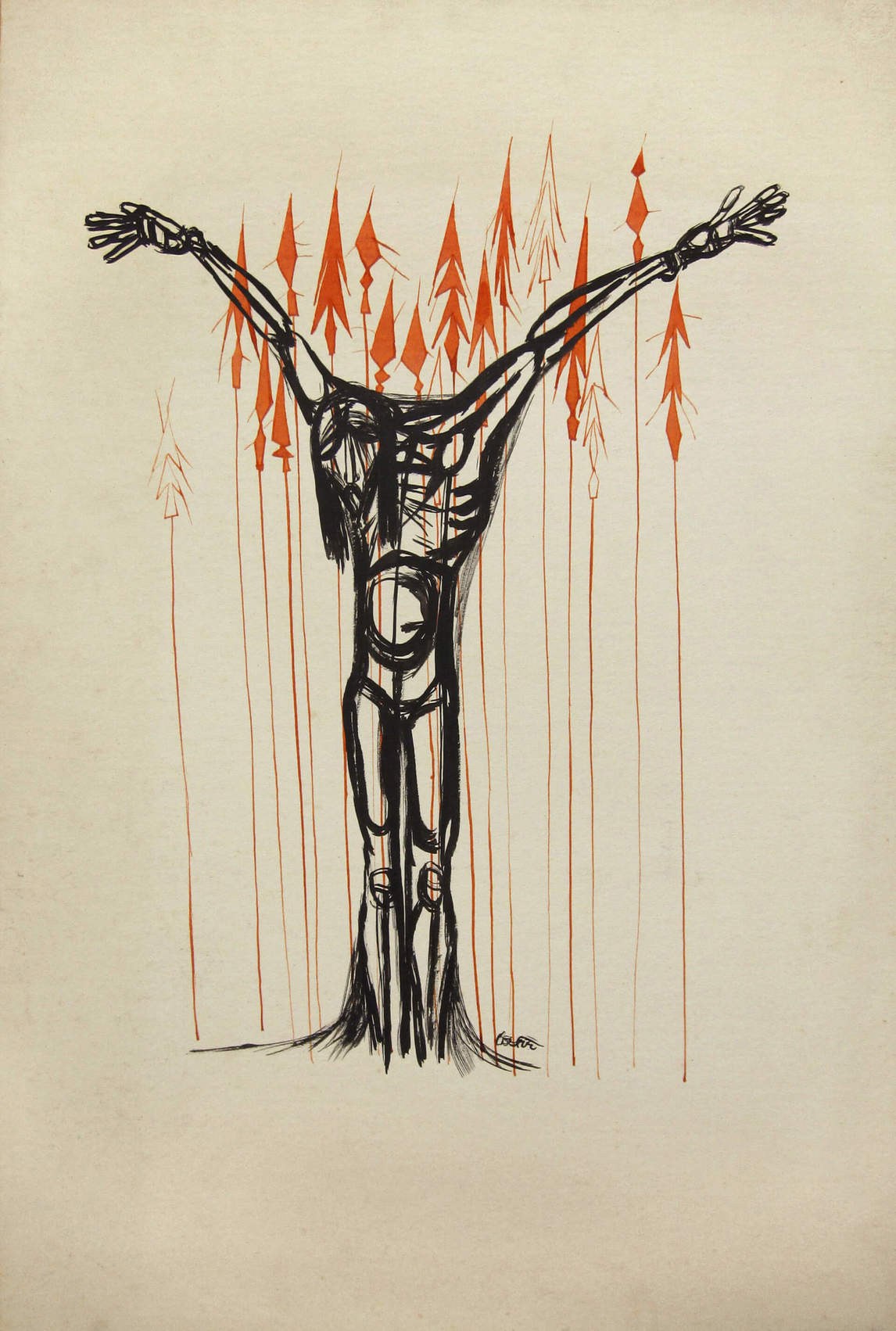

The Adoration 1949

Oscar Cahén, The Adoration, 1949

Oil on Masonite, 122 x 133 cm

Private collection

“My ambition is to show people through my work that the fundamental thing is to have faith,” said Cahén. The Adoration, first shown at the Exhibition of Contemporary Canadian Arts, 1950, and marked “Not for Sale,” was Oscar Cahén’s most ambitious work made prior to his turn to abstract painting. It depicts a traditional baby Jesus attended by Mary, Magi, and animals (and some untraditional others, such as the foreground figure bearing a lantern). However, the ethnically half-Jewish Cahén’s actual religious identity remains enigmatic. A friend recalled, “He wished he could believe in God because he wanted so much to know the peace from believing. He made a thorough study of almost every religion in the world and had the uncomfortable habit of suddenly saying, ‘Tell me, why do you believe in God?’”

Later, Cahén was to say his abstract paintings were in part a search for faith; perhaps figuration could not sufficiently address his spiritual questions. We might therefore think of The Adoration and other works with Christian subjects as allegories of universal themes rather than worshipful biblical illustrations. The prominent hanukkiyah (nine-candle menorah used during Hanukkah) in the lower left suggests that, as in the paintings of crucifixions by Marc Chagall (1887–1985), Cahén’s depictions of Jesus’s suffering might function as oblique comments on the persecution of Jews in general.

The Adoration brings Cahén’s interest in the work of Georges Rouault (1871–1958) and Gothic-period German art together with Cubism. The planes and edges of The Adoration’s figures are hidden and revealed by a mosaic of interlocking, angular shapes. Bright colours, more than narrative, direct the viewer’s eye from the yellow Star of Bethlehem to the picture’s focal point, Jesus in Mary’s hands. But the focal point is overwhelmed by the blinding whiteness of Mary’s near-rectangular apron, signifying her purity. The resulting surface pattern and visual dominance of the relatively secondary status of the apron to the story anticipates Cahén’s impending exploration of abstraction rather than illustration.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements