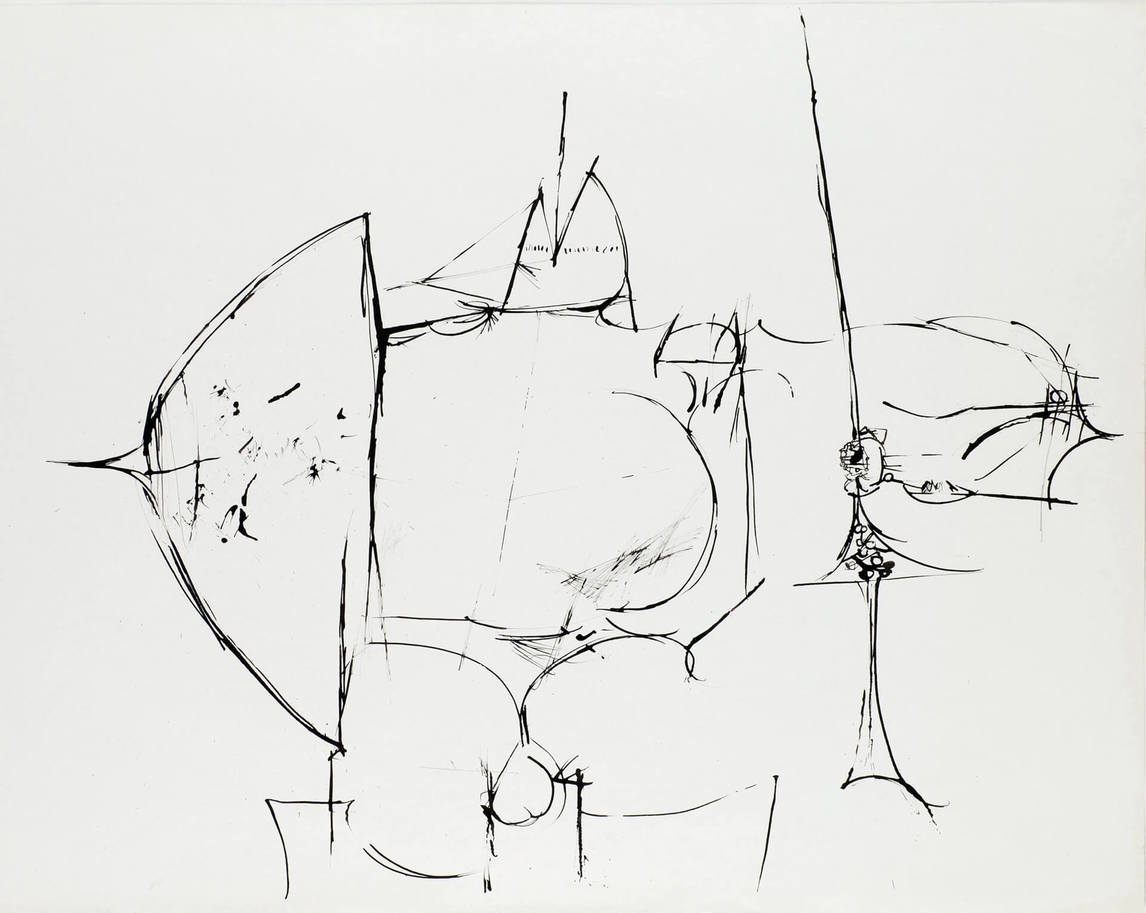

Cahén made four related one-metre-wide, black-ink line drawings. Each shows a soldier brandishing a lance with one arm, the other holding a shield. Heads take the form of medieval helmets, and massive, angular greaves protect calves. The block-like torsos lack detail, although each is given a prominent round codpiece.

Bigger than life-size, Warrior was rendered savagely in about four swift passes: the first, a line drawing in black paint on raw canvas, followed by staining of the background and colouring of the chest, head, and greaves. Then the impasto flesh-tones of a vulnerably bloated, naked torso were laid in, a penis-less scrotum where the codpiece used to be. The powerful lance-wielding arms found in the drawings are now puny weak things—like the arm of the figure in The Cripple—holding only a knife in an upright ceremonial way, as the King does on a playing card. The shield oppressively squashes the figure’s shoulder, with an effeminate pale pink field crowding in from the left.

This castrated figure in Warrior, its head now shattered as if by an explosion, is a testament to the victimhood of “warriors” (conscripted soldiers) forced to participate in conflicts not of their making. With the Second World War, the Korean War, and the Cold War so fresh, Warrior functions as an archetype as expressive of the period as any abstract painting. Cahén’s friends Walter Yarwood (1917–1996) and Harold Town (1924–1990) hung Warrior in pride of place on the title wall of the Oscar Cahén Memorial Exhibition at the Art Gallery of Toronto in 1959.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements